581

Why are we so often do NOT UNDERSTAND each other

As alien languages, piraha Indians, Wittgenstein and poincaré lingvisticheskii of relativity help us to understand why we so often do not understand each other.

On the Ground arriving alien ships are shaped weird. They do not give any signals, and upon contact it turns out that this aliens is absolutely indistinguishable. To find out what purpose these guests arrived, the government hires linguists. Deciphering an alien language shows that their picture of the world, the non-linear time: past, present and future exist simultaneously, and the principles of freedom of choice and the causal connection just isn't there.

This is the conceptual background of the recent film "Arrival" (Arrival, 2016), based on the fantastic novel by Ted Chan, "the Story of your life". At the heart of this story is the hypothesis of linguistic relativity Sepira-Saxon, according to which language determines our ways of perceiving the world.

Frame from the movie "the Arrival" (2016)

The difference in behavior in this case, it is caused by nothing other than differences in the linguistic marking items. Linguist Benjamin Lee Wharf has not yet become a linguist and worked at an insurance company when he noticed that the different names of things influences human behavior.

If people are in the warehouse "gasoline tanks", they will behave cautiously, but if it's a warehouse "empty gasoline tanks", they are easy, you can smoke and even throw cigarette butts on the ground. Meanwhile, the "empty" tanks are not less dangerous than full: they are the remnants of gasoline and explosive evaporation (and the warehouse staff are aware of this).

"Strong variant" hypothesis Sepira-Saxon assumes that language determines thinking and cognitive processes. "Weaker version" argues that language influences thinking, but does not define it entirely. The first version of the hypothesis, the result of a long debate was rejected. At the extreme, it would imply that the contact between speakers of different languages is impossible. But "weaker version" of a hypothesis is good enough to explain many phenomena of our reality. It helps to understand why we so often do not understand each other.

The aliens in "the Arrival" communicate with visual ideographs, not sounds. Source: arstechnica.com

In 1977, Christian missionary Daniel Everett first arrived in the village of an Indian tribe, the piraha, located on the river Nor in the Amazon basin. He had to learn to do this almost unexplored language of the piraha and convert it to the Bible to convert the Indians to Christianity. Everett spent among the piraha for about 30 years. During this time he ceased to be a Christian and realized how narrow was his ideas about thinking and language:

I used to think that if you try, you can see the world through the eyes of others and thereby learn to respect each other's views. But, living among the piraha, I have realized that our expectations and cultural baggage and life experiences are sometimes so different that the picture common to all of reality becomes untranslatable into the language of another culture.

Daniel Everett from the book "don't sleep — circle of snakes."

In the culture of the piraha is not to say that is not included in the direct experience of participants in the communication. Every story should be a witness, otherwise it does not make much sense. Any abstract construction and generalization of Indians will be simply incomprehensible.

Therefore, the piraha have no cardinal numbers. There are words for "more" and "less", but their use is always tied to specific subjects. Number — this is a generalization, because nobody saw what "three" or "fifteen". This does not mean that the piraha can't count, because the presentation about the unit they have is still there. They see that fish in the boat was more or less, but the solution to arithmetic problems about the fish shop it would be completely absurd occupation.

For this reason, the piraha have no myths or stories about creation, the origin of man, animals or plants. The people of the tribe often tell each other stories, and some of them even are not devoid of narrative skill. But it can only be stories from their lives, something seen with my own eyes.

When Everett was sitting with one of the Indians, and told him about the Christian God, he asked him:

— What else does your God do?

Well, he created the stars and the earth, ' I said, and then asked himself:

— What do they say about the piraha people?

— Well, the piraha people say it's all nobody was created, he said.

