204

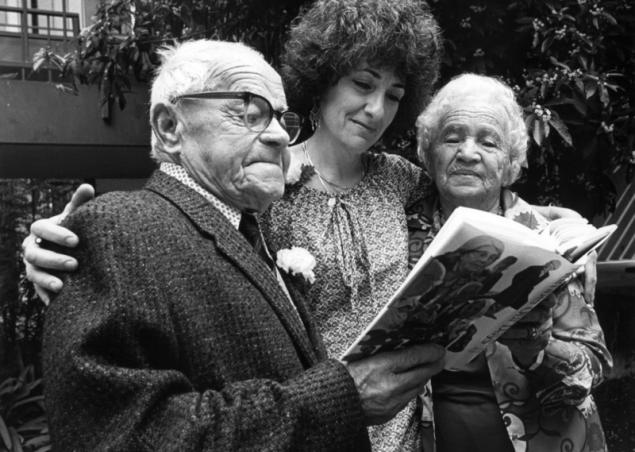

Barbara Meyerhoff: How we grow a soul

For many years I have worked with the elderly and the elderly. All this time, I think, "Without a listener, we're all rejected." Loneliness deprives us of what is rightfully ours.”

It is as if at birth each of us is given a separate story (and each birth story is in a sense a story of separation), but we do not exist until someone recognizes us, until someone sees us.

There was no Adam until Eve said, "There you are." Hey!

But what if they didn’t hear us? What will become of our history?

What happens to the one who has lost his innate right, to the abandoned listener, to the one who does not understand himself? He will fall into despair, throw ugly tantrums. Not the best way to attract attention, but hysterics always have witnesses.

Hysteria hurts, takes away pride, and yet it is better than indifference.

In The Anatomy of Melancholy, Richard Barton says:The threat of oblivion is the heaviest stone that melancholy can launch into a person.?

Maybe something worse than forgetting? For example, the loss of the feeling that you existed on earth.

I felt in my work that Barton was right. The heaviest burden that a person can bear is the weight of memories that only testify to the fact that he lived, that there was and is a meaning in his life.

Let us return to the question of the influence of history on the listener.

Half of the tragedy is to be unheard and unseen, while the other is not to hear or see.

Why? If I say that in storytelling we grow the soul, then the storytelling process itself is a partnership.

He who speaks grows the soul. He who hears and sees, in a sense, grows the soul.

Let's move on to examples. I worked with a Hungarian survivor. When the boy was 11, the family knew that the quiet time was over. He was told to pack up in advance, as he would have to leave in a hurry. He walked around the room and chose what he would take with him. I am awestruck by the thought of the boy thinking about what to save among his childhood belongings.

Now I see with my own eyes how the elderly walk around their homes and choose what to take with them to the hospital or to the nursing home. Each object is considered as a reservoir for memories, as a container for the whole world. “Do I have to leave him?”

We ask ourselves this question constantly, disassembling our cabinets and nightstands.Someone can't throw away a bunch of old letters. It's not just paper and ink - it's a piece of life.

Let's go back to the eleven-year-old. He walks around the room feeling that change is coming. His current life is running out: what to take with you? He froze at the choice.

A little later he stuffs two boxes of shoes. In one are photos with his family, his own poems, a postcard from his girlfriend - all the treasures of the boy, his autobiography in things. In another: spare shoes, linen, handkerchief, knife and watch... perhaps a toothbrush.

He'll come back from school and hear, "Run!" He'll grab a shoebox. They'll run.

Halfway through, he'll open the box and realize he's grabbed the wrong one: there's a handkerchief, shoes and a toothbrush in this one.

He'll think, "Who did I put this box together for?" Who did you put that for? What will the other box tell the one who finds it?

Now that boy grew up and says, "It was like I was standing by the sea with a box under my arm." It's like being pushed in the back and I'm slow. I'm worried I'll drown with her. It's like I'm throwing one of the boxes back to the shore for someone to catch it.

It sounds like “Toughlin was here,” don’t you think? Or scratches on the wall. Or the words of the hero of my other book.

In Few Days, Shmuel talks about the significance of death in light of the fact that his whole shtetl ate the Holocaust. He says:

“Growing old and dying is not the worst thing for a man. The problem is that I keep going back in my mind, but there is no way to go back. There is no return, nothing left, no continuation. What is the value of life? Why did we even start living? It's coming to an end. Growing old in my town would be a different matter. Now it's all gone.

I carry everything and everyone – people, places, I lift them on my shoulders and drag them.

I see the old rabbi. Workers harnessed to carts. A man who strapped a child with a piece of cloth walking from Vistula: no money, no home, no food. His dream is to find a horse, that dream will not come true. Now I'm carrying it. He won't see a horse, but at least he'll have a chance to stay in his native land.

With all the poverty, with all the troubles, it would be enough for me to keep the place. Old people like me don't need much. But I come back from my memories and realize that there is nothing. Everything disappeared without a trace, erased like a trace of a pencil with a swallow. So leaving life takes on a new meaning for me.

Saying goodbye to one life is nonsense. But to let go of all these lives that I carry within me is a grief of a very different scale.?

We die without giving up our boxes and live without catching strangers. One destroyed, the other lost. But I see the younger generation starting to change things.

Young people strive to reunite the torn, to unearth the history of a kind. They dig deeper than looking for a document with an ancestral tree. They reclaim themselves, they reclaim the past they have every right to: it is ours and no one else’s.

We're expanding. In the fourth dimension, time, we are aware of ourselves, and without it there is no soul in us.

The soul is not only in life itself, it is also in the knowledge that one lives, and in the conscious decision to be present in life, to pay attention to it. Hunger for the past gives a lot of strength, a lot of opportunity in the desire to demand what is otherwise lost.

History as Equipment for Living by Barbara Myerhoff

Translated by Elena Truskova

Those we love and those we hate are our mirrors.The soul does not think, it knows.

Source: anotherindianwinter.ru/post/143103729848/barbarameyerhoffstories2

It is as if at birth each of us is given a separate story (and each birth story is in a sense a story of separation), but we do not exist until someone recognizes us, until someone sees us.

There was no Adam until Eve said, "There you are." Hey!

But what if they didn’t hear us? What will become of our history?

What happens to the one who has lost his innate right, to the abandoned listener, to the one who does not understand himself? He will fall into despair, throw ugly tantrums. Not the best way to attract attention, but hysterics always have witnesses.

Hysteria hurts, takes away pride, and yet it is better than indifference.

In The Anatomy of Melancholy, Richard Barton says:The threat of oblivion is the heaviest stone that melancholy can launch into a person.?

Maybe something worse than forgetting? For example, the loss of the feeling that you existed on earth.

I felt in my work that Barton was right. The heaviest burden that a person can bear is the weight of memories that only testify to the fact that he lived, that there was and is a meaning in his life.

Let us return to the question of the influence of history on the listener.

Half of the tragedy is to be unheard and unseen, while the other is not to hear or see.

Why? If I say that in storytelling we grow the soul, then the storytelling process itself is a partnership.

He who speaks grows the soul. He who hears and sees, in a sense, grows the soul.

Let's move on to examples. I worked with a Hungarian survivor. When the boy was 11, the family knew that the quiet time was over. He was told to pack up in advance, as he would have to leave in a hurry. He walked around the room and chose what he would take with him. I am awestruck by the thought of the boy thinking about what to save among his childhood belongings.

Now I see with my own eyes how the elderly walk around their homes and choose what to take with them to the hospital or to the nursing home. Each object is considered as a reservoir for memories, as a container for the whole world. “Do I have to leave him?”

We ask ourselves this question constantly, disassembling our cabinets and nightstands.Someone can't throw away a bunch of old letters. It's not just paper and ink - it's a piece of life.

Let's go back to the eleven-year-old. He walks around the room feeling that change is coming. His current life is running out: what to take with you? He froze at the choice.

A little later he stuffs two boxes of shoes. In one are photos with his family, his own poems, a postcard from his girlfriend - all the treasures of the boy, his autobiography in things. In another: spare shoes, linen, handkerchief, knife and watch... perhaps a toothbrush.

He'll come back from school and hear, "Run!" He'll grab a shoebox. They'll run.

Halfway through, he'll open the box and realize he's grabbed the wrong one: there's a handkerchief, shoes and a toothbrush in this one.

He'll think, "Who did I put this box together for?" Who did you put that for? What will the other box tell the one who finds it?

Now that boy grew up and says, "It was like I was standing by the sea with a box under my arm." It's like being pushed in the back and I'm slow. I'm worried I'll drown with her. It's like I'm throwing one of the boxes back to the shore for someone to catch it.

It sounds like “Toughlin was here,” don’t you think? Or scratches on the wall. Or the words of the hero of my other book.

In Few Days, Shmuel talks about the significance of death in light of the fact that his whole shtetl ate the Holocaust. He says:

“Growing old and dying is not the worst thing for a man. The problem is that I keep going back in my mind, but there is no way to go back. There is no return, nothing left, no continuation. What is the value of life? Why did we even start living? It's coming to an end. Growing old in my town would be a different matter. Now it's all gone.

I carry everything and everyone – people, places, I lift them on my shoulders and drag them.

I see the old rabbi. Workers harnessed to carts. A man who strapped a child with a piece of cloth walking from Vistula: no money, no home, no food. His dream is to find a horse, that dream will not come true. Now I'm carrying it. He won't see a horse, but at least he'll have a chance to stay in his native land.

With all the poverty, with all the troubles, it would be enough for me to keep the place. Old people like me don't need much. But I come back from my memories and realize that there is nothing. Everything disappeared without a trace, erased like a trace of a pencil with a swallow. So leaving life takes on a new meaning for me.

Saying goodbye to one life is nonsense. But to let go of all these lives that I carry within me is a grief of a very different scale.?

We die without giving up our boxes and live without catching strangers. One destroyed, the other lost. But I see the younger generation starting to change things.

Young people strive to reunite the torn, to unearth the history of a kind. They dig deeper than looking for a document with an ancestral tree. They reclaim themselves, they reclaim the past they have every right to: it is ours and no one else’s.

We're expanding. In the fourth dimension, time, we are aware of ourselves, and without it there is no soul in us.

The soul is not only in life itself, it is also in the knowledge that one lives, and in the conscious decision to be present in life, to pay attention to it. Hunger for the past gives a lot of strength, a lot of opportunity in the desire to demand what is otherwise lost.

History as Equipment for Living by Barbara Myerhoff

Translated by Elena Truskova

Those we love and those we hate are our mirrors.The soul does not think, it knows.

Source: anotherindianwinter.ru/post/143103729848/barbarameyerhoffstories2

How to go to sea without leaving home

Hydrogen peroxide: amazing healing properties and applications