311

Dora Nass: Learning to recognize evil before it becomes invincible

As a warning - a German citizen's story about how fascism began when "the country fell ill with megalomania." Dora Nass (née Pettin) was seven years old at the time and remembers how Hitler’s dictatorship was established.

Dora Nass in her Berlin apartment

I was born in 1926 near Potsdamerplatz and lived on the Koenigetserstrasse. This street is next to the Wilhelmstrasse, where were all the ministries of the Third Reich and the residence of Hitler himself. I often go there and remember how it all started and how it ended. And I think it wasn't yesterday or even five minutes ago, it's happening right now. I have very poor eyesight and hearing, but everything that happened to me, to us, when Hitler came to power, both during the war and in its last months, I can see and hear perfectly. I can’t see your face clearly, only fragments. But my mind is still working. I hope (laughs).

Do you remember how you and your loved ones reacted when Hitler came to power?

Do you know what happened in Germany before 1933? Chaos, crisis, unemployment. There are homeless people on the streets. Many went hungry. Inflation is such that my mother took a bag of money to buy bread. Not figurative. A real little bag of money. It seemed to us that this horror would never end.

And suddenly there is a man who stops the fall of Germany into the abyss. I remember very well how excited we were in the early years of his reign. People got jobs, roads were built, poverty was gone.

And now, remembering our admiration, how we and my friends and friends praised our Fuhrer, how we were ready to wait for hours for his speech, I would like to say this: we must learn to recognize evil before it becomes invincible. We failed and we paid such a price! And forced others to pay.

Didn't think... My father died when I was eight months old. My mother was completely apolitical. Our family had a restaurant in central Berlin. When SA officers came to our restaurant, everyone avoided them. They behaved like an aggressive gang, like proletarians who gained power and want to recoup their years of slavery.

Not only were there Nazis in our school, some teachers didn't join the party. Until November 9, 1938, we did not feel how serious everything was (on the night of November 9, 1938, Jewish pogroms began in Germany (Kristallnacht). About a hundred Jews were killed and 26,000 sent to concentration camps.

But that morning we saw glass broken in Jewish-owned shops. And everywhere the inscriptions are “Jewish shop”, “Don’t buy from Jews”. That morning we realized that something bad was beginning. But none of us knew the extent of the crime.

You see, there's so much money right now to find out what's really going on. Back then, almost no one had a phone, rarely anyone had a radio, and there was nothing to say about television. Hitler and his ministers spoke on the radio. And they are in the papers. I read newspapers every morning because they were lying for customers in our restaurant. There was no mention of deportation or the Holocaust. My friends didn’t even read newspapers.

Of course, when our neighbors disappeared, we could not help but notice that they were in a labor camp. Nobody talked about the death camps. And if we did, we didn’t believe it. A camp where people are killed? No way. Few bloody and strange rumors do not happen in war.

Foreign politicians came to us and nobody criticized Hitler’s policies. Everyone shook his hand. We agreed on cooperation. What were we thinking?

Thousands of Dora’s peers were members of the National Socialist Union of German Girls.

Did you and your friends talk about war?

In 1939, we had no idea what kind of war we were waging. And even then, when the first refugees arrived, we didn't really think about what it meant and where it would lead. We had to feed them, clothe them and shelter them. Of course, we could not have imagined that war would come to Berlin. What can I say? Most people don’t use the mind, as it has been before.

Do you think you didn’t use your mind at the time?

(After a pause.) Yeah, I didn't think about a lot, I didn't understand. I didn't want to understand. And now, when I listen to recordings of Hitler’s speeches—in some museum, for example—I always think, oh my God, how strange and scary what he says, and I, young, was among those who stood under the balcony of his residence and shouted with delight.

It is very difficult for a young person to resist the general flow, to think what all this means, to try to predict what this might lead to. At the age of ten, I, like thousands of other girls of my age, joined the National Socialist Union of German Girls. We had parties, we cared for the old people, we traveled, we went out together, we had holidays. The summer solstice, for example. Bonfires, songs, joint work for the good of Greater Germany. In short, we were organized on the same principle as the pioneers in the Soviet Union.

In my class there were girls and boys whose parents were Communists or Social Democrats. They banned their children from participating in Nazi holidays. And my brother was a little boss in the Hitler Youth. And he said: if someone wants to join our organization, please, if not, we will not force. But there were other little Fuehrers who said, Whoever is not with us is against us. And they were very aggressive towards those who refused to take part in the common cause.

Pastors in uniform My friend Helga lived right on the Wilhelmstrasse. Hitler’s car was often accompanied by five cars. And one day her toy got under the wheels of the Fuehrer's car. He ordered her to stop, let her come and get a toy from under the wheels, and he got out of the car and patted her on the head. Helga still tells this story, I would say, not without awe (laughs).

Or, for example, in the building of the Ministry of Air Transport, which was headed by Goering, a gym was built for him. And my friend, who knew someone from the ministry, could safely go to Goering's personal gym. And she was let through, and no one searched her, no one checked her bag.

We felt like we were all a big family. You can't pretend that all this didn't happen.