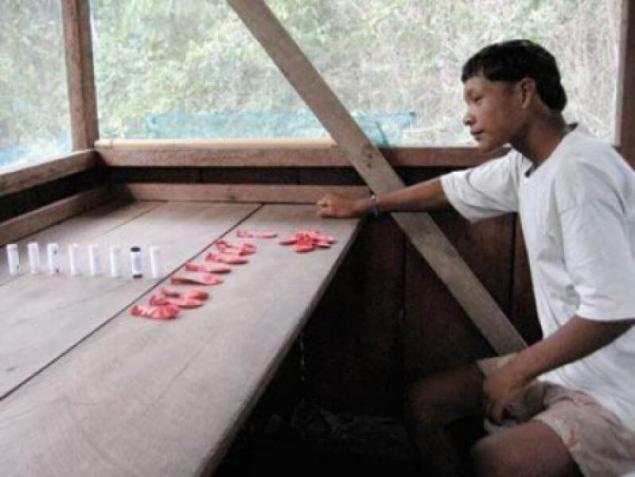

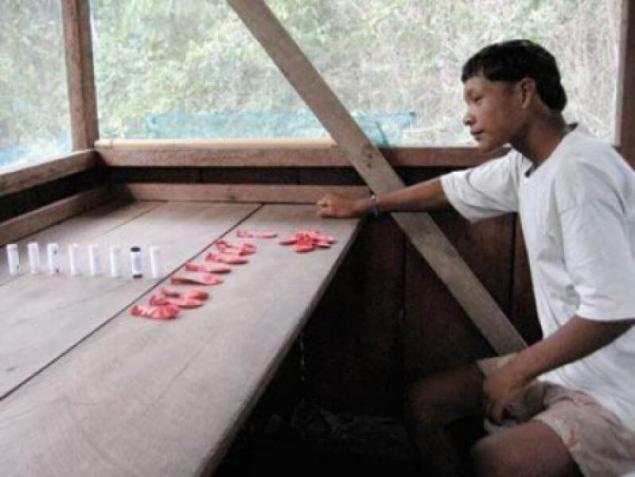

Daniel Everett with the piraha Indians. Source: hercampus.com

Because of the principle of direct perception of piraha failed to convert to Christianity. In our religions, tells about the events, witnesses who have long departed to another world, so to Express these stories in the language of piraha is simply impossible. At the beginning of his mission, Everett was convinced that the spiritual message he carries to the Indians, is absolutely universal. Permeated their language and way of perceiving the world, he realized that it is not so.

Even if we accurately translate the New Testament into the language of the piraha and make sure that every word for them is clear, this does not mean that our story will have meaning for them. While the piraha believe that can see the spirits that come to the village and talk to them. For them, these spirits are not less real than the Indians themselves. This is further evidence of the limitations of our common sense. What is ordinary for us has no meaning for others.

Everett argues that his findings refute the hypothesis of universal grammar of Noam Chomsky that all languages have a basic component — a certain deep structure, the possession of which is inherent in human biology. The fact that this hypothesis tells us nothing about the relationship of language, culture and thinking. It does not explain why we so often do not understand each other."For those of us who do not believe in spirits, it seems absurd that you can see them. But this is just our point of view". One of the basic components of any language, according to Chomsky, recursion is. It makes possible such statements as "bring me nails that brought Dan" or "friend's house hunter". Piraha can easily do without such structures. Instead, they use chains of simple sentences: "Bring me nails. Nails brought Dan." It turns out that recursion is present, but not at the level of grammar but at the level of cognitive processes. The most basic elements of thinking are expressed in different languages in different ways.

Photo of one of the experiments. Source: sciencedaily.com

In "Philosophical investigations" Ludwig Wittgenstein suggests: if a lion could talk we wouldn't understand him. Even if we learn the lion's language, it does not necessarily make his statements understandable to us. There is no universal language — a particular "form of life" with common ways to think, act and speak.

Even mathematics seems universal not because of its intrinsic properties, but only because we all teach the multiplication table. This observation is clearly confirmed by the experiments of Soviet psychologists conducted in the 30-ies of the last century under the leadership of Alexander Luria and Lev Vygotsky. Approval type "A is B B is C therefore A is C" does not have universal nature. Without schooling to anybody and in a head has not come, that about something to do, you can talk in this way.

Consider at first glance a simple and innocent statement: "the Cat is on the Mat". It would seem, understand this statement and test its validity easy: it is enough to look around and make sure the four-legged furry creature is the subject, which we call the Mat.

From this point of view does not mean that language determines thinking, as claimed by the "strong version of" linguistic relativity hypothesis. Language and behaviour jointly determine each other. If your friend says "fuck you to hell" after you gave him a little tip for you, that might mean "Thanks, buddy, I'll do that," but to outside observers, this form of gratitude will sound at least strange.

