444

The art of patience: what happens if you look at the picture for three hours

© Jan Fabre

Harvard Professor of history of art and architecture Jennifer Roberts makes his audience at least three hours to explore the painting in the Museum or archive before you start searching information on the Internet or sources. She wrote statuo strategic patience to Harvard Magazine, from which the T&P moved the most important thing.

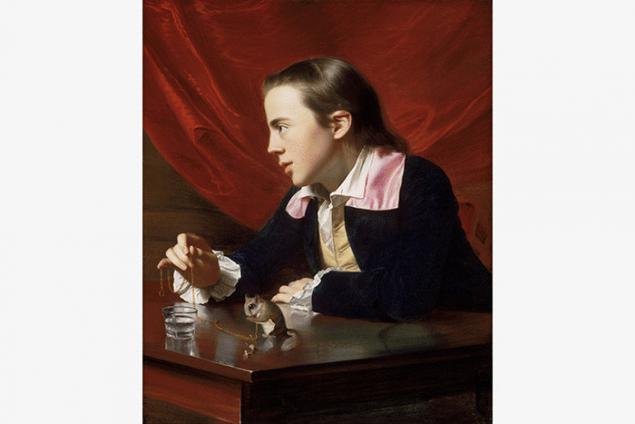

In my course of art history each student must write a detailed research about one of the paintings of their choice. And the first thing I require them to do while training is to spend a painfully long time, just staring at the object. For example, a student wanted to study the work, widely known as the "Boy with a squirrel", written in Boston in 1765, the young artist John Singleton Purchase. Before you begin reading sources and web search, a student has to go to the Museum of fine arts, where the painting, and to hold before him a full three hours, recording their developing at this time, arguments, questions, and assumptions. It is particularly important to be in the Museum or archive that isolate the student from his usual environment and potential irritants.

At first students resist such corrective exercise. How can three hours of wasted time cost of the information that will eventually be able to count with a small canvas? Isn't that a lot of reflection about a single artwork? But at the end of this experience, the students told me how they were shocked by the effect, which was revealed to them in the process... If you looked at the picture, doesn't mean you saw her — that teaches students this exercise. If something is accessible to sight, does not mean that it is available to consciousness. Access is not yet a study. Time and strategic thinking to transform access to learning.

Patience can be an extremely effective strategy. Intentional delay should be one of the primary skills that should be inculcated to students. The idea that patient work skills, of course, already very well known, but I think it's important for us to look deeper into this process. Patience is quite difficult to teach, and to instill the understanding of its importance. It sounds unreasonable traditional and nostalgic. But I would argue that once the flow of time around us has changed, and patience moved away from its original purpose. The virtue of patience initially consisted of restraint and obedience, self-preparation for the necessary pending changes. But now that we are not so exposed to the forced waiting, patience will provide us with a useful cognitive tool. If before patience was derived from a lack of influence on the situation, now it is a form of control over the pace of modern life, which otherwise begins to control us. More patience does not mean weakness. On the contrary, perhaps it is now our strength.Read the article by Jennifer Roberts on strategic patience on the website of Harvard Magazine.

Source: theoryandpractice.ru