And then there was the madness — the megalomaniac disease of the whole country. And that was the beginning of our disaster. And when German-friendly politicians came to the Anhalter Banhof station, we ran to meet them. I remember seeing Mussolini when he came. What about? Was it possible to miss the Duce's arrival? It is difficult for you to understand, but every time has its heroes, its delusions and its myths. Now I am wiser, I can say that I was wrong, that I should have thought deeper, but then? In this atmosphere of universal excitement and conviction, reason ceases to play a role. By the way, when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, we were sure that the USSR was not our enemy.

Did you not expect war in 1941?

We did not expect the war to start so soon. After all, all the rhetoric of the Fuehrer and his ministers was that the Germans needed land in the east. And every day on the radio, from newspapers, from speeches - everything spoke of our greatness. Great Germany, Great Germany, Great Germany. How much of Germany is missing! The average person has the same logic: my neighbor has a Mercedes, and I only have a Volkswagen. I'm better than my neighbor. Then I want more and more, more and more. This is not to say that most of us are believers.

Destroyed Berlin. 1945.

There was a church near my house, but our priest never talked about the party or Hitler. He wasn't even in the party. However, I have heard that in some other parishes, pastors perform in uniform! And they say from the pulpit almost the same as the Fuehrer himself says! They were fanatical Nazi pastors.

There were pastors who fought against Nazism. They were sent to camps.

Did textbooks say that the German race is superior?

I will now show you my school textbook (the 1936 school textbook is being pulled from the bookshelf). I keep everything: my textbooks, my daughter’s textbooks, my late husband’s things – I love not only the history of the country, but also my small, private history. Here's a 1936 textbook. I am ten years old. Read one of the texts. Please, out loud.

Der Fuhrer Kommt (The Coming of the Fuhrer) Today, Adolf Hitler will arrive by plane. Little Reinhold really wants to see him. He asks his father and mother to go with him to meet the Fuhrer. They walk together. Many people have already gathered at the airport. And everyone misses little Reinhold: "You're small - go ahead, you must see the Fuehrer!" ? The plane with Hitler appeared in the distance. The music is playing, everyone freezes in admiration, and the plane has landed and everyone cheers on the Fuehrer! Little Reinhold exclaims, “He’s here!” He's here! Heil Hitler! Unable to stand the delight, Reinhold runs to the Fuehrer. He notices the baby, smiles, takes the hand and says, “It’s good that you came!” ? Reinhold is happy. He'll never forget that. Now I am laughing and bitter to read, but then these texts seemed to me completely normal.

We went to anti-Semitic movies, to Suess Jew, for example (Fite Harlan’s anti-Semitic film Suess Jew was made on Goebbels’ personal orders in 1940 to justify the open persecution of Jews – The New Times). This film proved that the Jews were greedy, dangerous, that they were one evil, that our cities should be liberated from them as soon as possible.

Propaganda is a terrible force. The scariest. I recently met a woman my age. She's lived in the GDR all her life. She has so many stereotypes about the West Germans! He talks about us and thinks about us. It wasn’t until she met me that she began to realize that West Germans were just people, not the most greedy and arrogant, but simply people. How many years have passed since the union? And we belong to the same people, but even in this case the prejudices instilled by propaganda are so tenacious.

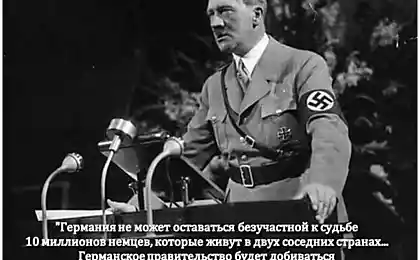

Adolf Hitler delivers a speech at the Kroll Opera House to Reichstag deputies regarding Franklin D. Roosevelt’s remarks.

Photo by kotenikkote.wordpress.com

I don’t understand how people can be divided by nationality. I am an old man, and now it seems to me that everything is so simple: if someone has much, he should share it; that one should not despise or even dislike a person for being a different nation. But I'm not going to give you a moral report [laughs]. As a young man, I heard so many times that the Slavic race is an inferior race. How could you believe that?

You believed?

When the leaders of the country tell you the same thing every day, and you are a teenager. Yes, I did. I didn't know a Slav, a Pole or a Russian. In 1942, I went from Berlin to work in a small Polish village. We all worked without pay and a lot.

Did you live in occupied territory?

Yeah. The Poles were evicted from there, and the Germans, who had lived in Ukraine before, arrived. My names were Emma and Emil, very good people. Good family. German was spoken as well as Russian. I lived there for three years. Even though it was obvious in 1944 that we were losing the war, I still felt very well in that village because I was doing good for the country and living among good people.

Were you concerned that people who used to live there were kicked out of this village?

I didn't think about it. Now it is probably difficult, even impossible to understand...

Where the train goes

Dora Nass after the war

In January 1945, I had an appendicitis attack. The disease, of course, found time! (Laughs) I was lucky to be sent to the hospital and operated on. The chaos was already beginning, our troops were leaving Poland, and because I was given medical care, it was a miracle. After the operation, I lay there for three days. We, the sick, were evacuated.

