571

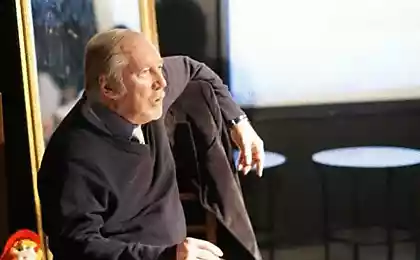

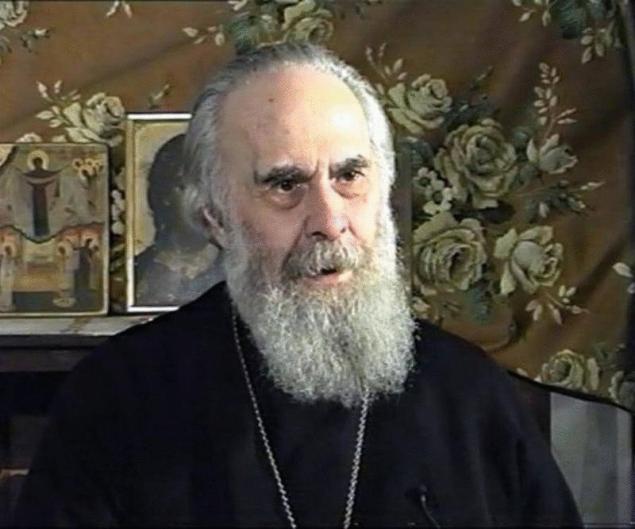

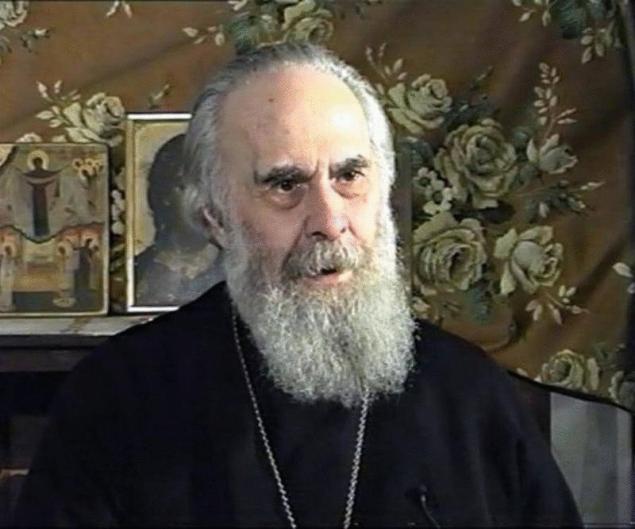

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. In a world of chaos, death, suffering, evil, incompleteness...

The modern world presents us with a challenge, and the world is modern for every generation at any time in life. But sometimes it is worth thinking about what a challenge is and what a challenge we face.

Every generation faces change. For some, change means a certain degree of bewilderment: what was previously self-evident, what seemed reliable, gradually disintegrates or is called into question, often in a very radical way, violently. For others, change is a different kind of uncertainty: young people enter a changing world and do not know where it will lead them. Thus, both groups – those who think that the old world is collapsing, disappearing, changing beyond recognition, and those who find themselves in a world that is itself becoming, the shape of which they cannot understand, can not see – face the same challenge, but in different ways. And I'd like to present you two or three images and my own conclusions, because the only thing you can do about your life is to share what you've learned or what you think is true.

All of us, as a rule, expect that everything in life should be safe, harmonious, peaceful, without problems, that life should develop like a well-groomed plant grows from a seed: a small sprout under cover gradually reaches its full bloom. But we know from experience that this is not the case. It seems to me that God is the God of tempest, just as He is the God of harmony and peace. And the first image that comes to mind is the Gospel story of Christ walking on the sea in the midst of a storm and Peter trying to come to Him in the waves (Matthew 14:22-34).

Let us leave aside the historical aspect of the story. What happened here, what does that tell us? Christ did not calm the storm by the mere fact of His presence. And this seems important to me, because all too often, when we are caught by a storm, whether it is small or great, we tend to think that a storm has broken out, so God is not here, so something is wrong (usually with God, less often with us). And secondly, since Christ can be in the middle of a storm and not be hesitant, broken, destroyed, it means that He is in equilibrium. And in a hurricane, in a tornado, in any storm, the point of stability, the point where all the raging forces of the elements collide, balancing themselves, is at the very heart of the hurricane; and here God is. Not at the edge, not where He could safely go out on land while we are drowning in the sea, He is where the situation is worst, where the raging, the most confrontation.

If we recall the story of Peter walking on water, we see that his impulse was correct. Peter saw that he was in mortal danger. The small boat in which he is, can sink, it can break the waves, turn the raging wind. And in the midst of the storm, he saw the Lord in His marvelous peace, and he realized that if he could reach that point himself, he too would be at the heart of the storm—and yet in untold peace. And he was ready to leave the safety of the boat, which represented protection from the storm, albeit fragile, but still protection (other disciples were saved in it), and go out into the storm. He could not reach the Lord because he remembered that he might drown. He began to think about himself, about the storm, about the fact that he had never yet walked on the waves, he turned to himself and could no longer rush to God. He lost the safety of the boat and did not find the complete safety of the place where the Lord was.

And it seems to me that when we think of ourselves in the modern world (and, as I said, the world is modern from generation to generation, there is no time when the world is not the same storm, only to each generation it is presented in a different guise), we all face the same problem: the small boat provides some protection, everything is fraught with danger, in the center of the storm is the Lord, and the question arises: Am I ready to go to Him? This is the first image, and I let everyone respond to it on their own.

The second image that comes to mind is the act of creation. The first line of the Bible says that God created heaven and earth (Genesis 1:1). When I think about it, this is what I think. God, the fullness of everything, harmony, beauty, summons by name all possible creatures. He calls, and every creature rises from nothingness, from complete, radical absence, rises in primordial harmony and beauty, and the first thing she sees is the complete, perfect beauty of God, the first thing she perceives is complete harmony in the Lord. And the name of this harmony is love, dynamic, creative love. This is what we express when we say that the perfect image of the relationship of love is found in the Trinity.