Now imagine (as it is offered by Oleg Kharkhordin and Vadim Volkov in the book "Theory of practices") that cats and mats are participating in some alien ritual distant to us culture. In this tribe arrives to the researcher, but the ritual isn't allowed because it is prohibited by the gods. Scientist conscientiously tries to understand the meaning of the ritual according to their informants. He said that the climax of the rite "the cat is on the Mat".

Gathering the necessary data, the researcher returns home. But he may not know that because of the difficulties of the rite shamans have long used the dried stuffed cats that can balance on the tail; carpets-mats roll into a tube and placed on end, and on top, placed a dead cat balanced on his tail. Still hold true the statement "the cat is on the Mat"? Yes, but its meaning has changed dramatically.

The art of communication: WHAT we say and HOW we understandGraham hill: Less stuff — more happiness

To understand aliens, the heroine of "Arrival" had to change their views over time. To understand the piraha, Daniel Everett had to give up the belief that his faith is universal. To understand each other, we need to be able to put their views on reality into question.

Talk to relatives, colleagues or neighbors, of course, is easier than semenovii aliens or the Amazonian Indians. But to make concessions to someone else's common sense to understand others and be understood, we still have to constantly.published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

Source: newtonew.com/overview/linguistics-of-misunderstanding

On the Ground arriving alien ships are shaped weird. They do not give any signals, and upon contact it turns out that this aliens is absolutely indistinguishable. To find out what purpose these guests arrived, the government hires linguists. Deciphering an alien language shows that their picture of the world, the non-linear time: past, present and future exist simultaneously, and the principles of freedom of choice and the causal connection just isn't there.

This is the conceptual background of the recent film "Arrival" (Arrival, 2016), based on the fantastic novel by Ted Chan, "the Story of your life". At the heart of this story is the hypothesis of linguistic relativity Sepira-Saxon, according to which language determines our ways of perceiving the world.

Frame from the movie "the Arrival" (2016)

The difference in behavior in this case, it is caused by nothing other than differences in the linguistic marking items. Linguist Benjamin Lee Wharf has not yet become a linguist and worked at an insurance company when he noticed that the different names of things influences human behavior.

If people are in the warehouse "gasoline tanks", they will behave cautiously, but if it's a warehouse "empty gasoline tanks", they are easy, you can smoke and even throw cigarette butts on the ground. Meanwhile, the "empty" tanks are not less dangerous than full: they are the remnants of gasoline and explosive evaporation (and the warehouse staff are aware of this).

"Strong variant" hypothesis Sepira-Saxon assumes that language determines thinking and cognitive processes. "Weaker version" argues that language influences thinking, but does not define it entirely. The first version of the hypothesis, the result of a long debate was rejected. At the extreme, it would imply that the contact between speakers of different languages is impossible. But "weaker version" of a hypothesis is good enough to explain many phenomena of our reality. It helps to understand why we so often do not understand each other.

The aliens in "the Arrival" communicate with visual ideographs, not sounds. Source: arstechnica.com

In 1977, Christian missionary Daniel Everett first arrived in the village of an Indian tribe, the piraha, located on the river Nor in the Amazon basin. He had to learn to do this almost unexplored language of the piraha and convert it to the Bible to convert the Indians to Christianity. Everett spent among the piraha for about 30 years. During this time he ceased to be a Christian and realized how narrow was his ideas about thinking and language:

I used to think that if you try, you can see the world through the eyes of others and thereby learn to respect each other's views. But, living among the piraha, I have realized that our expectations and cultural baggage and life experiences are sometimes so different that the picture common to all of reality becomes untranslatable into the language of another culture.

Daniel Everett from the book "don't sleep — circle of snakes."

In the culture of the piraha is not to say that is not included in the direct experience of participants in the communication. Every story should be a witness, otherwise it does not make much sense. Any abstract construction and generalization of Indians will be simply incomprehensible.

Therefore, the piraha have no cardinal numbers. There are words for "more" and "less", but their use is always tied to specific subjects. Number — this is a generalization, because nobody saw what "three" or "fifteen". This does not mean that the piraha can't count, because the presentation about the unit they have is still there. They see that fish in the boat was more or less, but the solution to arithmetic problems about the fish shop it would be completely absurd occupation.

For this reason, the piraha have no myths or stories about creation, the origin of man, animals or plants. The people of the tribe often tell each other stories, and some of them even are not devoid of narrative skill. But it can only be stories from their lives, something seen with my own eyes.

