579

Naomi Eisenberger on why we physically painful to be rejected

Fifteen million eleven thousand four hundred twenty four

A biologist and a social psychologist Naomi Eisenberger argues that the experience of social or emotional pain — not fantasy in a vacuum, but an evolutionary mechanism, formed as a result of the need for social enterprises — which ultimately leads to survival. If you carefully listen to how people describe their experience of social exclusion, you'll notice an interesting pattern: we use the word pain to describe psychologically difficult events: for example, "my heart is broken". Actually, in English there are several ways of expressing feelings related to failure, not just those which usually refer to physical pain. However, the use of such words to denote exclusion or isolation is typical for other languages — not only English.

Why do we describe the experience of social exclusion words associated with physical pain? True sense of social isolation is comparable to physical pain, or is it just a figure of speech? In a laboratory study, we assumed that the "pain" of social rejection (social pain) is not just a lexical expression. Through a series of studies my colleagues and I showed that socially painful experiences, such as separation or isolation, stimulate processes in the same neural areas as physical pain. Here I present data on the basis of which we realized that processes physical and social pain overlap, as well as studies that directly test this imposition. I'll show some perhaps unexpected consequences of that match, and tell us what the General neural scheme for us and what it says about social pain.

Does rejection hurt? Although the assertion that rejection "hurts", it may seem far-fetched, from the point of view of evolution makes sense that when suffering physical and social pain overlap. As mammals, humans are born quite immature, unable to provide themselves with food and protection. Therefore, infants to survive, you need to always be with those who care for them. Later involvement in a social group is critical for survival; its members benefit from shared responsibility for the production of food, fight predators, and caring for children. Based on the fact that social exclusion is so harmful to humans, it has been suggested that during our evolutionary history, the social attachment formed according to the principle of the physical pain system, borrowing the pain signal as a stimulus during social separation. Probably the connection was so important for survival that the painful feelings associated with physical injury, was included to provide the same suffering from social isolation — that people sought to avoid isolation and to maintain closeness with others.

Subsequent studies confirmed these initial data. Subjects who admitted that in daily life often feel unwanted, demonstrated more significant neural activity in response to an episode of social exclusion. In some cases, simply viewing images of stimuli trigger neural areas associated with physical pain.Studies on humans and animals showed that physical and social pain occur similar processes. They come in two brain areas: the anterior cingulate cortex and to a lesser extent in the anterior lobe of the brain. They are both involved, when mammals are experiencing physical pain or suffer from isolation.

As for physical pain, the anterior cingulate cortex and the frontal lobe of the brain that mediate emotional, unpleasant, painful element of the experience. It can be divided into two components: a sensor that provides information about where one feels the stimulus of pain, and emotional, which captures the discomfort of the irritant — as it is banal, because it is. After neuro-surgery, during which removes the element of anterior cingulate gyrus to alleviate intractable chronic pain patients reported that they were still unable to determine the location of the stimulus, but they are no longer bothered by pain. Similar symptoms were observed with damage to the anterior lobe. Damage to the somatosensory cortex — the area responsible for localization of pain prevents patients to determine where there is pain, but leaves a sensual suffering. Brain imaging also confirms this separation. Subjects who, under hypnosis, increased painfulness of the stimulus without changing the sensory component showed increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, but not in primary somatosensory cortex, which is responsible for the sensing element of pain.

Interestingly, some of the neural sites associated with pain, also contribute to the specific behavior during the separation, which is manifested in terms of suffering. Infants of many mammalian species make special anguished sounds (for example, human babies cry) when separation from the conscious subject. These sounds have an adaptive purpose (for adults — it is a signal to find the baby), that is, they prevent the long separation. The dorsal and ventral divisions play a critical role in the production of these sound suffering. Damage in these areas in monkeys eliminates the sound of suffering, whereas electrical stimulation in macaques leads to spontaneous painful screams.

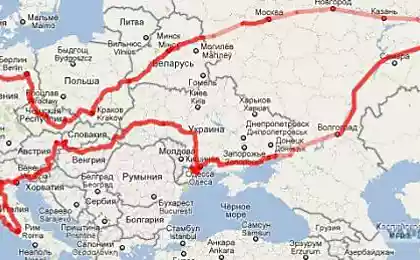

Based on the data, detects neural areas involved in physical pain and suffering of mammals from separation, we decided to investigate whether these sites play a role in socially painful experience. In one such study, each participant was told that on the Internet he will be connected to two others and together they will play the game with passing the ball. The subjects were connected to an MRI scanner. Using special glasses he saw the virtual incarnation of the other two players with their names as well as your arm. By pressing the party to decide who to throw the ball.

In fact there were no other players; participants played with a preset computer program. In the first round, they were included in the game all the time, and the second is excluded because the two other players stopped throwing them the ball. In response to this rejection, subjects showed a strong activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and in the anterior lobe of the brain — two areas associated with physical pain. Moreover, subjects who are more worried about the episode isolation ("I felt rejected," "I feel unwanted") also showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate, confirming the assumption that the failure really "hurts".

