325

Why do we marry the wrong people?

Anyone we can marry will naturally not be the right fit for us. It would be wise to be acceptably pessimistic. Perfection is impossible. Misfortune is a constant quantity. And yet, sometimes we see couples with such a basic, so striking inconsistency; such a deep incompatibility that we can conclude that there is something more behind the usual frustrations and strains of a long-term relationship: some people just shouldn't be together.

How do these mistakes happen? So easy and regular, that's terrifying. It turns out that marrying the wrong person is one of the easiest and most expensive mistakes any one of us can make (and it puts a huge burden on the state, employers and the next generation), it goes beyond anything, it's almost criminal, that the issue of smart marriage is not a national and personal issue like traffic safety or smoking. And that's even sadder, because the truth is, the reasons why people make bad choices are easy to stand out and completely unsurprising at their core. It can be broken down into the following main categories. First, we don't understand ourselves.

When we first look for a partner, the demands we make are colored by a beautiful nonspecific sentimental ambiguity: we will say that we really want to find someone who is “kind” or “fun with,” who is “attractive” or “adventurous.”

Not that these are bad desires, they are just not even close enough to understand what we want in order for us to have a chance to be happy or, more precisely, not constantly unhappy.

We're all particularly crazy. We are certainly neurotic, unbalanced, and immature, but we don’t know the details, because no one has ever encouraged us to look for them. Thus, the urgent, the main task of any lover is to cope with the specific nuances of his own madness. They must become corresponding to their own neuroses. They need to understand where it came from, what made them so, and, most importantly, what kind of people provoke or comfort them. A good partnership is not between two healthy people (such are not on the planet), it is between two weak-minded people who are able or lucky to find a non-conscious agreement between two relative madnesses.

The idea that we may not be very complex as humans should be a wake-up call for any prospective partner. It's just a question of where the problems lie: maybe we have a hidden tendency to get angry when someone disagrees with us, or we can only relax when we work, or we're kind of uneasy about intimacy after sex, or we've never been good at explaining why we worry. These are the problems that, decades later, create catastrophes that we need to know about in advance in order to find people who are structurally optimal to withstand them. The standard question on any early date should be very simple: “What are you crazy about?”

The problem is that knowing our own neuroses is not easy. It can take years and take situations we've never been in. Before marriage, we rarely get involved in a dynamic that properly holds the mirror for our disorders. When a less serious relationship threatens to reveal the complexities of our nature, we tend to blame our partner and say it’s over. As for our friends, they predictably don't care so much about us to have any motive to explore the real us. They just want to have a good evening. We are blind to the weaknesses of our characters. By themselves, when we’re furious, we don’t scream if there’s no one to listen — and so we overlook our true, desperate power of rage. Or we work all the time without thinking, until no one invites us home for dinner — how maniacally we use work to gain a sense of control over life — and what hell can we do to anyone who tries to stop us? At night, all we feel is a desire to hug someone sweetly, but we do not have the opportunity to meet our avoiding intimacy side, which can make us cold and alien, even if we feel deeply committed to someone. One of the greatest privileges of being alone is the flattering illusion of being calm and comfortable.

With such a poor understanding of our character, it is not surprising that we cannot know who we are looking for.

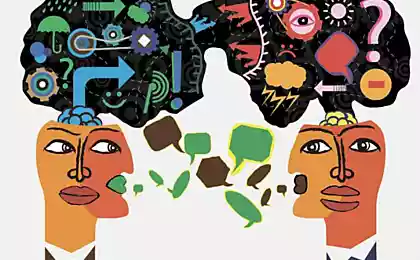

Second, we don't understand other people.

This problem is complicated by the fact that other people are at the same low level of self-knowledge as we are. No matter how well-intentioned they are, they can't understand either, let alone tell us what's wrong with them.

Naturally, we throw test stones in an attempt to recognize them. We go and visit their families, sometimes places where they studied as children, we look at pictures, we meet with their friends. It all makes me feel like we've prepared. But it's kind of like a novice pilot would imagine he could fly after he'd run a paper airplane in a room.