We didn't know where our train was going. They only understood the direction - we are going west, we are fleeing the Russians. Sometimes the train stopped and we didn’t know if it would go any further. If I had my papers on the train, the consequences could be terrible. They may ask me why I am not where my country sent me. Why not at the farm? Who let me go? Who cares if I'm sick? There was so much fear and chaos that I could be shot.

But I wanted to go home. Just go home. Mommy. Finally, the train stopped near Berlin in the city of Uckermünde. And that's where I got off. An unknown woman, a nurse, seeing my condition, with unhealed stitches, with an almost open wound that was constantly ill, bought me a ticket to Berlin. And I met my mom.

And a month later, still ill, I went to Berlin to get a job. So strong was fear! I could not leave my Germany and my Berlin at such a moment.

It is strange for you to hear this about faith and fear, but I assure you that if a Russian man of my age heard me, he would perfectly understand what I am talking about.

I worked in the tram park until April 21, 1945. That day, Berlin was being bombarded like never before. And again, without asking anyone's permission, I ran away. Weapons were scattered in the streets, tanks were burning, the wounded were screaming, corpses were lying, the city was beginning to die, and I did not believe that I was walking in my Berlin ... it was a very different, terrible place ... it was a dream, a terrible dream ... I didn’t go near anyone, I didn’t help anyone, I walked like an enchanted man to where my house was.

And on April 28, my mother, my grandfather and I went down to the bunker because the Soviet army had begun to take Berlin. My mom took one thing with her, a small cup. And until she died, she only drank from that cracked, dimmed cup. When I left home, I brought my favorite leather bag. I was wearing a watch and a ring, and that was all I had left of my past life.

So we went down to the bunker. There was no step to step - people around, toilets do not work, a terrible stench ... No one has food or water.

Suddenly among us, hungry and frightened, a rumor spreads: units of the German army have taken up positions in the north of Berlin and are beginning to retake the city! And everyone has such hope! We decided at all costs to break through to our army. Can you imagine? It was obvious that we had lost the war, but we still believed that victory was possible.

And my grandfather and I, who were supported on both sides, went through the subway to the north of Berlin. But we did not walk long - soon it turned out that the subway was flooded. There was knee-deep water. The three of us stood there, and there was darkness and water. Upstairs are Russian tanks. And we decided not to go anywhere, but just hide under the platform. We were lying there and just waiting.

On May 3, Berlin surrendered. When I saw the ruins, I couldn’t believe it was my Berlin. I thought it was a dream and I was about to wake up. We went looking for our house. When we got to the place where he was standing, we saw the ruins.

Russian soldier

Boris Abdulguzhin. 1945.

Then we started looking for a roof over our heads and settled in a dilapidated house. Having settled there somehow, they left the house and sat on the grass.

Suddenly we noticed a wagon in the distance. There was no doubt that these were Russian soldiers. Of course, I was horribly frightened when the wagon stopped and a Soviet soldier went in our direction. And suddenly he spoke German! In very good German!

That's how the world began for me. He sat next to us and we talked for a long time. He told me about his family and I told him about mine. And we were both so glad there was no more war! There was no hatred, no fear of a Russian soldier. I gave him my picture and he gave me his. In the photo was written his postal front number.

He lived with us for three days. And I put a little sign on the house where we lived, "Occupied by tank crews." He saved our homes and maybe our lives. Because we would have been kicked out of a livable home, and there's no telling what would have happened to us next. I remember meeting him as a miracle. He was a man in an inhuman time.

I want to stress in particular: there was no romance. It was impossible to even think about it in that situation. What a novel! We were supposed to just survive. Of course, I met other Soviet soldiers. For example, a man in military uniform suddenly approached me, sharply tore my bag from my hands, threw it to the ground and immediately, right in front of me, urinated on it.

We heard rumors about what Soviet soldiers were doing to German women, and we were very afraid of them. Then we found out what our troops were doing in the USSR. My meeting with Boris and the way he behaved was a miracle. On May 9, 1945, Boris never came back. And then I spent many decades looking for him, and I wanted to say thank you for what he did. I wrote to your government, to the Kremlin, to the secretary general, and invariably received either silence or rejection.

After Gorbachev came to power, I felt that I had a chance to find out if Boris was alive, and if so, to find out where he lives and what happened to him, and maybe even to meet him! But under Gorbachev, the same answer came to me again and again: the Russian army does not open its archives.

And only in 2010, a German journalist conducted an investigation and learned that Boris died in 1984, in the Bashkir village, where he lived all his life. I never saw him again.

The journalist met with his children, who are now adults, and they said that he talked about meeting me and told the children: learn German.