But if we think about the next lines, or rather the second half of the sentence, we see something that should make us think about our situation. It says that the first call of God created what in Hebrew is called chaos, chaos, chaos, out of which God causes objects, forms, realities. The Bible uses different words when referring to the primary act of creating this chaos (what it is, I will try to define it now) and when referring to further creation. In the first case, a word is used that speaks of creation out of nothing that was not, in the second, of the creation of something out of, so to speak, already existing material.

Chaos is always thought of as disorder, disorganized being. We think of the chaos in our room, implying that the room has to be cleaned and we've turned it all over. When we think of chaos on the larger scale of life, in the world, we think of a city that has been bombarded, or a society where competing interests clash, where love has faded or disappeared, where nothing is left but greed, egocentrism, fear, hatred, etc. We understand chaos as a situation where what should be harmonious, has lost harmony, has lost harmony, and we strive to streamline everything, that is, every chaotic situation leads to harmony and stability. Again, if we resort to the image of a raging sea, for us the way out of this chaos would be to freeze the sea so that it becomes stationary – but this is not how God works in such situations.

The chaos that the Bible begins with is something else. These are all potentialities, all possible realities that have not yet taken shape. You can talk in such terms about the mind, about the feelings, about the mind and heart of the child. We can say that they are still in a chaotic state, in the sense that they are all there, all possibilities are given, but nothing has yet been revealed. They are like a kidney, which contains all the beauty of a flower, but still has to open, and if it does not open, then nothing will be revealed.

The primordial chaos of which the Bible speaks, it seems to me, is the limitless, unimaginable fullness of possibilities in which everything is contained—not only what could have been then, but what can be now and in the future. It's like a kidney that can open up, develop forever. And what is described in the Bible as the creation of the world is the act by which God calls one opportunity after another, waits for it to mature, become ready for birth, and then gives it shape, form, and lets it into life and reality. I think these images are important because the world we live in is still in this chaos, this creative chaos. This creative chaos has not yet manifested itself in all its possibilities, it continues to give rise to new realities, and each such reality, because of its novelty, is terrible to the old world.

There is a problem of mutual understanding between generations, there is a problem of how to understand the world in a certain era, if you were born and raised in another era. We may be amazed by what we see twenty or thirty years after we have reached maturity. Perhaps we will find ourselves facing a world that should be understandable and close, because it is inhabited by our descendants, our friends, and yet has become almost incomprehensible to us. In this case, again, we seek to “order” the world. This is what all dictators have done: they have found the world in becoming, or a world that has slid into disorder, and shaped it, but man-made, to the measure of man. Chaos scares us, we fear the unknown, we are afraid to look into the dark abyss because we do not know what will emerge from it and how we will cope with it. What happens to us if something or someone or a situation arises that we do not understand at all?

That, I think, is the situation we find ourselves in all the time, generation after generation, and even within our own lives. There are times when we fear what happens to us, what we become. I’m not talking about the basic level of being horrified when you realize that you’re being destroyed by drinking, by drugs, by the way you live, or by external conditions. I’m talking about what rises in us, and we discover something in ourselves that we never suspected. Again, it seems to us that the easiest way to suppress, to try to destroy what rises and frightens us. We are afraid of creative chaos, we are afraid of gradually emerging opportunities and we try to get out of the situation, turning back, betraying the new earth, bringing everything into a frozen balance.

Creative people can easily find a way out by projecting what happens in them, into a picture, into a sculpture, or into a piece of music, or into a play on stage. These people are in an advantageous position because the artist, provided he is a real artist, expresses more through himself than he even realizes. He will find that he has expressed on the canvas, in sound, in lines or colors, or forms, what he does not see in himself, it is a revelation to himself - on this basis, a psychologist can read a picture that the artist has created without understanding what he is creating.

I am not a painter, but I have had an experience that still amazes me, the key to which I received from an elderly woman. About thirty years ago a young man came to me with a huge canvas and said, “I was sent to you, saying that you could interpret this canvas for me.” I asked why. He replied, "I'm in psychoanalysis, my psychoanalyst can't understand this picture, I can't either." But we have a mutual friend (the same woman) who said, "You know, you're completely crazy, you need to go to someone like you," and sent me to you. I found it very flattering, so I looked at his painting and saw nothing. So I asked him to leave it with me and I stayed with him for three or four days. And then I started seeing something. Afterwards, I visited him once a month, examined his works, and interpreted them to him, until he could easily read his paintings, as he could read his poems or any of his works with understanding.

This can happen to everyone at some point in their lives – sometimes it’s easier to understand a person than they understand themselves. We must be able to face modern life in the same way. God is not afraid of chaos, God is at its core, evoking out of chaos all reality, a reality that will unfold with novelty, that is, frightening for us until everything reaches its fullness.

When I said that I believe that God is the Lord of harmony, but also the Lord of storms, I meant something even greater. The world around us is not that primordial chaos fraught with possibilities that have not yet been revealed, are not yet evil in themselves, are not yet spoiled, so to speak. We live in a world where what has been called into being has been horribly distorted. We live in a world of death, suffering, evil, incompleteness, and both sides of chaos are present in this world: the primary source of opportunity, potentiality, and distorted reality. And our task is more difficult, because we cannot simply contemplate, look at what arises from nothingness, or gradually grows into greater and greater perfection, like a child in the womb of a mother, like an embryo must develop into the fullness of a being (man or animal). We have to deal with destruction, with evil, with distortion, and here we have to play a decisive role.

One of the problems I see — maybe more clearly now than when I was younger (perhaps as you age you feel that the past is more harmonious and reliable than the present) — is that the challenge is not accepted, most people would like someone else to take the challenge. The believer, whenever there is a challenge or danger or tragedy, turns to God and says, “Protect me, I am in trouble.” A member of society appeals to the power-holder and says: "You must ensure my welfare!" Someone turns to philosophy, someone speaks with single actions. But it seems to me that we do not realize that each of us is called upon to take a responsible, thoughtful part in solving the problems before us. Whatever our philosophical convictions, we are sent into the world, placed in this world, and whenever we see its disharmony or ugliness, it is our business to look at these phenomena and ask ourselves the question: “What can be my contribution to making the world truly harmonious?” – not conventionally harmonious, not just decent, not just a world in which, in general, one can live. There are times when to get to a situation where you can live, you have to go through seemingly impossible moments, just as surgery may be necessary, or as a thunderstorm purifies the air.

