608

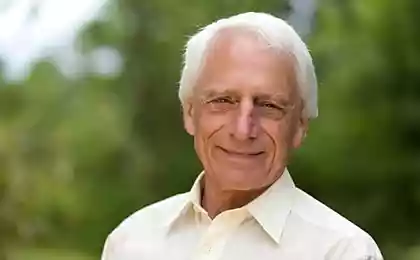

Michael Mosley —free will is just a myth

We are vain; we see ourselves as better than we are. We like to think that we exercise free will, that being in a situation where we have to do something unacceptable to us, we will refuse to do it. But if you think so, maybe wrong.

I say this partly based on the work of psychologist Stanley Milgram. Milgram devised and carried out ingenious experiments that exposed weakness and self-deception that accompany us in our daily lives. He showed how easy it is to make ordinary people do terrible things, fully control their minds.

The first time I read about the works of Milgram in the seventies, I was a banker and worked in the city (the business part of London). I was so passionate about his ideas that went to study again, this time at the doctor, and was going to become a psychiatrist. Instead, I became a science journalist. Recently I had the chance to work on the television series "the Brain: a secret History", which shows how much we have learned about myself with the help of one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century.

Working on the series we found rare archive, which were presented information first-hand about the many inventive and sometimes sinister ways to study, control and manipulate human behavior. Commending Stanley Milgram as a psychologist, I wanted to know more about who he was.

The son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Milgram was trying to understand how it happened that German soldiers during the Second world war took part in the barbaric killings of people. He once wrote: "How is it possible, I asked myself, that ordinary people in everyday life behave politely and with dignity, can act so rude, so inhuman, and they do not restrain the conscience."

Milgram worked as assistant Professor at Yale University in 1960, when he came up with an experiment that might answer this question. He was incredible in order to show the uncomfortable truth about human nature.

Some argue that the results of Milgram ethically and scientifically questionable. Personally, I always thought that they were justified, and very important, but I never had the chance to interview none of "volunteers" who unwittingly participated in his controversial experiments to hear their point of view.

Last summer, almost 50 years after the original experiment, I finally met one of the few remaining survivors, bill Menaldum. I spoke with bill in his kitchen, surrounded by his grandchildren, who also wanted to hear the story.

In 1961 bill Menaldo was 23 years old, and he just was discharged from the army. "I accidentally saw the announcement where it was written: take part in the experiment, and you'll be paid $ 4. And then I thought, why not try it?"

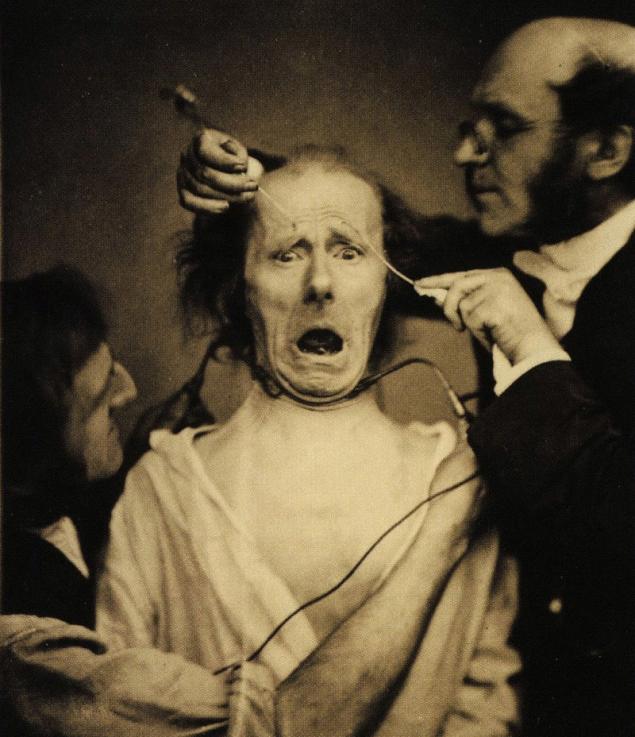

He went to the building where it met a serious young man in a white lab coat experimenter, and volunteers around middle age. The experimenter told bill that he would be the teacher and the rest of his disciples. The task of the teacher was to give the student a simple task, which it will then be tested. If the student answer incorrectly, the teacher will impress his electric shock. If he continues to give incorrect answers, the force of the shocks will increase.

Bill stayed in the room with a microphone and a set of electric controls. The student was introduced to another room, where bill could hear him, but not seen. Then the experiment began. The student was stupid.

