312

China’s Growth Model: Was Ricardo Right?

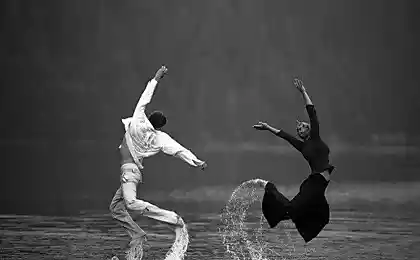

Ullens Center for Contemporary Art

History knows many economic miracles, of which in the end nothing worked. The economist Georg von Walwitz analyzes the history of China, where economic growth became possible because his government did not fall for the “Ricardian trick”, according to which it is enough just to open borders, how well-being will grow by itself. However, funding through real estate prices could cause this bubble to burst soon.

What about the classics teachings today? Ricardo occupies a prominent place in the canon of classical economics. Everyone knows that it meant something, it is mentioned in all textbooks, but the specifics in this knowledge are rare, because, to be exact, Ricardo, unlike Adam Smith, was important only for the nineteenth century, and cultural historians sometimes get an unkind feeling that he was interesting only insofar as Marx wrote off much of him. But it would be wrong to say that one dead dog supports the life of the other, it is unfair to both and, moreover, completely ignores their fundamentally different approach to the world: one wanted to change the world, the other wanted something from it. But both are still important mainly for the century before last, for in the twentieth century the state of science went so far that in ordinary texts they are found only in footnotes, and there they occupy a completely undeserved place. They should be credited with being defenseless in the face of their supporters (in Marx’s case they were adherents of the Soviet system) or opponents (in other words, the position of the Keynesian school in relation to the classics) who caused them such damage, after which there was really little left of them. But as it happens, history has mistreated both, and the camps of their followers have been curtseying to this day out of a sense of duty rather than an inner conviction, more to create the history and depth of their own tradition than to draw the attention of contemporaries to their ideas.

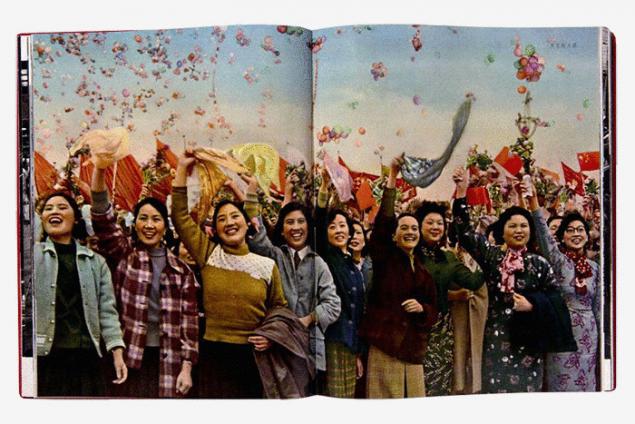

How dead both dogs are can be judged by the Chinese growth model. After the Cultural Revolution, China found itself in a heap of economic and moral ruins and had to start over. In the person of Deng Xiaoping, China had a leader who in many battles and wars thoroughly studied all the heights and depths of life and in his old age became a pragmatist. He no longer wanted to appeal to Marx, but he did not appeal to Ricardo’s ideas either, since he was indifferent to systems in principle.

