330

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 6 (final)

Google is different. Google is looking to the future. Google has a future. Google is more than just a company. Google is paying tribute to society. Google is a force for good.

Even when Google showed its corporate ambivalence to the public, it didn’t do much to dent trust in the company. Her reputation seems unshakable. Google’s colorful, playful logo is imprinted on the human eye a little less than six billion times every day, 2.1 trillion times a year – an opportunity for processing that no company in history has had.

Caught by the hand of petabytes of personal data leaked to government intelligence under the PRISM program last year, Google has nonetheless continued effortlessly to keep up with its “don’t be evil” demagoguery.

A few symbolic open letters to the White House, and all seems forgiven. Even anti-surveillance campaigners can’t help themselves by denouncing government espionage and temporarily trying to change Google’s aggressive surveillance practices by using the peacemaker’s strategy.

No one wants to admit that Google has grown big and bad. But it is. During his tenure as CEO at Google, Eric Schmidt managed to integrate the company with shadowy U.S. government structures as it grew into a geographically aggressive megacorporation.

However, Google has always been comfortable with this closeness. Long before Larry Page and Sergey Brin hired Schmidt in 2001, their initial research on which Google was founded was partly funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Thank you" description of the student project of the search engine from 1998.

And even as Google acquired the image of an overly friendly tech giant under Schmidt, it was building close ties with the intelligence community.

By 2013, the NSA had systematically violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) under General Michael Hayden. These were days of “total information awareness.” Total Information Awareness, a radical program to spy on individuals for their possible behavior, was launched after September 11 under DARPA. Although it was shut down in 2003 in connection with protests, its foundation could serve as a basis for future mass surveillance of the NSA.

Before the PRISM program was even conceived, at the behest of the Bush White House, the NSA was ready to “gather, sniff, learn, process and use everything.”

In the same time period, Google, which declared its corporate mission to collect and “order all the world’s information, making it publicly available and useful,” accepts payments from the NSA worth $ 2 million for providing the Agency with search tools to quickly process the database of stolen knowledge.

In 2004, Google acquired Keyhole, a mapping startup founded by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the CIA. On its basis, the Google Earth program was created, the enterprise version of which Google sold to the Pentagon, and also received millions of contracts from federal and state agencies.

In 2008, with the support of Google, the first NGA space satellite called GeoEye-1 was launched, images from which the company shared with the US military and intelligence. In 2010, the NGA awarded Google a $27 million “geospatial services visualization” contract.

In 2010, when the Chinese government was accused of hacking Google, the company entered into a relationship of “formal information sharing” with the NSA, which allowed analysts to make a “vulnerability assessment” of Google’s software and hardware. Although the terms of the deal were not disclosed, the NSA has invited other agencies, including the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, to help.

Around the same time, Google began participating in a program called the Enduring Security Framework (ESF), which created a network of rapid information sharing between Silicon Valley companies and Pentagon affiliates.

Emails obtained in 2014 show that Schmidt and Sergey Brin are freely communicating with General Keith Alexander, the head of the NSA, about the ESF program. In the investigation of the letters received, the emphasis is on familiarity in the correspondence between these people. “General Keith...so great to see you...!” wrote Schmidt. But most correspondence reports miss a key detail. “Your ideas as a key member of the defense industrial base,” Alexander wrote to Brin, “are of great value because they provide a tangible return to the ESF program.”

The Department of State Security defines a defense industrial base as “a worldwide manufacturing facility that enables research and development, as well as the design, production, delivery, and support of military weapons systems, subsystems, and parts and components to meet U.S. military requirements.”

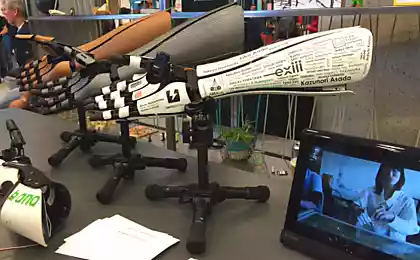

Screenshot from Eric Schmidt's Instagram video on May 2, 2014, showing the work of one of the first versions of the famous robots of Boston Dynamics, which Google, according to the latest news, sells.

The defense industrial base provides "products and services that are essential to mobilizing, deploying and supporting military operations." Does this include regular commercial services provided to the U.S. military? Nope. The definition specifically excludes the purchase of commercial services. Whatever makes Google a “key member of the defense industry base,” it’s not Google AdWords campaigns or Gmail checks for soldiers.

