320

Exit from the Karpman Triangle

409050

Description

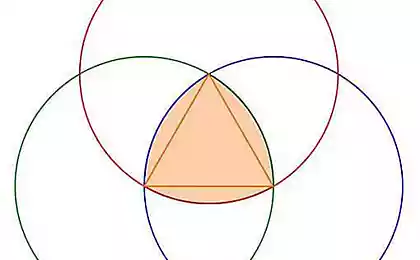

Many people have noticed that the same conflicts are repeated in a similar scenario: someone is constantly “forever guilty”, another “saves the situation”, and a third blames or suppresses. In psychology, this interaction is described. Carpman's dramatic triangleThe participants play the roles of Victim, Persecutor and Rescuer. This model explains why conflicts can last indefinitely, and that each of the participants derives its hidden benefits by supporting the drama.

What if you find yourself in a destructive scenario and want to break the cycle? In this article, we will look at the origin of the concept of the Karpman triangle, analyze its roles and their interaction, give life examples and, most importantly, give practical recommendations and exercises that will help to get out of this vicious circle of “drama”.

Historic excursion

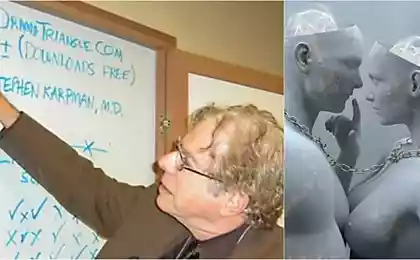

Concept Carpman triangle It originated in the late 1960s as part of the Transactional Analysis School. The author of the model is an American psychiatrist and psychologist Stephen KarpmanA student of the famous Eric Berne (the creator of the theory of transactional analysis). In 1968, Karpman published Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis, where he first described this socio-psychological model of human interaction. Initially, he called it the “triangle of fate”, but later the model became known as the “dramatic triangle of Karpman” (Karpman Triangle – Wikipedia).

Karpman clearly demonstrated his idea on examples of fairy tales. For example, in the fairy tale about Red Riding Hood, the characters successively change roles: Red Riding Hood first acts as a Rescuer (carries pies to a sick grandmother), then becomes a Victim of the Wolf, the Wolf – the Persecutor, later a hunter appears as a new “Rescuer”, turning the Wolf into a Victim, and in the finale, Red Riding Hood herself takes revenge on the Wolf, acting as the Persecutor. This example showed how dynamically roles can change within a single story. Karpman’s model quickly caught the attention of psychologists because it described typical dramatic interactions in a simple way. Today, the Karpman Triangle is widely used in popular psychology to analyze conflicts and codependent relationships.

Roles in the Karpman Triangle and Their Interaction

The dramatic triangle includes three key roles that can unconsciously play out in a conflict situation:

Important: None of these roles contributes to a real solution. Each player in the triangle tends to satisfy their hidden needs (attention, control, recognition) rather than end the conflict. Therefore, a conflict situation can escalate again and again, while all three are firmly stuck in these positions.

Examples of the Karpman Triangle in Life

Let’s look at a few situations that show how the Karpman triangle manifests itself in real relationships:

Family example: In a strict family, the father can act as the Persecutor – constantly scold and punish the child for misdeeds. At the same time, the child feels offended by the Victim, trying to earn love, but feels helplessness and fear of the father. The mother, seeing the suffering of the child, assumes the role of the Rescuer: she protects the baby, calms him, and at the same time condemns the father for excessive severity. In this drama, everyone benefits: the father asserts his power, the mother – a sense of need and moral superiority, and the child – attention and release from responsibility. However, the real family conflict is not solved, but only preserved in these roles.

An example in a relationship: In a pair of two people, the triangle of drama can also manifest itself, even without the “third extra”. Imagine a quarrel: one partner feels misunderstood and hurt (the victim) and complains about his condition. The second, tired after a hard day, reacts irritatedly: accuses the first of excessive sensitivity and “inflating the problem”, becoming the Persecutor. The conflict heats up, and after a while the first partner (in the role of the Victim) goes into aggression – for example, remembers old grievances and attacks in response, turning into the Persecutor, and the second at this moment feels like a Victim and may even try to make amends, comforting the partner (in the role of the Rescuer). In a short time, the roles rotate several times in a circle, but the quarrel itself is not resolved constructively unless both are aware of the game.

A working example: The Karpman triangle is often found in the collective. For example, the new head of the department constantly criticizes the subordinate for minor mistakes and puts inflated plans – this is a classic Persecutor. The subordinate tries at first, but soon gives up, feeling injustice: he begins to perceive himself as a victim of circumstances, works without enthusiasm, and complains to colleagues about the boss. In the meantime, another employee may take on the role of a Rescuer – for example, trying to help that subordinate with his tasks or comfort him by agreeing that the boss is behaving incorrectly. As a result, instead of openly discussing disagreements, the trio “boss – employee – good colleague” gets bogged down in the game: the boss is increasingly angry at the drop in results, the employee goes deeper into the role of the offended victim, and the colleague – “rescuer” is torn between work and other people’s problems. This situation can last for months until someone leaves the role.

How to get out of the Karpman triangle: practical recommendations

Once you’ve become part of a dramatic triangle (whether in a family, relationship, or job), it’s important to take steps to get out of this scenario. Here are some practical tips to help break the cycle of roles:

Over time, as you practice new patterns of behavior, you will notice that dramatic triangles occur less and less. Every time you successfully avoid being drawn into a familiar role, it’s a step toward a healthier and more honest relationship. Remember that it is possible to leave the Karpman triangle from any position if you deliberately refuse to play the previously chosen role.

Conclusion

The Karpman Triangle is a powerful metaphor for understanding the nature of many protracted conflicts and emotionally charged “games” between people. Although this concept originated as part of the theory of transactional analysis and does not claim to be a universal scientific explanation of all conflicts, it has proved extremely useful in everyday life. By recognizing the roles of the Victim, Persecutor and Rescuer in our relationship, we get a chance to break the cycle of mutual grievances and disappointments. Instead of unconsciously playing a role, one can choose to act consciously: take responsibility for oneself, respect the boundaries of others, and jointly seek solutions to problems.

Leaving the Karpman Triangle is a path to a more mature position in life. By rejecting drama and manipulation, we learn direct communication and genuine cooperation. This is not easy and takes time, because the usual scenarios can be deeply rooted. However, by practicing mindfulness and new reactions, you can gradually transform dramatic relationships into healthy ones. Ultimately, such an exit improves the quality of life: conflicts are resolved more effectively, and relationships are built on trust and respect, without games and masks.

Glossary of terms

The Karpman Triangle (Dramatic Triangle)

A psychological model of interaction that describes the three roles (Victim, Persecutor, Rescuer) that people unconsciously play in conflict situations. The concept was proposed by Stephen Karpman in 1968.

Victim

One of the roles in the Karpman Triangle. The person in the victim position feels oppressed, powerless and seeks support, avoiding responsibility for solving the problem.

Persecutor (Aggressor)

A role in a dramatic triangle characterized by accusation, criticism, or aggression. The Persecutor suppresses the Victim in an effort to gain power or vent irritation, but does not seek to constructively resolve the problem.

Lifeguard.

A role in a triangle in which a person intervenes in a conflict under the pretext of helping the victim. The Rescuer acts from a “hero” position, but his help is intrusive and keeps the Victim dependent instead of actually resolving the situation.

Transaction analysis

Psychotherapy and Communication Theory, founded by Eric Berne. It considers human interactions as a series of “transactions” and highlights typical scenarios (games), one of which is a dramatic triangle.

Codependency

A type of relationship in which one person is overly dependent on another emotionally or psychologically, often sacrificing their own needs. Codependent relationships often fuel the Karpman triangle (e.g., the "victim" and "rescuer" in a pair may be codependent).

Leaving the triangle

The process of refusing to participate in a dramatic triangle. It involves recognizing one’s role, changing one’s habitual reactions and moving to a more constructive, open interaction without playing the roles of Victim, Persecutor or Rescuer.

Description

Many people have noticed that the same conflicts are repeated in a similar scenario: someone is constantly “forever guilty”, another “saves the situation”, and a third blames or suppresses. In psychology, this interaction is described. Carpman's dramatic triangleThe participants play the roles of Victim, Persecutor and Rescuer. This model explains why conflicts can last indefinitely, and that each of the participants derives its hidden benefits by supporting the drama.

What if you find yourself in a destructive scenario and want to break the cycle? In this article, we will look at the origin of the concept of the Karpman triangle, analyze its roles and their interaction, give life examples and, most importantly, give practical recommendations and exercises that will help to get out of this vicious circle of “drama”.

Historic excursion

Concept Carpman triangle It originated in the late 1960s as part of the Transactional Analysis School. The author of the model is an American psychiatrist and psychologist Stephen KarpmanA student of the famous Eric Berne (the creator of the theory of transactional analysis). In 1968, Karpman published Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis, where he first described this socio-psychological model of human interaction. Initially, he called it the “triangle of fate”, but later the model became known as the “dramatic triangle of Karpman” (Karpman Triangle – Wikipedia).

Karpman clearly demonstrated his idea on examples of fairy tales. For example, in the fairy tale about Red Riding Hood, the characters successively change roles: Red Riding Hood first acts as a Rescuer (carries pies to a sick grandmother), then becomes a Victim of the Wolf, the Wolf – the Persecutor, later a hunter appears as a new “Rescuer”, turning the Wolf into a Victim, and in the finale, Red Riding Hood herself takes revenge on the Wolf, acting as the Persecutor. This example showed how dynamically roles can change within a single story. Karpman’s model quickly caught the attention of psychologists because it described typical dramatic interactions in a simple way. Today, the Karpman Triangle is widely used in popular psychology to analyze conflicts and codependent relationships.

Roles in the Karpman Triangle and Their Interaction

The dramatic triangle includes three key roles that can unconsciously play out in a conflict situation:

- Victim. The main position is “poor me!”. The person in the role of the Victim feels oppressed, helpless and hurt. He believes that control over the situation is beyond his control. The victim refuses to take responsibility for what is happening and tends to blame circumstances or other people for their troubles. Such a person often complains about his fate and looks for someone who will “save him” instead of actively seeking a solution to the problem.

- Persecutor. Position: "It's all your fault!" The persecutor is the aggressor and accuser. He criticizes, punishes, or intimidates the Victim to gain a sense of power and control. In this role, the person expresses anger and displeasure, often exaggerating the mistakes of the victim. The persecutor believes he is right and uses attack or sarcasm to assert his superiority. However, despite the seeming desire to “teach” the guilty, the Persecutor does not offer a constructive solution to the problem.

- Rescue. Position: “Let me help you!” The Rescuer seeks to help the Victim, even if she did not ask for it. At first glance, the Rescuer’s motivation is noble – he wants to solve the problem and support the weak. But deep down, it is important for the Rescuer to feel its importance and irreplaceability. He unwittingly encourages the helplessness of the victim, because then you can continue to save her and receive gratitude. It is important to understand that rescue is not the same as real help. The rescuer intervenes out of need, not because circumstances really require it.

Important: None of these roles contributes to a real solution. Each player in the triangle tends to satisfy their hidden needs (attention, control, recognition) rather than end the conflict. Therefore, a conflict situation can escalate again and again, while all three are firmly stuck in these positions.

Examples of the Karpman Triangle in Life

Let’s look at a few situations that show how the Karpman triangle manifests itself in real relationships:

Family example: In a strict family, the father can act as the Persecutor – constantly scold and punish the child for misdeeds. At the same time, the child feels offended by the Victim, trying to earn love, but feels helplessness and fear of the father. The mother, seeing the suffering of the child, assumes the role of the Rescuer: she protects the baby, calms him, and at the same time condemns the father for excessive severity. In this drama, everyone benefits: the father asserts his power, the mother – a sense of need and moral superiority, and the child – attention and release from responsibility. However, the real family conflict is not solved, but only preserved in these roles.

An example in a relationship: In a pair of two people, the triangle of drama can also manifest itself, even without the “third extra”. Imagine a quarrel: one partner feels misunderstood and hurt (the victim) and complains about his condition. The second, tired after a hard day, reacts irritatedly: accuses the first of excessive sensitivity and “inflating the problem”, becoming the Persecutor. The conflict heats up, and after a while the first partner (in the role of the Victim) goes into aggression – for example, remembers old grievances and attacks in response, turning into the Persecutor, and the second at this moment feels like a Victim and may even try to make amends, comforting the partner (in the role of the Rescuer). In a short time, the roles rotate several times in a circle, but the quarrel itself is not resolved constructively unless both are aware of the game.

A working example: The Karpman triangle is often found in the collective. For example, the new head of the department constantly criticizes the subordinate for minor mistakes and puts inflated plans – this is a classic Persecutor. The subordinate tries at first, but soon gives up, feeling injustice: he begins to perceive himself as a victim of circumstances, works without enthusiasm, and complains to colleagues about the boss. In the meantime, another employee may take on the role of a Rescuer – for example, trying to help that subordinate with his tasks or comfort him by agreeing that the boss is behaving incorrectly. As a result, instead of openly discussing disagreements, the trio “boss – employee – good colleague” gets bogged down in the game: the boss is increasingly angry at the drop in results, the employee goes deeper into the role of the offended victim, and the colleague – “rescuer” is torn between work and other people’s problems. This situation can last for months until someone leaves the role.

How to get out of the Karpman triangle: practical recommendations

Once you’ve become part of a dramatic triangle (whether in a family, relationship, or job), it’s important to take steps to get out of this scenario. Here are some practical tips to help break the cycle of roles:

- Recognize the “game” and your role. The first step is to see the pattern itself. Ask yourself: What role do I play in a conflict? Victims, Rescuer or Persecutor? Being aware of your position is already half the success. Remember that you can get out of any of these roles if you stop playing along with the script.

- Voluntarily give up the role. Decide not to support destructive drama anymore. It means you stop doing what you did automatically. If you are constantly complaining and waiting for help, try to take a break and not look for a lifeguard. If you used to scold and criticize, stop and change the tone. If you saved everyone around you, realize that you do not have to solve other people’s problems. You have the right to quit the game.

