534

We are governed by parasites. Literally

We are governed by parasites. And it's not a figure of speech, not an attempt to portray a beautiful metaphor. All literally. Parasites have created our society in the form in which we know it. Our relationship with each other – love, hate, friendship, enmity, xenophobia – all these ways of protection. Parasites gave us religion, the state established the social order. Depend on them in our lives a lot.

The FACT

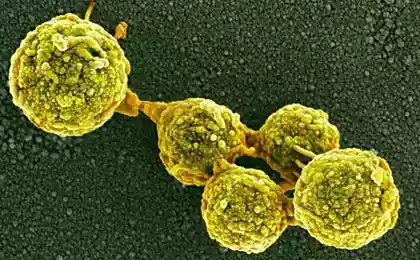

Studies (Mortensen et al., 2010) found that when people were shown photos depicting the signs of the disease, they will instantly change two characteristics: reduced desire to communicate and reduced openness to experience. Scientists noticed that when people view these images produce a characteristic gesture of repulsion with his hands. Our world is rich in very diverse cultures – the same people, but how different languages and dialects, socio-economic and political structure, family tradition and education of children, clothing, religious beliefs, customs and cuisine. In a recent article, which received wide resonance (Fincher & Thornhill, 2012), biologists from the University of new Mexico in the United States put forward the hypothesis that much of this diversity is determined parasites! Namely, the infectious diseases caused by parasites, such as leishmaniasis, dengue fever and many others.

MAN IS THE RESULT OF SELECTION

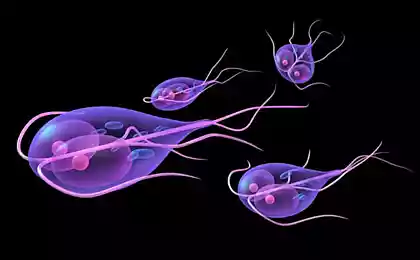

Let's start with this unusual look with the parasitic hypothesis of socialization. She says that parasites, infectious and pathogenic diseases were the main cause of disease and death, playing a key role in the selection of the person throughout the evolution. People adapted to these sources of disease protecting yourself internal immune system. Besides her, we have a behavioral immune system – the front line of helping to avoid contamination even at the distance.

So, if we find repeatedly that someone sneezes, most likely our immune system is activated. The behavioral immune system is manifested in the feelings, attitudes and behavior towards others that look bad, like sick or infected. One of the manifestations of the behavioral immune system is selective socialization. We all tend to communicate with similar to us humans.

And appear selective socialization in different ways (Fincher & Thornhill, 2008). It may be ethnocentrism is favoritism to members of their own group, and xenophobia – dislike of members of other communities and groups. Or so philopatry common – the desire to return to the place of birth to reside together with loved ones, not going beyond the familiar.

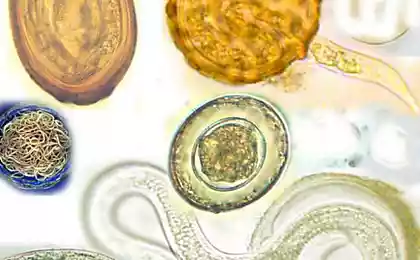

Mankind has acquired hundreds of different parasites, which have co-evolved the past few million years (Cox, 2002). Sometimes it even led to the symbiosis – so, the mitochondria, the energy producers in human cells, last – parasitic bacterium, still has its own independent DNA code (Searcy, 2003). Adapting to these bacteria, we have come up with different methods of dealing with them, and they worked out all new tricks. This is truly an endless arms race that will end soon.

EACH TRIBE IS A MUTANT

Adaptation led to the fact that we have been very resistant to some parasites and infections, living in the neighborhood. At the same time we can be vulnerable in front of strangers, brought from other areas by bacteria. This was confirmed more than once. Thus, Leishmania braziliensis – cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is transmitted through mosquito bites, was detected in 124 species in Peru and Bolivia. 124 the tribes had produced exactly 124 mutant parasite.

Parasites have evolved along with man, and that formed the intricate tapestry of a settlement of various tribes (Rougeron et al., 2009). The same pattern is observed in the villages of Sudan – each village has its own unique strain (Miller et al., 2007). In many Indian castes of their own unique types of parasites. There is a hypothesis that the caste was formed due to different adaptation to parasites (McNeill, 1998). And the more dangerous bacteria in the environment, the smaller the size of the society. Thus, in regions of high parasite stress more ethnic groups (Cashdans, 2001). And in this light it is not surprising that the closer to the southern edges, the more nationalities living on the same land area. Researcher Jared diamond in an article in Nature in 1997, wrote (Diamond, 1997), which in Europe only 63 languages, while in New Guinea about 1,000 languages.