In a wiser society, future partners will guide each other through detailed psychological testing and be sent for long evaluations by teams of psychologists. By 2100, this will no longer sound like a joke. It will be a mystery why humanity took so long.

We need to know the inner workings of the psyche of the person we want to marry. We need to know their attitudes and attitudes about power, humiliation, introspection, sexual intimacy, projections, money, children, aging, fidelity, and a hundred other things. This knowledge cannot be obtained in ordinary conversation.

In the absence of all that, we are most driven by what they look like. It seems that so much information can be gathered in what their eyes, nose, forehead shape, wrinkle distribution, smile... But it's like thinking that a picture of a nuclear plant outside can tell us everything we need to know about atom fission.

We project a series of perfections on loved ones based on very modest evidence. In the representation of the whole personality, out of small but memorable details, we do to the inner character of man what our sight does to the sketch of the face.

We don't see anyone in this picture without nostrils, with eight strands of hair and no eyelashes. We fill in the missing parts without noticing how we do it. Our brains are trained to take small visual cues and construct whole shapes out of them, and we do the same when it comes to the character of our future spouse. We pay dearly for the fact that, far more than we assume, we are artists very well refined reality.

The level of knowledge we need to process for marriage is higher than our society is willing to support, recognize, and reconcile—so our social practices around the family are deeply flawed.

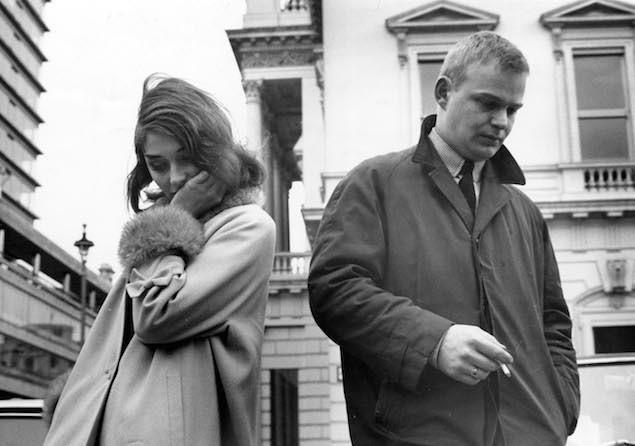

Third, we are not used to being happy.

We believe we seek happiness in love, but it’s not that simple. What we’re really looking for is something that’s familiar — something that could complicate any happiness plans we have.

We recreate in adult relationships something from the feelings we learned as children. We were children when we first learned and understood what love meant. But unfortunately, the lessons we learned may not be so simple. The love we have learned as children may be woven with another, less pleasurable dynamic: being controlled, feeling humiliated, being abandoned, not communicating, suffering shorter.

As adults, we reject some of the healthy candidates we run into, not because they are wrong, but because they are too balanced (too mature, too understanding, too reliable), and this correctness looks unfamiliar and alien, even painful. Instead, we rush to those candidates that our unconscious reaches for, not because they will make us feel good, but because they will frustrate us in a familiar way.

We marry the wrong people because the right ones don't look that way -- undeservedly; because we don't have health experiences, because being loved completely isn't associated with a sense of contentment.

Fourth, being alone is so terrible.

If being alone is unbearable, then no one can be in the right state of consciousness to rationally choose a partner. We need to be absolutely at peace with the prospect of years of loneliness if we want to have a chance to form a good relationship. Or we like not to be alone more than we love a partner who fits us the way we are.

Unfortunately, society, after a certain age, makes loneliness dangerously unpleasant. Social life withers, couples feel threatened in the independence of singles to invite them too often, a person feels like a freak going alone to the movies. Sex is also hard to get. With all the new gadgets and supposed freedoms of modernity, it can be very difficult to end up in bed with someone, and waiting to do so regularly after 30 is associated with frustration.

