295

When the Face Fakes: Harold Zakheim's "Left" Experiment

“Lie Me” or “Theory of Lies”

Once to the American psychologist, Professor of the University of California San Francisco, the largest specialist in the field of lie recognition Paul Ekman (Paul Ekman), addressed his colleague, Harold Sackeim (Harold Sackeim), Professor of clinical psychology and psychiatry at Columbia University.

Harold Zakaim (and his colleagues) set out to conduct an interesting experiment, for which he needed photographs of faces expressing different emotions.

And Ekman, for many years studying facial expressions, collected a huge archive of such photos. So Zakaim asked Ekman to lend him emotional illustrations for the experiment.

- Sure, dear colleague! Ekman probably replied and lent Harold Zakaim the illustrations.

If you’re not familiar with Paul Ekman’s work, the easiest way to do so is by watching Lie to Me.

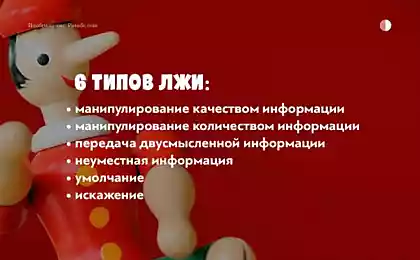

Lie theory

In the series, of course, it's not Paul Ekman, but "Dr. Lightman" (played by Tim Roth).

But, in fact, watching the work of Dr. Lightman, you will learn the scope of many years of scientific research by Paul Ekman.

Lie theory is the easiest and most accessible way to get acquainted with the works of a great scientist. Professor Ekman is a consultant to the series.

But back to Harold Zakaim. After receiving the photos, Zakaim and his colleagues reproduced these photos and cut them.

Sliced Brad Pitt

Did you cut it? you ask. Why?

That's why.

The Zakaim experiment Suppose Zakaim took a picture of Brad Pitt and cut it. He cut it so that only the right half of the face was on one part, and the left on the second.

After that, Zakaim folded the face of Brad Pitt again, but only from one left or one right halves.

From the left: from the right halves: from the left halves

The result was two Pitt mutants. It may seem strange to you, such a terrible transformation with a Hollywood sex symbol: but consider that we are on Pitt training, and Zakaim used photos of unknown people.

What kind of faces do people have? Anything.

After taking photos of mutants, Zakaim presented them to different people and asked them to answer: which person, in their opinion, is more emotional?

You can try it yourself: look closely at the photos of the Pitt mutant and tell me which one is more emotional. Right or left?

Respondents’ answers consistently coincided: a face made up of left halves is more emotional.

Anger. Fear. Sadness. The left face was invariably more emotional than the right face.

In one case, respondents found no difference between left and right.

They were people with happy expressions.

In all other cases, the left half of the person’s face was invariably more emotional than the right.

The result of the experiment was expected for Zakaim. Expected because that was his assumption, his hypothesis. The left side of the face is more emotional. But why?

Here's why.

There is such a thing as “brain asymmetry”. Or hemispheric asymmetry. In simple terms, the right hemisphere of the brain is responsible for the left part of the body, and the left – for the right. So is asymmetry.

Which hemisphere controls the left hand? Right.

Which hemisphere controls the right hand? Left.

Which hemisphere controls the muscles of the right side of the face? Left.

Which hemisphere controls the muscles of the left side of the face? Right.

And so on.

Each hemisphere has its own specialization.

The left hemisphere is responsible for writing and billing. When you analyze something, the left hemisphere does it.

The right hemisphere imagines, dreams and fantasizes. If you want to imagine what Hitler looks like, painted in a zebra, the right hemisphere will help you.

It is known that the right hemisphere is responsible for the emotional sphere of a person.

And therefore, Zakaim suggested, the “left face” (which is controlled by the right hemisphere) would be more emotional, more mimically expressive than the “right face.”

This was fully confirmed in his experiment.

Well, almost completely. Except for the lucky ones mentioned above.

Zakaim did not draw any conclusions from this, and published the results of his experiment in the journal Science (1978).

But when Ekman read his colleague's article, his eyes were swelling on his forehead.

And there was a reason to climb.

Happiness symmetry And the thing is, Ekman's photographs provided to Zakaim were -- um -- not exactly homogeneous.

Most of the photos were staged. Ekman asked people to move their facial muscles to get the emotion they needed.

Only the pictures of the happy faces were genuine. Ekman did them without warning, in a moment when people were really having fun.

At the time Zakaim asked to lend him the illustrations, Ekman did not attach any importance to it. Some are staged, some are genuine. Who cares?

When a person smiles, a certain group of muscles moves. When she's angry, another. When upset, third. If you move these muscles intentionally, the result on the face will be the same as in the case of genuine emotions.

But when Ekman read Zakaim's publication, he found there was a difference. And that the people who were the exception in his illustrations, for some reason, defy Zakaim's rule of emotional facial asymmetry.

The conclusion is obvious: asymmetry occurs when a person shows a false emotion. Artificial emotion. An intentional emotion.

If the emotion is real, then facial asymmetry is practically absent.

Ekman tested and double-checked this conclusion, and the result was the same: when people “fake” the face, the emotion appears on the face asymmetrically. The left face is more emotional than the right. If Zakaim had known he was working with "fake" emotions, perhaps he would have come to a similar conclusion.

Conclusion

Paul Ekman was initially skeptical of his discovery. “Asymmetry is so subtle that it is almost impossible to determine it without accurate measurements,” he writes in his book, The Psychology of Lies.

The professor is understandable. After all, when he conveyed “fake” emotions to Zakaim, he had no idea that they were any different from genuine emotions.

If he, a psychology professor, had looked at the fact that a strained, fake, “made” emotion was unevenly distributed across the face, would anyone else notice?

However, this skepticism broke at the first check.

Left: actor Dolph Lungren Right: actor George Clooney

When asked whether a person's expression is symmetrical or asymmetrical, the percentage of correct answers was significantly higher than the random.

Through various experiments, Paul Ekman made many refinements to his initial conclusion.

For example, a left-handed smile is slightly less asymmetrical than a right-handed smile.

In some cases, emotional facial asymmetry manifests itself on the left, and in others - on the right side of the face. Anger and smile are more pronounced on the left face. Fear and disgust on the "right."

Ekman also found that in "made" emotions, not only the face, but also certain movements can be asymmetrical.

I repeat that in all these cases we are talking about fake, staged, simulated emotions.

Regarding genuine emotions, the conclusion remained unchanged:

If the emotion is real, then facial asymmetry is almost absent.

Watch your acquaintances. For colleagues at work. Politicians on TV. This is a very interesting and very productive way to understand the sincerity of the emotions that people around you broadcast. published

Author: Wit Zeneve

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: psyberia.ru/psyhodiary/ekman