2848

You and your work *

Long material. Reading time - about 40 minutes. I> sup>

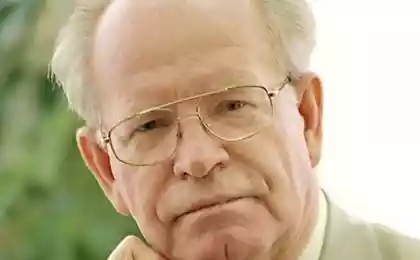

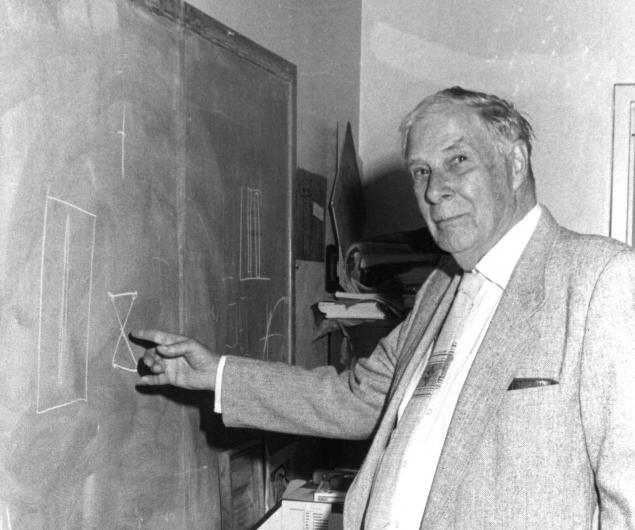

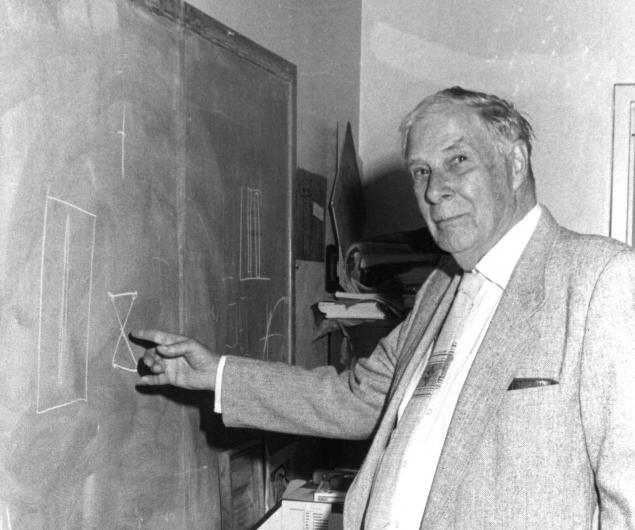

Dr. Richard Hamming, professor of marine School in Monterey, California, and a retired scientist Bell Labs, read the March 7, 1986 a very interesting and stimulating lecture on "You and your research" crowded audience of about 200 employees and guests Bellcore at a seminar in a series of colloquia at Bell Communications Research. This lecture describes the observations in the Hamming part of the question, "Why are so few scientists make significant contributions to science and so many are forgotten in the long run?". During his more than forty-year career, thirty years that have passed in the Bell Laboratories, he made a number of direct observations, scientists asked very pointed questions about what, how, where, why they were doing and what they were doing, studied the lives of great scientists and great achievements, and led introspection and studied the theory of creativity. This lecture about what he learned about the properties of individual scientists, their abilities, traits, work habits, attitude and philosophy.

Presentation of Dr. Richard Hamming h4>

Lecture: "You and your research," Dr. Richard Hamming h4>

Dr. Richard Hamming, professor of marine School in Monterey, California, and a retired scientist Bell Labs, read the March 7, 1986 a very interesting and stimulating lecture on "You and your research" crowded audience of about 200 employees and guests Bellcore at a seminar in a series of colloquia at Bell Communications Research. This lecture describes the observations in the Hamming part of the question, "Why are so few scientists make significant contributions to science and so many are forgotten in the long run?". During his more than forty-year career, thirty years that have passed in the Bell Laboratories, he made a number of direct observations, scientists asked very pointed questions about what, how, where, why they were doing and what they were doing, studied the lives of great scientists and great achievements, and led introspection and studied the theory of creativity. This lecture about what he learned about the properties of individual scientists, their abilities, traits, work habits, attitude and philosophy.