It is much better to rebuild society on the principle of university or dormitory - with catering, common amenities, constant parties and sexual mixing. In this case, anyone who decides to marry will be sure to do so for reasons of the benefits of pairing rather than avoiding the negative side of loneliness.

When sex was only available in marriage at all, people realized that it led to marriage for the wrong reasons: to get something that was artificially restricted in society as such. People are free to make better choices about who to marry now that they're not just desperate for sex.

But in other areas, the deficit remains. When socializing in a company is only available to couples, then people will compose them just to rid themselves of loneliness. It is time to free “companionship” from the fetters of pairing, to make it as accessible as the freedom fighters wanted to make sex.

Fifth: The great prestige of instincts

In ancient times, marriage was a rational affair; it was all about connecting your piece of land with theirs. It was cold, ruthless and unrelated to the happiness of the protagonists. We're still traumatized by this.

We replaced marriage for reasons of instinct with romantic marriage. This dictates that the only way to get married is to feel for the other person. If someone feels like they are “loving,” that’s enough. No more questions. The feeling celebrated triumph. Others only applaud his appearance, respecting how the descent of the divine spirit can be respected. Parents may be horrified, but they must assume that only a couple knows the truth. We have had a collective reaction over the past three hundred years to thousands of years of ruthless intervention based on prejudice, snobbery and lack of imagination.

The previous “marriage of convenience” was so pedantic and prudent that one of the qualities of marriage from the senses seems that a person should not really think about why he is getting married. Analysis of the solution feels “unromantic.” Drawing tables for and against seems absurd and cold. The most romantic thing one can do is propose quickly and suddenly, perhaps within a week or a few, in a rush of enthusiasm - without any chance of making the terrible "reflections" that guaranteed sadness to people thousands of years before. The recklessness of the script is also a sign that marriage will be fine, precisely because the old type of “security” was a danger to happiness.

Sixth: We don't go to the School of Love

It is time for a third type of marriage. Psychological marriage. One in which one does not marry for the sake of the land, and not only because of “feeling”, but only when the “feeling” has been properly tested under the auspices of mature awareness of the psychology of oneself and of the other.

We are currently getting married without any information. We hardly read books on special topics, don’t spend more than a little time with our children, don’t question other married couples or speak sincerely to divorced couples. We go into this without any inner understanding of why the marriage breaks apart, except that we assume that the participants are stupid or lack of imagination.

In the era of marriage of convenience, the following criteria were considered:

- Who are their parents?

- how much land they have.

- how culturally close they are.

In the Romantic era, the following signs showed that everything was right.

You can’t stop thinking about your lover.

Have sexual passion

- Like each other.

- can communicate for a long time.

We need a new set of criteria. We need to know:

- what they're crazy about.

How they can raise children together

How can they develop together?

How can they remain friends?

Seventh: We want to freeze happiness.

We are doomed and desperate to insist on making pleasant things permanent. We want to have a car that we like, we want to live in a country that we like as tourists. And we want to get married to a person that we have an amazing time with.

We imagine that marriage is the guarantee of the happiness that we enjoy with someone. That he will make permanent what is otherwise fleeting. This will help us to catch the joy in the bottle - the joy we felt when the idea to propose first came to our mind: in Venice, in the lagoon, on a yacht, with the evening sun throwing golden glare all over the sea, the prospect of dinner in a small fish restaurant, with a loved one in a cashmere sweater in our arms ... We marry to make that feeling permanent.

Unfortunately, there is no causal relationship between marriage and these feelings. The feelings were about Venice, the time of year, the rest of work, the pleasure of dinner, two months of dating someone... nothing that marriage increases or guarantees.

Marriage doesn't save moments at all. It depends on the fact that you know someone only a little, that you don't work, that you're staying at a beautiful hotel near the Canal Grande, that you've had a beautiful evening at the Guggenheim Museum, that you've just eaten chocolate ice cream.

