290

The pleasure of the opposite: why we love hot peppers, boxing and zombie movies

© Lonneke van der Palen

Homo sapiens’ advanced intelligence not only creates problems unknown to other animals, but also expands the range of pleasures we receive in an unusual way. Yale psychology professor Paul Bloom, in his book The Science of Pleasure, explains why we are able to enjoy the weirdest things from shopping to cannibalism.

How does security change the impression of fiction? For starters, it helps us to enjoy the pain and death of others. You can laugh over the stage when a pedestrian falls through the manhole because you don't worry about him dying or being crippled, you don't think about the grief of his wife and children because you know the character is fictional.

Increased tolerance for violence is evident in video games. Often, they offer emasculated versions of pleasant real-world experiences - air and car simulators simulate the fun of flying and racing. This can explain much of the violence in video games. Usually in the game you get into a simulation, where the hero does something fascinating, while morally flawless: protects the world from evil aliens, Nazis, zombies, zombie Nazis. Players would love to do something like this, if it were safe.

But there are also darker pleasures. Video game security allows people to pursue their worst intentions. Most players sometimes shoot their team members in the head, crush pedestrians or ram a building with their plane (in the 1982 Microsoft Flight Simulator game, the simplest target was the Twin Towers in New York). Some time ago, while playing The Sims, a computer game where you create your own imaginary world, my children and I deprived a person of food and sleep for several days and watched them scream, ask and cry. When he died, we greeted the event with cheers.

Sometimes worse. In Grand Theft Auto you can kill prostitutes. There are games like Japan’s Rape Lay where the goal is to do evil. You wonder who is playing these games. In any case, the safety of these games (physical, legal, getting rid of worries for others) allows you to realize sadistic motives, which people presumably would not go to in real life.

This idea may help us solve a long-standing puzzle about the pleasure of fiction, which was formulated in 1757 by David Hume: “It seems that viewers of a well-written tragedy get immeasurable pleasure from sadness, horror, anxiety and other passions that are themselves unpleasant and disturbing. The more they are touched and hurt, the more they admire the performance. They are satisfied to the extent that they are grieved, and are never so happy as when they sigh, sob and weep to release their sorrow and relieve a soul overflowing with the strongest sympathy and compassion.

Hume marvels at the fact that viewers of a tragedy enjoy emotions that are usually not very pleasant - sadness, horror or anxiety and so on - but the more they experience them, the happier they become.

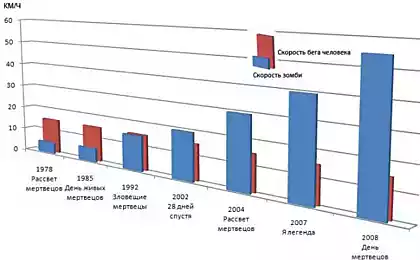

“The scarier the film, the better. As Hume would put it, if he lived these days, negative emotions are not a bug, but a built-in function. This mystery becomes even more acute when we address what philosopher Noel Carroll calls the paradox of horror. Unlike tragedies, horror films rarely have outstanding aesthetic or intellectual qualities. But people like them, and they line up to watch innocent people being killed, tortured and eaten by zombies, psychopaths with axes, sadistic aliens, swamp critters, angry babies and - in the long-running movie Rabid - a phallic sting under the arm of an attractive woman. The past decade has brought us films like Hostel and Saw, in which the depiction of sadistic torture plays a central role. And watch them not only a few perverts: films about torture (in the genre of torture porn) are shown in multiplexes along with serious dramas about how divorced women find love again, and stupid comedies with the participation of sassy donkeys helping the main character.

Keep in mind that the mystery here is not just how we overcome the unpleasant sensations of death and pain. The question is why we like them so much. "Friday the 13th" wouldn't have become a more popular movie had Jason attacked people with a Nerf brand baseball bat, nor would "Hamlet" have become a standout play had the protagonist lived happily ever after. People love horror movies because they are scary. And at least on a crude, primitive level, modern movies are far scarier than movies of the past, and that reflects the dynamics of supply and demand. The scarier the movie, the better. As Hume would put it, if he lived these days, negative emotions are not a bug, but a built-in function.

Unpleasant emotions of this kind are not necessarily attractive because of their low quality. In 2008, the New York Times published a discussion about Blasted, a very popular play whose tickets were sold out long ago and the reviews were rave. The article described a scene where one man rapes another and then sucks his eyes out. The audience of this play is older people, rather sophisticated and successful, and not sloppy teenagers trying to prove to each other who is cooler. But no one interested in this production would say that the play would have become more popular if the themes of rape and cannibalism had been muted a bit. The audience likes this scene, and the play is successful in part because of it.

One explanation was put forward by Aristotle (Freud refined it and made it popular). This is catharsis: certain events initiate a process of psychological cleansing, during which we get rid of fear, anxiety and sadness and then feel better, calmer and cleaner. Thus, we experience repulsive experiences for the sake of positive returns in the end – for the sake of relief.

Maybe that’s true, there are people who say they get better if they cry.

However, the theory of catharsis is not supported by scientific data. That emotions are supposedly cleansed is wrong. Take a well-researched case: watching a violent film does not relax the viewer and does not bring him to a peaceful state, but, on the contrary, excites. People do not leave a horror movie, experiencing good nature and calm, and watching the tragedy does not lead us to a frivolous mood. A person who has experienced unpleasant sensations usually feels worse, not better. The pleasure of horror and tragedy, therefore, cannot be explained by an enthusiastic residual feeling.

Let’s leave the fiction for a moment and consider another mystery: why do young animals, including humans, start game fights? Why do children enjoy pushing and knocking each other down? This is not just a desire to train muscles: in this case, they would rather perform push-ups and squats. This is neither sadism nor masochism. The struggle itself brings joy, not pain or pain.

The answer is this: play is a form of practice. Wrestling is a useful skill, and practice allows you to develop it. If you fight many times, you will fight better. But if you lose, you can die or become crippled, and the winners break their fingers, break their noses and suffer. How do you get what you need without suffering? Here’s an ingenious solution: Animals that are friends or related can use each other to develop their fighting skills while holding themselves back so no one gets hurt. That's what game fights are all about.

“The zombie theme is a clever way to tell a story about strangers being attacked and betrayed by those we love. This is what attracts us, and brain-eating is only a bonus. The more you practice something, the better you do something. But real-world experiences can be costly, so people tend to engage in certain physical, social, and emotional “training” safely. Sport is a physical game, entertainment is intellectual, and stories and dreams are social, in which we indirectly and safely explore new situations.

In many ways, our games take place in our heads, and it helps us to understand our desire for disgusting fiction. Just as a game fight involves putting a participant in a situation dangerous in the real world, our games often lead us with imagination into situations that involve elements that are unpleasant and sometimes terrible — if they actually happened. Stephen King says we make up horrors to help us deal with real horrors. It is a way of helping the practical mind to cope with terrible problems.

We are drawn to the worst of events. The details aren't that important. We don’t like zombie movies because we’re preparing for a zombie uprising. And we don't need to plan anything in case we accidentally kill our father or marry our mother. But even such exotic situations are a useful practice in case of something terrible, psychological training in case the world turns into hell. From this point of view, it is not the zombies themselves that make zombie movies fascinating. Just the zombie theme is a deft way to tell a story about being attacked by strangers and betrayed by those we love. That's what attracts us, and brain-eating is just a bonus.

Some people avoid movie horrors, just as some never get into a game fight. But there are other ways to prepare for the worst, and everyone chooses their own poison. You might not like Chainsaw Massacre 3, but you might be interested in exploring losses in The Language of Tenderness (Mother Dies of Cancer) or The Sweet Hereafter: children, a school bus, a cliff. You can also stop on the road to watch an accident. Plato wrote about this vice. In the Republic he mentions the Athenian Leontius, who saw the corpses of those executed near the city wall. He wants to look at them, but turns away, fights with himself, and eventually runs to the corpses and says to his eyes:

“Behold, you who are ill-fated, be satisfied with this beautiful sight!” Bodies are real, but they can be viewed safely from a distance, and the desire to look at them is similar to what draws us to imaginary blood and imaginary death.

Paul Rosin has pointed out other instances where we deliberately expose ourselves to pain in controlled doses. For example, exclusively human pleasure from spices like hot pepper and drinks like black coffee. This also includes too hot baths, frying yourself in the sauna, fighting nausea and fear on a roller coaster, causing yourself moderate physical pain - pressing your tongue on a sick tooth or placing weight on a sprained ankle.

Can this “harmless masochism” be explained by a desire for safe practice? Perhaps not: Why practice eating spicy foods or taking hot baths? These examples of Rosin may have a utilitarian explanation. Remember the joke about the man who beat his head against the wall. When asked why, he replied, “It’s so nice to stop.” In some examples of Rosin, the initial pain may be justified because it is outweighed by the subsequent pleasure. We can develop the ability to enjoy a hot bath because it is always followed by bliss when the temperature drops to normal levels.

published

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru

Vegan cranberry-cherry crumble without flour

Perfume for workaholic: smells affect performance, memory and concentration