"Wrong — 150 volts".

Bill was sitting at the table, and did what he was asked to do. Despite the cries coming from another room, he continued to ask questions, and involved the shock, when the student answered incorrectly.

"Wrong — 195 volts".

Even now it's hard to explain what happened to him that day. "You sit in a chair, around all of this is happening, and you are so depressed that it was difficult to think clearly. Neither before nor after I did not experience anything like that. I literally ceased to be himself."

"Wrong — 350 volts".

"I just told myself, could bring his role to the end, and leave soon. And I brought her. I didn't care what happened. Once something is decided, you stick to your decision. I just wanted to go home. Just wanted to get out, then drink the beer, and go home, you know?

"Wrong — 450 volts".

When I asked him whether he thought it killed a student, bill replied, "Yes. When he stopped responding".

The bill, as and other volunteers, participated in the experiment, said that as the experimenter with the pupil, and the electric shocks were fake. The real purpose of the experiment was to find out how to lead volunteers. Stanley Milgram asked his colleagues, how in their opinion the person could use deadly discharge 450 volts. Most said less than 1 percent, and these people probably would have been psychopaths.

However, the bill, as and 65 percent of other volunteers turned deadly discharge when they were told to do it.

I remember thinking when I first read it, that this figure is simply impossible. I was absolutely sure of it, and I think that anyone who has read the works of Milgram, was also sure that I never turned the switch to give a fatal charge, just because someone is power is ordered. It is impossible to imagine to be manipulated in this way.

Perhaps, I thought, somewhere deep down, the volunteers realized that this is not a real experiment that everyone plays a role. When critics pointed out at this point, Milgram sarcastically replied, "the Assumption that sweating, trembling and stammering, the subjects pretended to be to please divorced from reality the experimenter still the same statement that hemophiliacs bleed to death just so their doctors can have something to do".

Milgram argued that not being even to a small extent tampered with his experiment ruthlessly revealed something that as we all know sometimes happens, but I can't bring myself to believe it. Very convenient to imagine that it was some kind of unique evil or the weakness of the German prison camp and the guards, than to realize that most of us would behave the same if I were in this situation. "One of the illusions about human behavior is that it is associated with personality and character, but social psychology shows us that human behavior is often determined by the role that he is determined to play."

The bill was surprisingly optimistic about the fact that he had been deceived, and he is very honest about everything, it was especially telling about the moment when he abandoned his morals, and gave what is happening under the responsibility of the experimenter. From the height of the wisdom of the past years he was able to admire the care and skill with which the experiment has been conducted and how the participants played their roles.

I think a more justified criticism, rather than just the assertion that, say, "the experiment was a fake" would be the question of the conformity of experiment to the real world. Maybe people behave because they understood the artificiality of the situation? In 1996, inspired by Milgram's experiments, the psychiatrist Charles Hofling have developed a more realistic scenario.

He called 22 who worked in a big hospital the nurses seemed to them simply as "Dr. Smith" and say that each of them gave 20 milligrams of drugs called Astroman, the patient, whose name he called. Also Dr. Smith talked nurses that he was already on the way to the hospital, and he would sign all the necessary papers when you arrive.

The remedy, which was the invention of the experimenters, a few days before the phone call, along with a warning that 10 milligrams of medication are the maximum allowable dose, were put in the closet with lekarstvi. Despite this, and the fact that hospital protocols, it was noted that no drug should not be anyone to give only on the basis of a telephone call, 21 of the 22 two nurses was ready to give 20 milligrams of the drug when they were stopped. Nurses were subordinate to the authority of the "doctor".

Of course long before Milgram's experiments and Hofling it was known that people tend to blindly follow orders if they are given to someone who apparently has the power to give them. And these experiments revealed was just how strong this trend is. Psychology, which is often criticized for not so obvious things that shows that she is capable of making surprising, original and disturbing contribution to our understanding of ourselves.

Some professional organizations, like the U.S. army responded to these results the fact that include them into their workouts to be sure that future officers are aware of the pressure that can give orders, the execution of which, in their opinion, is unethical. Future doctors and nurses now also teach the dangers of blind execution of orders.

Other organizations, like the American society of Psychologists, responded to criticism of Milgram's methods by the adoption of the new guidelines when working with volunteers in the framework of the psychological experiments. I also believe that Milgram contributed to the spread of the critical view of power that characterized his era — the 60s years of the 20th century.

