311

Anthony Gardner: “Every Third World Has Its Own First World”

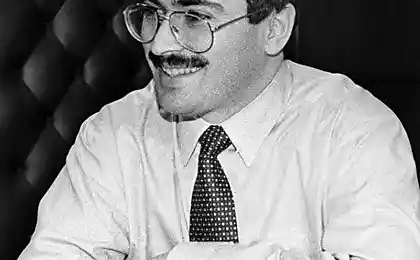

© Ben Thorp Brown

Anthony Gardner, Associate Professor of History and Theory of Contemporary Art at Oxford University, researches art politics, exhibition history, and the countries of the former socialist camp. T&P talked to him about what art politics means, whether to divide Europe into East and West, and the confrontation between art and democratic ideas.

- You have been engaged in the art of the South for a long time, and then together with Zdenka Badovinac prepared the anthology Neue Slowenische Kunst and the book Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art against Democracy. Both are due out this year. Do you see similarities between Eastern European and Southern artistic situations?

- I would not speak of Eastern Europe and the South as monolithic entities, because they have many different parts. I think there are many “Yugas,” just as there are many “Europes.” Each situation has its own conflicts and interests. Many divide Eastern Europe and Western Europe in the same way they divide the North. It seems to me that this division is not very correct, I would rather say that each “third world” has its own “first world”, and each “first world” has its own “third world”.

I think the situation in Eastern Europe is interesting because institutions there play an important role in shaping the artistic process. Moreover, Eastern Europe is important for thinking about the changes and leaps and bounds of the last 15-25 years. I wondered for a long time whether Eastern Europe had the same energy as it had not long ago. I am not sure that this region has reached the political or cultural level for which it had the potential. There are many reasons why Eastern Europe started so hard and continued with much less energy.

“Instead of thinking about how art illustrates politics, I think about the politics of the art world.”—The lecture you gave in Garage was titled “On Aesthetic Politics in the Post-Socialist Age.” The term you use brings to mind the title of Franklin Ankersmith’s book Aesthetic Politics, which deals with political representation. Did your lecture in Garage address these issues? What is “Aesthetic Policy” for you?

- I use the term aesthetic politics in a much more expected sense. Instead of thinking about how art illustrates politics, I think about the politics of the art world. In the refraction of a small local scene, politics can be expressed in what ideas become more influential, what is considered modern, and so on. Another way of thinking about this is to observe how art constructs its own politics, which does not reflect the current political situation, but allows you to look at it from an interesting angle, creates its own agenda and perhaps a new understanding of what politics can be. The second definition may refer to a variety of forms of activism, but without its inherent straightforwardness.

- His latest book is Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art Against Democracy. Can you explain its name and what it is about?

- The book opens with a reflection on why some artists in the 1970s and 1980s challenged democracy as the only possible regime for art politics. There were many ways of posing this question, but there was a more comprehensive approach, which was to ask how democracy became the main way of thinking about the politics of art. Artists pondered the legacy of the Cold War, the consequences of communism, globalization, and military invasions, trying to understand how modern democracy came to be in political theory and art, and questioning its correctness. They also explored why democracy became the mainstream theory of politics, political theory, and the arts. They were trying to understand what art could say or do to criticize the dominance of the democratic idea.

Criticism of democracy can be characterized by the concept of unbecoming, which has two meanings in English. The first is the opposite form of the verb “to become,” that is, not to become, to be destroyed, to be deconstructed. The second is to be inappropriate, inappropriate, indecent. The meanings of the word allow us to think about what can be acceptable in the politics of art. An example of this approach is Ilya Kabakov, who still calls himself a Soviet artist, despite the fact that the USSR no longer exists. Maybe he does it nostalgically, maybe critically. What does it mean to identify with a state that no longer exists? It's a kind of non-identification -- instead of identifying with some larger community, creating something different.

Instead of globality, I would prefer to talk about translocality. To be translocal means to be aware of what is happening and what is happening next to you, but also to know languages and foreign realities. During the work on the book, I was interested in artists who were problematizing the notion of geographical boundaries that still serve an important function in a globalized Europe. It is foolish to assume that borders will disappear after globalization. I'm interested in artists who complicate the idea of a standard identity that obeys national borders. I think it's important to think about the future of art in general.

Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art Against Democracy

- In one of your articles, you wrote about the need to break the traditional hierarchy of the global and the local, and to re-talk about globality and universality. What solutions to the global problem do you propose now?

- I don’t think the term “global” is very good, even though I used it. Here, for example, in Russia there is a huge difference between the artistic situations in Moscow, St. Petersburg and, for example, Nizhny Novgorod. Instead of globality, I would prefer to talk about translocality. To be translocal means to be aware of what is happening and what has been happening near you, but at the same time to know languages and foreign realities, to establish ties between, for example, Moscow and Ljubljana.

- Given the strategy of translocality, what do you see as the development paths for institutions in Russia?

- It is difficult for me to talk about the Russian situation, but the most interesting local institutions that I have worked with or visited are those that have worked with the local art community, with its energy, expectations and frustrations. They have always been passionate about new ideas, new ways of producing them, and cultural exchange.

- Now the former socialist countries are in a rather difficult situation related to the conflict in Ukraine. What strategies do you see for artistic collaboration in a complex political environment?

- Tough question... In fact, there are many different strategies, because it would be terrible if there was only one, because it would be quickly absorbed by the problem situation that it is trying to cope with or become expected. In my opinion, the last thing art should be is expected.

Source: theoryandpractice.ru