AUTOCRACY DRAGGED IN "ALIENS"

Another interesting fact – it turns out that the ideas of collectivism and individualism are also talking about the degree of infection of infestation (Fincher et al., 2008). The more likelihood of catching a parasitic infection, the more popular in this society the idea of community. Collectivism emphasizes the boundaries between their group and other contacts between them are limited. But the individualistic approach is more open to group boundaries. People in the ideology of individualism are free to develop your group, change it and socially mobile. At the same time, collectivism is always accompanied in varying degrees of autocracy, support traditional role of women (subordinate male), and limiting the manifestations of female sexuality.

Individualism – liberal and gives her everything she wants. Interestingly, women are more free in the Nordic countries, where parasites survive with difficulty. In those places where the risk of infection is minimal, selective socialization is weakened and people are more willing and more likely to come into contact with other cultures. This leads to new opportunities in the economy and culture, exchange of goods, technologies and ideas. For example, the vast majority of innovation in China comes from Northern regions where parasitic stress (1) is lower than in the South (McNeill, 1998).

HOW PARASITES REGULATE FAMILY

We all have parents, but people differ in how they are close and dependent on her family and how deep family ties extend. In the course of evolution and in the conditions of strong parasitic stress people near you – only insurance from diseases. To stay close to each other, to limit contact with the outside world and adaptation to already existing parasites can survive.

Thus, it is vital and beneficial to invest in family, and is very dangerous to become an outcast. If you're an individualist, not a family honor and behave, not looking at the others, who will give you water and make a fire to warm you when you're sick? Tellingly, the family ties are stronger than anything in a collectivist society (Fincher & Thornhill, 2012). But there is a little bit scary and sad thought for the last fifty years, when the sanitary and hygienic norms and health care have caused significant damage to the parasitic infections, the number of divorces has reached 50%. But if the parasitic hypothesis is correct, it turns out that for the fortress of our families they said?!

RELIGION – PROTECTION FROM INVASION

If not parasites, then we may not have been familiar with the phenomenon of religion. The membership of the group has many elements that serve as the border between "their" and "strangers": the language and dialect, clothing, songs, music, cuisine and religion. Are the boundaries of different levels – external, like clothes, and deeper, as beliefs.

We can recognize a member of their group or a stranger from afar – the clothes and hair, and speaking – language and to what he believes. In this sense, religion as an element of border is no different on the national cuisine.

Parasitic stress different levels of the possibility of Contracting infectious diseases transmitted by parasites.

Participation in religious activities – exercise that requires investment: it is necessary to learn the basics, go to ceremonies, to pay and donate money and stuff. Besides, it brings certain social benefits – people increase status in the group. The more expensive the entry and maintenance of status in the Church and the stricter its rules, the higher the commitment of its followers and more devoted to their group.

The higher the probability of infection of parasitic infectious diseases, the greater will be the manifestations of religiosity. A meta-analysis (Saroglou et al., 2004) research in 15 countries found that religious people are supportive of the values of social order in an unchanged form and does not welcome the openness to change and individual autonomy. Norris and Inglehart (Norris & Inglehart, 2004) noted that religiosity is associated with gross national product – the worse people live, the more they are involved in religion. In the United States by level of religiosity in different areas it is possible to predict the level of inequality in education, income, family and racial prejudices (Delamontagne, 2010). Think about it, religion "comes" to those who are poor and uneducated. From the point of view of evolution, it is one of the adaptive ways to survive in a terrible and dangerous health conditions.

WE AND PARASITES – TOGETHER OR SEPARATELY?

Thus, the theory explains and proves many data that the prevalence of parasites and their evolution, along with man has led to the diversity of cultures in our society, determining in some measure his spirit, religion, family values, traditions and much more. As always in science, the theory has supporters and opponents. In General, scientists do not deny the influence of parasitic stress, but note that more research is needed. Some, such as (Currie & Mace, 2012), noted that parasitic stress, and many factors of ecological properties that correlate with latitude. There are climatic and economic theory (Van de Vliert, 2009), explaining the diversity of cultures climatic conditions.