It seems to me that the modern world presents us with a double challenge, and we should look at it rather than look away, which many of us would prefer not to see some aspects of life, because if we do not see, you are largely free from responsibility. The easiest thing to ignore is that people are starving, that they are persecuted, that people are suffering in prisons and dying in hospitals. It's self-deception, but we're all pretty much happy to be deceived or to be self-deceived, because it would be much more comfortable, much easier to live if you could forget about everything except what's good in my own life.

So much more courage is required of us than we would normally do: it is very important to face tragedies, to accept tragedy as a wound in the heart. And it is tempting to avoid the wound by turning pain into anger, because pain, when imposed on us, is accepted when we endure it, in a sense, a passive state. And anger is my own reaction: I can be harsh, I can be angry, I can act — not much, usually, and certainly it will not solve the problem, because, as the Epistle says, human anger does not create God’s righteousness (James 1:20). However, anger is easy, and it is very difficult to accept suffering. The highest expression of the latter I see, for example, in the way Christ accepts His suffering and His crucifixion: as a gift of Himself.

And secondly, it is not enough to meet events, to see the essence of things, to accept suffering. We are sent into this world to change it. And when I say change, I think of the many ways in which the world can be changed, least of all political or social restructuring. The first thing that has to happen is a change in ourselves that allows us to be in harmony, a harmony that can be transferred, spread around us.

This, I think, is more important than any change you can try to make around you in a different way. When Christ says that the kingdom of God is within us (Luke 17:21), it means that if God does not reign in our lives, if we do not have the mind of God, the heart of God, the will of God, the eye of God, everything we try to do or create will be disharmonious and incomplete to some extent. I’m not saying that each of us is capable of achieving all of this in its entirety, but to the extent that we have achieved it, it spreads around us in harmony, beauty, peace, love and changes everything around us. The act of love, the act of sacrificial love, changes something for everyone, even for those people who do not know about it, do not immediately notice it.

So we have to ask ourselves how brave we are to face things, and courage always means being willing to forget ourselves and look first at the situation and second at the need of the other. As long as we are focused on ourselves, our courage will be broken, because we will be afraid for our body, for our mind, for our emotions, and we will never be able to risk everything, even life and death. We must ask ourselves this question constantly, because we are timid, cowardly, we doubt. We are asked a question, and we skirt it and give an evasive answer, because it is easier than giving a direct answer. We have to do something and think: I’ll do this, the rest later, etc. And we need to educate ourselves to become those people who are sent to bring harmony, beauty, truth, love into the world.

Moffat’s New Testament translation says, “We are the vanguard of the kingdom of heaven.”177 We are those who must have an understanding of the divine perspective, who are set up to expand, deepen the vision of others, to bring light into it. We are not called to be a society of people who enjoy mutual communication, who rejoice when they hear wonderful words from each other, and look forward to the next opportunity to be together. We must be those whom God will take into His hand, sow so that the wind will blow us away, and somewhere we will fall into the ground. And there we have to put down roots and sprout, albeit at some cost. Our vocation is to participate with others in the construction of the city, the city of man, yes, but so that this city can correspond to the City of God. Or, in other words, we must build a city of man of such capacity, such depth, such holiness, that one of its citizens may be Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who became the Son of man. Everything that is not in this measure, everything that is less than this, is not a city of man worthy of man - I do not say worthy of God - it is too small for us. But to do so, we must face the challenge, face it, first face ourselves, reach the required level of peace and harmony, and act within that harmony—or shine around us, because we are called to be the light of the world.

Answers to questions

Don’t you think our world is in such a state that it’s too late to think about changing it?

No, I don't think it's too late. First, to say that it is too late is to condemn oneself to inaction, to retreat and only to add stagnation, to rot. And secondly, the world is amazingly young. I'm not talking about chimpanzees and dinosaurs, but if you're talking about the human species, we're very young, we're really new, recent settlers. We've done a lot of damage, but overall we're very young.

Besides, as far as I can tell, I am not a historian, but from what little I know, it is clear that the world is constantly going through ups and downs, through crises, through dark periods and light periods. And people in this generation, for the most part, feel that when things have gone into chaos, that must be it. Now, experience shows, or should show us, that there is an uplift every time, so I believe there is still time. Of course, I am not a prophet in this sense, but I think as long as I live I will act. When I die, the responsibility is no longer mine. But I’m not going to sit in a chair and say, “I don’t understand the world today.” I will continue to say what I think is true, I will try to share what I think is beautiful, and what comes out of it is none of my business.

But will it ever end? Or don't you believe that?

I believe there will come a point where everything will collapse dramatically, but I think we haven't reached that point yet. I remember that during the revolution in Russia, when there was still debate and dissent, someone asked a Christian preacher, a Baptist178, if he considered Lenin the Antichrist, and he replied: “No, he is too petty for that.” And when I look around, I think that all those who are sometimes called the embodiment of evil, too small, this image does not apply to them. I don't think we're ready for the ultimate tragedy. But in this sense, I am optimistic, because I am not afraid of the latest tragedy.

But have factors such as nuclear weapons not changed the whole situation in the world?

The presence of the atomic bomb, nuclear weapons, and so on, of course, introduced a different dimension, a dimension that had never been quantified before. Bad will or chance cannot be ruled out. But I don't remember who said that the decisive factor is not that there are nuclear weapons, the decisive factor is whether there is a person or a group of people willing to use such weapons. I think that’s the main thing I feel about it. Peace, security, etc., must begin with ourselves, in our midst. It is possible to destroy all nuclear weapons and yet wage a devastating war and completely destroy each other. Without nuclear weapons, life on earth can be destroyed. You can cause a famine that will take millions of people, you can kill with so-called conventional weapons until and on such a scale that our planet becomes depopulated. So the problem is with us, not the guns themselves. St. John Cassian, speaking of good and evil, said that very few things are good or evil, but most of them are neutral. Take, for example, a knife. It is neutral in itself, the problem is who has it and what they will do. Just like this. It’s all about us as people treating the world in which we live with reverence, treating each other with respect. It’s not about destructive means – it all depends on fear, hatred, greed, quality in us.