Own motivation for Milgram's experiments was not distrust of authority, and a desire to understand why the authority has on people, that effect. Continuing his research he went to the street to see how people will behave in a situation where apparent authority is missing.

Milgram went with his students in the new York subway. The objective of the experiment was to approach the passengers on the train, and politely tell them, "I would like you to give me his seat, please." As Milgram himself noted beforehand, "if you asked a new Yorker, conceded he would place another person, if he asked about it, not having apparent reason, he would have said "no". But how would he do in reality?" The answer was that in half of the cases people still lost their place if they asked you to do.

Recently, I decided to repeat this experiment in a busy London shopping centre, with similar results. I was surprised at how many people complied with my completely unreasonable request, but was even more surprised by how uncomfortable I felt, speaking to him with such a request, as Milgram also mentioned.

"I was going to say, "excuse me sir, give me the place?" but was surprised to find a kind of lethargy, the words simply stuck in my throat, and I couldn't pronounce. There was a monstrous barrier that must be overcome to utter this phrase".

Although it was unexpected, Milgram felt that this is a very important finding. In his own experience he found out how ill at ease feeling when you start to change behavior. We don't like to break social norms — asking for someone to give him a place or not obeying the orders of someone who once identified as authority.

In everyday life there are unwritten rules about who is responsible for what, and if we violate these rules, this leads to a feeling of uneasiness and embarrassment are so strong that we prefer to surrender, if circumstances so require. Of course it is very bad that we would rather let something terrible happen than act in a socially unacceptable manner. But it helps to explain some blood-curdling crime when someone attacks someone in a public place, and even kills, but no one intervenes.

Now I would like to believe that as a society, we are using the lessons taught to us by Milgram, become less blindly follow the requirements of the authority. I would like to believe it, but I don't.

Milgram's biographer, Dr. Thomas Blass recently asked myself the same question. "Would Milgram find less obedience if he conducted his experiments today? I doubt it. To go beyond speculation on this question, I gathered all standard experiments on obedience conducted by other researchers. The experiments spanned a 25-year period from 1961 to 1985.

"I conducted a correlation analysis for each year of the research, as well as the number of cases of subordination, revealed in the course of these studies. No correlation I have found. In other words, in later studies the number of cases of subordination was approximately the same."

There is a very recent example of a continuing trend of blind obedience in the United States, when fraud, nicknamed the "modern Milgram", forced the staff of dozens of fast food restaurants to do dirty things when you just called the restaurant, and presented by a police officer.

He convinced the managers to strip-search their employees who allegedly stole something, forced them to undress and naked to appear in front of frightened customers. One Manager, who searched employees, and was subsequently jailed, said, "I didn't mean to do it, but it was as if he was acting me."

Milgram once wrote that we are "puppets, which the company pulling the strings". However, it is also true that not all of the puppets start to dance when their strings are pulled. Many managers of fast food restaurants, which are called "police" and refused to follow his orders. In his own Milgram experiment, although it turned out that 65% of volunteers were ready to turn lethal voltage, however, 35 percent of the people refused to do it.

What the experimenter is still not able to determine, is, who of the volunteers will oppose. The only way to know how to behave you this one day to discover that you carried out the experiment. The fact that you get 1 chance to 2.

source: mixednews.ru

Source: /users/1077

I say this partly based on the work of psychologist Stanley Milgram. Milgram devised and carried out ingenious experiments that exposed weakness and self-deception that accompany us in our daily lives. He showed how easy it is to make ordinary people do terrible things, fully control their minds.

The first time I read about the works of Milgram in the seventies, I was a banker and worked in the city (the business part of London). I was so passionate about his ideas that went to study again, this time at the doctor, and was going to become a psychiatrist. Instead, I became a science journalist. Recently I had the chance to work on the television series "the Brain: a secret History", which shows how much we have learned about myself with the help of one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century.

Working on the series we found rare archive, which were presented information first-hand about the many inventive and sometimes sinister ways to study, control and manipulate human behavior. Commending Stanley Milgram as a psychologist, I wanted to know more about who he was.

The son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Milgram was trying to understand how it happened that German soldiers during the Second world war took part in the barbaric killings of people. He once wrote: "How is it possible, I asked myself, that ordinary people in everyday life behave politely and with dignity, can act so rude, so inhuman, and they do not restrain the conscience."