In Russia, I read, nationalism is rising, right? It's so weird. And I read that you have less and less freedom, that there is propaganda on television. I wish our mistakes would not be repeated by the people who liberated us. I see your victory in 1945 as liberation. You liberated the Germans. And now, when I read about Russia, it seems that the state is very bad and the people are very good. How do you say that? Muterchen Russland, "Mother Russia" (with an accent, in Russian), right? I know this from my brother, who returned from Russian captivity in 1947. He said that in Russia he was treated as a human being, that he was even treated, although he could not. But they did it, they spent their time on captivity and medicine, and he was always grateful for it. He went to the front as a young man - he, like many other young men, took advantage of politicians. But then he realized that the guilt of the Germans was enormous. We have unleashed the worst war and are responsible for it. There can be no other opinions.

Was it the “German guilt” of an entire nation? As far as I know, this idea has long met with resistance in German society.

I can't tell you all about the people... But I've often wondered, how did this become possible? Why did this happen? And could we have stopped it? And what can one person do if he knows the truth, if he understands what nightmare everyone is walking so cheerfully?

And I also ask, why are we allowed to have such power? Was it not clear from the rhetoric, promises, curses and appeals of our leaders what was going on? I remember the 1936 Olympics (the Summer Olympics were held in Berlin in August 1936). Shortly before them, in February 1936, Germany hosted the Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Bavarian Alps) and the Winter Olympics — no one said a word against Hitler, and the international sports delegations that walked through the stadium greeted Hitler with Nazi salutes. Nobody knew how it would end, not even politicians. And now, I'm just grateful for every day. It's a gift. I thank God every day that I am alive and that I have lived the life he gave me. Thank you for meeting my husband and having a son. My husband and I moved into the apartment where we are talking now, in the fifties. After the cramped, dilapidated houses where we lived, it was happiness! Two rooms! Separate bath and toilet! It was a palace! See the picture on the wall? That's my husband. He's old here. We're sitting with him in a cafe in Vienna - he laughs at me: "Dora, you're filming me again." This is my favorite picture. He's happy here. He has a cigarette in his hand, I eat ice cream, and the day is so sunny. And every night, as I walk past this picture, I say to him, "Good night, Franz!" And when I wake up, "Good morning!" You see, I framed Albert Schweitzer's saying, "The only trace we can leave in this life is a trace of love." And it's incredible that a journalist from Russia came to me, we're talking and I'm trying to explain to you how I felt and how other Germans felt when they were mad and won, and then when our country was destroyed by your troops, and how Russian soldier Boris saved me and my family. What would I write in my journal today if I could see it? That a miracle happened today. The interview was first published in The New Times on 11.03.2013. Shortly after the publication of Dore Nass, a letter arrived in Berlin: Dear Mrs. Dora Nass!

Writes to you from distant Russia, the Republic of Bashkortostan, the granddaughter of Bakhtiyar Abdulguzhin, known to you by the name of Boris, Guzalia Abdulguzhina. My father's name is Akram, son of Bakhtiar. We, our family and relatives thank you for bringing back good memories of our grandfather over the years. At home, we highly appreciate the actions, courage and heroism of a person.

Unfortunately, I was not meant to see my grandfather. He passed away on March 18, 1984, and I was born in 1989. But I thought I knew him alive. Because my father always told us about him, what he was like, what rewards he had. We saw him as a hero. Every time we were asked to write an essay on “My Grandfather” in school, we wrote about it with great pride. At home we have, as I remember myself, his belongings (documents, records, medals and other things), wrapped in a white rag. We took care of it and were even afraid to touch it, and looked only from the hands of our father. I thought that was all that was left of my grandfather. But I was wrong, it turns out, the most valuable thing is to hear kind words about him. No matter how many years have passed. After the article “The country fell ill with megalomania” appeared, our journalists contacted us. They wrote about him in the newspapers, made a radio broadcast, and the goal was that no matter how difficult times were, humanity and kindness are always above all else. Yes, indeed, our grandfather was so fair, kind and human. This is our pride and the most precious thing.

According to my father’s stories, my grandfather told me about you and showed me a picture of you that we still have today. He always said, “Learn German.” As we know, the German people are distinguished by their cleanliness and European culture. That's what Grandpa kept at home. He died before reaching his 60th birthday. All his life he worked as a foreman of the construction team of his native village. In the postwar years, houses were built and kolkhoz was raised. Married, he has seven children. Unfortunately, my grandmother died very early, even before my grandfather died. Six daughters and one son, my dad. The eldest daughter was born in 1948 and the youngest was born in 1962. They all live in different parts of our country. We live in my grandfather’s home village. They built a new house instead.

Unfortunately, he did not live to see these days. He'd be glad. And if there were as many opportunities as there are now (for example, the Internet), maybe you would meet, at least through the Internet. I think he never forgot about you because he kept your picture, not that it was just preserved.

On behalf of my parents, on behalf of all the children of my grandfather, I wish you and your family health, happiness and long life. May good people always surround you! Thank you so much!

Abdulguzhina Guzalia Akramovna, Russia, Republic of Bashkortostan

FRAU NASS:

Dear Guzalia!

It was hard not to cry while reading your letter - deep and bold. I strongly invite you to visit Berlin – I will show you the places where my relatives and I hid from the bombings and from the Soviet troops. I'll show you where your grandfather saved us. I hope you will not be offended if I offer to pay a part of the cost of airfare to you and any of your relatives who may want to go with you. I'm so sorry I couldn't meet Boris. But I hope I can see you. This will be a very important meeting for me.