Nuclear weapons can hardly be considered as neutral as a knife. Shouldn't we fight this danger with all our might, to fight for peace?

What we say about nuclear energy has probably been experienced and expressed in other eras for other reasons. When gunpowder was invented, it frightened people as much as nuclear power scares us today. You know, I may be very insensitive, but when I was fifteen, I read the Stoics with great enthusiasm, and I remember reading a passage from Epictetus where he says there are two kinds of things: those with which something can be done, and those with which nothing can be done. Where you can do something, forget about the rest. Maybe I’m like an ostrich burying its head in the sand, but I just live day after day without even remembering that the world could be destroyed by nuclear power, or that I could be run over by a car, or that a burglar could climb into a temple. For me, the state of people who will do one way or another is important. That's what we can do, what we can do about it: help people realize that compassion, love is important.

In the movement for peace, in the struggle for peace, I am confused by the fact that this movement is largely justified by the argument: “You see how dangerous we are!” It doesn't matter that it's dangerous, it's scary, it's important that there's no love. We must become peacemakers not out of cowardice; our attitude towards our neighbour must change. And if that’s the case, it shouldn’t start with banning nuclear power plants, it should start with ourselves, with us, anywhere. I remember at the beginning of the war there was a raid on Paris and I went down to the shelter. There was a woman there who spoke with great fervor about the horrors of war and said, "It is unimaginable that in our time there are monsters like Hitler!" People who do not love their neighbor! If I had it in my hands, I would have stuck it with needles to death. It seems to me that this mood is very common today: if it were possible to destroy all the villains! But the moment you destroy the villain, you commit an equally destructive act, because what counts is not the quantity, but the quality of what you have done.

A French writer in the novel 179 has a story about a man who visited islands in the Pacific Ocean and there learned to call to life everything that is still able to live, but withered, faded. He returns to France, buys a piece of bare rocky ground and sings a love song to her. And the land begins to give life, to sprout with beauty, plants, and animals from all around come to live there in a community of friendship. Only one beast does not come, the fox. And this man, Monsieur Cyprien, is heartbroken: the poor fox does not understand how happy she will be in this recreated paradise, and he calls the fox, calls, calls - but the fox does not come! Moreover, from time to time, the fox drags the chicken of paradise and eats it. The compassion of Monsieur Cyprien is changing with impatience. And then the thought comes to him: if there was no fox, heaven would include everyone - and he kills the fox. He returns to his paradise: all the plants withered, all the animals fled.

I think here's a lesson for us in this respect, it happens to us, in us. I do not mean to say that I am completely insensitive to what may happen in a catastrophe, nuclear or any other, but this is not the worst evil, the worst evil, in the heart of man.

If we consider everything that can produce good or evil results neutral, then is fear our subjective reaction? And then, where is our faith?

I am not so naive as to think that fear is merely a subjective state and is caused by a lack of faith. Yes, anything that can be destructive, that threatens to destroy a person, his body, destroy the world in which we live, including ourselves, or destroy people morally, carries fear. But I think in history, we've seen things that are threatening and fearful, and we've learned to tame those things, starting with fire, flooding, lightning. A number of diseases, such as plague, smallpox and tuberculosis, have been eradicated in recent decades. When I was a medical student, there were whole departments of dying people from tuberculosis, now it is generally considered a mild disease, it is curable. And our role, I think, is to be tamers. We will have to deal with terrifying phenomena, man-made or natural, and our challenge is to learn how to meet them, deal with them, curb them, and ultimately use them. Even smallpox is used for vaccinations. Fire is used extremely widely, and also water, these elements are subdued. There are times when humanity carelessly forgets its role as a tamer, and then tragedies occur. But even if we leave aside man-made, man-made horrors, we need to tame much more.

Of course, the thing like nuclear energy is more frightening, I would say, not because it's lethal, it's simple: the end and that's it, but because of the side effects. So humanity needs to be very clear about its responsibility, and I think it's a challenge that humanity needs to face, because it's a moral challenge that you can't solve simply by giving up nuclear energy. Nowadays, the sense of responsibility in general is very poorly developed. In this case, we are faced with a direct question: “Are you aware of your responsibility?” Are you ready to take over? Or are you ready to destroy your own people and other peoples? And I think that if we take this as a challenge, we should take it very seriously, just as many centuries ago people had to deal with the attitude to fire, when they did not know how to make fire, but knew that fire could burn their homes and destroy everything around them; the same was true of water, etc.

Then how can we, imitating Peter, "get out of the boat"? How should this be expressed in practice?

You know, it's hard for me to answer that, because I don't think I've ever gotten off a boat myself! But it seems to me that we should be ready to break away from everything that seems to represent security, security, protection, and face the complexity and sometimes the horror of life. This does not mean climbing, but we should not take shelter, throw ourselves into a boat, seek refuge in a sacred place, etc., but rather be ready to stand up and face events.

Second, the moment we lose our former security, we will inevitably experience a sense of upliftment for a while, if only because we feel like heroes. You know, what you don't do out of virtue, you make out of vanity. But vanity won't get you far. At some point, you will feel that there is no solid ground under your feet, then you can act with determination. You can say: I have made a choice, and, no matter how scared I am, I will not give up. This happens, say, in war: you volunteer for a task and find yourself in the dark, in the cold and hunger, wet to the thread, around in danger, and so you want to be in shelter. And you can either run away or say: I made a decision and will stick to it. Maybe you'll lose heart, fail, and there's nothing dishonest about it - none of us are patented heroes. But it happens because you suddenly remember what might happen to you, instead of thinking about the meaning of your actions or where you are going. It may support the idea of how important the ultimate goal is, and that you, your life, your physical integrity, or your happiness are very small compared to the goal itself.