- Take responsibility for yourself. The key to liberation is to start taking responsibility for your needs and actions without passing them on to others. It’s important for the victim to recognize that only she can change her situation—for example, asking for help directly or changing her behavior instead of waiting for mercy. The rescuer should honestly look at their motives and understand that obsessive help is a desire to feel their worth. The persecutor must accept that aggression only exacerbates the conflict and seek other ways to express his feelings.

- Change your communication style. Try to get out of the habitual reaction and find a constructive solution to the conflict. Instead of complaining or complaining, go to open dialogue. Talk about your feelings and needs calmly, without reproach. Instead of rescuing or attacking, ask, “How can we solve this problem?” Direct communication destroys the triangle scenario because you stop playing roles and start looking for a way out together.

- Set healthy boundaries. This is especially true for chronic rescuers and victims. Learn to refuse when you are not ready or able to help – there is nothing wrong with that. If you tend to be a Victim, practice directly expressing your desires and discontents without expecting others to “guess” themselves. If you are a rescuer by nature, ask yourself: “Do you really need this help or did I not ask for it?” The ability to say “no” and state your needs helps you avoid getting involved in unhealthy games.

- Look for hidden benefits and replace them with healthy alternatives. Analyze the psychological benefits you (and others) get from staying in the triangle. Perhaps the Victim avoids responsibility or gets attention in this way, the Rescuer is a sense of self-worth, and the Persecutor is an outlet for his anger and power complex. Once you understand these ulterior motives, think about how to satisfy them more constructively. For example, the need for recognition can be met through achievement in work or creativity, rather than through the role of perpetual sufferer. The thirst for control and respect is best realized by becoming a leader in a good way—inspiring, not suppressing. And the desire to help others should be channeled into mentoring or support on request, rather than compulsively “saving” everyone.

Over time, as you practice new patterns of behavior, you will notice that dramatic triangles occur less and less. Every time you successfully avoid being drawn into a familiar role, it’s a step toward a healthier and more honest relationship. Remember that it is possible to leave the Karpman triangle from any position if you deliberately refuse to play the previously chosen role.

Conclusion

The Karpman Triangle is a powerful metaphor for understanding the nature of many protracted conflicts and emotionally charged “games” between people. Although this concept originated as part of the theory of transactional analysis and does not claim to be a universal scientific explanation of all conflicts, it has proved extremely useful in everyday life. By recognizing the roles of the Victim, Persecutor and Rescuer in our relationship, we get a chance to break the cycle of mutual grievances and disappointments. Instead of unconsciously playing a role, one can choose to act consciously: take responsibility for oneself, respect the boundaries of others, and jointly seek solutions to problems.

Leaving the Karpman Triangle is a path to a more mature position in life. By rejecting drama and manipulation, we learn direct communication and genuine cooperation. This is not easy and takes time, because the usual scenarios can be deeply rooted. However, by practicing mindfulness and new reactions, you can gradually transform dramatic relationships into healthy ones. Ultimately, such an exit improves the quality of life: conflicts are resolved more effectively, and relationships are built on trust and respect, without games and masks.

Glossary of terms

The Karpman Triangle (Dramatic Triangle)

A psychological model of interaction that describes the three roles (Victim, Persecutor, Rescuer) that people unconsciously play in conflict situations. The concept was proposed by Stephen Karpman in 1968.

Victim

One of the roles in the Karpman Triangle. The person in the victim position feels oppressed, powerless and seeks support, avoiding responsibility for solving the problem.

Persecutor (Aggressor)

A role in a dramatic triangle characterized by accusation, criticism, or aggression. The Persecutor suppresses the Victim in an effort to gain power or vent irritation, but does not seek to constructively resolve the problem.

Lifeguard.

A role in a triangle in which a person intervenes in a conflict under the pretext of helping the victim. The Rescuer acts from a “hero” position, but his help is intrusive and keeps the Victim dependent instead of actually resolving the situation.

Transaction analysis

Psychotherapy and Communication Theory, founded by Eric Berne. It considers human interactions as a series of “transactions” and highlights typical scenarios (games), one of which is a dramatic triangle.

Codependency

A type of relationship in which one person is overly dependent on another emotionally or psychologically, often sacrificing their own needs. Codependent relationships often fuel the Karpman triangle (e.g., the "victim" and "rescuer" in a pair may be codependent).

Leaving the triangle

The process of refusing to participate in a dramatic triangle. It involves recognizing one’s role, changing one’s habitual reactions and moving to a more constructive, open interaction without playing the roles of Victim, Persecutor or Rescuer.

Erich Fromm: The fate of people is a consequence of their unmade choice.

Detoxification from drugs by AMOD: modern approaches to the treatment of addiction