271

The Burden of Knowledge: How Doubt Helps Us Develop

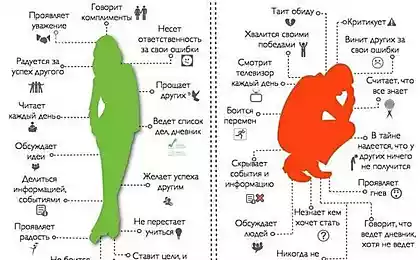

Knowledge increases our self-esteem and self-confidence, but makes us dependent on the opinions of authorities and deprives us of the opportunity to look at the problem from a new angle.

Also, knowledge is easy to simulate!

We publish excerpts from Knowledge Is Not Powerful about the dangers of education and how ignorance can enlighten. The authors of the book are international education and career consultants Stephen D’Souza and Diana Renner.

Knowledge is power.

The baby, stumbling, takes the first steps, and her parents shine with happiness, pick her up in their arms, caress. The girl utters the first words, sings a song in the kindergarten, receives a prize for literacy in the first class - and everyone praises her, everyone rejoices.

From the first days of life, we are praised, valued and rewarded for each knowledge we have acquired, for new skills. Francis Bacon's famous aphorism "Knowledge is power" It has become a cliché that is embarrassing to repeat. School, work, life experience – everything convinces us that our status depends on competence, and it must be demonstrated, made visible to others. This determines the degree of influence, power, reputation of a person. It is the external manifestation of knowledge that attracts attention, gives a person value.

In recent decades, both developed and developing economies have continued to shift inexorably from manufacturing to services. More and more people are choosing jobs where “we’re paid to think.” In many countries, the availability of a diploma promises an increase in income, since it opens up access to higher positions. Higher education is also correlated with better health, longer life expectancy and fewer children in the family. And the power, the status that we gain through knowledge and competence, gives us a sense of importance and importance. Our self-confidence grows, ambition is kindled: we strive for success, for an even higher status.

The writer and philosopher Nassim Taleb reminds us that we tend to view knowledge as “personal property to be protected and protected.” This is an honorable distinction, it helps to climb the hierarchy. A frivolous attitude is inappropriate here.”

The thirst for knowledge is strongly encouraged in us by social institutions that reward us for acquired skills and competence. Our activities are evaluated according to certain criteria that provide promotion, earnings, bonuses and other awards. Thus, the conviction that success, career and salary depend on competence is nurtured and strengthened.

But it's not just about differences and rewards -- the satisfaction of knowledge, of the sense of certainty that we experience, is not just from the outside, it's an innate property of the brain.

Recently, neuroscientists conducted a study that showed: certainty is one of the main conditions of normal existence. Neuroscientist David Rock believes the threat of uncertainty is as painful as a physical attack. His opinion is supported by another study, according to which even a slight uncertainty the brain begins to react as a mistake. It is impossible to live in a state of uncertainty in matters that are important to us: not knowing what our boss wants us to do, or waiting for the results of tests in fear of a possible diagnosis. Our brain is always in a hurry to get answers.

Neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga from the University of California studied this brain function on the example of epilepsy patients who underwent surgery to dissect neural jumpers between the hemispheres of the brain. The experiment was conducted with each hemisphere separately, and Gazzaniga discovered a network of neurons in the left hemisphere, which he called the “interpreter”. The left hemisphere is constantly busy interpreting information, it “always finds reason and order, even where there are none.” It is no wonder that we are greedy for knowledge in all forms, because it is so tempting! Knowledge promises us respect, awards, promotion, they promise wealth, health, self-confidence.

Nevertheless, caution will not hurt here. When was the last time you were offered the perfect product with many advantages and no disadvantages? The problem of knowledge lies in its absolute benefit. We cling to learned knowledge, even when it binds us, preventing us, paradoxically, from learning new things and moving forward.

Commitment to the known

Padua, 1537 Andreas Vesalius, a young anatomist from Flanders, enters the city gate and heads for the university. With him - scanty possessions, in his chest - a fiery thirst for knowledge, the young man dreams of understanding how the human body works. He came to the right place at the right time. During the Renaissance, located 35 km from Venice, Padua quickly became the international capital of the arts and sciences. Vesalius entered the most famous European school of medicine and anatomy: by then the University of Padua was more than 200 years old.