Let me give you an example. I once taught at the Russian Gymnasium in Paris, and in one of the junior classes there was a girl who went to live with her relatives in Yugoslavia during the war. There was nothing special about her - an ordinary girl, a sweet, kind, whole nature. During the bombing of Belgrade, the house where she lived was destroyed. All the tenants ran out, but when they began to look around, they saw that one sick old woman could not come out. And the girl did not hesitate, she entered the fire - and remained there. But the impulse, the idea that this old woman should not perish, that she should not burn alive, was stronger than the instinctive movement to save herself. Between right and courageous thought and action, she did not allow a brief moment, which allows all of us to say: “Should I?” There should be no gap between thought and action.

In the story of Peter there is another inspiring moment. He begins to sink, notices his insecurity, his fear, his lack of faith, realizes that he remembers more of himself than he remembers of Christ—the Christ whom he loves and from whom he will nevertheless later renounce, although he truly loves Him—and cries out, “I perish, save!” and finds himself on the shore. And I think it's impossible to just say, "I'm going to get out of the boat, walk on the waves, reach the hurricane core and escape!" We must be prepared to step out into the sea, which is full of dangers, and if we think of the human sea, we will find ourselves surrounded by dangers of all kinds, large or small. At some point, you might say, “I don’t have the strength anymore, I need some kind of support or help!” So look for help and support, because if you decide, “No, I’ll be heroic to the end,” you can break. So you have to have the humility to say, "No, this is - alas! - all that I am capable of." And at that moment, salvation will come in response to your humility.

© Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh Foundation

Published in the book Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. Labor. Tom 2. Moscow, Publishing House Practice

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.pravmir.ru/v-mire-haosa-smerti-stradaniya-zla-nepolnotyi/

Every generation faces change. For some, change means a certain degree of bewilderment: what was previously self-evident, what seemed reliable, gradually disintegrates or is called into question, often in a very radical way, violently. For others, change is a different kind of uncertainty: young people enter a changing world and do not know where it will lead them. Thus, both groups – those who think that the old world is collapsing, disappearing, changing beyond recognition, and those who find themselves in a world that is itself becoming, the shape of which they cannot understand, can not see – face the same challenge, but in different ways. And I'd like to present you two or three images and my own conclusions, because the only thing you can do about your life is to share what you've learned or what you think is true.

All of us, as a rule, expect that everything in life should be safe, harmonious, peaceful, without problems, that life should develop like a well-groomed plant grows from a seed: a small sprout under cover gradually reaches its full bloom. But we know from experience that this is not the case. It seems to me that God is the God of tempest, just as He is the God of harmony and peace. And the first image that comes to mind is the Gospel story of Christ walking on the sea in the midst of a storm and Peter trying to come to Him in the waves (Matthew 14:22-34).

Let us leave aside the historical aspect of the story. What happened here, what does that tell us? Christ did not calm the storm by the mere fact of His presence. And this seems important to me, because all too often, when we are caught by a storm, whether it is small or great, we tend to think that a storm has broken out, so God is not here, so something is wrong (usually with God, less often with us). And secondly, since Christ can be in the middle of a storm and not be hesitant, broken, destroyed, it means that He is in equilibrium. And in a hurricane, in a tornado, in any storm, the point of stability, the point where all the raging forces of the elements collide, balancing themselves, is at the very heart of the hurricane; and here God is. Not at the edge, not where He could safely go out on land while we are drowning in the sea, He is where the situation is worst, where the raging, the most confrontation.

If we recall the story of Peter walking on water, we see that his impulse was correct. Peter saw that he was in mortal danger. The small boat in which he is, can sink, it can break the waves, turn the raging wind. And in the midst of the storm, he saw the Lord in His marvelous peace, and he realized that if he could reach that point himself, he too would be at the heart of the storm—and yet in untold peace. And he was ready to leave the safety of the boat, which represented protection from the storm, albeit fragile, but still protection (other disciples were saved in it), and go out into the storm. He could not reach the Lord because he remembered that he might drown. He began to think about himself, about the storm, about the fact that he had never yet walked on the waves, he turned to himself and could no longer rush to God. He lost the safety of the boat and did not find the complete safety of the place where the Lord was.

And it seems to me that when we think of ourselves in the modern world (and, as I said, the world is modern from generation to generation, there is no time when the world is not the same storm, only to each generation it is presented in a different guise), we all face the same problem: the small boat provides some protection, everything is fraught with danger, in the center of the storm is the Lord, and the question arises: Am I ready to go to Him? This is the first image, and I let everyone respond to it on their own.

The second image that comes to mind is the act of creation. The first line of the Bible says that God created heaven and earth (Genesis 1:1). When I think about it, this is what I think. God, the fullness of everything, harmony, beauty, summons by name all possible creatures. He calls, and every creature rises from nothingness, from complete, radical absence, rises in primordial harmony and beauty, and the first thing she sees is the complete, perfect beauty of God, the first thing she perceives is complete harmony in the Lord. And the name of this harmony is love, dynamic, creative love. This is what we express when we say that the perfect image of the relationship of love is found in the Trinity.

But if we think about the next lines, or rather the second half of the sentence, we see something that should make us think about our situation. It says that the first call of God created what in Hebrew is called chaos, chaos, chaos, out of which God causes objects, forms, realities. The Bible uses different words when referring to the primary act of creating this chaos (what it is, I will try to define it now) and when referring to further creation. In the first case, a word is used that speaks of creation out of nothing that was not, in the second, of the creation of something out of, so to speak, already existing material.

Chaos is always thought of as disorder, disorganized being. We think of the chaos in our room, implying that the room has to be cleaned and we've turned it all over. When we think of chaos on the larger scale of life, in the world, we think of a city that has been bombarded, or a society where competing interests clash, where love has faded or disappeared, where nothing is left but greed, egocentrism, fear, hatred, etc. We understand chaos as a situation where what should be harmonious, has lost harmony, has lost harmony, and we strive to streamline everything, that is, every chaotic situation leads to harmony and stability. Again, if we resort to the image of a raging sea, for us the way out of this chaos would be to freeze the sea so that it becomes stationary – but this is not how God works in such situations.

The chaos that the Bible begins with is something else. These are all potentialities, all possible realities that have not yet taken shape. You can talk in such terms about the mind, about the feelings, about the mind and heart of the child. We can say that they are still in a chaotic state, in the sense that they are all there, all possibilities are given, but nothing has yet been revealed. They are like a kidney, which contains all the beauty of a flower, but still has to open, and if it does not open, then nothing will be revealed.

The primordial chaos of which the Bible speaks, it seems to me, is the limitless, unimaginable fullness of possibilities in which everything is contained—not only what could have been then, but what can be now and in the future. It's like a kidney that can open up, develop forever. And what is described in the Bible as the creation of the world is the act by which God calls one opportunity after another, waits for it to mature, become ready for birth, and then gives it shape, form, and lets it into life and reality. I think these images are important because the world we live in is still in this chaos, this creative chaos. This creative chaos has not yet manifested itself in all its possibilities, it continues to give rise to new realities, and each such reality, because of its novelty, is terrible to the old world.

There is a problem of mutual understanding between generations, there is a problem of how to understand the world in a certain era, if you were born and raised in another era. We may be amazed by what we see twenty or thirty years after we have reached maturity. Perhaps we will find ourselves facing a world that should be understandable and close, because it is inhabited by our descendants, our friends, and yet has become almost incomprehensible to us. In this case, again, we seek to “order” the world. This is what all dictators have done: they have found the world in becoming, or a world that has slid into disorder, and shaped it, but man-made, to the measure of man. Chaos scares us, we fear the unknown, we are afraid to look into the dark abyss because we do not know what will emerge from it and how we will cope with it. What happens to us if something or someone or a situation arises that we do not understand at all?

That, I think, is the situation we find ourselves in all the time, generation after generation, and even within our own lives. There are times when we fear what happens to us, what we become. I’m not talking about the basic level of being horrified when you realize that you’re being destroyed by drinking, by drugs, by the way you live, or by external conditions. I’m talking about what rises in us, and we discover something in ourselves that we never suspected. Again, it seems to us that the easiest way to suppress, to try to destroy what rises and frightens us. We are afraid of creative chaos, we are afraid of gradually emerging opportunities and we try to get out of the situation, turning back, betraying the new earth, bringing everything into a frozen balance.

Creative people can easily find a way out by projecting what happens in them, into a picture, into a sculpture, or into a piece of music, or into a play on stage. These people are in an advantageous position because the artist, provided he is a real artist, expresses more through himself than he even realizes. He will find that he has expressed on the canvas, in sound, in lines or colors, or forms, what he does not see in himself, it is a revelation to himself - on this basis, a psychologist can read a picture that the artist has created without understanding what he is creating.

I am not a painter, but I have had an experience that still amazes me, the key to which I received from an elderly woman. About thirty years ago a young man came to me with a huge canvas and said, “I was sent to you, saying that you could interpret this canvas for me.” I asked why. He replied, "I'm in psychoanalysis, my psychoanalyst can't understand this picture, I can't either." But we have a mutual friend (the same woman) who said, "You know, you're completely crazy, you need to go to someone like you," and sent me to you. I found it very flattering, so I looked at his painting and saw nothing. So I asked him to leave it with me and I stayed with him for three or four days. And then I started seeing something. Afterwards, I visited him once a month, examined his works, and interpreted them to him, until he could easily read his paintings, as he could read his poems or any of his works with understanding.

This can happen to everyone at some point in their lives – sometimes it’s easier to understand a person than they understand themselves. We must be able to face modern life in the same way. God is not afraid of chaos, God is at its core, evoking out of chaos all reality, a reality that will unfold with novelty, that is, frightening for us until everything reaches its fullness.

When I said that I believe that God is the Lord of harmony, but also the Lord of storms, I meant something even greater. The world around us is not that primordial chaos fraught with possibilities that have not yet been revealed, are not yet evil in themselves, are not yet spoiled, so to speak. We live in a world where what has been called into being has been horribly distorted. We live in a world of death, suffering, evil, incompleteness, and both sides of chaos are present in this world: the primary source of opportunity, potentiality, and distorted reality. And our task is more difficult, because we cannot simply contemplate, look at what arises from nothingness, or gradually grows into greater and greater perfection, like a child in the womb of a mother, like an embryo must develop into the fullness of a being (man or animal). We have to deal with destruction, with evil, with distortion, and here we have to play a decisive role.

One of the problems I see — maybe more clearly now than when I was younger (perhaps as you age you feel that the past is more harmonious and reliable than the present) — is that the challenge is not accepted, most people would like someone else to take the challenge. The believer, whenever there is a challenge or danger or tragedy, turns to God and says, “Protect me, I am in trouble.” A member of society appeals to the power-holder and says: "You must ensure my welfare!" Someone turns to philosophy, someone speaks with single actions. But it seems to me that we do not realize that each of us is called upon to take a responsible, thoughtful part in solving the problems before us. Whatever our philosophical convictions, we are sent into the world, placed in this world, and whenever we see its disharmony or ugliness, it is our business to look at these phenomena and ask ourselves the question: “What can be my contribution to making the world truly harmonious?” – not conventionally harmonious, not just decent, not just a world in which, in general, one can live. There are times when to get to a situation where you can live, you have to go through seemingly impossible moments, just as surgery may be necessary, or as a thunderstorm purifies the air.

It seems to me that the modern world presents us with a double challenge, and we should look at it rather than look away, which many of us would prefer not to see some aspects of life, because if we do not see, you are largely free from responsibility. The easiest thing to ignore is that people are starving, that they are persecuted, that people are suffering in prisons and dying in hospitals. It's self-deception, but we're all pretty much happy to be deceived or to be self-deceived, because it would be much more comfortable, much easier to live if you could forget about everything except what's good in my own life.

So much more courage is required of us than we would normally do: it is very important to face tragedies, to accept tragedy as a wound in the heart. And it is tempting to avoid the wound by turning pain into anger, because pain, when imposed on us, is accepted when we endure it, in a sense, a passive state. And anger is my own reaction: I can be harsh, I can be angry, I can act — not much, usually, and certainly it will not solve the problem, because, as the Epistle says, human anger does not create God’s righteousness (James 1:20). However, anger is easy, and it is very difficult to accept suffering. The highest expression of the latter I see, for example, in the way Christ accepts His suffering and His crucifixion: as a gift of Himself.

And secondly, it is not enough to meet events, to see the essence of things, to accept suffering. We are sent into this world to change it. And when I say change, I think of the many ways in which the world can be changed, least of all political or social restructuring. The first thing that has to happen is a change in ourselves that allows us to be in harmony, a harmony that can be transferred, spread around us.

This, I think, is more important than any change you can try to make around you in a different way. When Christ says that the kingdom of God is within us (Luke 17:21), it means that if God does not reign in our lives, if we do not have the mind of God, the heart of God, the will of God, the eye of God, everything we try to do or create will be disharmonious and incomplete to some extent. I’m not saying that each of us is capable of achieving all of this in its entirety, but to the extent that we have achieved it, it spreads around us in harmony, beauty, peace, love and changes everything around us. The act of love, the act of sacrificial love, changes something for everyone, even for those people who do not know about it, do not immediately notice it.

So we have to ask ourselves how brave we are to face things, and courage always means being willing to forget ourselves and look first at the situation and second at the need of the other. As long as we are focused on ourselves, our courage will be broken, because we will be afraid for our body, for our mind, for our emotions, and we will never be able to risk everything, even life and death. We must ask ourselves this question constantly, because we are timid, cowardly, we doubt. We are asked a question, and we skirt it and give an evasive answer, because it is easier than giving a direct answer. We have to do something and think: I’ll do this, the rest later, etc. And we need to educate ourselves to become those people who are sent to bring harmony, beauty, truth, love into the world.

Moffat’s New Testament translation says, “We are the vanguard of the kingdom of heaven.”177 We are those who must have an understanding of the divine perspective, who are set up to expand, deepen the vision of others, to bring light into it. We are not called to be a society of people who enjoy mutual communication, who rejoice when they hear wonderful words from each other, and look forward to the next opportunity to be together. We must be those whom God will take into His hand, sow so that the wind will blow us away, and somewhere we will fall into the ground. And there we have to put down roots and sprout, albeit at some cost. Our vocation is to participate with others in the construction of the city, the city of man, yes, but so that this city can correspond to the City of God. Or, in other words, we must build a city of man of such capacity, such depth, such holiness, that one of its citizens may be Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who became the Son of man. Everything that is not in this measure, everything that is less than this, is not a city of man worthy of man - I do not say worthy of God - it is too small for us. But to do so, we must face the challenge, face it, first face ourselves, reach the required level of peace and harmony, and act within that harmony—or shine around us, because we are called to be the light of the world.

Answers to questions

Don’t you think our world is in such a state that it’s too late to think about changing it?

No, I don't think it's too late. First, to say that it is too late is to condemn oneself to inaction, to retreat and only to add stagnation, to rot. And secondly, the world is amazingly young. I'm not talking about chimpanzees and dinosaurs, but if you're talking about the human species, we're very young, we're really new, recent settlers. We've done a lot of damage, but overall we're very young.

Besides, as far as I can tell, I am not a historian, but from what little I know, it is clear that the world is constantly going through ups and downs, through crises, through dark periods and light periods. And people in this generation, for the most part, feel that when things have gone into chaos, that must be it. Now, experience shows, or should show us, that there is an uplift every time, so I believe there is still time. Of course, I am not a prophet in this sense, but I think as long as I live I will act. When I die, the responsibility is no longer mine. But I’m not going to sit in a chair and say, “I don’t understand the world today.” I will continue to say what I think is true, I will try to share what I think is beautiful, and what comes out of it is none of my business.

But will it ever end? Or don't you believe that?

I believe there will come a point where everything will collapse dramatically, but I think we haven't reached that point yet. I remember that during the revolution in Russia, when there was still debate and dissent, someone asked a Christian preacher, a Baptist178, if he considered Lenin the Antichrist, and he replied: “No, he is too petty for that.” And when I look around, I think that all those who are sometimes called the embodiment of evil, too small, this image does not apply to them. I don't think we're ready for the ultimate tragedy. But in this sense, I am optimistic, because I am not afraid of the latest tragedy.

But have factors such as nuclear weapons not changed the whole situation in the world?

The presence of the atomic bomb, nuclear weapons, and so on, of course, introduced a different dimension, a dimension that had never been quantified before. Bad will or chance cannot be ruled out. But I don't remember who said that the decisive factor is not that there are nuclear weapons, the decisive factor is whether there is a person or a group of people willing to use such weapons. I think that’s the main thing I feel about it. Peace, security, etc., must begin with ourselves, in our midst. It is possible to destroy all nuclear weapons and yet wage a devastating war and completely destroy each other. Without nuclear weapons, life on earth can be destroyed. You can cause a famine that will take millions of people, you can kill with so-called conventional weapons until and on such a scale that our planet becomes depopulated. So the problem is with us, not the guns themselves. St. John Cassian, speaking of good and evil, said that very few things are good or evil, but most of them are neutral. Take, for example, a knife. It is neutral in itself, the problem is who has it and what they will do. Just like this. It’s all about us as people treating the world in which we live with reverence, treating each other with respect. It’s not about destructive means – it all depends on fear, hatred, greed, quality in us.

Nuclear weapons can hardly be considered as neutral as a knife. Shouldn't we fight this danger with all our might, to fight for peace?

What we say about nuclear energy has probably been experienced and expressed in other eras for other reasons. When gunpowder was invented, it frightened people as much as nuclear power scares us today. You know, I may be very insensitive, but when I was fifteen, I read the Stoics with great enthusiasm, and I remember reading a passage from Epictetus where he says there are two kinds of things: those with which something can be done, and those with which nothing can be done. Where you can do something, forget about the rest. Maybe I’m like an ostrich burying its head in the sand, but I just live day after day without even remembering that the world could be destroyed by nuclear power, or that I could be run over by a car, or that a burglar could climb into a temple. For me, the state of people who will do one way or another is important. That's what we can do, what we can do about it: help people realize that compassion, love is important.

In the movement for peace, in the struggle for peace, I am confused by the fact that this movement is largely justified by the argument: “You see how dangerous we are!” It doesn't matter that it's dangerous, it's scary, it's important that there's no love. We must become peacemakers not out of cowardice; our attitude towards our neighbour must change. And if that’s the case, it shouldn’t start with banning nuclear power plants, it should start with ourselves, with us, anywhere. I remember at the beginning of the war there was a raid on Paris and I went down to the shelter. There was a woman there who spoke with great fervor about the horrors of war and said, "It is unimaginable that in our time there are monsters like Hitler!" People who do not love their neighbor! If I had it in my hands, I would have stuck it with needles to death. It seems to me that this mood is very common today: if it were possible to destroy all the villains! But the moment you destroy the villain, you commit an equally destructive act, because what counts is not the quantity, but the quality of what you have done.