I'll see you in Berlin. Dora Nass. published

Author Arthur Solomonov, translated by Katya Kollman

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: asiarussia.ru/persons/7548/

Dora Nass in her Berlin apartment

I was born in 1926 near Potsdamerplatz and lived on the Koenigetserstrasse. This street is next to the Wilhelmstrasse, where were all the ministries of the Third Reich and the residence of Hitler himself. I often go there and remember how it all started and how it ended. And I think it wasn't yesterday or even five minutes ago, it's happening right now. I have very poor eyesight and hearing, but everything that happened to me, to us, when Hitler came to power, both during the war and in its last months, I can see and hear perfectly. I can’t see your face clearly, only fragments. But my mind is still working. I hope (laughs).

Do you remember how you and your loved ones reacted when Hitler came to power?

Do you know what happened in Germany before 1933? Chaos, crisis, unemployment. There are homeless people on the streets. Many went hungry. Inflation is such that my mother took a bag of money to buy bread. Not figurative. A real little bag of money. It seemed to us that this horror would never end.

And suddenly there is a man who stops the fall of Germany into the abyss. I remember very well how excited we were in the early years of his reign. People got jobs, roads were built, poverty was gone.

And now, remembering our admiration, how we and my friends and friends praised our Fuhrer, how we were ready to wait for hours for his speech, I would like to say this: we must learn to recognize evil before it becomes invincible. We failed and we paid such a price! And forced others to pay.

Didn't think... My father died when I was eight months old. My mother was completely apolitical. Our family had a restaurant in central Berlin. When SA officers came to our restaurant, everyone avoided them. They behaved like an aggressive gang, like proletarians who gained power and want to recoup their years of slavery.

Not only were there Nazis in our school, some teachers didn't join the party. Until November 9, 1938, we did not feel how serious everything was (on the night of November 9, 1938, Jewish pogroms began in Germany (Kristallnacht). About a hundred Jews were killed and 26,000 sent to concentration camps.

But that morning we saw glass broken in Jewish-owned shops. And everywhere the inscriptions are “Jewish shop”, “Don’t buy from Jews”. That morning we realized that something bad was beginning. But none of us knew the extent of the crime.

You see, there's so much money right now to find out what's really going on. Back then, almost no one had a phone, rarely anyone had a radio, and there was nothing to say about television. Hitler and his ministers spoke on the radio. And they are in the papers. I read newspapers every morning because they were lying for customers in our restaurant. There was no mention of deportation or the Holocaust. My friends didn’t even read newspapers.

Of course, when our neighbors disappeared, we could not help but notice that they were in a labor camp. Nobody talked about the death camps. And if we did, we didn’t believe it. A camp where people are killed? No way. Few bloody and strange rumors do not happen in war.

Foreign politicians came to us and nobody criticized Hitler’s policies. Everyone shook his hand. We agreed on cooperation. What were we thinking?

Thousands of Dora’s peers were members of the National Socialist Union of German Girls.

Did you and your friends talk about war?

In 1939, we had no idea what kind of war we were waging. And even then, when the first refugees arrived, we didn't really think about what it meant and where it would lead. We had to feed them, clothe them and shelter them. Of course, we could not have imagined that war would come to Berlin. What can I say? Most people don’t use the mind, as it has been before.

Do you think you didn’t use your mind at the time?

(After a pause.) Yeah, I didn't think about a lot, I didn't understand. I didn't want to understand. And now, when I listen to recordings of Hitler’s speeches—in some museum, for example—I always think, oh my God, how strange and scary what he says, and I, young, was among those who stood under the balcony of his residence and shouted with delight.

It is very difficult for a young person to resist the general flow, to think what all this means, to try to predict what this might lead to. At the age of ten, I, like thousands of other girls of my age, joined the National Socialist Union of German Girls. We had parties, we cared for the old people, we traveled, we went out together, we had holidays. The summer solstice, for example. Bonfires, songs, joint work for the good of Greater Germany. In short, we were organized on the same principle as the pioneers in the Soviet Union.

In my class there were girls and boys whose parents were Communists or Social Democrats. They banned their children from participating in Nazi holidays. And my brother was a little boss in the Hitler Youth. And he said: if someone wants to join our organization, please, if not, we will not force. But there were other little Fuehrers who said, Whoever is not with us is against us. And they were very aggressive towards those who refused to take part in the common cause.

Pastors in uniform My friend Helga lived right on the Wilhelmstrasse. Hitler’s car was often accompanied by five cars. And one day her toy got under the wheels of the Fuehrer's car. He ordered her to stop, let her come and get a toy from under the wheels, and he got out of the car and patted her on the head. Helga still tells this story, I would say, not without awe (laughs).

Or, for example, in the building of the Ministry of Air Transport, which was headed by Goering, a gym was built for him. And my friend, who knew someone from the ministry, could safely go to Goering's personal gym. And she was let through, and no one searched her, no one checked her bag.

We felt like we were all a big family. You can't pretend that all this didn't happen.

