192

The place where willpower lives, and the mind-blowing case of its loss

Lack of willpower is a frequent companion of failures and disappointments in life. Most people believe that willpower is either given to a person or not, and nothing can be done about it.

From a certain point of view, there is a rational grain in this, because thanks to research by neuroscientists, it was found that the prefrontal cortex is responsible for volitional decisions.

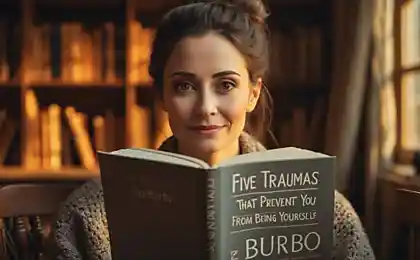

However, as Stanford University professor Kelly McGonigal convincingly proves in his best-selling book Willpower. How to develop and strengthen, willpower is not a forever set parameter. Willpower is amenable to change and development. True with a caveat – if your brain is fine and it works like most normal people.

The prefrontal cortex (nerve centers at the level of the forehead and eyes) is designed to coordinate our desires, control thoughts, feelings and actions. Neuroscientists at Stanford University have shown that “the main task of the modern prefrontal cortex is to incline the brain to what is more difficult.” When it's easier to lie on the couch, your prefrontal cortex makes you want to get up and run.

The prefrontal cortex has three different zones:

"I will," "I will," "I will not."

Each of them performs its task - to protect you from making impulsive decisions, to help start doing uninteresting things or to quit what is not useful.

The first force is "I won't."

For example, I will not drink, smoke, eat after six, go to bed late.

The second force is "I will."

It is used when you need to do what you do not want: go to work, wake up on the alarm clock, make a morning run.

The third force is "I want."

It is the ability to remember what you really want. Remembering this, the phrases “I will not smoke” and “I will go to the gym” are transformed into “I want to be healthy and strong.”

Self-control is the control of all three forces. And it's only possible if we use a unique human ability. self-awareness.

Some of our conditions (intoxication, fatigue) suppress the activity of the prefrontal cortex, and it becomes more difficult for us to control ourselves and restrain our impulses. Also, lack of control and loss of self-control lead to damage to the prefrontal cortex as a result of injuries, accidents and diseases. Kelly McGonigal talks about perhaps the most famous case of damage to this area of the brain.

In 1848 Phineas Gage commanded a brigade of railway workers at the age of 24. His subordinates considered him the best foreman, respected and loved him. Friends and family described him as a calm, balanced person. The personal physician, John Martin Harlow, reported that the ward was strong in body and spirit, “possessed of iron will and steel muscles.”

But that all changed on Wednesday September 13 at 4:30 p.m. Gage and his crew cleared the way with explosives to build a railroad between Burlington and Rutland in Vermont. Gage was laying charges. The procedure had been repeated a thousand times, but suddenly something went wrong. The explosion occurred too early, and a meter-long tramp pierced Gage's skull. She went into her left cheek, pierced her frontal lobes and landed 30 meters away, taking some gray matter with her.

You may have imagined that Gage suffered instant death. But no, Gage's not dead. According to eyewitnesses, he did not even pass out. The workers simply put him on a wheelbarrow and pushed him two kilometers to the tavern where he was staying. The doctor carefully patched Gage, returning to the place large fragments of the skull collected from the scene, and applied stitches.

It took Gage more than two months to fully recover physically (possibly he was hampered in many ways by Dr. Harlow’s radical appointments: he prescribed enemas from a fungus that appeared on open areas of Gage’s brain). By November 17, the patient was well enough to return to life. Gage himself stated that he felt better in every sense and the pain did not torment him.