Marriage does not have the power to keep a relationship at this beautiful stage. He does not control the ingredients of our happiness at this point. In fact, marriage will resolutely move our relationship to a different, completely different point: suburban life, long interaction, two young children. The only thing in common is a partner. And it could be the wrong ingredient in that bottle.

Impressionist painters of the 19th century had a hidden philosophy of transience, pointing us in a wise direction. They accepted that happiness is transient as an inbuilt quality of existence, and could help increase reconciliation with it. Sisley’s painting depicting the French winter scene focuses on appealing but utterly elusive things. At sunset, the sun will disappear over the horizon. The glow of the sky for a short time makes branches bare branches less rigid. The snow is in quiet harmony with the gray wall; the cold seems calm, even exhilarating. It will be night in a few minutes.

Impressionism was interested in the fact that the things we love most are changeable, they only last for a short time, and then disappear. He notes a kind of happiness that lasts minutes rather than years. The snow in the picture looks nice, but it melts. At this point, the sky is beautiful, but it is about to darken. This style in art develops a skill that extends beyond art itself, the skill of accepting and paying attention to short moments of satisfaction.

The peak moments of life are short. Happiness does not come in the form of perennial blocks. Under the guidance of the Impressionists, we might be prepared to accept the individual moments of everyday paradise that come our way, without making the mistake that they are forever, without having to turn them into “marriage.”

Eighth, we think we're special.

The statistics are not encouraging. Everyone sees an example of terrible marriages. They see their friends trying and breaking up. We all know that marriages are difficult in general. We don’t apply this knowledge to ourselves so easily. Without specifically saying that, we assume that these are rules that apply to other people.

Even if the statistics say that the chance that a marriage will break up is one in two – it seems acceptable, especially if you are in love, it seems that the chances are much higher. A loved one feels like one in a million. And with such a winning combination, betting on marriage seems absolutely justified.

We silently exclude ourselves from generalizations. And nobody's accusing us of that. But we can benefit from seeing ourselves exposed to a common destiny.

Ninth: We want to stop thinking about love.

We probably had a few years of turbulence in our personal lives before we got married. We tried to be with people who didn’t like us, we started and broke alliances, we went to endless parties hoping to meet someone, experienced excitement and bitter disappointments.

It’s no wonder that at some point, that’s enough. Part of the reason we want to get married is to loosen the all-consuming grip of love on our souls. We are exhausted by melodramas and upheavals that lead nowhere. Other difficulties haunt us. We hope that marriage will end the painful rule of love in our lives.

It will not and cannot be: there are as many doubts, hopes, fears, rejection and betrayal in marriage as there are in solitary life. Only from the outside does marriage look peaceful, not rich in events and pleasantly boring.

Preparing for marriage is, ideally, an educational task that rests with culture as a whole. We stopped believing in dynastic marriage. We begin to see the disadvantages of a romantic marriage. It is time for psychological marriage.

Original English Thephilosophersmail.com

Source: /users/1077

How do these mistakes happen? So easy and regular, that's terrifying. It turns out that marrying the wrong person is one of the easiest and most expensive mistakes any one of us can make (and it puts a huge burden on the state, employers and the next generation), it goes beyond anything, it's almost criminal, that the issue of smart marriage is not a national and personal issue like traffic safety or smoking. And that's even sadder, because the truth is, the reasons why people make bad choices are easy to stand out and completely unsurprising at their core. It can be broken down into the following main categories. First, we don't understand ourselves.

When we first look for a partner, the demands we make are colored by a beautiful nonspecific sentimental ambiguity: we will say that we really want to find someone who is “kind” or “fun with,” who is “attractive” or “adventurous.”

Not that these are bad desires, they are just not even close enough to understand what we want in order for us to have a chance to be happy or, more precisely, not constantly unhappy.

We're all particularly crazy. We are certainly neurotic, unbalanced, and immature, but we don’t know the details, because no one has ever encouraged us to look for them. Thus, the urgent, the main task of any lover is to cope with the specific nuances of his own madness. They must become corresponding to their own neuroses. They need to understand where it came from, what made them so, and, most importantly, what kind of people provoke or comfort them. A good partnership is not between two healthy people (such are not on the planet), it is between two weak-minded people who are able or lucky to find a non-conscious agreement between two relative madnesses.