And then there was the madness — the megalomaniac disease of the whole country. And that was the beginning of our disaster. And when German-friendly politicians came to the Anhalter Banhof station, we ran to meet them. I remember seeing Mussolini when he came. What about? Was it possible to miss the Duce's arrival? It is difficult for you to understand, but every time has its heroes, its delusions and its myths. Now I am wiser, I can say that I was wrong, that I should have thought deeper, but then? In this atmosphere of universal excitement and conviction, reason ceases to play a role. By the way, when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, we were sure that the USSR was not our enemy.

Did you not expect war in 1941?

We did not expect the war to start so soon. After all, all the rhetoric of the Fuehrer and his ministers was that the Germans needed land in the east. And every day on the radio, from newspapers, from speeches - everything spoke of our greatness. Great Germany, Great Germany, Great Germany. How much of Germany is missing! The average person has the same logic: my neighbor has a Mercedes, and I only have a Volkswagen. I'm better than my neighbor. Then I want more and more, more and more. This is not to say that most of us are believers.

Destroyed Berlin. 1945.

There was a church near my house, but our priest never talked about the party or Hitler. He wasn't even in the party. However, I have heard that in some other parishes, pastors perform in uniform! And they say from the pulpit almost the same as the Fuehrer himself says! They were fanatical Nazi pastors.

There were pastors who fought against Nazism. They were sent to camps.

Did textbooks say that the German race is superior?

I will now show you my school textbook (the 1936 school textbook is being pulled from the bookshelf). I keep everything: my textbooks, my daughter’s textbooks, my late husband’s things – I love not only the history of the country, but also my small, private history. Here's a 1936 textbook. I am ten years old. Read one of the texts. Please, out loud.

Der Fuhrer Kommt (The Coming of the Fuhrer) Today, Adolf Hitler will arrive by plane. Little Reinhold really wants to see him. He asks his father and mother to go with him to meet the Fuhrer. They walk together. Many people have already gathered at the airport. And everyone misses little Reinhold: "You're small - go ahead, you must see the Fuehrer!" ? The plane with Hitler appeared in the distance. The music is playing, everyone freezes in admiration, and the plane has landed and everyone cheers on the Fuehrer! Little Reinhold exclaims, “He’s here!” He's here! Heil Hitler! Unable to stand the delight, Reinhold runs to the Fuehrer. He notices the baby, smiles, takes the hand and says, “It’s good that you came!” ? Reinhold is happy. He'll never forget that. Now I am laughing and bitter to read, but then these texts seemed to me completely normal.

We went to anti-Semitic movies, to Suess Jew, for example (Fite Harlan’s anti-Semitic film Suess Jew was made on Goebbels’ personal orders in 1940 to justify the open persecution of Jews – The New Times). This film proved that the Jews were greedy, dangerous, that they were one evil, that our cities should be liberated from them as soon as possible.

Propaganda is a terrible force. The scariest. I recently met a woman my age. She's lived in the GDR all her life. She has so many stereotypes about the West Germans! He talks about us and thinks about us. It wasn’t until she met me that she began to realize that West Germans were just people, not the most greedy and arrogant, but simply people. How many years have passed since the union? And we belong to the same people, but even in this case the prejudices instilled by propaganda are so tenacious.

Adolf Hitler delivers a speech at the Kroll Opera House to Reichstag deputies regarding Franklin D. Roosevelt’s remarks.

Photo by kotenikkote.wordpress.com

I don’t understand how people can be divided by nationality. I am an old man, and now it seems to me that everything is so simple: if someone has much, he should share it; that one should not despise or even dislike a person for being a different nation. But I'm not going to give you a moral report [laughs]. As a young man, I heard so many times that the Slavic race is an inferior race. How could you believe that?

You believed?

When the leaders of the country tell you the same thing every day, and you are a teenager. Yes, I did. I didn't know a Slav, a Pole or a Russian. In 1942, I went from Berlin to work in a small Polish village. We all worked without pay and a lot.

Did you live in occupied territory?

Yeah. The Poles were evicted from there, and the Germans, who had lived in Ukraine before, arrived. My names were Emma and Emil, very good people. Good family. German was spoken as well as Russian. I lived there for three years. Even though it was obvious in 1944 that we were losing the war, I still felt very well in that village because I was doing good for the country and living among good people.

Were you concerned that people who used to live there were kicked out of this village?

I didn't think about it. Now it is probably difficult, even impossible to understand...

Where the train goes

Dora Nass after the war

In January 1945, I had an appendicitis attack. The disease, of course, found time! (Laughs) I was lucky to be sent to the hospital and operated on. The chaos was already beginning, our troops were leaving Poland, and because I was given medical care, it was a miracle. After the operation, I lay there for three days. We, the sick, were evacuated.

We didn't know where our train was going. They only understood the direction - we are going west, we are fleeing the Russians. Sometimes the train stopped and we didn’t know if it would go any further. If I had my papers on the train, the consequences could be terrible. They may ask me why I am not where my country sent me. Why not at the farm? Who let me go? Who cares if I'm sick? There was so much fear and chaos that I could be shot.