In 2012, Google was included in the list of top spenders on the lobby in Washington, usually on this list only the US Chamber of Commerce, military contractors and hydrocarbon leviathan. Google ranked above military space giant Lockheed Martin, spending $18.2 million, compared to Lockheed Martin’s $15.3 million.

Boeing, the military contractor that acquired McDonnell Douglas in 1997, was also lower at $15.6 million. Northrop Grumman Corporation, an American military-industrial company operating in the fields of electronics and information technology, aerospace, shipbuilding, was also lower, spending $ 17.5 million.

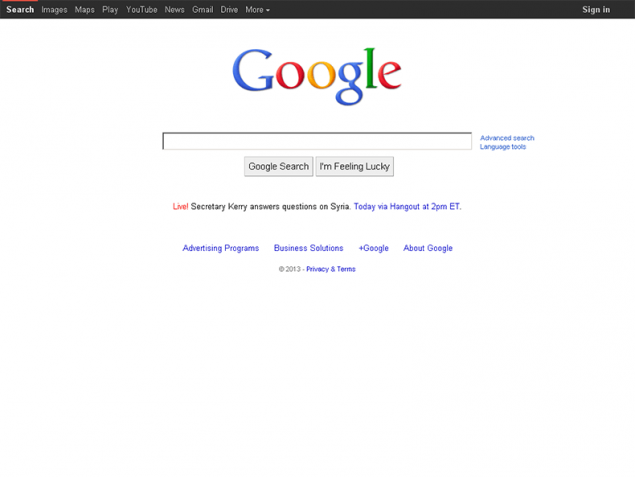

In the fall of 2013, the Obama administration sought approval for airstrikes in Syria. Despite the setbacks, the administration continued to push for military action in September in speeches and public appearances by President Barack Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry.

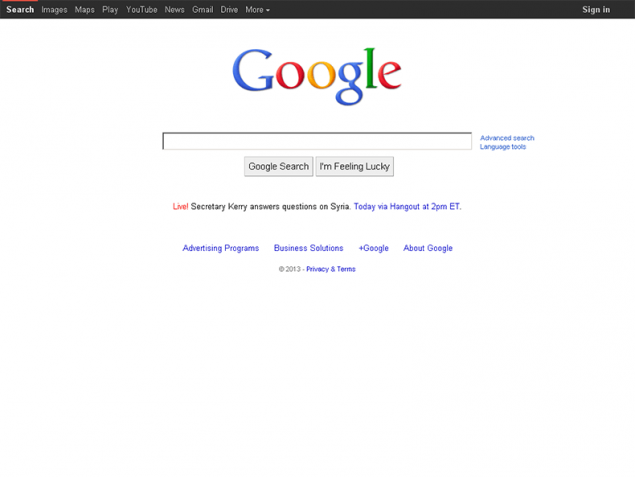

On September 10, Google lent its homepage, the most popular page on the Internet, to support the war by posting a search for “Live!” Secretary Kerry answers questions on Syria. Live! Secretary Kerry answers questions on Syria. Today via Hangout at 2pm ET. Assange notes that among other things, this case violates the first of 10 corporate “commandments”. The interface of our homepage is simple and clear, and pages load instantly. Places in search results are not sold to anyone, advertising is always marked as such and filled with relevant content so as not to distract.”

Google Homepage September 10, 2013

The New York Times columnist, and what he calls himself a “radical centrist,” Tom Friedman, in 1999 described the relationship between American tech companies and the government as something akin to a “free market”:

“The invisible hand of the market will never work without the invisible fist. McDonnell cannot thrive without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps Silicon Valley’s thriving tech world safe is called the U.S. Army and Marine Corps.

And if anything has changed since these words were written, it is that the Valley has grown out of its passive role and is trying to tame this “invisible fist” by becoming something of a velvet glove to it. In 2013, Schmidt and Cohen stated:

“What Lockheed Martin was to the twentieth century, technology and information security companies will be to the twenty-first.”

This is just one of many bold assertions made by Schmidt and Cohen in their book, which was eventually published in April 2013. “The Empire of Mind” has been changed to “The New Digital Age: Changing the Future of People, Nations and Business.”

