213

10 ways to look confident even when you have no idea what to do next

Self-confidence is the key to success in any situation

How often do we find ourselves in situations where we have to make decisions, guide others, or demonstrate competence, but there’s total uncertainty inside? The art of looking confident in the moment of uncertainty is not just a useful skill, but a real super tool of modern man. This article reveals practical techniques that will help you radiate confidence even when you are in complete confusion.

According to a study by Harvard University psychologists, people who seem confident are 63 percent more likely to get a promotion and 41 percent more likely to choose to lead projects — even if they have the same skills as their less confident counterparts. Impressive, isn't it?

Why is it important to look confident?

Confidence is a social currency. It affects how others perceive us, what opportunities open up to us, and how effectively we can lead others. It’s important to understand that showing confidence doesn’t equal deception or pretense – it’s more of a tool to help you and others overcome a moment of uncertainty before clarity emerges.

According to the theory of the halo effect, people tend to attribute other positive qualities to confident individuals: competence, reliability, leadership abilities. This creates a positive spiral of perception that works in your favor.

10 proven ways to radiate confidence

1st

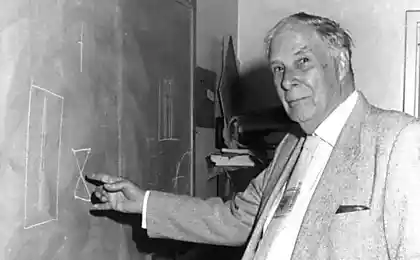

Master the winner's body language

Your body speaks before you speak the first word. Posture, hand position, eye contact are all powerful signals of confidence. Studies show that taking so-called “power postures” before important meetings not only makes you look more confident, but actually increases testosterone (the dominant hormone) and lowers cortisol (the stress hormone).

Practical trick: Before an important meeting or performance, find a secluded place and spend two minutes in the "Superman Pose" - arms on your hips, legs on your shoulder width, chest forward. The effect of this simple technique can last up to several hours.

2.

Learn to speak more slowly

Hasty speech is a sign of nervousness. People who speak slowly and take conscious pauses are perceived as more authoritative and confident. An additional bonus: a measured speech gives you time to think about the next thought.

Practical trick: Practice taking three-second pauses after important statements. These pauses will not only emphasize the importance of what was said, but also create an image of a person who is in no hurry and is in full control of the situation.

3

Learn the Art of Strategic Silence

The ability to remain silent is an underappreciated element of confident behavior. Admitting that you don’t know the answer but know how to find it is a manifestation of strength, not weakness. Answer only those questions in which you are competent, and in other cases use the technique of redirecting attention.

“I don’t know the answer to that right now, but I know how to get it. Let’s get back to that after I do a little research.”

4.

Master the “pre-frame” technique

Framing is a way of setting context for subsequent information. By pre-structuring a conversation or presentation, you demonstrate control over the situation and manage audience expectations.

Practical trick: Start the meeting with the phrase, “Today I want to discuss three key aspects of the project: [aspect 1], [aspect 2] and [aspect 3].” Even if you’re not completely sure of all the details, a structured approach gives the impression of thorough preparation.

5

Use the Power of Prepared Spontaneity

Paradoxically, the most natural and spontaneous performances are often the most carefully prepared. Have a set of universal phrases, stories and examples that can be flexibly adapted to different situations.

Research shows that about 70% of successful executives have a “story bank” – a set of prepared personal and professional anecdotes that they can appropriately use in a variety of situations, giving the impression of laid-back competence.

Think in advance about the answers to the most difficult questions that may arise in your professional field. Practice formulations that sound convincing and leave you room to maneuver.

6

Learn the Art of Reflecting Questions

When you’re faced with a difficult question that you don’t have a ready-made answer to, the reflection technique can give you the time you need to think, while maintaining your expert position.

Practical trick: “That is a very interesting question. Before I answer, I am curious to know what your opinion is on this? or, “In the context of your situation, what do you think is the most important aspect of this problem?”

7

Practice “empathic leadership”

When you don’t know what to do next, focus on understanding the needs and concerns of others. By asking deep, thoughtful questions and listening attentively, you not only get time to think about your own position, but also create an image of a thoughtful leader.

“Leadership is not just about having all the answers, it’s about asking the right questions.”

8.

Use the principle of "pivot point"

In moments of uncertainty, build on your core values, principles, and proven methodologies. They serve as a reliable support when the specific details of the situation are unclear.

Practical trick: Formulate for yourself 3-5 fundamental principles of your professional activity. In moments of uncertainty, refer to them as a compass for making decisions.

9.

Practice “systems thinking out loud”

Sometimes, demonstrating your thinking process can be even more valuable than providing a ready-made answer. Instead of hiding your thoughts, structure your thoughts, showing a methodical approach to solving the problem.

“Let us look at this problem systematically. First, we need to understand what factors affect the situation, then identify possible scenarios and finally choose the optimal strategy of action.”

10.

Develop “intellectual modesty”

Paradoxically, recognizing the limits of your knowledge can strengthen, not weaken, your position as an expert. In today’s world of information overload, the ability to say “I don’t know, but I’ll find out” is perceived as a manifestation of intellectual honesty and maturity.

Research in the field of leadership psychology shows that leaders who demonstrate “intellectual modesty” (the ability to recognize the limitations of their knowledge) gain more trust in subordinates and make more informed decisions in the long run.

Conclusion: Confidence as a Practical Skill

The ability to look confident is not an innate characteristic, but a set of specific techniques and skills that can be developed and improved. By applying the methods described above, you will not only create an image of a competent professional, but will actually become more effective in situations of uncertainty.

Remember, the goal is not to pretend to be an all-knowing expert, but to create a space of security and trust where you and your team can work productively to find optimal solutions. Real confidence comes not from the illusion of omniscience, but from a comfortable attitude to the unknown and a belief in one’s ability to find a way forward even in the most difficult situations.

Glossary of terms

Halo effect

Cognitive distortion, in which the overall impression of a person affects the perception of his individual qualities. For example, a confident person is often perceived as more competent and reliable.

Framing.

A psychological technique that involves creating a context or “framework” of perception for subsequent information to influence how that information is interpreted.

Power poses

Open, extended body positions, which researchers have linked to increased testosterone levels and lower cortisol levels, leading to feelings of greater power and less stress.

Empathic leadership

A leadership style based on understanding and considering the emotional needs and motivations of team members.

Intellectual modesty

Ability to recognize the limitations of your knowledge and be open to new information and points of view, even if they contradict existing beliefs.

Systems thinking

An approach to analysis in which objects are viewed as systems of interconnected elements rather than isolated units. It allows you to see not only individual problems, but also their interrelations in a broader context.

What is the scarcity effect and why do you buy what you don’t need?

What a young person needs to understand in order to be successful in society