A French writer in the novel 179 has a story about a man who visited islands in the Pacific Ocean and there learned to call to life everything that is still able to live, but withered, faded. He returns to France, buys a piece of bare rocky ground and sings a love song to her. And the land begins to give life, to sprout with beauty, plants, and animals from all around come to live there in a community of friendship. Only one beast does not come, the fox. And this man, Monsieur Cyprien, is heartbroken: the poor fox does not understand how happy she will be in this recreated paradise, and he calls the fox, calls, calls - but the fox does not come! Moreover, from time to time, the fox drags the chicken of paradise and eats it. The compassion of Monsieur Cyprien is changing with impatience. And then the thought comes to him: if there was no fox, heaven would include everyone - and he kills the fox. He returns to his paradise: all the plants withered, all the animals fled.

I think here's a lesson for us in this respect, it happens to us, in us. I do not mean to say that I am completely insensitive to what may happen in a catastrophe, nuclear or any other, but this is not the worst evil, the worst evil, in the heart of man.

If we consider everything that can produce good or evil results neutral, then is fear our subjective reaction? And then, where is our faith?

I am not so naive as to think that fear is merely a subjective state and is caused by a lack of faith. Yes, anything that can be destructive, that threatens to destroy a person, his body, destroy the world in which we live, including ourselves, or destroy people morally, carries fear. But I think in history, we've seen things that are threatening and fearful, and we've learned to tame those things, starting with fire, flooding, lightning. A number of diseases, such as plague, smallpox and tuberculosis, have been eradicated in recent decades. When I was a medical student, there were whole departments of dying people from tuberculosis, now it is generally considered a mild disease, it is curable. And our role, I think, is to be tamers. We will have to deal with terrifying phenomena, man-made or natural, and our challenge is to learn how to meet them, deal with them, curb them, and ultimately use them. Even smallpox is used for vaccinations. Fire is used extremely widely, and also water, these elements are subdued. There are times when humanity carelessly forgets its role as a tamer, and then tragedies occur. But even if we leave aside man-made, man-made horrors, we need to tame much more.

Of course, the thing like nuclear energy is more frightening, I would say, not because it's lethal, it's simple: the end and that's it, but because of the side effects. So humanity needs to be very clear about its responsibility, and I think it's a challenge that humanity needs to face, because it's a moral challenge that you can't solve simply by giving up nuclear energy. Nowadays, the sense of responsibility in general is very poorly developed. In this case, we are faced with a direct question: “Are you aware of your responsibility?” Are you ready to take over? Or are you ready to destroy your own people and other peoples? And I think that if we take this as a challenge, we should take it very seriously, just as many centuries ago people had to deal with the attitude to fire, when they did not know how to make fire, but knew that fire could burn their homes and destroy everything around them; the same was true of water, etc.

Then how can we, imitating Peter, "get out of the boat"? How should this be expressed in practice?

You know, it's hard for me to answer that, because I don't think I've ever gotten off a boat myself! But it seems to me that we should be ready to break away from everything that seems to represent security, security, protection, and face the complexity and sometimes the horror of life. This does not mean climbing, but we should not take shelter, throw ourselves into a boat, seek refuge in a sacred place, etc., but rather be ready to stand up and face events.

Second, the moment we lose our former security, we will inevitably experience a sense of upliftment for a while, if only because we feel like heroes. You know, what you don't do out of virtue, you make out of vanity. But vanity won't get you far. At some point, you will feel that there is no solid ground under your feet, then you can act with determination. You can say: I have made a choice, and, no matter how scared I am, I will not give up. This happens, say, in war: you volunteer for a task and find yourself in the dark, in the cold and hunger, wet to the thread, around in danger, and so you want to be in shelter. And you can either run away or say: I made a decision and will stick to it. Maybe you'll lose heart, fail, and there's nothing dishonest about it - none of us are patented heroes. But it happens because you suddenly remember what might happen to you, instead of thinking about the meaning of your actions or where you are going. It may support the idea of how important the ultimate goal is, and that you, your life, your physical integrity, or your happiness are very small compared to the goal itself.

Let me give you an example. I once taught at the Russian Gymnasium in Paris, and in one of the junior classes there was a girl who went to live with her relatives in Yugoslavia during the war. There was nothing special about her - an ordinary girl, a sweet, kind, whole nature. During the bombing of Belgrade, the house where she lived was destroyed. All the tenants ran out, but when they began to look around, they saw that one sick old woman could not come out. And the girl did not hesitate, she entered the fire - and remained there. But the impulse, the idea that this old woman should not perish, that she should not burn alive, was stronger than the instinctive movement to save herself. Between right and courageous thought and action, she did not allow a brief moment, which allows all of us to say: “Should I?” There should be no gap between thought and action.

In the story of Peter there is another inspiring moment. He begins to sink, notices his insecurity, his fear, his lack of faith, realizes that he remembers more of himself than he remembers of Christ—the Christ whom he loves and from whom he will nevertheless later renounce, although he truly loves Him—and cries out, “I perish, save!” and finds himself on the shore. And I think it's impossible to just say, "I'm going to get out of the boat, walk on the waves, reach the hurricane core and escape!" We must be prepared to step out into the sea, which is full of dangers, and if we think of the human sea, we will find ourselves surrounded by dangers of all kinds, large or small. At some point, you might say, “I don’t have the strength anymore, I need some kind of support or help!” So look for help and support, because if you decide, “No, I’ll be heroic to the end,” you can break. So you have to have the humility to say, "No, this is - alas! - all that I am capable of." And at that moment, salvation will come in response to your humility.

© Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh Foundation

Published in the book Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. Labor. Tom 2. Moscow, Publishing House Practice

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.pravmir.ru/v-mire-haosa-smerti-stradaniya-zla-nepolnotyi/