The worse the conditions, the more people are protected from threats to the social mechanisms of religious, family and social system. The facts accumulate, and each year more and more.

A group of researchers (Moore et al., 2013), a recently discovered parasitic relationship between stress and preferences of women: the higher the risk of infection, the more women prefer masculine faces partners. Psychologists from the University of South Florida in Tampa (Vandello & Hettinger, 2012) supplemented the theory with research about what is happening in the so-called "cultures of honor". Typically refers to companies, which pays great attention to virginity. According to the theory of parasitic stress, the group tries to contact to create family with a foreigner because of the risk to unknown disease.

On the other hand, the group can't effectively play themselves with their own resources, practicing incest because of genetic mutations. In these circumstances, the woman becomes a valuable object, measured in its "purity". The family of the bride is interested in is to keep to the marriage of her purity in all senses, because her marriage may serve as a springboard to a higher social status of the family, if she marries a man who stands high in the hierarchy of society. Scientists have found a correlation between parasite stress and the "culture of honor".

No one wants to ruin "a valuable commodity" Smoking, alcohol or promiscuity. Research scientists will continue, but even what we know today, enough for a revolutionary change. After all, strengthening the sanitary and hygienic norms, we will not only reduce morbidity and mortality, but also spread liberal ideology, reduce the likelihood of civil wars, social, economic and gender inequality.

Maybe it's time to tell the parasites, our companions on the evolutionary path, the last "goodbye"? published

Author: Andrey Zubkov

LINKS FOR SKEPTICS

Cashdan, E. (2001). Ethnic diversity and its environmental determinants: Effects of climate, pathogens, and habitat diversity. American Anthropologist Is, 103 (4), 968-991.

Cox, F. E. G. (2002). History of human parasitology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15, 595-612.

Currie, T. E., & Mace, R. (2012). Analyses do not support the parasite-stress theory of human sociality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (02), 83-85.

Diamond, J. (1997).The Language Steamrollers. Nature, 389, 544-546.

Denic, S. & Nicholls, M. G. (2007). Genetic benefit of consanguinity through selection of genotypes protective against malaria. Human Biology, 79, 145-158.

Fincher, C. L. & Thornhill, R. (2008).Assortative sociality, limited dispersal: Infectious disease and the genesis of the global patterns of religious diversity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 275, 2587-2594.

Fincher, C. L., & Thornhill, R. (2012).Parasite-stress promotes in-group assortative sociality: The cases of strong family ties and heightened religiosity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (2), 61-79.

Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R., & Schaller, M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proceedings of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 275 (1640), 1279-1285.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1994). Why strict churches are strong. American Journal of Sociology, 99, 1180-1211.

McCleary, R. M. & Barro, R. J. (2006). Religion and political economy in an international panel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45, 149-175.

McNeill, W. H. (1998). Plagues and peoples.

Anchor.Miller, E. N., Fadl, M., Mohamed, H. S., Elzein, A., Jamieson, S.E., Cordell, H. J., Peacock, C. S., Fakiola, M., Raju, M., Khalil, E. A., Elhassan, A., Musa, A. M., Ibrahim, M. E., & Blackwell, J. M. (2007).Y chromosome lineage - and village-specific genes on chromosomes 1p22 and 6q27 control visceral leishmaniasis in Sudan. PLoS Genet, 3 (5), e71.

Moore, F. R., Coetzee, V., Contreras-Garduсo, J., Debruine, L. M., Kleisner, K., Krams, I., Marcinkowska, U., Nord, A., Perrett, D. I., Rantala, M. J.,Schaum, N., & Suzuki, T. N. (2013). Cross-cultural variation in women's preferences for cues to sex - and stress-hormones in the male face. Biology Letters, 9 (3).

Mortensen, C. R., Becker, D. V., Ackerman, J. M., Neuberg, S. L. & Kenrick, D. T. (2010) Infection breeds reticence: the effects of disease salience on selfperceptions of personality and behavioral avoidance tendencies. Psychological Science, 21, 440-447.

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rougeron, V., De MEEI, T., Hide, M., Waleckx, E., Bermudez, H., Arevalo, J., Llanos-Cuentas, A., Dujardin, J.-C., De Doncker S., Le Ray, D., Ayala, F. J., & Baсuls, A.-L. (2009). Extreme inbreeding in Leishmania braziliensis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106 (25), 10224-10229.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V. & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: a meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz''s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37 (4), 721-734.

Searcy, D. G. (2003). Metabolic integration during the evolutionary origin of mitochondria. Cell Research, 13, 229-238.

Sosis, R. & Bressler, E. R. (2003). Cooperation and commune longevity: A test of the costly signaling theory of religion. Cross-Cultural Research, 37, 211-239.

Van de Vliert, E. (2009). Climate, affluence, and culture. Cambridge University Press.

Vandello, J. A., & Hettinger, V. E. (2012). Parasite-stress, cultures of honor, and the emergence of gender bias in purity norms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (02), 95-96.

Source: www.psyh.ru/rubric/3/articles/1818/

The FACT

Studies (Mortensen et al., 2010) found that when people were shown photos depicting the signs of the disease, they will instantly change two characteristics: reduced desire to communicate and reduced openness to experience. Scientists noticed that when people view these images produce a characteristic gesture of repulsion with his hands. Our world is rich in very diverse cultures – the same people, but how different languages and dialects, socio-economic and political structure, family tradition and education of children, clothing, religious beliefs, customs and cuisine. In a recent article, which received wide resonance (Fincher & Thornhill, 2012), biologists from the University of new Mexico in the United States put forward the hypothesis that much of this diversity is determined parasites! Namely, the infectious diseases caused by parasites, such as leishmaniasis, dengue fever and many others.

MAN IS THE RESULT OF SELECTION

Let's start with this unusual look with the parasitic hypothesis of socialization. She says that parasites, infectious and pathogenic diseases were the main cause of disease and death, playing a key role in the selection of the person throughout the evolution. People adapted to these sources of disease protecting yourself internal immune system. Besides her, we have a behavioral immune system – the front line of helping to avoid contamination even at the distance.

So, if we find repeatedly that someone sneezes, most likely our immune system is activated. The behavioral immune system is manifested in the feelings, attitudes and behavior towards others that look bad, like sick or infected. One of the manifestations of the behavioral immune system is selective socialization. We all tend to communicate with similar to us humans.

And appear selective socialization in different ways (Fincher & Thornhill, 2008). It may be ethnocentrism is favoritism to members of their own group, and xenophobia – dislike of members of other communities and groups. Or so philopatry common – the desire to return to the place of birth to reside together with loved ones, not going beyond the familiar.

Mankind has acquired hundreds of different parasites, which have co-evolved the past few million years (Cox, 2002). Sometimes it even led to the symbiosis – so, the mitochondria, the energy producers in human cells, last – parasitic bacterium, still has its own independent DNA code (Searcy, 2003). Adapting to these bacteria, we have come up with different methods of dealing with them, and they worked out all new tricks. This is truly an endless arms race that will end soon.

EACH TRIBE IS A MUTANT

Adaptation led to the fact that we have been very resistant to some parasites and infections, living in the neighborhood. At the same time we can be vulnerable in front of strangers, brought from other areas by bacteria. This was confirmed more than once. Thus, Leishmania braziliensis – cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is transmitted through mosquito bites, was detected in 124 species in Peru and Bolivia. 124 the tribes had produced exactly 124 mutant parasite.

Parasites have evolved along with man, and that formed the intricate tapestry of a settlement of various tribes (Rougeron et al., 2009). The same pattern is observed in the villages of Sudan – each village has its own unique strain (Miller et al., 2007). In many Indian castes of their own unique types of parasites. There is a hypothesis that the caste was formed due to different adaptation to parasites (McNeill, 1998). And the more dangerous bacteria in the environment, the smaller the size of the society. Thus, in regions of high parasite stress more ethnic groups (Cashdans, 2001). And in this light it is not surprising that the closer to the southern edges, the more nationalities living on the same land area. Researcher Jared diamond in an article in Nature in 1997, wrote (Diamond, 1997), which in Europe only 63 languages, while in New Guinea about 1,000 languages.

AUTOCRACY DRAGGED IN "ALIENS"

Another interesting fact – it turns out that the ideas of collectivism and individualism are also talking about the degree of infection of infestation (Fincher et al., 2008). The more likelihood of catching a parasitic infection, the more popular in this society the idea of community. Collectivism emphasizes the boundaries between their group and other contacts between them are limited. But the individualistic approach is more open to group boundaries. People in the ideology of individualism are free to develop your group, change it and socially mobile. At the same time, collectivism is always accompanied in varying degrees of autocracy, support traditional role of women (subordinate male), and limiting the manifestations of female sexuality.

Individualism – liberal and gives her everything she wants. Interestingly, women are more free in the Nordic countries, where parasites survive with difficulty. In those places where the risk of infection is minimal, selective socialization is weakened and people are more willing and more likely to come into contact with other cultures. This leads to new opportunities in the economy and culture, exchange of goods, technologies and ideas. For example, the vast majority of innovation in China comes from Northern regions where parasitic stress (1) is lower than in the South (McNeill, 1998).

HOW PARASITES REGULATE FAMILY

We all have parents, but people differ in how they are close and dependent on her family and how deep family ties extend. In the course of evolution and in the conditions of strong parasitic stress people near you – only insurance from diseases. To stay close to each other, to limit contact with the outside world and adaptation to already existing parasites can survive.

Thus, it is vital and beneficial to invest in family, and is very dangerous to become an outcast. If you're an individualist, not a family honor and behave, not looking at the others, who will give you water and make a fire to warm you when you're sick? Tellingly, the family ties are stronger than anything in a collectivist society (Fincher & Thornhill, 2012). But there is a little bit scary and sad thought for the last fifty years, when the sanitary and hygienic norms and health care have caused significant damage to the parasitic infections, the number of divorces has reached 50%. But if the parasitic hypothesis is correct, it turns out that for the fortress of our families they said?!

RELIGION – PROTECTION FROM INVASION

If not parasites, then we may not have been familiar with the phenomenon of religion. The membership of the group has many elements that serve as the border between "their" and "strangers": the language and dialect, clothing, songs, music, cuisine and religion. Are the boundaries of different levels – external, like clothes, and deeper, as beliefs.

We can recognize a member of their group or a stranger from afar – the clothes and hair, and speaking – language and to what he believes. In this sense, religion as an element of border is no different on the national cuisine.

Parasitic stress different levels of the possibility of Contracting infectious diseases transmitted by parasites.

Participation in religious activities – exercise that requires investment: it is necessary to learn the basics, go to ceremonies, to pay and donate money and stuff. Besides, it brings certain social benefits – people increase status in the group. The more expensive the entry and maintenance of status in the Church and the stricter its rules, the higher the commitment of its followers and more devoted to their group.

The higher the probability of infection of parasitic infectious diseases, the greater will be the manifestations of religiosity. A meta-analysis (Saroglou et al., 2004) research in 15 countries found that religious people are supportive of the values of social order in an unchanged form and does not welcome the openness to change and individual autonomy. Norris and Inglehart (Norris & Inglehart, 2004) noted that religiosity is associated with gross national product – the worse people live, the more they are involved in religion. In the United States by level of religiosity in different areas it is possible to predict the level of inequality in education, income, family and racial prejudices (Delamontagne, 2010). Think about it, religion "comes" to those who are poor and uneducated. From the point of view of evolution, it is one of the adaptive ways to survive in a terrible and dangerous health conditions.

WE AND PARASITES – TOGETHER OR SEPARATELY?

Thus, the theory explains and proves many data that the prevalence of parasites and their evolution, along with man has led to the diversity of cultures in our society, determining in some measure his spirit, religion, family values, traditions and much more. As always in science, the theory has supporters and opponents. In General, scientists do not deny the influence of parasitic stress, but note that more research is needed. Some, such as (Currie & Mace, 2012), noted that parasitic stress, and many factors of ecological properties that correlate with latitude. There are climatic and economic theory (Van de Vliert, 2009), explaining the diversity of cultures climatic conditions.

The worse the conditions, the more people are protected from threats to the social mechanisms of religious, family and social system. The facts accumulate, and each year more and more.

A group of researchers (Moore et al., 2013), a recently discovered parasitic relationship between stress and preferences of women: the higher the risk of infection, the more women prefer masculine faces partners. Psychologists from the University of South Florida in Tampa (Vandello & Hettinger, 2012) supplemented the theory with research about what is happening in the so-called "cultures of honor". Typically refers to companies, which pays great attention to virginity. According to the theory of parasitic stress, the group tries to contact to create family with a foreigner because of the risk to unknown disease.