By the time it was released, I had sought and received political asylum from the Ecuadorian government and had taken refuge in their embassy in London. At the time, I had spent a year in their embassy under police surveillance blocking safe passage from the United Kingdom.

Already online, I noticed the buzz of the press reacting to the book, flippantly ignoring digital imperialism in the title, and pre-publication praise from famous warmongers like Tony Blair, Henry Kissinger, Bill Hayden, and Madeleine Albright.

Eric Schmidt and Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State and head of the National Security Council under Richard Nixon, during a “relaxed chatter” meeting with employees at Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California, on September 30, 2013.

Announced as a far-sighted forecast of the scientific and technological future, the book is not fulfilling its purpose. We cannot even imagine a future, good or bad, that is different from the present. This book is a simplified fusion of the ideology of the “end of history” Fukuyama – fashionable in the 90s – and fast mobile phones.

It is smeared with tattered D.C. slogans, State Department orthodoxy, and flattering flirtations with Henry Kissinger. The content is low – even unprofitable. It didn't seem to fit the profile of Schmidt, that sharp, quiet man in my living room. But as I read it, I began to realize that this book was not a serious attempt to look into the future. It was a love song from Google to Washington. Google, a burgeoning digital superpower, offers Washington a geopolitical vision.

On the one hand, it's just business. It’s not enough for America’s Internet services to have a monopoly of global influence to just keep doing what they’ve been doing and let politicians take care of themselves. American strategic and economic dominance is becoming a critical pillar for these companies in their own dominant market position. What do mega-corporations do? If it wants to ride the world, it must become part of the original “don’t be evil” empire.

But part of Google's cheerful image as "more than just a company" comes from a sense that this company can't be anything big and vicious. Its penchant for luring people into its traps of gigabytes of “free storage” gives the impression that Google is giving out services for free, acting against corporate utility considerations.

Google is seen as a purely charitable enterprise – a magical engine driven by mysterious dreamers – leading to a utopian future. At times, the company begins to cultivate this image anxiously, infusing finance into “corporate responsibility” initiatives to produce “social change” – as Google Ideas exemplifies.

But Google Ideas shows that the company’s “charitable” efforts also bring an awkward affinity to the imperialist side of American influence. If Blackwater/Xe Services/Academi launches a program like Google Ideas, there will be a flurry of criticism. But for some reason, Google is open.

[note] Note: Utopianism often borders on megalomania. For example, Larry Page has spoken publicly about his vision of Google microstates like Jurassic Park: “Laws ... they can’t be right if they’re 50 years old; they predate the Internet.” [...] Could we separate a piece of the world and create an environment where people can do something new? I think we as technologists need to have a safe place to do new things and learn how they will affect society, what impact they will have on people, without having to deploy globally. ?

Whether Google is just a company or “more than just a company,” its political aspirations are woven into the foreign policy agenda of the world’s largest superpower. As Google’s monopoly of search and other Internet services grows, as production surveillance covers an increasing population of the planet, the fast-growing mobile market and the race to cover the world with the Web are making Google synonymous with the word “internet” for more people. A company’s ability to influence a person’s choices and behavior gives it the power to influence the course of history.

If the future of the Internet is to become Google, it is a cause for concern for people around the world – in Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, equatorial Africa, the former Soviet Union, and even Europe – for all those for whom the Internet embodies the hope of an alternative to American culture, economy, and strategic dominance.

The empire of good remains an empire. published

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox Part 1

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 2

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 3

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 4

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 5

P.S. And remember, just changing our consumption – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: megamozg.ru/post/25078/

Even when Google showed its corporate ambivalence to the public, it didn’t do much to dent trust in the company. Her reputation seems unshakable. Google’s colorful, playful logo is imprinted on the human eye a little less than six billion times every day, 2.1 trillion times a year – an opportunity for processing that no company in history has had.

Caught by the hand of petabytes of personal data leaked to government intelligence under the PRISM program last year, Google has nonetheless continued effortlessly to keep up with its “don’t be evil” demagoguery.

A few symbolic open letters to the White House, and all seems forgiven. Even anti-surveillance campaigners can’t help themselves by denouncing government espionage and temporarily trying to change Google’s aggressive surveillance practices by using the peacemaker’s strategy.

No one wants to admit that Google has grown big and bad. But it is. During his tenure as CEO at Google, Eric Schmidt managed to integrate the company with shadowy U.S. government structures as it grew into a geographically aggressive megacorporation.