When Everett was sitting with one of the Indians, and told him about the Christian God, he asked him:

— What else does your God do?

Well, he created the stars and the earth, ' I said, and then asked himself:

— What do they say about the piraha people?

— Well, the piraha people say it's all nobody was created, he said.

Daniel Everett with the piraha Indians. Source: hercampus.com

Because of the principle of direct perception of piraha failed to convert to Christianity. In our religions, tells about the events, witnesses who have long departed to another world, so to Express these stories in the language of piraha is simply impossible. At the beginning of his mission, Everett was convinced that the spiritual message he carries to the Indians, is absolutely universal. Permeated their language and way of perceiving the world, he realized that it is not so.

Even if we accurately translate the New Testament into the language of the piraha and make sure that every word for them is clear, this does not mean that our story will have meaning for them. While the piraha believe that can see the spirits that come to the village and talk to them. For them, these spirits are not less real than the Indians themselves. This is further evidence of the limitations of our common sense. What is ordinary for us has no meaning for others.

Everett argues that his findings refute the hypothesis of universal grammar of Noam Chomsky that all languages have a basic component — a certain deep structure, the possession of which is inherent in human biology. The fact that this hypothesis tells us nothing about the relationship of language, culture and thinking. It does not explain why we so often do not understand each other."For those of us who do not believe in spirits, it seems absurd that you can see them. But this is just our point of view". One of the basic components of any language, according to Chomsky, recursion is. It makes possible such statements as "bring me nails that brought Dan" or "friend's house hunter". Piraha can easily do without such structures. Instead, they use chains of simple sentences: "Bring me nails. Nails brought Dan." It turns out that recursion is present, but not at the level of grammar but at the level of cognitive processes. The most basic elements of thinking are expressed in different languages in different ways.

Photo of one of the experiments. Source: sciencedaily.com

In "Philosophical investigations" Ludwig Wittgenstein suggests: if a lion could talk we wouldn't understand him. Even if we learn the lion's language, it does not necessarily make his statements understandable to us. There is no universal language — a particular "form of life" with common ways to think, act and speak.

Even mathematics seems universal not because of its intrinsic properties, but only because we all teach the multiplication table. This observation is clearly confirmed by the experiments of Soviet psychologists conducted in the 30-ies of the last century under the leadership of Alexander Luria and Lev Vygotsky. Approval type "A is B B is C therefore A is C" does not have universal nature. Without schooling to anybody and in a head has not come, that about something to do, you can talk in this way.

Consider at first glance a simple and innocent statement: "the Cat is on the Mat". It would seem, understand this statement and test its validity easy: it is enough to look around and make sure the four-legged furry creature is the subject, which we call the Mat.

From this point of view does not mean that language determines thinking, as claimed by the "strong version of" linguistic relativity hypothesis. Language and behaviour jointly determine each other. If your friend says "fuck you to hell" after you gave him a little tip for you, that might mean "Thanks, buddy, I'll do that," but to outside observers, this form of gratitude will sound at least strange.

Now imagine (as it is offered by Oleg Kharkhordin and Vadim Volkov in the book "Theory of practices") that cats and mats are participating in some alien ritual distant to us culture. In this tribe arrives to the researcher, but the ritual isn't allowed because it is prohibited by the gods. Scientist conscientiously tries to understand the meaning of the ritual according to their informants. He said that the climax of the rite "the cat is on the Mat".

Gathering the necessary data, the researcher returns home. But he may not know that because of the difficulties of the rite shamans have long used the dried stuffed cats that can balance on the tail; carpets-mats roll into a tube and placed on end, and on top, placed a dead cat balanced on his tail. Still hold true the statement "the cat is on the Mat"? Yes, but its meaning has changed dramatically.

The art of communication: WHAT we say and HOW we understandGraham hill: Less stuff — more happiness

To understand aliens, the heroine of "Arrival" had to change their views over time. To understand the piraha, Daniel Everett had to give up the belief that his faith is universal. To understand each other, we need to be able to put their views on reality into question.

Talk to relatives, colleagues or neighbors, of course, is easier than semenovii aliens or the Amazonian Indians. But to make concessions to someone else's common sense to understand others and be understood, we still have to constantly.published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

Source: newtonew.com/overview/linguistics-of-misunderstanding