226

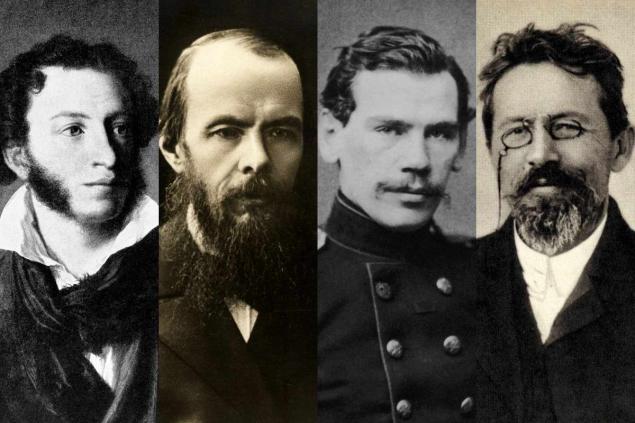

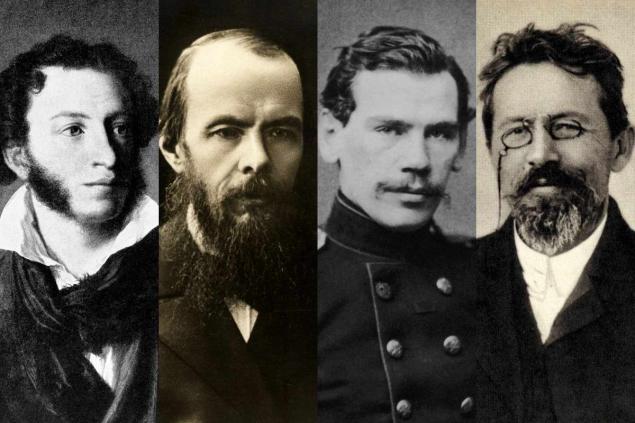

Strange names that Russian writers awarded wives

As the English proverb rightly states, behind every great man is a great woman. This applies to politicians and businessmen, inventors and generals, but first of all, of course, poets. A poet without a muse is not a poet. Wives of writers and poets serve as a source of their inspiration and selflessly take on the burden of everyday problems.

GettyImages What's a master of words? They speak beautifully to their friends, over which time itself does not rule. Thanks to the letters that have preserved them, we have a rare chance to learn what the great Russian writers of the nineteenth century were like in ordinary life and how they behaved with loved ones.

Wives of writers Alexander Pushkin and Natalia Goncharova Throughout their life together, Pushkin and Natalia Nikolaevna parted nine times. During the forced separation, the poet wrote more than 70 letters to his wife. Most often, he calls her an angel: Goodbye, lovely angel. Whole tips of your wings, as Voltaire used to say to people who didn't cost you.

A caring and loving husband, Pushkin constantly cares about his wife, gives her advice on how to protect herself. On December 16, 1831, he wrote from Moscow: My dear friend, you are very nice, you write to me often, one trouble: your letters do not please me. What is it? Fainting or nausea? Have you seen your grandmother? Did they give you blood? All this horror bothers me.

The more I think, the clearer I see what I did stupidly to leave you. Without me, you're gonna throw something away. You're gonna throw that away. Why don't you go? And you gave me your word of honor that you would walk 2 hours a day. Is that good? It seems that the problem of insufficient motor activity was relevant 200 years ago.

Pushkin never tires of reminding Natalia of her beauty. And not only external, but also internal: “Have you looked in the mirror and convinced yourself that nothing can be compared with your face in the world, and I love your soul even more than your face.”

And, of course, he is interested in everything related to children: “Does Masha say?” Does he? What teeth? What is my toothless Puskin? he wrote to his wife and immediately added: “These are my teeth!”

By the way, few people know that it was Mashenka, later Maria Aleksandrovna Hartung, the only one of all Pushkin’s children, who lived to see the October Revolution. And about her difficult and eventful fate you can learn from our article.