Finally, separation or rejection is not the only causative agents of nervous activity associated with pain. Other socially painful experiences, such as bereavement also involves these neural areas.Subsequent studies confirmed these initial data. Subjects who admitted that in daily life often feel unwanted, demonstrated more significant neural activity in response to an episode of social exclusion. In some cases, simply viewing images of stimuli trigger neural areas associated with physical pain. For example, the viewing of paintings by Edward hopper activated the anterior cingulate and the frontal lobe of the brain. In addition, socially sensitive people when watching a video where someone made a disapproving facial expression (possible sign of social rejection), showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate.

Finally, separation or rejection is not the only causative agents of nervous activity associated with pain. Other socially painful experiences, such as bereavement also involves these neural areas. In response to viewing images recently deceased mother or sister (along with pictures of unfamiliar women) participants of the experiment showed increased activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus and frontal lobe. Moreover, women who lost a child the forced abortion, while viewing pictures of smiling infants showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate compared to those who just gave birth to a healthy child. So, various types of socially painful events — from rejection to loss partially rely on those neural areas that play a direct role in bodily pain.

Within the intersection of physical and social pain we can expect interesting results — for example that people are more sensitive to physical pain, and a keener sense of social pain, and Vice versa. This is not a fictional hypothesis, it was tested in several studies. The best proof can be found in the information about patients — people with chronic illness much more than healthy, care about the relationship with your partner, and depressed people with high social sensitivity are more susceptible to pain than those who self-control.

The second result of the intersection of physical and social pain is that the factors of increasing or decreasing one affects the other in the same way. Thus, the factors which are believed to reduce social pain (e.g., feelings of social support) should also reduce physical pain, and those that reduce bodily (for example, pain), also reduces social. We found evidence for both these claims. To find out whether reduces social support to physical pain, we asked women to rate the unpleasantness of the sensations from the hot stimulus applied to their forearm, while they performed various tasks. During one of the tasks they had social support (namely, holding my lover's hand), while others (for example, they held either the hand of a stranger or of a soft ball). We found that participants felt much less pain when held the hand of their partners than when they were with strangers. What is even more interesting, we found that participants felt much less pain when looking at images of their loved ones, than when viewing pictures of strangers or objects. Obviously, even the idea of social support can reduce both physical and social pain.

When I talk about this experiment, people often ask: "If this is indeed true, it means that painkillers can reduce the pain of social suffering?". The question is asked in earnest, because it seems incredible, but actually, the answer is Yes, you can. To test this idea we investigated whether the medicine tylenol to reduce feelings of social pain. The first study, participants took a normal dose of tylenol or a placebo for three weeks. They were asked to assess the daily level of pain. Those who took tylenol, had noted a decrease in pain from 9 until 21, while those who took the placebo did not notice any change. In another study, people take tylenol or a placebo for three weeks and then played a virtual game by passing the ball (which they are in the end subjected to social exclusion). As shown by an MRI scanner, those who took tylenol, in response to the social isolation of neural activity was less. These studies show that, no matter how it was amazing, analgesic tylenol also eliminates social suffering.

Though painful, the torment and emotional pain due to damaged social relations performed the valuable function-namely, maintaining close social ties. Because rejection hurts, people are motivated to avoid situations in which possible rejection.Some other consequences of crossing physical and social pain were also investigated. One phenomenon can be better understood in the light of this crossing — aggression caused by the failure. For years people have puzzled over evidence that marginalized subjects are more likely to act aggressively towards others. This is actually close to the truth — one need only recall the frequent news about the shooting at the school, which hosted the students, who were described as outsiders. In fact, in thinking about that rejection triggers aggression, makes sense; although it would seem, given the importance of maintaining social ties, why in a situation of isolation a person is predisposed to aggression rather than prosocial behavior? Wouldn't it be more logical if it was trying to restore social ties? However, in light of the intersection of physical and social pain aggressive reaction to the insulation is more than justified. From the studies it is well known that animals in response to pain stimulus attack those next. Probably it is this adaptive function: when the threat of physical damage they attack. If the social pain really is part of the system a physical, aggressive response to social rejection may be a by-product of the reaction on the bodily pain is such an inadequate adaptive function in a social context.

Another possible consequence of crossing — physiological stress that occurs in response to social threat situation. It is well known that cases of physical threat induce a physiological response (e.g., increased levels of cortisol) to mobilize energy and resources. However, it was also shown that socially dangerous situation — as, for example, speech to strict or hostile audience can cause the same physiological reactions, also to increase the level of cortisol. While it seems logical to mobilize energy in a physically dangerous situation, it is unclear why it is needed to body in the possibility of negative evaluation or rejection by others. However, if the threat of social rejection is interpreted by the brain in the same way that the threat of physical damage, physiological stress can be triggered in both situations.

One of the conclusions described discoveries: separation or parting can also undermine the body as physical pain. Even if we treat bodily pain seriously and believe it is more reasonable to worry about the pain of social loss can be equally heavy, which proves the activation of the nervous system.

One may wonder, for which people have to carry this heavy burden — social-physical pain? Though painful, the torment and emotional pain due to damaged social relations performed the valuable function-namely, maintaining close social ties. Because rejection hurts, people are motivated to avoid situations in which possible rejection. Over evolutionary history, the maintenance of social ties increased the chances of a person to life and reproduction. The experience of social pain, while temporarily painful, is an evolutionary adaptation that promotes social unity and, therefore, survival.

Source: theoryandpractice.ru

Yuri Lapin: the World is building skyscrapers and houses out of straw

Harm the ethics of vegetarianism