However, Google has always been comfortable with this closeness. Long before Larry Page and Sergey Brin hired Schmidt in 2001, their initial research on which Google was founded was partly funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Thank you" description of the student project of the search engine from 1998.

And even as Google acquired the image of an overly friendly tech giant under Schmidt, it was building close ties with the intelligence community.

By 2013, the NSA had systematically violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) under General Michael Hayden. These were days of “total information awareness.” Total Information Awareness, a radical program to spy on individuals for their possible behavior, was launched after September 11 under DARPA. Although it was shut down in 2003 in connection with protests, its foundation could serve as a basis for future mass surveillance of the NSA.

Before the PRISM program was even conceived, at the behest of the Bush White House, the NSA was ready to “gather, sniff, learn, process and use everything.”

In the same time period, Google, which declared its corporate mission to collect and “order all the world’s information, making it publicly available and useful,” accepts payments from the NSA worth $ 2 million for providing the Agency with search tools to quickly process the database of stolen knowledge.

In 2004, Google acquired Keyhole, a mapping startup founded by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the CIA. On its basis, the Google Earth program was created, the enterprise version of which Google sold to the Pentagon, and also received millions of contracts from federal and state agencies.

In 2008, with the support of Google, the first NGA space satellite called GeoEye-1 was launched, images from which the company shared with the US military and intelligence. In 2010, the NGA awarded Google a $27 million “geospatial services visualization” contract.

In 2010, when the Chinese government was accused of hacking Google, the company entered into a relationship of “formal information sharing” with the NSA, which allowed analysts to make a “vulnerability assessment” of Google’s software and hardware. Although the terms of the deal were not disclosed, the NSA has invited other agencies, including the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, to help.

Around the same time, Google began participating in a program called the Enduring Security Framework (ESF), which created a network of rapid information sharing between Silicon Valley companies and Pentagon affiliates.

Emails obtained in 2014 show that Schmidt and Sergey Brin are freely communicating with General Keith Alexander, the head of the NSA, about the ESF program. In the investigation of the letters received, the emphasis is on familiarity in the correspondence between these people. “General Keith...so great to see you...!” wrote Schmidt. But most correspondence reports miss a key detail. “Your ideas as a key member of the defense industrial base,” Alexander wrote to Brin, “are of great value because they provide a tangible return to the ESF program.”

The Department of State Security defines a defense industrial base as “a worldwide manufacturing facility that enables research and development, as well as the design, production, delivery, and support of military weapons systems, subsystems, and parts and components to meet U.S. military requirements.”

Screenshot from Eric Schmidt's Instagram video on May 2, 2014, showing the work of one of the first versions of the famous robots of Boston Dynamics, which Google, according to the latest news, sells.

The defense industrial base provides "products and services that are essential to mobilizing, deploying and supporting military operations." Does this include regular commercial services provided to the U.S. military? Nope. The definition specifically excludes the purchase of commercial services. Whatever makes Google a “key member of the defense industry base,” it’s not Google AdWords campaigns or Gmail checks for soldiers.

In 2012, Google was included in the list of top spenders on the lobby in Washington, usually on this list only the US Chamber of Commerce, military contractors and hydrocarbon leviathan. Google ranked above military space giant Lockheed Martin, spending $18.2 million, compared to Lockheed Martin’s $15.3 million.

Boeing, the military contractor that acquired McDonnell Douglas in 1997, was also lower at $15.6 million. Northrop Grumman Corporation, an American military-industrial company operating in the fields of electronics and information technology, aerospace, shipbuilding, was also lower, spending $ 17.5 million.

In the fall of 2013, the Obama administration sought approval for airstrikes in Syria. Despite the setbacks, the administration continued to push for military action in September in speeches and public appearances by President Barack Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry.

On September 10, Google lent its homepage, the most popular page on the Internet, to support the war by posting a search for “Live!” Secretary Kerry answers questions on Syria. Live! Secretary Kerry answers questions on Syria. Today via Hangout at 2pm ET. Assange notes that among other things, this case violates the first of 10 corporate “commandments”. The interface of our homepage is simple and clear, and pages load instantly. Places in search results are not sold to anyone, advertising is always marked as such and filled with relevant content so as not to distract.”