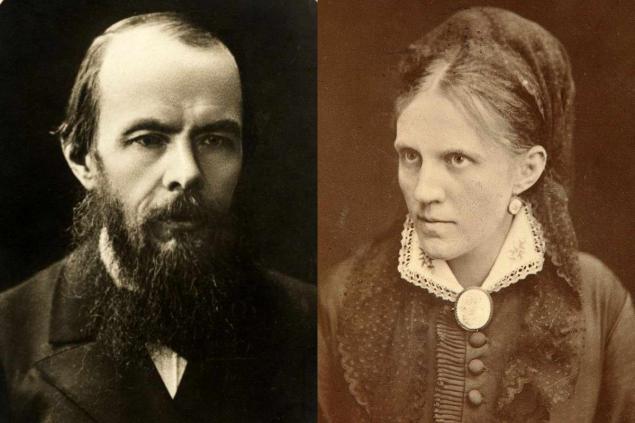

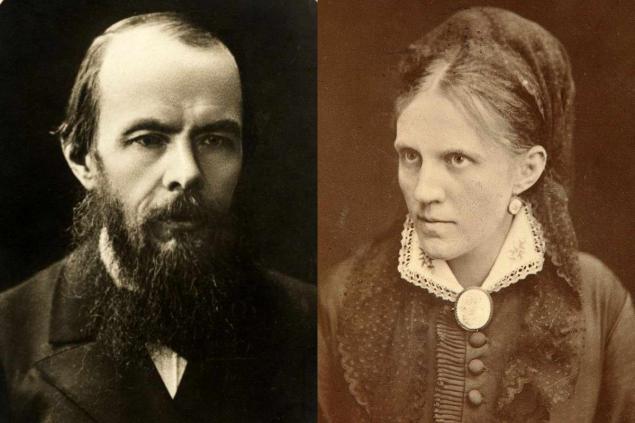

Fyodor Dostoevsky and Anna Snitkina Anna Grigorievna Snitkina became Dostoevsky’s wife on February 15, 1867. She was a stenographer and helped prepare the novel The Gambler for publication. So the novel was the beginning of the novel of her whole life.

GettyImages Fedor Mikhailovich was an avid player himself. After another loss, he wrote to his wife: Anya, dear, my friend, my wife, forgive me, do not call me a scoundrel! I committed a crime, I lost everything you sent me.

My dear angel, yesterday I experienced a terrible torment: I am going to the post office as I finished my letter to you, and suddenly I am told that there is no letter from you. My legs have shattered.

As for Anna Grigorievna, she valued Dostoevsky’s letters more than all his novels. And she was right. Later, they came out as a separate book, were translated into several languages and appeared before descendants as a real literary monument to a loving wife and faithful friend.

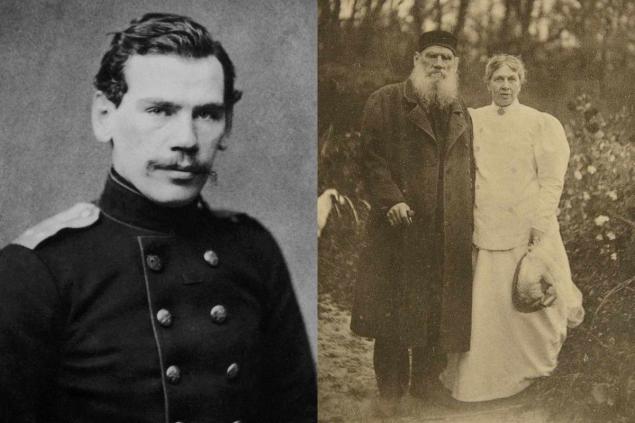

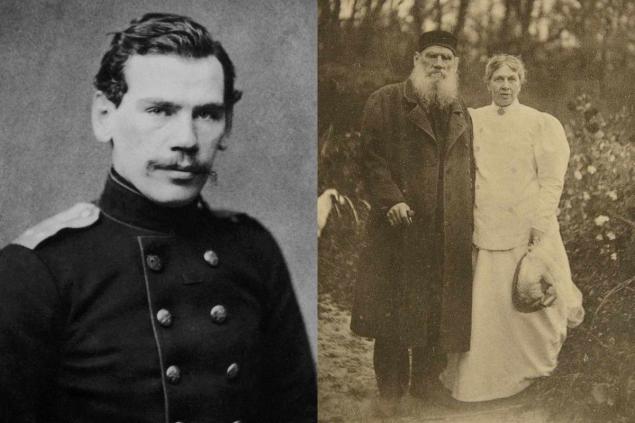

Leo Tolstoy and Sophia Bers Sophia Bers married Leo Tolstoy in 1862, when she was barely 18 years old. During her marriage, she gave birth to 13 children and inspired Tolstoy to write his main novels. At the same time, Sofia Andreevna rewrote War and Peace several times, becoming the writer’s secretary and literary agent in one person.

GettyImages Lev Nikolaevich was stingy in describing his feelings. But when emotions take over, it becomes clear how he loves his wife: "Incredible happiness ..." It can't just end with life. I lived to be 34 years old and I didn’t know it was possible to love and be so happy. Now I constantly feel as if I have stolen an undeserved, illegitimate, unassigned happiness. Here she comes, I hear her, and so well.”

GettyImages In letters, he calls his wife a sweet friend and sweet: You must be unhappy with me, dear friend, for my letters. They probably came out overcast, as I had been overcast for those 2 or 1 1⁄2 days.

Alexander Griboyedov and Nino Chavchavadze Georgian Princess Nina Chavchavadze and State Counselor, Russian Ambassador to Persia Alexander Griboyedov got married on August 22, 1828. Two months earlier, the writer proposed, and a week after the wedding, he was forced to return to Persia.