Milgram worked as assistant Professor at Yale University in 1960, when he came up with an experiment that might answer this question. He was incredible in order to show the uncomfortable truth about human nature.

Some argue that the results of Milgram ethically and scientifically questionable. Personally, I always thought that they were justified, and very important, but I never had the chance to interview none of "volunteers" who unwittingly participated in his controversial experiments to hear their point of view.

Last summer, almost 50 years after the original experiment, I finally met one of the few remaining survivors, bill Menaldum. I spoke with bill in his kitchen, surrounded by his grandchildren, who also wanted to hear the story.

In 1961 bill Menaldo was 23 years old, and he just was discharged from the army. "I accidentally saw the announcement where it was written: take part in the experiment, and you'll be paid $ 4. And then I thought, why not try it?"

He went to the building where it met a serious young man in a white lab coat experimenter, and volunteers around middle age. The experimenter told bill that he would be the teacher and the rest of his disciples. The task of the teacher was to give the student a simple task, which it will then be tested. If the student answer incorrectly, the teacher will impress his electric shock. If he continues to give incorrect answers, the force of the shocks will increase.

Bill stayed in the room with a microphone and a set of electric controls. The student was introduced to another room, where bill could hear him, but not seen. Then the experiment began. The student was stupid.

"Wrong — 150 volts".

Bill was sitting at the table, and did what he was asked to do. Despite the cries coming from another room, he continued to ask questions, and involved the shock, when the student answered incorrectly.

"Wrong — 195 volts".

Even now it's hard to explain what happened to him that day. "You sit in a chair, around all of this is happening, and you are so depressed that it was difficult to think clearly. Neither before nor after I did not experience anything like that. I literally ceased to be himself."

"Wrong — 350 volts".

"I just told myself, could bring his role to the end, and leave soon. And I brought her. I didn't care what happened. Once something is decided, you stick to your decision. I just wanted to go home. Just wanted to get out, then drink the beer, and go home, you know?

"Wrong — 450 volts".

When I asked him whether he thought it killed a student, bill replied, "Yes. When he stopped responding".

The bill, as and other volunteers, participated in the experiment, said that as the experimenter with the pupil, and the electric shocks were fake. The real purpose of the experiment was to find out how to lead volunteers. Stanley Milgram asked his colleagues, how in their opinion the person could use deadly discharge 450 volts. Most said less than 1 percent, and these people probably would have been psychopaths.

However, the bill, as and 65 percent of other volunteers turned deadly discharge when they were told to do it.

I remember thinking when I first read it, that this figure is simply impossible. I was absolutely sure of it, and I think that anyone who has read the works of Milgram, was also sure that I never turned the switch to give a fatal charge, just because someone is power is ordered. It is impossible to imagine to be manipulated in this way.

Perhaps, I thought, somewhere deep down, the volunteers realized that this is not a real experiment that everyone plays a role. When critics pointed out at this point, Milgram sarcastically replied, "the Assumption that sweating, trembling and stammering, the subjects pretended to be to please divorced from reality the experimenter still the same statement that hemophiliacs bleed to death just so their doctors can have something to do".

Milgram argued that not being even to a small extent tampered with his experiment ruthlessly revealed something that as we all know sometimes happens, but I can't bring myself to believe it. Very convenient to imagine that it was some kind of unique evil or the weakness of the German prison camp and the guards, than to realize that most of us would behave the same if I were in this situation. "One of the illusions about human behavior is that it is associated with personality and character, but social psychology shows us that human behavior is often determined by the role that he is determined to play."

The bill was surprisingly optimistic about the fact that he had been deceived, and he is very honest about everything, it was especially telling about the moment when he abandoned his morals, and gave what is happening under the responsibility of the experimenter. From the height of the wisdom of the past years he was able to admire the care and skill with which the experiment has been conducted and how the participants played their roles.

I think a more justified criticism, rather than just the assertion that, say, "the experiment was a fake" would be the question of the conformity of experiment to the real world. Maybe people behave because they understood the artificiality of the situation? In 1996, inspired by Milgram's experiments, the psychiatrist Charles Hofling have developed a more realistic scenario.

He called 22 who worked in a big hospital the nurses seemed to them simply as "Dr. Smith" and say that each of them gave 20 milligrams of drugs called Astroman, the patient, whose name he called. Also Dr. Smith talked nurses that he was already on the way to the hospital, and he would sign all the necessary papers when you arrive.

