590

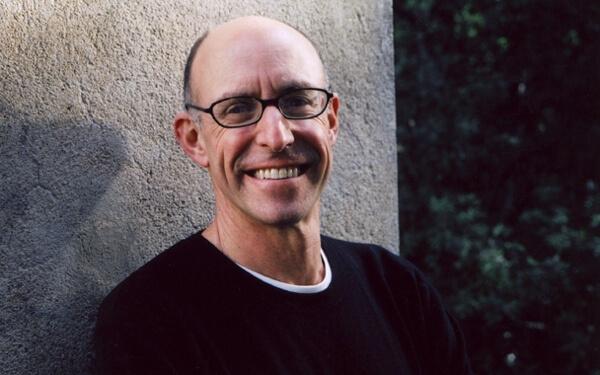

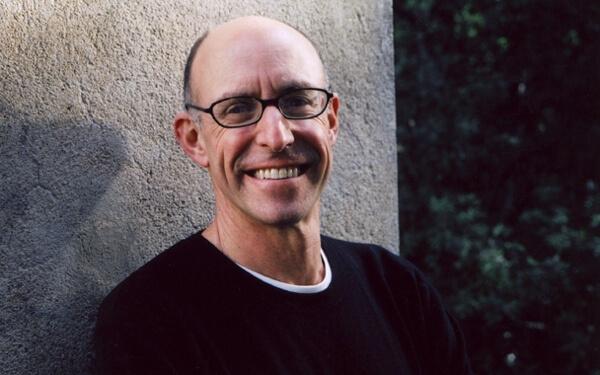

Addictive licciana TED Michael Pollan: look at the world from the point of view of plants

What if human consciousness is not the pinnacle of Darwinism? What if we are all nothing more than pawns in a cunning strategic plan for the corn to take over the world? Author Michael Pollan asks us to see the world from the point of view of plants.

0:11

Here is a simple idea about nature. I want to say a word on behalf of nature, because we talked a lot about it the last couple of days. I want to say a word for the earth, for bees, plants and animals, and to tell you about a tool, a very simple tool that I have found. Although, in fact, is nothing more than a literary device, it is not the technology. He is very strong, I think, to change our relationship to the natural world and other species on which we depend. And this tool is, quite simply, as Chris said, look on us and the world from the point of view of plants or animals. It's not my idea, other people have seen her around, but I tried to push it into some new areas.

https://embed.ted.com/talks/lang/ru/michael_pollan_gives_a_plant_s_eye_view

0:57

Let me tell you where I found it. Like many ideas, many of the tools that I use, I found her in the garden. I am a very keen gardener. One day, about seven years ago, I planted potatoes. It was in the first week of may in New England, when the Apple trees were blooming and were similar to white clouds. I've been here, cut a potato into pieces and planted them, and the bees worked on the tree; that bumblebees have created such a vibration.

1:29

What I really like about gardening is the fact that it does not require full concentration, you can't get hurt, unlike the woodwork, and you have a lot of mental space for reflection. The question that I asked myself that day in the garden, working alongside that bumblebee was: I have that bumblebee have in common? As far as our roles in the garden is similar and how different? And I realized that actually we have quite a lot in common: we are both engaged in the spread of genes of one species and not another, and both of us probably, if I can imagine the bee's point of view, thought we were in control of the situation. I decided what kind of potatoes I want to plant, I chose Yukon gold or yellow Finn or some other, and I summoned those genes from a seed catalog the other end of the country, brought and planted them. And bee certainly thought she decided: "I'm flying to the Apple tree, I'm going to that flower, I collect the nectar and fly away."

2:36

We have a grammar, which implies that we are that we are independent agents in nature, and bumblebee and me. I'm planting potatoes, the field I garden, I learn of the variety. But that day it occurred to me: what if that grammar is nothing more than vanity? Because, of course, the bee thinks that he or she makes decisions, but we know better. We know that what happens between the bee and the flower, that bee is skillfully manipulated by the flower. And when I say it's rigged, I mean in the Darwinian sense. I mean that the flower has acquired in the evolution of very specific features — color, smell, taste, appearance — which attracted this bee. And the bee cleverly fooled, forcing him to gather nectar and pick up pollen by the leg and fly to the next flower. The bee does not control the situation. And then I realized that I had too.