But I wanted to go home. Just go home. Mommy. Finally, the train stopped near Berlin in the city of Uckermünde. And that's where I got off. An unknown woman, a nurse, seeing my condition, with unhealed stitches, with an almost open wound that was constantly ill, bought me a ticket to Berlin. And I met my mom.

And a month later, still ill, I went to Berlin to get a job. So strong was fear! I could not leave my Germany and my Berlin at such a moment.

It is strange for you to hear this about faith and fear, but I assure you that if a Russian man of my age heard me, he would perfectly understand what I am talking about.

I worked in the tram park until April 21, 1945. That day, Berlin was being bombarded like never before. And again, without asking anyone's permission, I ran away. Weapons were scattered in the streets, tanks were burning, the wounded were screaming, corpses were lying, the city was beginning to die, and I did not believe that I was walking in my Berlin ... it was a very different, terrible place ... it was a dream, a terrible dream ... I didn’t go near anyone, I didn’t help anyone, I walked like an enchanted man to where my house was.

And on April 28, my mother, my grandfather and I went down to the bunker because the Soviet army had begun to take Berlin. My mom took one thing with her, a small cup. And until she died, she only drank from that cracked, dimmed cup. When I left home, I brought my favorite leather bag. I was wearing a watch and a ring, and that was all I had left of my past life.

So we went down to the bunker. There was no step to step - people around, toilets do not work, a terrible stench ... No one has food or water.

Suddenly among us, hungry and frightened, a rumor spreads: units of the German army have taken up positions in the north of Berlin and are beginning to retake the city! And everyone has such hope! We decided at all costs to break through to our army. Can you imagine? It was obvious that we had lost the war, but we still believed that victory was possible.

And my grandfather and I, who were supported on both sides, went through the subway to the north of Berlin. But we did not walk long - soon it turned out that the subway was flooded. There was knee-deep water. The three of us stood there, and there was darkness and water. Upstairs are Russian tanks. And we decided not to go anywhere, but just hide under the platform. We were lying there and just waiting.

On May 3, Berlin surrendered. When I saw the ruins, I couldn’t believe it was my Berlin. I thought it was a dream and I was about to wake up. We went looking for our house. When we got to the place where he was standing, we saw the ruins.

Russian soldier

Boris Abdulguzhin. 1945.

Then we started looking for a roof over our heads and settled in a dilapidated house. Having settled there somehow, they left the house and sat on the grass.

Suddenly we noticed a wagon in the distance. There was no doubt that these were Russian soldiers. Of course, I was horribly frightened when the wagon stopped and a Soviet soldier went in our direction. And suddenly he spoke German! In very good German!

That's how the world began for me. He sat next to us and we talked for a long time. He told me about his family and I told him about mine. And we were both so glad there was no more war! There was no hatred, no fear of a Russian soldier. I gave him my picture and he gave me his. In the photo was written his postal front number.

He lived with us for three days. And I put a little sign on the house where we lived, "Occupied by tank crews." He saved our homes and maybe our lives. Because we would have been kicked out of a livable home, and there's no telling what would have happened to us next. I remember meeting him as a miracle. He was a man in an inhuman time.

I want to stress in particular: there was no romance. It was impossible to even think about it in that situation. What a novel! We were supposed to just survive. Of course, I met other Soviet soldiers. For example, a man in military uniform suddenly approached me, sharply tore my bag from my hands, threw it to the ground and immediately, right in front of me, urinated on it.

We heard rumors about what Soviet soldiers were doing to German women, and we were very afraid of them. Then we found out what our troops were doing in the USSR. My meeting with Boris and the way he behaved was a miracle. On May 9, 1945, Boris never came back. And then I spent many decades looking for him, and I wanted to say thank you for what he did. I wrote to your government, to the Kremlin, to the secretary general, and invariably received either silence or rejection.

After Gorbachev came to power, I felt that I had a chance to find out if Boris was alive, and if so, to find out where he lives and what happened to him, and maybe even to meet him! But under Gorbachev, the same answer came to me again and again: the Russian army does not open its archives.

And only in 2010, a German journalist conducted an investigation and learned that Boris died in 1984, in the Bashkir village, where he lived all his life. I never saw him again.

The journalist met with his children, who are now adults, and they said that he talked about meeting me and told the children: learn German.

In Russia, I read, nationalism is rising, right? It's so weird. And I read that you have less and less freedom, that there is propaganda on television. I wish our mistakes would not be repeated by the people who liberated us. I see your victory in 1945 as liberation. You liberated the Germans. And now, when I read about Russia, it seems that the state is very bad and the people are very good. How do you say that? Muterchen Russland, "Mother Russia" (with an accent, in Russian), right? I know this from my brother, who returned from Russian captivity in 1947. He said that in Russia he was treated as a human being, that he was even treated, although he could not. But they did it, they spent their time on captivity and medicine, and he was always grateful for it. He went to the front as a young man - he, like many other young men, took advantage of politicians. But then he realized that the guilt of the Germans was enormous. We have unleashed the worst war and are responsible for it. There can be no other opinions.