Vesalius was born in Brussels in 1514 in the family of a court apothecary. Since childhood, he was fascinated by the secret of a living organism. He caught dogs, cats and mice and dissected them, and later stole a corpse from the gallows to get a skeleton, an audacity for which he and his family could pay dearly.

At the age of 18, the thirst for knowledge attracted the young man to Paris, where he enrolled in a medical course. There he got into the hands of the work of the founder of anatomy as a science - the Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher Galen of Pergamon.

Andreas Vesalius

Galen for centuries remained the largest value in the world of medicine. His writings reflect his extensive experience treating patients, from wounded gladiators to three Roman emperors. Galen tried to explain not only the structure of the human body, but also how it functions. For example, he showed how voice sounds arise in the larynx, the first to reveal the difference between dark venous and bright arterial blood.

For centuries, physicians firmly believed every word of Galen. Even in the Renaissance, almost a millennium and a half after Galen's death, his description of the human body remained the main reference for physicians and anatomists, the basis of the doctor's knowledge.

And Vesalius, like all medical students, was at first fascinated by Galen's discoveries: they seemed so clear and convincing. But as he immersed himself in anatomical research and rereaded Galen’s text with an increasingly critical eye, the young man began to discover inconsistencies and minor errors. His doubts about the truth of some of Galen's claims were heightened by attending public and private university lectures.

Galen book cover

At that time, the anatomical session was a notable event: students were stuffed into the audience, visiting scientists were invited. The event was held under strict supervision, as if a sacred ritual, deviations from tradition and strict university rules were considered unthinkable.

The professor of anatomy sat away from the surgeon's desk on an elevated elevation, in a huge chair. His duty was to read aloud pieces of Galen’s books while the surgeon performed an autopsy and a specially appointed person showed the audience the organs and parts of the body that were to be examined.

Although these sessions were directed by well-known scientists, Vesalius came to the conclusion that new knowledge is not acquired, the only purpose is to confirm Galen’s long-held conclusions. The blind devotion to Galen went so far that the surgeon, holding the human heart in his hands and seeing it with his own eyes, commented, as Galen taught: the heart is three-chambered.

A few years later, Vesalius wrote that any attempt to argue with Galen seemed inadmissible, "as if I allowed myself to secretly doubt the immortality of the soul." Galen's book reflected a steady state of knowledge, certainty, comfort zone.

And even though we wouldn't rely on ancient Roman anatomy today, We are still subject to the same error: we fully trust the reliability of the knowledge already obtained..

Artist: Between Angels and Demons

Artists feel at home on the edge of the unknown. Creativity is just in that space. This space opens up after an event commonly described as ego destruction.