3:36

I was tempted by the fries, but not the other, so I put her in spreading her genes and giving her a little more living space. And then I came up with this idea: "what if we look at ourselves from the point of view of these other species that we work on?" And agriculture suddenly appeared to me not an invention, not a human technology, and co-evolutionary development in which a group of very cunning creatures, mostly edible grasses, had exploited us, figured out how to make us, essentially, to obelezite the world. To take out the competition of grasses, right? And suddenly everything began to look different. And suddenly mowing the lawn that day felt very different.

4:18

I have always believed, and even wrote about it in his first book — it was a book about gardening — the lawn is nature under the Shoe culture that they are totalitarian landscapes, and when we mow them, we brutally suppressed these species, not allowing them to plant a seed or die or have sex. And it has a lawn. But then I realized, "No, this is exactly what herbs you want us to do. I'm a pushover. I deceived lawns, whose goal in life is to defeat the trees with which they compete for sunlight." So when we are forced to mow the lawn, we hold against the return of the trees in New England are growing very quickly.

5:00

I began to look at things this way and wrote about a book called "Botany of desire". And I thought that as well as you can see on the flower and make interesting insights about the tastes and desires of bees — that they like sweets, they love this color, not the one that they like symmetry — what could learn about ourselves the same way? That a certain kind of potato, a certain type of drug, the hybrid seed and Indian hemp, may of us something to say. However it's a fun way to see the world?

5:37

Now, check any ideas — I said that this literary ploy is that it gives us? And when you talk about nature, which is actually my subject as a writer is how she meets the test of Aldo Leopold? Namely, if it makes us better citizens of the society of flora and fauna? Forcing us to do things that support and perpetuate wildlife, instead of destroying it? And I would argue that this idea does it. So let me explain what benefits you get when you look at the world thus, in addition to some fun discoveries about human desires.

6:13

On an intellectual level, look at the world from the point of view of other species helps us to cope with the strange anomaly, namely, and that from the sphere of intellectual history — namely, that we have the Darwinian revolution 150 years ago... Oh, mini-me. (Laughter) we Have this intellectual revolution of Darwin in which, thanks to Darwin, we realized that we are just one species out of many; evolution is working on us the same way as it works on all the others, we act and not only we are acting; we are really in the fiber, in the fabric of life. But the strange thing is that we have not learned this lesson over 150 years; none of us truly believes it. We are still Cartesians — the children of Descartes-who believe that subjectivity and consciousness separates us, that the world is divided into subjects and objects that is the nature on the one hand and culture on the other. As you begin to look at things from the point of view of plants or animals, you realize that this literary ploy is the idea that nature is the opposite culture of what consciousness is most important. And this is another very important lesson.

7:37

Look at the world from the point of view of other species is a cure for the plague of human vanity. Once you understand that consciousness, which we appreciate and believe in the highest achievement of nature, human consciousness — is really just another set of tools to survive in this world. And it is quite natural that we think this is the best tool. But, you know, is a humorist, who said: "And who tells me that consciousness is so good and important? Consciousness itself". And when you look at the plants, you realize that there are other tools that are just as interesting.

8:18

I'll give you two examples, also from the garden: Lima beans. You know that the Lima bean does when it is attacked spider mites? It releases a volatile chemical, which spreads and attracts the mites of other species that come and attack the spider mite, defending the beans. That is, the plants — while we have consciousness, tool-making, language, they have biochemistry. And they have perfected it to such an extent that we cannot imagine. Their complexity and sophistication worthy of admiration, and I think that this is actually the scandal of the human genome project. You know, we started recommending 40,000 or 50,000 human genes, and was only 23,000. To give you a grounds for comparison, rice 35 000 genes. So who's more advanced? We are all equally advanced. We evolved during the same time, just in different ways. Here, the cure of vanity, a way to feel the idea of Darwin. And that's what I do as a writer, like a storyteller, trying to get people to feel what we know and tell stories which help us think ecologically.

9:43

Now, another use of this practice. I will lead you now to the farm, because I used this idea to develop their understanding of the food system, and I found out that all of us are now manipulated corn. The report about ethanol, which you heard earlier today, for me it is the final triumph of corn over common sense. (Laughter) (Applause) That's part of the plan of corn to take over the world. (Laughter) And you will see the amount of corn planted this year will be much higher than in the past, and it will be so much more given space, because we decided that ethanol will be fruitful for us.

10:23

So it helped me understand industrial agriculture, which of course is a Cartesian system. It is based on the idea that we subjugate the other species to our will and that we are important, that we create a factory and includes such technological things, and out for food or fuel or whatever we want. Let me show you a very different type of farm.

10:43

Is a farm in the valley of Sananda in Virginia. I was looking for a farm that would use the idea of looking at things from the point of view of the species, and I found this in man. The name of this farmer Joel Salatin. I spent a week as an apprentice on his farm and collected enough encouraging facts about our relationship with nature, the stronger of which I have not seen in 25 years that I write about nature. And they are this: it's called Politas that means... the Idea that he's got six different species of animals and also some plants grow in a very thoroughly developed a symbiotic manner.

11:18

This is permaculture, if you know a little about it, is that cows, pigs, sheep, turkeys, and -- what else he's got? All six types — and, even bunnies, all provide ecological services to each other, so that the manure from one lunch to another, and they save each other from parasites. This is a very complex and beautiful dance, but I'll get to only one piece and it's relationship between his cows and his chickens-laying hens. I'll show you what happens if you follow this approach. And it is much more than growing food, as you will see. This is another way to think about nature and a way to get away from the concept of zero sum, the Cartesian idea that either nature's winning or we're winning, and that if we get what we want, the nature will decrease.

12:12

Then, one day, cows in the paddock. The only technology that is used here is this cheap electric fence: fairly new, connected to the car battery. Even I could move the fence on 10 acres and install it in 15 minutes. Cows graze one day. They move, right? They all eat up, intensive grazing. He waits three days, and then we bring something called Aitios. Allawos this is a very shaky structure he looks like a wooden schooner, but he lives 350 chickens. He brings it to the site three days later, opens the door, turns them down, and 350 hens come down the stairs, clucking and bubbling as usual and headed directly to the cow patties.

12:59

And what they do is very interesting: they are poking around cow pies looking for fly larvae. He waited three days, because he knows that on the fourth or fifth day, those larvae will hatch and will have a huge problem with flies. But he waits so long to grow them as much as possible, juicier and tastier, since chicken is a favorite protein.

13:25

So the chickens do their little dance and they push the manure to get the larvae, and in the process they distribute on the ground. The second very useful ecosystem. And third, while they're on this site, of course, they poop a lot and their very nitrogenous manure is fertilizing the field. They then move to another area, and just a few weeks, the grass there is a flash of growth. And after four or five weeks he can repeat. He can graze again, he can mow the grass, it may bring other animals, such as sheep, or can procure hay for the winter.

14:10

Now, I want you to look closely at what happened here. It is a very productive system. And I need to tell you that on a few hectares he grows 10 tons of beef, 10 tonnes of pork, 300 000 eggs, 20,000 chickens, 1,000 turkeys, 1,000 rabbits huge amount of food.

14:27

Know asked: "Can organic food feed the world?" Let's see how much food can be produced on several hectares if you do so... again, give each species what it wants, give him realize their desires, their physiological individuality. Apply this on the case.

14:43

And now look at it from the point of view of grass. What happens to grass if you do? When the ruminant animal eats grass, the grass is cut from this length to this length, and it immediately does something very interesting. For those of you who has been gardening, you know that there are so-called the ratio of the mass of roots and shoots, and what plants need to keep the root mass in rough balance with the mass of foliage, to feel good. So when they lose a lot of leaf mass, they swing the roots; they are as it were burned, and the roots die. And animals in the land to work, chewing those roots, decomposing them — earthworms, fungi, bacteria — and the result is new soil. This creates a soil. It is created from the bottom up. This is how arose the Prairie the interaction of bison and herbs.

15:36

And that's what I understood when I realized it, and if you ask Joel Salatin who he is, he will say that he is not a farmer's chickens or sheep or cows — he is a farmer growing grass, because grass is really the basis for this system. If you think about it, this completely contradicts the tragic idea of nature we hold in our head, that we get what we want, the nature will decrease. The more we are, the less nature. Here, all this food comes off this farm, and at the end of the season there is more soil, more fertility and more biodiversity.

16:21

This is a very encouraging lesson. Now there are many farmers engaged in this. This greatly beyond organic agriculture, which is still a Cartesian system, more or less. It says that if you start to consider other views, to consider the ground that with such a promising idea, since there is no technology, except for those fences, which are so cheap that they can instantly appear all over Africa, we can take the required food from the Land and also the Land to heal.

"Who we really are?": the best selection of TED lectures of scientists and philosophers ofthe Ideology of TED Chris Anderson: why be able to speak every needs

17:03

It's a way to revive the world, and why this view is so exciting. When we bones are inspired by Darwin's discoveries, things that we can do using nothing more than these ideas are very encouraging.

17:18

Thank you very much.published

Put LIKES and share with your FRIENDS!

www.youtube.com/channel/UCXd71u0w04qcwk32c8kY2BA/videos

Source: www.ted.com/talks/michael_pollan_gives_a_plant_s_eye_view?language=ru

0:11

Here is a simple idea about nature. I want to say a word on behalf of nature, because we talked a lot about it the last couple of days. I want to say a word for the earth, for bees, plants and animals, and to tell you about a tool, a very simple tool that I have found. Although, in fact, is nothing more than a literary device, it is not the technology. He is very strong, I think, to change our relationship to the natural world and other species on which we depend. And this tool is, quite simply, as Chris said, look on us and the world from the point of view of plants or animals. It's not my idea, other people have seen her around, but I tried to push it into some new areas.

https://embed.ted.com/talks/lang/ru/michael_pollan_gives_a_plant_s_eye_view

0:57

Let me tell you where I found it. Like many ideas, many of the tools that I use, I found her in the garden. I am a very keen gardener. One day, about seven years ago, I planted potatoes. It was in the first week of may in New England, when the Apple trees were blooming and were similar to white clouds. I've been here, cut a potato into pieces and planted them, and the bees worked on the tree; that bumblebees have created such a vibration.

1:29

What I really like about gardening is the fact that it does not require full concentration, you can't get hurt, unlike the woodwork, and you have a lot of mental space for reflection. The question that I asked myself that day in the garden, working alongside that bumblebee was: I have that bumblebee have in common? As far as our roles in the garden is similar and how different? And I realized that actually we have quite a lot in common: we are both engaged in the spread of genes of one species and not another, and both of us probably, if I can imagine the bee's point of view, thought we were in control of the situation. I decided what kind of potatoes I want to plant, I chose Yukon gold or yellow Finn or some other, and I summoned those genes from a seed catalog the other end of the country, brought and planted them. And bee certainly thought she decided: "I'm flying to the Apple tree, I'm going to that flower, I collect the nectar and fly away."

2:36

We have a grammar, which implies that we are that we are independent agents in nature, and bumblebee and me. I'm planting potatoes, the field I garden, I learn of the variety. But that day it occurred to me: what if that grammar is nothing more than vanity? Because, of course, the bee thinks that he or she makes decisions, but we know better. We know that what happens between the bee and the flower, that bee is skillfully manipulated by the flower. And when I say it's rigged, I mean in the Darwinian sense. I mean that the flower has acquired in the evolution of very specific features — color, smell, taste, appearance — which attracted this bee. And the bee cleverly fooled, forcing him to gather nectar and pick up pollen by the leg and fly to the next flower. The bee does not control the situation. And then I realized that I had too.

3:36

I was tempted by the fries, but not the other, so I put her in spreading her genes and giving her a little more living space. And then I came up with this idea: "what if we look at ourselves from the point of view of these other species that we work on?" And agriculture suddenly appeared to me not an invention, not a human technology, and co-evolutionary development in which a group of very cunning creatures, mostly edible grasses, had exploited us, figured out how to make us, essentially, to obelezite the world. To take out the competition of grasses, right? And suddenly everything began to look different. And suddenly mowing the lawn that day felt very different.

4:18

I have always believed, and even wrote about it in his first book — it was a book about gardening — the lawn is nature under the Shoe culture that they are totalitarian landscapes, and when we mow them, we brutally suppressed these species, not allowing them to plant a seed or die or have sex. And it has a lawn. But then I realized, "No, this is exactly what herbs you want us to do. I'm a pushover. I deceived lawns, whose goal in life is to defeat the trees with which they compete for sunlight." So when we are forced to mow the lawn, we hold against the return of the trees in New England are growing very quickly.

5:00

I began to look at things this way and wrote about a book called "Botany of desire". And I thought that as well as you can see on the flower and make interesting insights about the tastes and desires of bees — that they like sweets, they love this color, not the one that they like symmetry — what could learn about ourselves the same way? That a certain kind of potato, a certain type of drug, the hybrid seed and Indian hemp, may of us something to say. However it's a fun way to see the world?

5:37

Now, check any ideas — I said that this literary ploy is that it gives us? And when you talk about nature, which is actually my subject as a writer is how she meets the test of Aldo Leopold? Namely, if it makes us better citizens of the society of flora and fauna? Forcing us to do things that support and perpetuate wildlife, instead of destroying it? And I would argue that this idea does it. So let me explain what benefits you get when you look at the world thus, in addition to some fun discoveries about human desires.

6:13

On an intellectual level, look at the world from the point of view of other species helps us to cope with the strange anomaly, namely, and that from the sphere of intellectual history — namely, that we have the Darwinian revolution 150 years ago... Oh, mini-me. (Laughter) we Have this intellectual revolution of Darwin in which, thanks to Darwin, we realized that we are just one species out of many; evolution is working on us the same way as it works on all the others, we act and not only we are acting; we are really in the fiber, in the fabric of life. But the strange thing is that we have not learned this lesson over 150 years; none of us truly believes it. We are still Cartesians — the children of Descartes-who believe that subjectivity and consciousness separates us, that the world is divided into subjects and objects that is the nature on the one hand and culture on the other. As you begin to look at things from the point of view of plants or animals, you realize that this literary ploy is the idea that nature is the opposite culture of what consciousness is most important. And this is another very important lesson.

7:37

Look at the world from the point of view of other species is a cure for the plague of human vanity. Once you understand that consciousness, which we appreciate and believe in the highest achievement of nature, human consciousness — is really just another set of tools to survive in this world. And it is quite natural that we think this is the best tool. But, you know, is a humorist, who said: "And who tells me that consciousness is so good and important? Consciousness itself". And when you look at the plants, you realize that there are other tools that are just as interesting.

8:18

I'll give you two examples, also from the garden: Lima beans. You know that the Lima bean does when it is attacked spider mites? It releases a volatile chemical, which spreads and attracts the mites of other species that come and attack the spider mite, defending the beans. That is, the plants — while we have consciousness, tool-making, language, they have biochemistry. And they have perfected it to such an extent that we cannot imagine. Their complexity and sophistication worthy of admiration, and I think that this is actually the scandal of the human genome project. You know, we started recommending 40,000 or 50,000 human genes, and was only 23,000. To give you a grounds for comparison, rice 35 000 genes. So who's more advanced? We are all equally advanced. We evolved during the same time, just in different ways. Here, the cure of vanity, a way to feel the idea of Darwin. And that's what I do as a writer, like a storyteller, trying to get people to feel what we know and tell stories which help us think ecologically.

9:43

Now, another use of this practice. I will lead you now to the farm, because I used this idea to develop their understanding of the food system, and I found out that all of us are now manipulated corn. The report about ethanol, which you heard earlier today, for me it is the final triumph of corn over common sense. (Laughter) (Applause) That's part of the plan of corn to take over the world. (Laughter) And you will see the amount of corn planted this year will be much higher than in the past, and it will be so much more given space, because we decided that ethanol will be fruitful for us.

10:23

So it helped me understand industrial agriculture, which of course is a Cartesian system. It is based on the idea that we subjugate the other species to our will and that we are important, that we create a factory and includes such technological things, and out for food or fuel or whatever we want. Let me show you a very different type of farm.

10:43

Is a farm in the valley of Sananda in Virginia. I was looking for a farm that would use the idea of looking at things from the point of view of the species, and I found this in man. The name of this farmer Joel Salatin. I spent a week as an apprentice on his farm and collected enough encouraging facts about our relationship with nature, the stronger of which I have not seen in 25 years that I write about nature. And they are this: it's called Politas that means... the Idea that he's got six different species of animals and also some plants grow in a very thoroughly developed a symbiotic manner.

11:18

This is permaculture, if you know a little about it, is that cows, pigs, sheep, turkeys, and -- what else he's got? All six types — and, even bunnies, all provide ecological services to each other, so that the manure from one lunch to another, and they save each other from parasites. This is a very complex and beautiful dance, but I'll get to only one piece and it's relationship between his cows and his chickens-laying hens. I'll show you what happens if you follow this approach. And it is much more than growing food, as you will see. This is another way to think about nature and a way to get away from the concept of zero sum, the Cartesian idea that either nature's winning or we're winning, and that if we get what we want, the nature will decrease.

12:12

Then, one day, cows in the paddock. The only technology that is used here is this cheap electric fence: fairly new, connected to the car battery. Even I could move the fence on 10 acres and install it in 15 minutes. Cows graze one day. They move, right? They all eat up, intensive grazing. He waits three days, and then we bring something called Aitios. Allawos this is a very shaky structure he looks like a wooden schooner, but he lives 350 chickens. He brings it to the site three days later, opens the door, turns them down, and 350 hens come down the stairs, clucking and bubbling as usual and headed directly to the cow patties.

12:59

And what they do is very interesting: they are poking around cow pies looking for fly larvae. He waited three days, because he knows that on the fourth or fifth day, those larvae will hatch and will have a huge problem with flies. But he waits so long to grow them as much as possible, juicier and tastier, since chicken is a favorite protein.

13:25

So the chickens do their little dance and they push the manure to get the larvae, and in the process they distribute on the ground. The second very useful ecosystem. And third, while they're on this site, of course, they poop a lot and their very nitrogenous manure is fertilizing the field. They then move to another area, and just a few weeks, the grass there is a flash of growth. And after four or five weeks he can repeat. He can graze again, he can mow the grass, it may bring other animals, such as sheep, or can procure hay for the winter.

14:10

Now, I want you to look closely at what happened here. It is a very productive system. And I need to tell you that on a few hectares he grows 10 tons of beef, 10 tonnes of pork, 300 000 eggs, 20,000 chickens, 1,000 turkeys, 1,000 rabbits huge amount of food.

14:27

Know asked: "Can organic food feed the world?" Let's see how much food can be produced on several hectares if you do so... again, give each species what it wants, give him realize their desires, their physiological individuality. Apply this on the case.

14:43

And now look at it from the point of view of grass. What happens to grass if you do? When the ruminant animal eats grass, the grass is cut from this length to this length, and it immediately does something very interesting. For those of you who has been gardening, you know that there are so-called the ratio of the mass of roots and shoots, and what plants need to keep the root mass in rough balance with the mass of foliage, to feel good. So when they lose a lot of leaf mass, they swing the roots; they are as it were burned, and the roots die. And animals in the land to work, chewing those roots, decomposing them — earthworms, fungi, bacteria — and the result is new soil. This creates a soil. It is created from the bottom up. This is how arose the Prairie the interaction of bison and herbs.

15:36

And that's what I understood when I realized it, and if you ask Joel Salatin who he is, he will say that he is not a farmer's chickens or sheep or cows — he is a farmer growing grass, because grass is really the basis for this system. If you think about it, this completely contradicts the tragic idea of nature we hold in our head, that we get what we want, the nature will decrease. The more we are, the less nature. Here, all this food comes off this farm, and at the end of the season there is more soil, more fertility and more biodiversity.

16:21

This is a very encouraging lesson. Now there are many farmers engaged in this. This greatly beyond organic agriculture, which is still a Cartesian system, more or less. It says that if you start to consider other views, to consider the ground that with such a promising idea, since there is no technology, except for those fences, which are so cheap that they can instantly appear all over Africa, we can take the required food from the Land and also the Land to heal.

"Who we really are?": the best selection of TED lectures of scientists and philosophers ofthe Ideology of TED Chris Anderson: why be able to speak every needs

17:03

It's a way to revive the world, and why this view is so exciting. When we bones are inspired by Darwin's discoveries, things that we can do using nothing more than these ideas are very encouraging.

17:18

Thank you very much.published

Put LIKES and share with your FRIENDS!

www.youtube.com/channel/UCXd71u0w04qcwk32c8kY2BA/videos

Source: www.ted.com/talks/michael_pollan_gives_a_plant_s_eye_view?language=ru

Natalya spondylitis: a body without a SOUL is not living

Do not deceive yourself, especially on the way to the registry office and in the hospital!