© Bruno Barbey

© Bruno Barbey

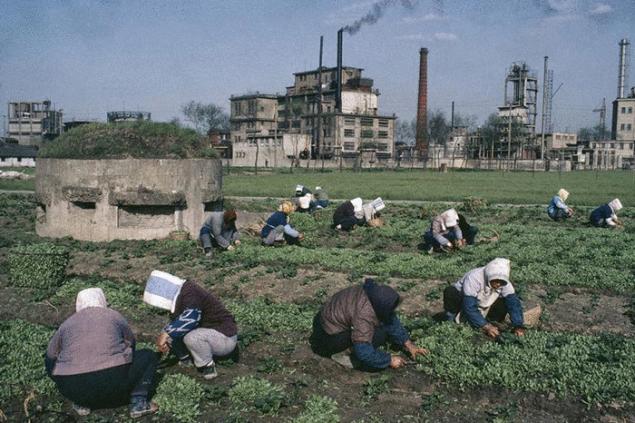

The Chinese model, launched by Deng, focuses largely on ideas opposed to Ricardo. The theory of comparative advantage, by which the British forced the Portuguese to exchange precious wine for cheap canvas, did not seem promising to Deng Xiaoping. It may have made sense for a while to exchange agricultural products for manufactured products, but it would never have been very wise to adhere to this, for it would have meant that industrialization remained confined to a few countries. China was much more willing to follow the advice of Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Treasury Secretary, who, in a landmark speech before Congress in 1791, advocated a shift from agriculture to industry, and did not want to be content with a static distribution of comparative advantages. Advantages can be earned by your work, just as you can lose them. Hamilton argued that industrial labor should be stimulated, because industry provides useful things—weapons and machinery—and is more productive than agriculture. She does not know the forced breaks associated with dependence on daylight or season, and thanks to the introduction of machinery, many jobs can also be done by women and children who have had too much free time up to now. Therefore, industrial society creates the highest prosperity, and it would be foolish to remain for a long time only an exporter of wheat and cotton. The United States had to make an effort to build its own industry, which would not be inferior to the English, and the state had to play an active role, not just to watch what was happening. China does not want to serve as a tool in the hands of industrialized nations for a long time and remain a waiter where it can become a host. The poor state in which China was in the late 1970s convinced Deng Xiaoping not to be too scrupulous in choosing an economic model and not to be afraid of Hamiltonian advertising of child labor and weapons production (both then considered the result of good intentions). Since then, China has been trying to close the gap. Free trade, which Ricardo considered as a source of general prosperity, is, in the eyes of the Chinese planner, rather a means of suppression by which the West tries to secure for itself the advantage gained by historical accident. China does not want to serve as a tool in the hands of industrialized nations for a long time and remain a waiter where it can become a host. The profit of Foxconn, which collects iPhones, iPads, Kindles, tablets, game consoles, etc., is a quarter of what its customer receives. He who invents products, who puts them on the market and sells them, makes money. Whoever builds them can be replaced. Wealth – together with most of the added value – remains with the customer.

In order to break free from this situation, China allowed Marx and Ricardo to become the “good guys” and acts like this. The easiest exercise is currency manipulation. The authorities argued that the Chinese financial system, as in any developing country, is unstable and therefore it is necessary to control the inflow and outflow of money. A pleasant side effect is the ability to keep the exchange rate of one’s own currency low and thereby make production in one’s own country cheap and consumption of foreign products expensive. If domestic goods are cheap and popular, and foreign roads, then people work more and spend less, that is, they are in a Calvinist paradise. Germany did this after World War II and became the world champion in exports thanks to the low value of the German mark in the 1950s. Those who produce the cheapest of all can weave a network of factories one string at a time, and obtain a greater part of the added value within the country. The Chinese did it on the model of the Germans, until they – like the Germans in their day – were branded as manipulators by the generally patient US. And the Chinese could no longer hide behind their backwardness. Then easy profits were left behind, and it became more difficult to hinder free trade.

Deng Xiaoping and his wife Zhou Lin

With so many industries now in the country, and with them special knowledge, the most natural course was to steal intellectual property—after all, we knew what to do with it. At this stage of development, China also relied on the United States and Germany, which at the beginning of the XIX century looked at England and learned to borrow the best ideas there. He who can no longer and does not want to produce only cheaply must have better goods, and to do so he must use ideas which cannot be produced by himself. Involuntarily, you have to look at the market leaders, and as a result, the models of young Chinese car companies are still similar to Volkswagen. But sooner or later, even the most good-natured trade partner unravels these tricks and complains to the government, which, although gradually, allegedly out of good intentions, still recommends its industry in the production of goods to rely more on domestic culture.