GettyImages: My priceless friend, I feel sorry for you, sad without you as much as possible. Now I really feel what it means to love. Let us endure, my angel, and pray to God that we will never be separated again, Griboyedov, 33, wrote to his pregnant wife from Persia.

“Write to me more often, my angel Ninobi. All yours. A.G. January 15, 1829. Tehran, read one of Griboyedov’s last letters to his wife. Two weeks later, he was killed in an attack by Islamic fanatics on the embassy.

Nino Chavchavadze never married again and did not take off mourning clothes for almost 30 years. For the fact that she kept the memory of her deceased husband for the rest of her life, she was nicknamed the “black rose of Tiflis”.

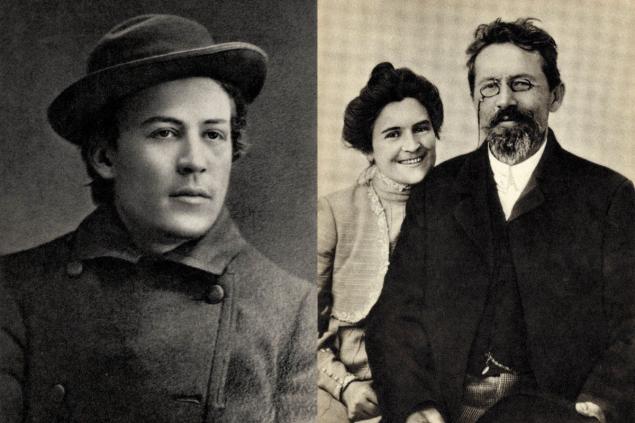

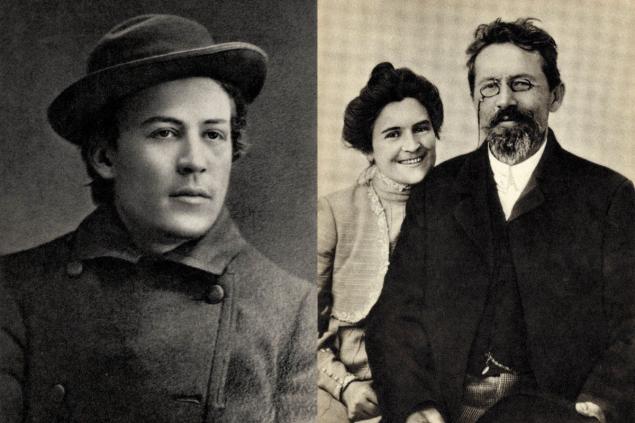

Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper Chekhov’s letters to the leading actress of the Moscow Art Theatre Olga Knipper documented the beginning of their novel with documentary accuracy. On May 20, 1900, he wrote to her from Yalta to Moscow: “Sweet, delightful actress, hello!” How are you? How are you feeling? And after three months: “Dear Olya, my joy, hello!”

Later, they began to conduct a rich correspondence (more than 400 letters survived), in which they exchanged two tender nicknames and jokes that only they understand. Farewell, goodbye, dear grandmother, may the holy angels keep you. Don’t be angry with me, love, don’t be a moron, be a smart girl, wrote Olga Chekhov.

“I will come to Moscow in the morning, the fast trains have already started to run. Oh, my blanket! Oh, calf cutlets! Dog, dog, I missed you so much!

And his wife answered him in tone: "Kiss you, my dear head, kiss softly and hotly eyes, hair, lips, cheeks; I often fly mentally to you and sit in the study and in the bedroom with you and with you." Love your dog.

As you can see, the classics of Russian literature were just people with their own weaknesses. They rejoiced, saddened, dreamed, hoped, joked and loved - just like the rest of us. Reading their heartwarming letters, you realize that love is the most precious thing we have.

GettyImages What's a master of words? They speak beautifully to their friends, over which time itself does not rule. Thanks to the letters that have preserved them, we have a rare chance to learn what the great Russian writers of the nineteenth century were like in ordinary life and how they behaved with loved ones.

Wives of writers Alexander Pushkin and Natalia Goncharova Throughout their life together, Pushkin and Natalia Nikolaevna parted nine times. During the forced separation, the poet wrote more than 70 letters to his wife. Most often, he calls her an angel: Goodbye, lovely angel. Whole tips of your wings, as Voltaire used to say to people who didn't cost you.

A caring and loving husband, Pushkin constantly cares about his wife, gives her advice on how to protect herself. On December 16, 1831, he wrote from Moscow: My dear friend, you are very nice, you write to me often, one trouble: your letters do not please me. What is it? Fainting or nausea? Have you seen your grandmother? Did they give you blood? All this horror bothers me.

The more I think, the clearer I see what I did stupidly to leave you. Without me, you're gonna throw something away. You're gonna throw that away. Why don't you go? And you gave me your word of honor that you would walk 2 hours a day. Is that good? It seems that the problem of insufficient motor activity was relevant 200 years ago.

Pushkin never tires of reminding Natalia of her beauty. And not only external, but also internal: “Have you looked in the mirror and convinced yourself that nothing can be compared with your face in the world, and I love your soul even more than your face.”

And, of course, he is interested in everything related to children: “Does Masha say?” Does he? What teeth? What is my toothless Puskin? he wrote to his wife and immediately added: “These are my teeth!”

By the way, few people know that it was Mashenka, later Maria Aleksandrovna Hartung, the only one of all Pushkin’s children, who lived to see the October Revolution. And about her difficult and eventful fate you can learn from our article.

Fyodor Dostoevsky and Anna Snitkina Anna Grigorievna Snitkina became Dostoevsky’s wife on February 15, 1867. She was a stenographer and helped prepare the novel The Gambler for publication. So the novel was the beginning of the novel of her whole life.

GettyImages Fedor Mikhailovich was an avid player himself. After another loss, he wrote to his wife: Anya, dear, my friend, my wife, forgive me, do not call me a scoundrel! I committed a crime, I lost everything you sent me.

My dear angel, yesterday I experienced a terrible torment: I am going to the post office as I finished my letter to you, and suddenly I am told that there is no letter from you. My legs have shattered.

As for Anna Grigorievna, she valued Dostoevsky’s letters more than all his novels. And she was right. Later, they came out as a separate book, were translated into several languages and appeared before descendants as a real literary monument to a loving wife and faithful friend.

Leo Tolstoy and Sophia Bers Sophia Bers married Leo Tolstoy in 1862, when she was barely 18 years old. During her marriage, she gave birth to 13 children and inspired Tolstoy to write his main novels. At the same time, Sofia Andreevna rewrote War and Peace several times, becoming the writer’s secretary and literary agent in one person.

GettyImages Lev Nikolaevich was stingy in describing his feelings. But when emotions take over, it becomes clear how he loves his wife: "Incredible happiness ..." It can't just end with life. I lived to be 34 years old and I didn’t know it was possible to love and be so happy. Now I constantly feel as if I have stolen an undeserved, illegitimate, unassigned happiness. Here she comes, I hear her, and so well.”

GettyImages In letters, he calls his wife a sweet friend and sweet: You must be unhappy with me, dear friend, for my letters. They probably came out overcast, as I had been overcast for those 2 or 1 1⁄2 days.

Alexander Griboyedov and Nino Chavchavadze Georgian Princess Nina Chavchavadze and State Counselor, Russian Ambassador to Persia Alexander Griboyedov got married on August 22, 1828. Two months earlier, the writer proposed, and a week after the wedding, he was forced to return to Persia.

GettyImages: My priceless friend, I feel sorry for you, sad without you as much as possible. Now I really feel what it means to love. Let us endure, my angel, and pray to God that we will never be separated again, Griboyedov, 33, wrote to his pregnant wife from Persia.

“Write to me more often, my angel Ninobi. All yours. A.G. January 15, 1829. Tehran, read one of Griboyedov’s last letters to his wife. Two weeks later, he was killed in an attack by Islamic fanatics on the embassy.

Nino Chavchavadze never married again and did not take off mourning clothes for almost 30 years. For the fact that she kept the memory of her deceased husband for the rest of her life, she was nicknamed the “black rose of Tiflis”.

Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper Chekhov’s letters to the leading actress of the Moscow Art Theatre Olga Knipper documented the beginning of their novel with documentary accuracy. On May 20, 1900, he wrote to her from Yalta to Moscow: “Sweet, delightful actress, hello!” How are you? How are you feeling? And after three months: “Dear Olya, my joy, hello!”

Later, they began to conduct a rich correspondence (more than 400 letters survived), in which they exchanged two tender nicknames and jokes that only they understand. Farewell, goodbye, dear grandmother, may the holy angels keep you. Don’t be angry with me, love, don’t be a moron, be a smart girl, wrote Olga Chekhov.

“I will come to Moscow in the morning, the fast trains have already started to run. Oh, my blanket! Oh, calf cutlets! Dog, dog, I missed you so much!

And his wife answered him in tone: "Kiss you, my dear head, kiss softly and hotly eyes, hair, lips, cheeks; I often fly mentally to you and sit in the study and in the bedroom with you and with you." Love your dog.

As you can see, the classics of Russian literature were just people with their own weaknesses. They rejoiced, saddened, dreamed, hoped, joked and loved - just like the rest of us. Reading their heartwarming letters, you realize that love is the most precious thing we have.

Is it necessary to plan a pregnancy, if the parents fit?

Actions that betray a simpleton in a future daughter-in-law, although she is building a socialite.