Google Homepage September 10, 2013

The New York Times columnist, and what he calls himself a “radical centrist,” Tom Friedman, in 1999 described the relationship between American tech companies and the government as something akin to a “free market”:

“The invisible hand of the market will never work without the invisible fist. McDonnell cannot thrive without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps Silicon Valley’s thriving tech world safe is called the U.S. Army and Marine Corps.

And if anything has changed since these words were written, it is that the Valley has grown out of its passive role and is trying to tame this “invisible fist” by becoming something of a velvet glove to it. In 2013, Schmidt and Cohen stated:

“What Lockheed Martin was to the twentieth century, technology and information security companies will be to the twenty-first.”

This is just one of many bold assertions made by Schmidt and Cohen in their book, which was eventually published in April 2013. “The Empire of Mind” has been changed to “The New Digital Age: Changing the Future of People, Nations and Business.”

By the time it was released, I had sought and received political asylum from the Ecuadorian government and had taken refuge in their embassy in London. At the time, I had spent a year in their embassy under police surveillance blocking safe passage from the United Kingdom.

Already online, I noticed the buzz of the press reacting to the book, flippantly ignoring digital imperialism in the title, and pre-publication praise from famous warmongers like Tony Blair, Henry Kissinger, Bill Hayden, and Madeleine Albright.

Eric Schmidt and Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State and head of the National Security Council under Richard Nixon, during a “relaxed chatter” meeting with employees at Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California, on September 30, 2013.

Announced as a far-sighted forecast of the scientific and technological future, the book is not fulfilling its purpose. We cannot even imagine a future, good or bad, that is different from the present. This book is a simplified fusion of the ideology of the “end of history” Fukuyama – fashionable in the 90s – and fast mobile phones.

It is smeared with tattered D.C. slogans, State Department orthodoxy, and flattering flirtations with Henry Kissinger. The content is low – even unprofitable. It didn't seem to fit the profile of Schmidt, that sharp, quiet man in my living room. But as I read it, I began to realize that this book was not a serious attempt to look into the future. It was a love song from Google to Washington. Google, a burgeoning digital superpower, offers Washington a geopolitical vision.

On the one hand, it's just business. It’s not enough for America’s Internet services to have a monopoly of global influence to just keep doing what they’ve been doing and let politicians take care of themselves. American strategic and economic dominance is becoming a critical pillar for these companies in their own dominant market position. What do mega-corporations do? If it wants to ride the world, it must become part of the original “don’t be evil” empire.

But part of Google's cheerful image as "more than just a company" comes from a sense that this company can't be anything big and vicious. Its penchant for luring people into its traps of gigabytes of “free storage” gives the impression that Google is giving out services for free, acting against corporate utility considerations.

Google is seen as a purely charitable enterprise – a magical engine driven by mysterious dreamers – leading to a utopian future. At times, the company begins to cultivate this image anxiously, infusing finance into “corporate responsibility” initiatives to produce “social change” – as Google Ideas exemplifies.

But Google Ideas shows that the company’s “charitable” efforts also bring an awkward affinity to the imperialist side of American influence. If Blackwater/Xe Services/Academi launches a program like Google Ideas, there will be a flurry of criticism. But for some reason, Google is open.

[note] Note: Utopianism often borders on megalomania. For example, Larry Page has spoken publicly about his vision of Google microstates like Jurassic Park: “Laws ... they can’t be right if they’re 50 years old; they predate the Internet.” [...] Could we separate a piece of the world and create an environment where people can do something new? I think we as technologists need to have a safe place to do new things and learn how they will affect society, what impact they will have on people, without having to deploy globally. ?

Whether Google is just a company or “more than just a company,” its political aspirations are woven into the foreign policy agenda of the world’s largest superpower. As Google’s monopoly of search and other Internet services grows, as production surveillance covers an increasing population of the planet, the fast-growing mobile market and the race to cover the world with the Web are making Google synonymous with the word “internet” for more people. A company’s ability to influence a person’s choices and behavior gives it the power to influence the course of history.

If the future of the Internet is to become Google, it is a cause for concern for people around the world – in Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, equatorial Africa, the former Soviet Union, and even Europe – for all those for whom the Internet embodies the hope of an alternative to American culture, economy, and strategic dominance.

The empire of good remains an empire. published

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox Part 1

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 2

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 3

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 4

Julian Assange: Google is not what it seems from the sandbox. Part 5

P.S. And remember, just changing our consumption – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: megamozg.ru/post/25078/