On the other hand, the group can't effectively play themselves with their own resources, practicing incest because of genetic mutations. In these circumstances, the woman becomes a valuable object, measured in its "purity". The family of the bride is interested in is to keep to the marriage of her purity in all senses, because her marriage may serve as a springboard to a higher social status of the family, if she marries a man who stands high in the hierarchy of society. Scientists have found a correlation between parasite stress and the "culture of honor".

No one wants to ruin "a valuable commodity" Smoking, alcohol or promiscuity. Research scientists will continue, but even what we know today, enough for a revolutionary change. After all, strengthening the sanitary and hygienic norms, we will not only reduce morbidity and mortality, but also spread liberal ideology, reduce the likelihood of civil wars, social, economic and gender inequality.

Maybe it's time to tell the parasites, our companions on the evolutionary path, the last "goodbye"? published

Author: Andrey Zubkov

LINKS FOR SKEPTICS

Cashdan, E. (2001). Ethnic diversity and its environmental determinants: Effects of climate, pathogens, and habitat diversity. American Anthropologist Is, 103 (4), 968-991.

Cox, F. E. G. (2002). History of human parasitology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15, 595-612.

Currie, T. E., & Mace, R. (2012). Analyses do not support the parasite-stress theory of human sociality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (02), 83-85.

Diamond, J. (1997).The Language Steamrollers. Nature, 389, 544-546.

Denic, S. & Nicholls, M. G. (2007). Genetic benefit of consanguinity through selection of genotypes protective against malaria. Human Biology, 79, 145-158.

Fincher, C. L. & Thornhill, R. (2008).Assortative sociality, limited dispersal: Infectious disease and the genesis of the global patterns of religious diversity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 275, 2587-2594.

Fincher, C. L., & Thornhill, R. (2012).Parasite-stress promotes in-group assortative sociality: The cases of strong family ties and heightened religiosity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (2), 61-79.

Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R., & Schaller, M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proceedings of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 275 (1640), 1279-1285.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1994). Why strict churches are strong. American Journal of Sociology, 99, 1180-1211.

McCleary, R. M. & Barro, R. J. (2006). Religion and political economy in an international panel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45, 149-175.

McNeill, W. H. (1998). Plagues and peoples.

Anchor.Miller, E. N., Fadl, M., Mohamed, H. S., Elzein, A., Jamieson, S.E., Cordell, H. J., Peacock, C. S., Fakiola, M., Raju, M., Khalil, E. A., Elhassan, A., Musa, A. M., Ibrahim, M. E., & Blackwell, J. M. (2007).Y chromosome lineage - and village-specific genes on chromosomes 1p22 and 6q27 control visceral leishmaniasis in Sudan. PLoS Genet, 3 (5), e71.

Moore, F. R., Coetzee, V., Contreras-Garduсo, J., Debruine, L. M., Kleisner, K., Krams, I., Marcinkowska, U., Nord, A., Perrett, D. I., Rantala, M. J.,Schaum, N., & Suzuki, T. N. (2013). Cross-cultural variation in women's preferences for cues to sex - and stress-hormones in the male face. Biology Letters, 9 (3).

Mortensen, C. R., Becker, D. V., Ackerman, J. M., Neuberg, S. L. & Kenrick, D. T. (2010) Infection breeds reticence: the effects of disease salience on selfperceptions of personality and behavioral avoidance tendencies. Psychological Science, 21, 440-447.

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rougeron, V., De MEEI, T., Hide, M., Waleckx, E., Bermudez, H., Arevalo, J., Llanos-Cuentas, A., Dujardin, J.-C., De Doncker S., Le Ray, D., Ayala, F. J., & Baсuls, A.-L. (2009). Extreme inbreeding in Leishmania braziliensis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106 (25), 10224-10229.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V. & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: a meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz''s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37 (4), 721-734.

Searcy, D. G. (2003). Metabolic integration during the evolutionary origin of mitochondria. Cell Research, 13, 229-238.

Sosis, R. & Bressler, E. R. (2003). Cooperation and commune longevity: A test of the costly signaling theory of religion. Cross-Cultural Research, 37, 211-239.

Van de Vliert, E. (2009). Climate, affluence, and culture. Cambridge University Press.

Vandello, J. A., & Hettinger, V. E. (2012). Parasite-stress, cultures of honor, and the emergence of gender bias in purity norms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35 (02), 95-96.

Source: www.psyh.ru/rubric/3/articles/1818/