The remedy, which was the invention of the experimenters, a few days before the phone call, along with a warning that 10 milligrams of medication are the maximum allowable dose, were put in the closet with lekarstvi. Despite this, and the fact that hospital protocols, it was noted that no drug should not be anyone to give only on the basis of a telephone call, 21 of the 22 two nurses was ready to give 20 milligrams of the drug when they were stopped. Nurses were subordinate to the authority of the "doctor".

Of course long before Milgram's experiments and Hofling it was known that people tend to blindly follow orders if they are given to someone who apparently has the power to give them. And these experiments revealed was just how strong this trend is. Psychology, which is often criticized for not so obvious things that shows that she is capable of making surprising, original and disturbing contribution to our understanding of ourselves.

Some professional organizations, like the U.S. army responded to these results the fact that include them into their workouts to be sure that future officers are aware of the pressure that can give orders, the execution of which, in their opinion, is unethical. Future doctors and nurses now also teach the dangers of blind execution of orders.

Other organizations, like the American society of Psychologists, responded to criticism of Milgram's methods by the adoption of the new guidelines when working with volunteers in the framework of the psychological experiments. I also believe that Milgram contributed to the spread of the critical view of power that characterized his era — the 60s years of the 20th century.

Own motivation for Milgram's experiments was not distrust of authority, and a desire to understand why the authority has on people, that effect. Continuing his research he went to the street to see how people will behave in a situation where apparent authority is missing.

Milgram went with his students in the new York subway. The objective of the experiment was to approach the passengers on the train, and politely tell them, "I would like you to give me his seat, please." As Milgram himself noted beforehand, "if you asked a new Yorker, conceded he would place another person, if he asked about it, not having apparent reason, he would have said "no". But how would he do in reality?" The answer was that in half of the cases people still lost their place if they asked you to do.

Recently, I decided to repeat this experiment in a busy London shopping centre, with similar results. I was surprised at how many people complied with my completely unreasonable request, but was even more surprised by how uncomfortable I felt, speaking to him with such a request, as Milgram also mentioned.

"I was going to say, "excuse me sir, give me the place?" but was surprised to find a kind of lethargy, the words simply stuck in my throat, and I couldn't pronounce. There was a monstrous barrier that must be overcome to utter this phrase".

Although it was unexpected, Milgram felt that this is a very important finding. In his own experience he found out how ill at ease feeling when you start to change behavior. We don't like to break social norms — asking for someone to give him a place or not obeying the orders of someone who once identified as authority.

In everyday life there are unwritten rules about who is responsible for what, and if we violate these rules, this leads to a feeling of uneasiness and embarrassment are so strong that we prefer to surrender, if circumstances so require. Of course it is very bad that we would rather let something terrible happen than act in a socially unacceptable manner. But it helps to explain some blood-curdling crime when someone attacks someone in a public place, and even kills, but no one intervenes.

Now I would like to believe that as a society, we are using the lessons taught to us by Milgram, become less blindly follow the requirements of the authority. I would like to believe it, but I don't.

Milgram's biographer, Dr. Thomas Blass recently asked myself the same question. "Would Milgram find less obedience if he conducted his experiments today? I doubt it. To go beyond speculation on this question, I gathered all standard experiments on obedience conducted by other researchers. The experiments spanned a 25-year period from 1961 to 1985.

"I conducted a correlation analysis for each year of the research, as well as the number of cases of subordination, revealed in the course of these studies. No correlation I have found. In other words, in later studies the number of cases of subordination was approximately the same."

There is a very recent example of a continuing trend of blind obedience in the United States, when fraud, nicknamed the "modern Milgram", forced the staff of dozens of fast food restaurants to do dirty things when you just called the restaurant, and presented by a police officer.

He convinced the managers to strip-search their employees who allegedly stole something, forced them to undress and naked to appear in front of frightened customers. One Manager, who searched employees, and was subsequently jailed, said, "I didn't mean to do it, but it was as if he was acting me."

Milgram once wrote that we are "puppets, which the company pulling the strings". However, it is also true that not all of the puppets start to dance when their strings are pulled. Many managers of fast food restaurants, which are called "police" and refused to follow his orders. In his own Milgram experiment, although it turned out that 65% of volunteers were ready to turn lethal voltage, however, 35 percent of the people refused to do it.

What the experimenter is still not able to determine, is, who of the volunteers will oppose. The only way to know how to behave you this one day to discover that you carried out the experiment. The fact that you get 1 chance to 2.

source: mixednews.ru

Source: /users/1077