Was it the “German guilt” of an entire nation? As far as I know, this idea has long met with resistance in German society.

I can't tell you all about the people... But I've often wondered, how did this become possible? Why did this happen? And could we have stopped it? And what can one person do if he knows the truth, if he understands what nightmare everyone is walking so cheerfully?

And I also ask, why are we allowed to have such power? Was it not clear from the rhetoric, promises, curses and appeals of our leaders what was going on? I remember the 1936 Olympics (the Summer Olympics were held in Berlin in August 1936). Shortly before them, in February 1936, Germany hosted the Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Bavarian Alps) and the Winter Olympics — no one said a word against Hitler, and the international sports delegations that walked through the stadium greeted Hitler with Nazi salutes. Nobody knew how it would end, not even politicians. And now, I'm just grateful for every day. It's a gift. I thank God every day that I am alive and that I have lived the life he gave me. Thank you for meeting my husband and having a son. My husband and I moved into the apartment where we are talking now, in the fifties. After the cramped, dilapidated houses where we lived, it was happiness! Two rooms! Separate bath and toilet! It was a palace! See the picture on the wall? That's my husband. He's old here. We're sitting with him in a cafe in Vienna - he laughs at me: "Dora, you're filming me again." This is my favorite picture. He's happy here. He has a cigarette in his hand, I eat ice cream, and the day is so sunny. And every night, as I walk past this picture, I say to him, "Good night, Franz!" And when I wake up, "Good morning!" You see, I framed Albert Schweitzer's saying, "The only trace we can leave in this life is a trace of love." And it's incredible that a journalist from Russia came to me, we're talking and I'm trying to explain to you how I felt and how other Germans felt when they were mad and won, and then when our country was destroyed by your troops, and how Russian soldier Boris saved me and my family. What would I write in my journal today if I could see it? That a miracle happened today. The interview was first published in The New Times on 11.03.2013. Shortly after the publication of Dore Nass, a letter arrived in Berlin: Dear Mrs. Dora Nass!

Writes to you from distant Russia, the Republic of Bashkortostan, the granddaughter of Bakhtiyar Abdulguzhin, known to you by the name of Boris, Guzalia Abdulguzhina. My father's name is Akram, son of Bakhtiar. We, our family and relatives thank you for bringing back good memories of our grandfather over the years. At home, we highly appreciate the actions, courage and heroism of a person.

Unfortunately, I was not meant to see my grandfather. He passed away on March 18, 1984, and I was born in 1989. But I thought I knew him alive. Because my father always told us about him, what he was like, what rewards he had. We saw him as a hero. Every time we were asked to write an essay on “My Grandfather” in school, we wrote about it with great pride. At home we have, as I remember myself, his belongings (documents, records, medals and other things), wrapped in a white rag. We took care of it and were even afraid to touch it, and looked only from the hands of our father. I thought that was all that was left of my grandfather. But I was wrong, it turns out, the most valuable thing is to hear kind words about him. No matter how many years have passed. After the article “The country fell ill with megalomania” appeared, our journalists contacted us. They wrote about him in the newspapers, made a radio broadcast, and the goal was that no matter how difficult times were, humanity and kindness are always above all else. Yes, indeed, our grandfather was so fair, kind and human. This is our pride and the most precious thing.

According to my father’s stories, my grandfather told me about you and showed me a picture of you that we still have today. He always said, “Learn German.” As we know, the German people are distinguished by their cleanliness and European culture. That's what Grandpa kept at home. He died before reaching his 60th birthday. All his life he worked as a foreman of the construction team of his native village. In the postwar years, houses were built and kolkhoz was raised. Married, he has seven children. Unfortunately, my grandmother died very early, even before my grandfather died. Six daughters and one son, my dad. The eldest daughter was born in 1948 and the youngest was born in 1962. They all live in different parts of our country. We live in my grandfather’s home village. They built a new house instead.

Unfortunately, he did not live to see these days. He'd be glad. And if there were as many opportunities as there are now (for example, the Internet), maybe you would meet, at least through the Internet. I think he never forgot about you because he kept your picture, not that it was just preserved.

On behalf of my parents, on behalf of all the children of my grandfather, I wish you and your family health, happiness and long life. May good people always surround you! Thank you so much!

Abdulguzhina Guzalia Akramovna, Russia, Republic of Bashkortostan

FRAU NASS:

Dear Guzalia!

It was hard not to cry while reading your letter - deep and bold. I strongly invite you to visit Berlin – I will show you the places where my relatives and I hid from the bombings and from the Soviet troops. I'll show you where your grandfather saved us. I hope you will not be offended if I offer to pay a part of the cost of airfare to you and any of your relatives who may want to go with you. I'm so sorry I couldn't meet Boris. But I hope I can see you. This will be a very important meeting for me.

I'll see you in Berlin. Dora Nass. published

Author Arthur Solomonov, translated by Katya Kollman

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: asiarussia.ru/persons/7548/

Fat, not “cubes” and fitness, created modern civilization

A Sanskrit scholar Durga Prasad Shastri: do You speak a modified form of Sanskrit!