In parallel, the argument of Infant-Industry (minor industry), also put into circulation by Alexander Hamilton and fixed in a theoretical concept by the Württemberg economist Friedrich List (1789-1846), is given. These are protective customs duties for the young industry, which needs special protection of the state, because it is still small and weak. To expose it to the cruel logic of the market would be heartless and directly hostile to progress, for how can a gentle sprout break through the jungle? There, the larger ones do not allow the smaller ones to grow, and those who want to allow new ideas to evolve must give them air to breathe and light to live. And thus, to protect the weak, which in itself sounds pleasant to hear, protective customs duties are introduced - not to enrich the state or harm foreigners, nothing of which no one officially thought. Tariffs will remain in place until Chinese businesses achieve technological or price leadership. However, this wait may last for a long time, with which foreign countries will be powerless to reconcile and be content with those segments of the market that the government will open for real competition.

But there's a problem. It is not enough to subsidize your industry as long as it seems vulnerable and protect it from competition. She gets fed up and lethargic long before she achieves anything noticeable, sits comfortably in her hammock and feels surrounded by a safety net of state favor (as was recently the case with the German solar panel industry, a favorite child of politicians). Therefore, the trick with protective customs duties too often does not work if these duties cloud the spirit of the entrepreneur, and dogs have to be carried on the hunt. We must not allow the fence against external competition to lead to the fact that there would be no competition at all. If, for example, a market leader develops that is large enough to outperform all domestic competitors but too sluggish to be capable of international competition, then the grants are simply donated money. The national competition must be ruthless.

All big firms get cheap money from state-owned banks, where the Chinese are forced – because of capital controls – to put their money at grotesquely low interest rates. In China (semi-)public enterprises are encouraged by the state as much as possible. The glass industry gets its raw materials for a pittance, the automotive industry suppliers get steel and technology not much more expensive (US$28 billion has been spent on subsidies in a decade since 2001). The paper industry received $33 billion in subsidies between 2002 and 2009. And so on. Not only are old state-owned enterprises receiving this friendly support, but also new private firms such as Geely Automobile (2011 subsidies: $141 million) or China Yurun Food ($84 million). All large firms receive cheap money from state-owned banks, where the Chinese are forced – because of capital controls – to put their money at a grotesquely low interest rate (far below the rate of inflation); thus, these subsidies are not reflected in official statistics, but transferred directly from the population to enterprises.

© Bruno Barbey

© Bruno Barbey

What subsidies can turn into is illustrated by Wuhan Iron & Steel, China’s fourth-largest steelmaker, which relied on many good friends in the party and state and could always count on a helping hand, even though the firm has long since emerged from “childhood.” Its business model has quietly changed, and while it still makes steel, it has found that it can actually save effort by focusing on what it does best: attracting subsidies. Wuhan Iron & Steel decided to invest $4.7 billion in pork. A firm like Wuhan is doing very well in different areas, and a lot of government aid is going to agriculture. In such a situation, what could be more logical than diversification towards land cultivation and animal husbandry? However, this is not about efficiency or expertise, and this is not done to improve the welfare of China, and is justified only by the benefit of the company and its shareholders. This is what the government can get when it indulges its firms too much. G. Valvitz refers to the pragmatic advice of the entrepreneur Lopahin to break the cherry orchard into suburban areas in order to avoid ruin, which the heroes of Chekhov’s play did not want to listen to.

By the way, the Germans did it much better after World War II. Innumerable medium-sized companies were in a merciless competition, which forced enterprises to constantly renew their equipment and production process. This is how the cost-comprehension culture developed, which was further strengthened in the next phase of the continuous revaluation of the German mark and which is a huge advantage in global competition today. In China, management often thinks too much about how to get close to subsidies, whereas in Germany, the product comes first, and state aid is usually just the icing on the cake. So many firms are used to their subsidies and protective customs duties, and no one in the government has learned the lesson from the Cherry Orchard about how hard it is to part with privilege.

But what the Chinese know better than the Germans is how to handle salaries that rise before the country is actually in the first league. After the war, West Germany was able to keep wages low, because before the construction of the Wall, the constant influx of migrants from the East made sure that the unemployed were always enough. In doing so, the country followed Smith and Ricardo’s teaching that low wages are a boon to economic growth and strengthen international competitiveness. But China, like the United States in the nineteenth century, has for several years abandoned the use of new untrained workers from the uncivilized western provinces for cheap produce. A 25 percent pay rise like Foxconn's in 2012 is not seen as a weakening of competitiveness. China sees such development as positive, as forcing industry to become more competitive through innovation and as a means of stimulating domestic consumption, without which the economy cannot have medium-term growth. The country is trying to balance demand growth between consumption and investment, which not only sounds reasonable, but is inevitable, given China’s size and population. But the transition to a less export-dependent and more domestically-based economy will not be easy.