The idea that we may not be very complex as humans should be a wake-up call for any prospective partner. It's just a question of where the problems lie: maybe we have a hidden tendency to get angry when someone disagrees with us, or we can only relax when we work, or we're kind of uneasy about intimacy after sex, or we've never been good at explaining why we worry. These are the problems that, decades later, create catastrophes that we need to know about in advance in order to find people who are structurally optimal to withstand them. The standard question on any early date should be very simple: “What are you crazy about?”

The problem is that knowing our own neuroses is not easy. It can take years and take situations we've never been in. Before marriage, we rarely get involved in a dynamic that properly holds the mirror for our disorders. When a less serious relationship threatens to reveal the complexities of our nature, we tend to blame our partner and say it’s over. As for our friends, they predictably don't care so much about us to have any motive to explore the real us. They just want to have a good evening. We are blind to the weaknesses of our characters. By themselves, when we’re furious, we don’t scream if there’s no one to listen — and so we overlook our true, desperate power of rage. Or we work all the time without thinking, until no one invites us home for dinner — how maniacally we use work to gain a sense of control over life — and what hell can we do to anyone who tries to stop us? At night, all we feel is a desire to hug someone sweetly, but we do not have the opportunity to meet our avoiding intimacy side, which can make us cold and alien, even if we feel deeply committed to someone. One of the greatest privileges of being alone is the flattering illusion of being calm and comfortable.

With such a poor understanding of our character, it is not surprising that we cannot know who we are looking for.

Second, we don't understand other people.

This problem is complicated by the fact that other people are at the same low level of self-knowledge as we are. No matter how well-intentioned they are, they can't understand either, let alone tell us what's wrong with them.

Naturally, we throw test stones in an attempt to recognize them. We go and visit their families, sometimes places where they studied as children, we look at pictures, we meet with their friends. It all makes me feel like we've prepared. But it's kind of like a novice pilot would imagine he could fly after he'd run a paper airplane in a room.

In a wiser society, future partners will guide each other through detailed psychological testing and be sent for long evaluations by teams of psychologists. By 2100, this will no longer sound like a joke. It will be a mystery why humanity took so long.

We need to know the inner workings of the psyche of the person we want to marry. We need to know their attitudes and attitudes about power, humiliation, introspection, sexual intimacy, projections, money, children, aging, fidelity, and a hundred other things. This knowledge cannot be obtained in ordinary conversation.

In the absence of all that, we are most driven by what they look like. It seems that so much information can be gathered in what their eyes, nose, forehead shape, wrinkle distribution, smile... But it's like thinking that a picture of a nuclear plant outside can tell us everything we need to know about atom fission.

We project a series of perfections on loved ones based on very modest evidence. In the representation of the whole personality, out of small but memorable details, we do to the inner character of man what our sight does to the sketch of the face.

We don't see anyone in this picture without nostrils, with eight strands of hair and no eyelashes. We fill in the missing parts without noticing how we do it. Our brains are trained to take small visual cues and construct whole shapes out of them, and we do the same when it comes to the character of our future spouse. We pay dearly for the fact that, far more than we assume, we are artists very well refined reality.

The level of knowledge we need to process for marriage is higher than our society is willing to support, recognize, and reconcile—so our social practices around the family are deeply flawed.

Third, we are not used to being happy.

We believe we seek happiness in love, but it’s not that simple. What we’re really looking for is something that’s familiar — something that could complicate any happiness plans we have.

We recreate in adult relationships something from the feelings we learned as children. We were children when we first learned and understood what love meant. But unfortunately, the lessons we learned may not be so simple. The love we have learned as children may be woven with another, less pleasurable dynamic: being controlled, feeling humiliated, being abandoned, not communicating, suffering shorter.

As adults, we reject some of the healthy candidates we run into, not because they are wrong, but because they are too balanced (too mature, too understanding, too reliable), and this correctness looks unfamiliar and alien, even painful. Instead, we rush to those candidates that our unconscious reaches for, not because they will make us feel good, but because they will frustrate us in a familiar way.

We marry the wrong people because the right ones don't look that way -- undeservedly; because we don't have health experiences, because being loved completely isn't associated with a sense of contentment.

Fourth, being alone is so terrible.

If being alone is unbearable, then no one can be in the right state of consciousness to rationally choose a partner. We need to be absolutely at peace with the prospect of years of loneliness if we want to have a chance to form a good relationship. Or we like not to be alone more than we love a partner who fits us the way we are.

Unfortunately, society, after a certain age, makes loneliness dangerously unpleasant. Social life withers, couples feel threatened in the independence of singles to invite them too often, a person feels like a freak going alone to the movies. Sex is also hard to get. With all the new gadgets and supposed freedoms of modernity, it can be very difficult to end up in bed with someone, and waiting to do so regularly after 30 is associated with frustration.

It is much better to rebuild society on the principle of university or dormitory - with catering, common amenities, constant parties and sexual mixing. In this case, anyone who decides to marry will be sure to do so for reasons of the benefits of pairing rather than avoiding the negative side of loneliness.

When sex was only available in marriage at all, people realized that it led to marriage for the wrong reasons: to get something that was artificially restricted in society as such. People are free to make better choices about who to marry now that they're not just desperate for sex.

But in other areas, the deficit remains. When socializing in a company is only available to couples, then people will compose them just to rid themselves of loneliness. It is time to free “companionship” from the fetters of pairing, to make it as accessible as the freedom fighters wanted to make sex.

Fifth: The great prestige of instincts

In ancient times, marriage was a rational affair; it was all about connecting your piece of land with theirs. It was cold, ruthless and unrelated to the happiness of the protagonists. We're still traumatized by this.

We replaced marriage for reasons of instinct with romantic marriage. This dictates that the only way to get married is to feel for the other person. If someone feels like they are “loving,” that’s enough. No more questions. The feeling celebrated triumph. Others only applaud his appearance, respecting how the descent of the divine spirit can be respected. Parents may be horrified, but they must assume that only a couple knows the truth. We have had a collective reaction over the past three hundred years to thousands of years of ruthless intervention based on prejudice, snobbery and lack of imagination.

The previous “marriage of convenience” was so pedantic and prudent that one of the qualities of marriage from the senses seems that a person should not really think about why he is getting married. Analysis of the solution feels “unromantic.” Drawing tables for and against seems absurd and cold. The most romantic thing one can do is propose quickly and suddenly, perhaps within a week or a few, in a rush of enthusiasm - without any chance of making the terrible "reflections" that guaranteed sadness to people thousands of years before. The recklessness of the script is also a sign that marriage will be fine, precisely because the old type of “security” was a danger to happiness.

Sixth: We don't go to the School of Love

It is time for a third type of marriage. Psychological marriage. One in which one does not marry for the sake of the land, and not only because of “feeling”, but only when the “feeling” has been properly tested under the auspices of mature awareness of the psychology of oneself and of the other.

We are currently getting married without any information. We hardly read books on special topics, don’t spend more than a little time with our children, don’t question other married couples or speak sincerely to divorced couples. We go into this without any inner understanding of why the marriage breaks apart, except that we assume that the participants are stupid or lack of imagination.

In the era of marriage of convenience, the following criteria were considered:

- Who are their parents?

- how much land they have.

- how culturally close they are.

In the Romantic era, the following signs showed that everything was right.

You can’t stop thinking about your lover.

Have sexual passion

- Like each other.

- can communicate for a long time.

We need a new set of criteria. We need to know:

- what they're crazy about.

How they can raise children together

How can they develop together?

How can they remain friends?

Seventh: We want to freeze happiness.

We are doomed and desperate to insist on making pleasant things permanent. We want to have a car that we like, we want to live in a country that we like as tourists. And we want to get married to a person that we have an amazing time with.

We imagine that marriage is the guarantee of the happiness that we enjoy with someone. That he will make permanent what is otherwise fleeting. This will help us to catch the joy in the bottle - the joy we felt when the idea to propose first came to our mind: in Venice, in the lagoon, on a yacht, with the evening sun throwing golden glare all over the sea, the prospect of dinner in a small fish restaurant, with a loved one in a cashmere sweater in our arms ... We marry to make that feeling permanent.

Unfortunately, there is no causal relationship between marriage and these feelings. The feelings were about Venice, the time of year, the rest of work, the pleasure of dinner, two months of dating someone... nothing that marriage increases or guarantees.

Marriage doesn't save moments at all. It depends on the fact that you know someone only a little, that you don't work, that you're staying at a beautiful hotel near the Canal Grande, that you've had a beautiful evening at the Guggenheim Museum, that you've just eaten chocolate ice cream.

Marriage does not have the power to keep a relationship at this beautiful stage. He does not control the ingredients of our happiness at this point. In fact, marriage will resolutely move our relationship to a different, completely different point: suburban life, long interaction, two young children. The only thing in common is a partner. And it could be the wrong ingredient in that bottle.

Impressionist painters of the 19th century had a hidden philosophy of transience, pointing us in a wise direction. They accepted that happiness is transient as an inbuilt quality of existence, and could help increase reconciliation with it. Sisley’s painting depicting the French winter scene focuses on appealing but utterly elusive things. At sunset, the sun will disappear over the horizon. The glow of the sky for a short time makes branches bare branches less rigid. The snow is in quiet harmony with the gray wall; the cold seems calm, even exhilarating. It will be night in a few minutes.

Impressionism was interested in the fact that the things we love most are changeable, they only last for a short time, and then disappear. He notes a kind of happiness that lasts minutes rather than years. The snow in the picture looks nice, but it melts. At this point, the sky is beautiful, but it is about to darken. This style in art develops a skill that extends beyond art itself, the skill of accepting and paying attention to short moments of satisfaction.

The peak moments of life are short. Happiness does not come in the form of perennial blocks. Under the guidance of the Impressionists, we might be prepared to accept the individual moments of everyday paradise that come our way, without making the mistake that they are forever, without having to turn them into “marriage.”

Eighth, we think we're special.

The statistics are not encouraging. Everyone sees an example of terrible marriages. They see their friends trying and breaking up. We all know that marriages are difficult in general. We don’t apply this knowledge to ourselves so easily. Without specifically saying that, we assume that these are rules that apply to other people.

Even if the statistics say that the chance that a marriage will break up is one in two – it seems acceptable, especially if you are in love, it seems that the chances are much higher. A loved one feels like one in a million. And with such a winning combination, betting on marriage seems absolutely justified.

We silently exclude ourselves from generalizations. And nobody's accusing us of that. But we can benefit from seeing ourselves exposed to a common destiny.

Ninth: We want to stop thinking about love.

We probably had a few years of turbulence in our personal lives before we got married. We tried to be with people who didn’t like us, we started and broke alliances, we went to endless parties hoping to meet someone, experienced excitement and bitter disappointments.

It’s no wonder that at some point, that’s enough. Part of the reason we want to get married is to loosen the all-consuming grip of love on our souls. We are exhausted by melodramas and upheavals that lead nowhere. Other difficulties haunt us. We hope that marriage will end the painful rule of love in our lives.

It will not and cannot be: there are as many doubts, hopes, fears, rejection and betrayal in marriage as there are in solitary life. Only from the outside does marriage look peaceful, not rich in events and pleasantly boring.

Preparing for marriage is, ideally, an educational task that rests with culture as a whole. We stopped believing in dynastic marriage. We begin to see the disadvantages of a romantic marriage. It is time for psychological marriage.

Original English Thephilosophersmail.com

Source: /users/1077