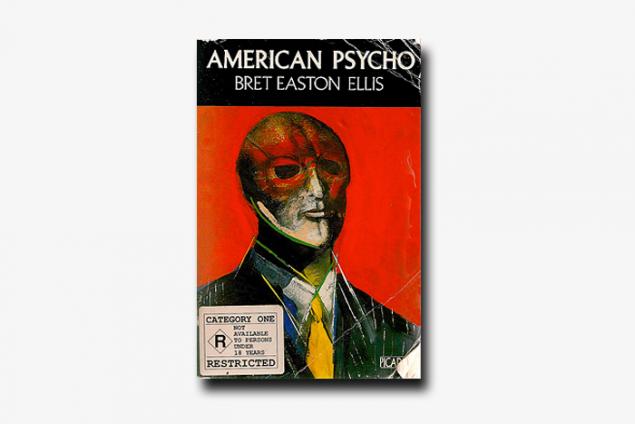

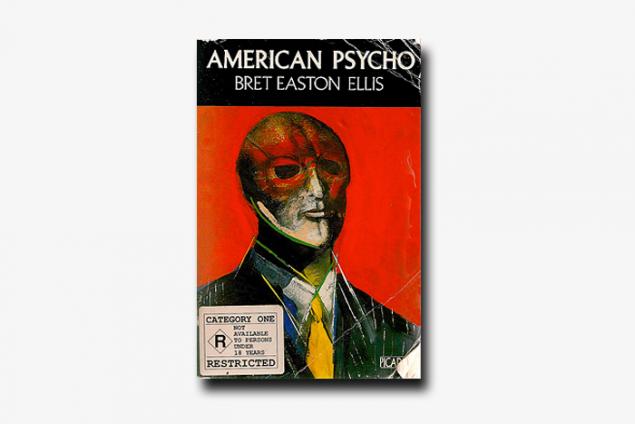

American artist Marshall Arisman (born 1937), illustrator, storyteller and educator, has frequently collaborated with magazines ranging from TIME to Mother Jones. His work can be seen in various collections of the Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of American Art. One of his most famous works is the cover of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho: the main character – Patrick Bateman – appears on it as a half-human half-devils.

Marshall for half a century followed a constant ritual of the creative process. When he woke up in the morning, he dressed and went to the workshop. “My ego leads me there. I stand in front of a white canvas and think, “I’m going to paint the best picture of my life.” But the ego can't draw, it just takes me to the studio! Once in front of an empty canvas, it does not know what to do, and then I begin to paint.

The process of creating a picture always begins with a hint, most often with a photograph. Marshall puts it in front of his eyes and says to himself, "I'll draw this frog." If a frog turns into a pig in the process, it does not prevent it. He never knows in advance where he will come from. Moreover, according to Marshall, the best pictures come out when he does not control the process.

Marshall Arisman.

“Twenty minutes later I notice that I paint rather badly. I argue with myself: “It’s bad, you have to stop, you have to give up, you don’t know how to draw.” This internal strife lasts sometimes twenty minutes, sometimes two hours, until Marshall admits, “It’s still terrible.” And by that point, Marshall explains, his ego is starting to pull back. “Somewhere in this destructive process comes the part of me that can paint. It comes to the fore only when I realize that everything the ego does is useless. There is a small gap, it does not last long, fifteen minutes, but it is enough. I can only get into it by destroying my ego.?

What Marshall ultimately creates comes not from him, but through him. When they say, ‘I like your paintings,’ I say, ‘There’s nothing in them that is mine.’

Mark Rothko also called himself a guide. There was energy going through it. I appreciate this moment of emptiness above all else. I depend on him like a junkie. I’m 75 years old, and now my ego doesn’t want to paint, it just wants to rediscover that space. But it never lasts long.”

Getting rid of the egoIt is a key element of the program that Marshall teaches at the New York School of Visual Arts. The first thing he does is ask students to face the audience and tell a true story about themselves, accompanied by illustrations.

At first, everyone is shy, can not find a natural tone, it is awkward to stand like this in front of friends. But Marshall forces them to repeat their story over and over again, eventually wearing a dog mask.

As a result, students get rid of their ego and, repeating their story, relive its events anew. "They get to the point," says Marshall, whose grandmother was a well-known spiritist. Mediums visited her, I spent my childhood among them. She said, You must learn to live between angels and demons. Angels are fun and seductive, demons are interesting and dangerous.

And now in my workshop, I work in this middle space -- literally. I have angels on one wall and demons on the other. I think Ignorance is the place in the middle, the place of man.published

Also interesting: How to make the mind sharper and more flexible: brain exercises

Don’t do this so as not to hurt yourself.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru/posts/13392-not-knowing

Also, knowledge is easy to simulate!

We publish excerpts from Knowledge Is Not Powerful about the dangers of education and how ignorance can enlighten. The authors of the book are international education and career consultants Stephen D’Souza and Diana Renner.

Knowledge is power.

The baby, stumbling, takes the first steps, and her parents shine with happiness, pick her up in their arms, caress. The girl utters the first words, sings a song in the kindergarten, receives a prize for literacy in the first class - and everyone praises her, everyone rejoices.

From the first days of life, we are praised, valued and rewarded for each knowledge we have acquired, for new skills. Francis Bacon's famous aphorism "Knowledge is power" It has become a cliché that is embarrassing to repeat. School, work, life experience – everything convinces us that our status depends on competence, and it must be demonstrated, made visible to others. This determines the degree of influence, power, reputation of a person. It is the external manifestation of knowledge that attracts attention, gives a person value.