© Bruno Barbey

So, by these means, which contradict Ricardo’s whole doctrine of free trade and poverty wages, China is trying to restructure its economy away from agriculture and toward much more productive industries in order to raise the country’s material standard of living to a decent level. And this is natural, because history has treated poorly the attempts to achieve prosperity through the unconditional openness of markets. Only commercial cities such as Singapore and Hong Kong have succeeded.

The spectacle of the eurozone in recent years may have strengthened the Chinese in their growth model. In Europe there is complete freedom of trade, or at least something very close to it. The enthusiasm with which Latin European countries rushed to the EU, blinded by the promise of economic respectability and low interest rates on loans, turned into pure madness, which lasted for a decade, and then turned into total discord and distrust. These countries have fallen victim to what we would call a Ricardian trick: they have bought into the argument that it is enough to open borders, and prosperity will grow by itself. The Germans – let’s call the entire northern middle of Europe from Vienna to Helsinki – only noticed how great their advantages of monetary union were when it was too late for everyone else to change. What Happens to a Monetary Union in a Free Trade Area? Industry is concentrated where it has a comparative advantage. Where there are skilled workers, reasonable wages, good infrastructure, legal guarantees and a network of suppliers. It would not occur to anyone to set up a chemical or automobile plant in Greece, Portugal or southern Italy if it could be built in Baden-Württemberg. The only bargaining chips that less developed countries have at their disposal – customs tariffs, subsidies, currency devaluation – are not available in the eurozone (and the more valuable they are to the Chinese). In Germany, for example, productivity is high because there is industrial production, and in Latin Europe prosperity arises only as an illusion, on loans, for a short time. Comparative advantages are established once and for all, Latinos can compete with the Germans only through radical innovation or significant transfer payments. But both are implausible.

The advantages of large concerns, privileges for party members and the weak development of private institutions cause at least some distrust among the outside observer. The Chinese did not fall for the Ricardian stunt. They chose the classical teaching and relied more on historical experience. So far, they have done well, but their unconventional growth model has its limits. If they do not soon find an export market that is permanently ready for acceptance, in some measure equivalent to the Latin European market for the German economy, they must be prepared for the fact that the part of the economy that produces investment goods will soon suffer severe losses. If growth falls from 10% to 6% per year (which is plausible), investment will fall from 50% of GDP to 30%. But then something will affect the shortage of 20% of GDP, which will not be so easy to replace out of nothing. The whole system at the moment stimulates investment, banks give loans, the party and the state give land, subsidies and protection from competition. But the returns from this are less and less, the dollars invested today will bring clearly less profit than they brought a decade ago.

© Bruno Barbey

© Bruno Barbey

But there may soon be another problem in China. The financial system has taken a form there that will not last long. The richest percentage of the population controls a fortune of about $2,000 billion, which corresponds to about two-thirds of the huge foreign exchange reserves. Land prices have risen enormously in cities, from 1,000 yuan in 2002 to 3,130 yuan a decade later (the national average). Households on the booming East Coast are now worth twice as much in places as in London and have quadrupled in the past five years. In China, much is financed through real estate prices, through loans secured by these extravagant prices. An outside observer would not be surprised if this bubble bursts one day. As we marvel at the wonder of China’s growth model, we thus keep in mind that there have been many economic miracles in history that have failed to produce anything. The advantages of the large concerns, the privileges of the party members, and the weak development of private institutions cause at least some distrust among the outside observer, no less than among the Communist Party of China the teachings of Ricardo and Marx. published

An excerpt from the new history of the development of economic ideas "Mr. Smith and the Paradise of Earth." Invention of Welfare, published by Ad Marginem with the participation of the Garage Museum.

P.S. And remember, just changing our consumption – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru