630

Why is the smell so hard to describe in words

Try to describe the wonderful Bordeaux that you drank at dinner last night. If you are Robert Parker, your speech is likely to be brief. That's because smells (which make up the lion's share of what we usually call "taste") is extremely difficult to describe in words. Recently scientists were able to understand something about the nature of this phenomenon. In one of the latest studies report on the "communication gap" between the olfactory center of the brain and the language system. At the same time, linguists working with aboriginal people of South-East Asia, presented a new result: they questioned the fairness of the generally accepted view according to which all people describe smells equally bad.

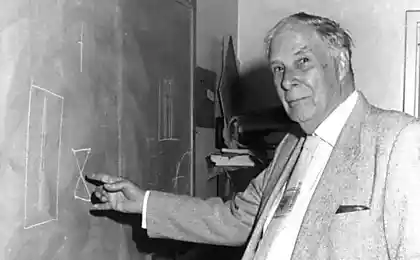

Psychologists say that ordinary people without special training are able to recognize known odors like coffee or sunflower oil, about half of the cases. "If someone showed the same modest results in the test for visual definition of familiar objects, he would be sent to a neurologist, says Jay Gottfried, a neuroscientist at northwestern University, Illinois. — People as if there is neurological defect in identifying smells."

Whatever the problem was, she's probably not in the ability of our olfactory system. Humans have about 400 different types of receptors for the perception of aromatic molecules. The number is quite small for mammals, but it's enough — at least theoretically — to distinguish a trillion different smells.

When people — at least English-speaking — describe smell, they are primarily referred to as its source: orange-like, smoke-NY, etc. This is quite natural, but other sensory experiences we described a fundamentally different way. Words like "white" and "round" referred to the visual properties of the object but not the object itself: these properties could have a Golf ball and the moon. Similarly, the sound can be "piercing", regardless of, makes it a bird or a boiling kettle.

Best describe my olfactory experience those who do this for a living: wine critics, perfume makers, and etc. However, experts also commonly referred to using similar fragrances smell things (perhaps this is yesterday's Bordeaux gave graphite, black currants and camphor). Their descriptions are not always clear to mere mortals like us, especially when it begins to use abstract vocabulary.

In the North-West University doctor Gottfried studied the people on the other end of the spectrum — patients with so-called primary progressive aphasia, which is the worst of all possible to describe smells. Unlike patients with Alzheimer's, their problem to a greater extent with it than with memory.

Patients with aphasia are particularly bad at it to identify the normal smell, like the smell of roses, onions or petrol: they answer correctly only 23 % of cases (control group answers correctly in 58% of cases, as reported by Gottfried and colleagues in an article published in the journal Brain last year). However, when the researchers suggested that those patients with aphasia choose the name of the odor from a list, they handled almost as well as a control group. It caused Gottfried to assume that a) their sense of smell is not affected, b) despite the aphasia, they know the right words. Rather, the relationship between the olfactory center and parts of the brain responsible for speech, said the scientist.

The study also was attended by component of brain-imaging: based on data from the scanning MRI machine, the researchers found that people experiencing the greatest problems with the naming of odors, had damage in the frontal lobe of the brain.

A recent study of Gottfried, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, also points to this area of the brain as key in the process of information transmission between the centers of smell and speech. This time, Gottfried and his colleagues asked healthy volunteers to identify common odors; at this time the sensors are EEG and functional MRI recorded their brain activity. It was found that, on average, two areas of the brain are activated when determining the odors: the front part of the temporal cortex (the same area that were involved in the earlier experiment involving patients with aphasia) and the orbitofrontal cortex — the area located immediately behind the eyes, which is often associated with decision making (but, like many other parts of the brain she supposedly has other functions, and most of them we know almost nothing).

As noted by Gottfried, both of these areas receive a direct signal from the pear-shaped lobe of the cerebral cortex is the main "relay station for olfactory signals. Perhaps this is a direct link between sense of smell and it is the reason that we struggle to describe odors. The information coming from the olfactory system in the language center of the brain can be compared to a couple of lines, nakoryabano on a napkin: she processed much less than the information that is sent from the centres of sight and hearing, which is more similar to the edited draft, because it goes through several additional stages of processing in specialized sensory areas of the brain.

This neurological failure of communication may not be universal, says Asifa Majid, a psycholinguist at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands. Majid worked with two populations in Southeast Asia, languages which describe the smells not like English.

Manik — the language spoken by a small group of nomadic hunters and gatherers in southern Thailand. The smell is one of the most important components of all aspects of their lives, from food production to the use of medicinal herbs and ritual. "For example, teledu, or hog badger (Arctonyx collaris) is described as "smelling" [caŋə] (a pleasant smell that is often associated with different food) — in the dry season, says Majid and her colleague Evelyn's Grandson in a study published this year in the journal Cognition.

— However, during the rainy season, badger produces an unpleasant smell, resembling the smell of Varan". In the language of Manik, unlike English, is very rich descriptions of the scent through abstract properties, rather than through their source, Majid and celebrate Grandson.

The same is true for jahai language, which is spoken on the Malay Peninsula, Majid writes in another article Cognition. Together with Niklas Burenhult she had a test, which involved 10 media jahai and 10 native speakers of American English to compare their ability to describe common odors. The same participants were asked to name and a series of colors. English-speaking subjects were very consistent in their marking colors: different people used the same words, but in the description of odors reigned complete mess. Media jahai, on the contrary, more often agree with each other in naming the odors. In fact, the odors they called so smoothly, as the colors, although the colors described less consistently than native speakers of English.

As those who speak the language of Manik, media jahai used in the description of the smells of abstract categories that reflect the importance of smell in their lives. Goiskoe word [cŋəs], for example, very roughly can be translated as "to smell like something edible" (so, the smell of cooked food or sweets), and [plʔɛŋmeans] means "the smell of blood that attracts tigers" (as crushed lice or squirrel blood).

According to Gottfried, open Majeed suggests that the use in some languages of abstract characteristics that encompass a lot of smells at once, allows people to circumvent a neurological "defect" in the definition smells. In other words, it is possible that to define an abstract term that describes the smell, it is easier than to pinpoint a direct source of flavor.

Myself Majid prefers another interpretation. It suggests that in some cultures, people deal with a defect of description of odors by changing their own brain: "To the native speakers jahai was able to talk about smells the way they do, areas of the brain that process language data must have access to olfactory information," she writes. — We can assume that mastering the "language of smell" that people "learn" in children, is a major component of this process."published

Source: mtrpl.ru/smells-and-words

The mystery of the shroud of Turin - or what we don't know about the Resurrection of Christ

Baked mackerel