In recent decades, both developed and developing economies have continued to shift inexorably from manufacturing to services. More and more people are choosing jobs where “we’re paid to think.” In many countries, the availability of a diploma promises an increase in income, since it opens up access to higher positions. Higher education is also correlated with better health, longer life expectancy and fewer children in the family. And the power, the status that we gain through knowledge and competence, gives us a sense of importance and importance. Our self-confidence grows, ambition is kindled: we strive for success, for an even higher status.

The writer and philosopher Nassim Taleb reminds us that we tend to view knowledge as “personal property to be protected and protected.” This is an honorable distinction, it helps to climb the hierarchy. A frivolous attitude is inappropriate here.”

The thirst for knowledge is strongly encouraged in us by social institutions that reward us for acquired skills and competence. Our activities are evaluated according to certain criteria that provide promotion, earnings, bonuses and other awards. Thus, the conviction that success, career and salary depend on competence is nurtured and strengthened.

But it's not just about differences and rewards -- the satisfaction of knowledge, of the sense of certainty that we experience, is not just from the outside, it's an innate property of the brain.

Recently, neuroscientists conducted a study that showed: certainty is one of the main conditions of normal existence. Neuroscientist David Rock believes the threat of uncertainty is as painful as a physical attack. His opinion is supported by another study, according to which even a slight uncertainty the brain begins to react as a mistake. It is impossible to live in a state of uncertainty in matters that are important to us: not knowing what our boss wants us to do, or waiting for the results of tests in fear of a possible diagnosis. Our brain is always in a hurry to get answers.

Neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga from the University of California studied this brain function on the example of epilepsy patients who underwent surgery to dissect neural jumpers between the hemispheres of the brain. The experiment was conducted with each hemisphere separately, and Gazzaniga discovered a network of neurons in the left hemisphere, which he called the “interpreter”. The left hemisphere is constantly busy interpreting information, it “always finds reason and order, even where there are none.” It is no wonder that we are greedy for knowledge in all forms, because it is so tempting! Knowledge promises us respect, awards, promotion, they promise wealth, health, self-confidence.

Nevertheless, caution will not hurt here. When was the last time you were offered the perfect product with many advantages and no disadvantages? The problem of knowledge lies in its absolute benefit. We cling to learned knowledge, even when it binds us, preventing us, paradoxically, from learning new things and moving forward.

Commitment to the known

Padua, 1537 Andreas Vesalius, a young anatomist from Flanders, enters the city gate and heads for the university. With him - scanty possessions, in his chest - a fiery thirst for knowledge, the young man dreams of understanding how the human body works. He came to the right place at the right time. During the Renaissance, located 35 km from Venice, Padua quickly became the international capital of the arts and sciences. Vesalius entered the most famous European school of medicine and anatomy: by then the University of Padua was more than 200 years old.

Vesalius was born in Brussels in 1514 in the family of a court apothecary. Since childhood, he was fascinated by the secret of a living organism. He caught dogs, cats and mice and dissected them, and later stole a corpse from the gallows to get a skeleton, an audacity for which he and his family could pay dearly.

At the age of 18, the thirst for knowledge attracted the young man to Paris, where he enrolled in a medical course. There he got into the hands of the work of the founder of anatomy as a science - the Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher Galen of Pergamon.

Andreas Vesalius

Galen for centuries remained the largest value in the world of medicine. His writings reflect his extensive experience treating patients, from wounded gladiators to three Roman emperors. Galen tried to explain not only the structure of the human body, but also how it functions. For example, he showed how voice sounds arise in the larynx, the first to reveal the difference between dark venous and bright arterial blood.

For centuries, physicians firmly believed every word of Galen. Even in the Renaissance, almost a millennium and a half after Galen's death, his description of the human body remained the main reference for physicians and anatomists, the basis of the doctor's knowledge.

And Vesalius, like all medical students, was at first fascinated by Galen's discoveries: they seemed so clear and convincing. But as he immersed himself in anatomical research and rereaded Galen’s text with an increasingly critical eye, the young man began to discover inconsistencies and minor errors. His doubts about the truth of some of Galen's claims were heightened by attending public and private university lectures.

Galen book cover

At that time, the anatomical session was a notable event: students were stuffed into the audience, visiting scientists were invited. The event was held under strict supervision, as if a sacred ritual, deviations from tradition and strict university rules were considered unthinkable.

The professor of anatomy sat away from the surgeon's desk on an elevated elevation, in a huge chair. His duty was to read aloud pieces of Galen’s books while the surgeon performed an autopsy and a specially appointed person showed the audience the organs and parts of the body that were to be examined.

Although these sessions were directed by well-known scientists, Vesalius came to the conclusion that new knowledge is not acquired, the only purpose is to confirm Galen’s long-held conclusions. The blind devotion to Galen went so far that the surgeon, holding the human heart in his hands and seeing it with his own eyes, commented, as Galen taught: the heart is three-chambered.

A few years later, Vesalius wrote that any attempt to argue with Galen seemed inadmissible, "as if I allowed myself to secretly doubt the immortality of the soul." Galen's book reflected a steady state of knowledge, certainty, comfort zone.

And even though we wouldn't rely on ancient Roman anatomy today, We are still subject to the same error: we fully trust the reliability of the knowledge already obtained..

Artist: Between Angels and Demons

Artists feel at home on the edge of the unknown. Creativity is just in that space. This space opens up after an event commonly described as ego destruction.

American artist Marshall Arisman (born 1937), illustrator, storyteller and educator, has frequently collaborated with magazines ranging from TIME to Mother Jones. His work can be seen in various collections of the Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of American Art. One of his most famous works is the cover of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho: the main character – Patrick Bateman – appears on it as a half-human half-devils.

Marshall for half a century followed a constant ritual of the creative process. When he woke up in the morning, he dressed and went to the workshop. “My ego leads me there. I stand in front of a white canvas and think, “I’m going to paint the best picture of my life.” But the ego can't draw, it just takes me to the studio! Once in front of an empty canvas, it does not know what to do, and then I begin to paint.

The process of creating a picture always begins with a hint, most often with a photograph. Marshall puts it in front of his eyes and says to himself, "I'll draw this frog." If a frog turns into a pig in the process, it does not prevent it. He never knows in advance where he will come from. Moreover, according to Marshall, the best pictures come out when he does not control the process.

Marshall Arisman.

“Twenty minutes later I notice that I paint rather badly. I argue with myself: “It’s bad, you have to stop, you have to give up, you don’t know how to draw.” This internal strife lasts sometimes twenty minutes, sometimes two hours, until Marshall admits, “It’s still terrible.” And by that point, Marshall explains, his ego is starting to pull back. “Somewhere in this destructive process comes the part of me that can paint. It comes to the fore only when I realize that everything the ego does is useless. There is a small gap, it does not last long, fifteen minutes, but it is enough. I can only get into it by destroying my ego.?

What Marshall ultimately creates comes not from him, but through him. When they say, ‘I like your paintings,’ I say, ‘There’s nothing in them that is mine.’

Mark Rothko also called himself a guide. There was energy going through it. I appreciate this moment of emptiness above all else. I depend on him like a junkie. I’m 75 years old, and now my ego doesn’t want to paint, it just wants to rediscover that space. But it never lasts long.”

Getting rid of the egoIt is a key element of the program that Marshall teaches at the New York School of Visual Arts. The first thing he does is ask students to face the audience and tell a true story about themselves, accompanied by illustrations.

At first, everyone is shy, can not find a natural tone, it is awkward to stand like this in front of friends. But Marshall forces them to repeat their story over and over again, eventually wearing a dog mask.

As a result, students get rid of their ego and, repeating their story, relive its events anew. "They get to the point," says Marshall, whose grandmother was a well-known spiritist. Mediums visited her, I spent my childhood among them. She said, You must learn to live between angels and demons. Angels are fun and seductive, demons are interesting and dangerous.

And now in my workshop, I work in this middle space -- literally. I have angels on one wall and demons on the other. I think Ignorance is the place in the middle, the place of man.published

Also interesting: How to make the mind sharper and more flexible: brain exercises

Don’t do this so as not to hurt yourself.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru/posts/13392-not-knowing