Sounds like a happy ending. But Gage was unlucky: his story doesn’t end there. The external wounds healed, but strange things were happening in the brain itself. According to friends and colleagues, Gage's character has changed. Dr. Harlow described the change in the medical report on the effects of the injury:

Perhaps there is a imbalance... between mental abilities and animal inclinations. He is impulsive, irreverent, sometimes allows himself the most bad swearing (than before he was not different), disrespectfully treats friends, does not accept restrictions and advice if they contradict his desires ... invents many plans for the future, but immediately loses interest in them ... In this sense, his mind has radically changed, so clearly that friends and acquaintances claim that it is no longer Gage.

In other words, along with the prefrontal cortex, Gage lost self-control: the powers of “I won’t” and “I will.” His iron will, which seemed to be an integral part of his character, was shattered by a tramp flying through his skull.

Most of us don’t have to worry about sudden train explosions that take away our self-control, but there’s a little Phineas Gage in everyone.

The prefrontal cortex is not as reliable as we would like. Some conditions — when we’re drunk, sleep-deprived, or just distracted — suppress it and mimic brain damage.The one Gage got. They make it harder for us to cope with our impulses, even if our gray matter is still safely hidden by the skull box.

Yes, we can all do things that are more difficult, but we also have the desire to do the opposite. This urge must be restrained, but it lives by its mind.

P.S. And remember, just changing our consumption – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: makeright.ru/blog/mesto-gde-zhivet-sila-voli/

From a certain point of view, there is a rational grain in this, because thanks to research by neuroscientists, it was found that the prefrontal cortex is responsible for volitional decisions.

However, as Stanford University professor Kelly McGonigal convincingly proves in his best-selling book Willpower. How to develop and strengthen, willpower is not a forever set parameter. Willpower is amenable to change and development. True with a caveat – if your brain is fine and it works like most normal people.

The prefrontal cortex (nerve centers at the level of the forehead and eyes) is designed to coordinate our desires, control thoughts, feelings and actions. Neuroscientists at Stanford University have shown that “the main task of the modern prefrontal cortex is to incline the brain to what is more difficult.” When it's easier to lie on the couch, your prefrontal cortex makes you want to get up and run.

The prefrontal cortex has three different zones:

"I will," "I will," "I will not."

Each of them performs its task - to protect you from making impulsive decisions, to help start doing uninteresting things or to quit what is not useful.

The first force is "I won't."

For example, I will not drink, smoke, eat after six, go to bed late.

The second force is "I will."

It is used when you need to do what you do not want: go to work, wake up on the alarm clock, make a morning run.

The third force is "I want."

It is the ability to remember what you really want. Remembering this, the phrases “I will not smoke” and “I will go to the gym” are transformed into “I want to be healthy and strong.”

Self-control is the control of all three forces. And it's only possible if we use a unique human ability. self-awareness.

Some of our conditions (intoxication, fatigue) suppress the activity of the prefrontal cortex, and it becomes more difficult for us to control ourselves and restrain our impulses. Also, lack of control and loss of self-control lead to damage to the prefrontal cortex as a result of injuries, accidents and diseases. Kelly McGonigal talks about perhaps the most famous case of damage to this area of the brain.

In 1848 Phineas Gage commanded a brigade of railway workers at the age of 24. His subordinates considered him the best foreman, respected and loved him. Friends and family described him as a calm, balanced person. The personal physician, John Martin Harlow, reported that the ward was strong in body and spirit, “possessed of iron will and steel muscles.”

But that all changed on Wednesday September 13 at 4:30 p.m. Gage and his crew cleared the way with explosives to build a railroad between Burlington and Rutland in Vermont. Gage was laying charges. The procedure had been repeated a thousand times, but suddenly something went wrong. The explosion occurred too early, and a meter-long tramp pierced Gage's skull. She went into her left cheek, pierced her frontal lobes and landed 30 meters away, taking some gray matter with her.

You may have imagined that Gage suffered instant death. But no, Gage's not dead. According to eyewitnesses, he did not even pass out. The workers simply put him on a wheelbarrow and pushed him two kilometers to the tavern where he was staying. The doctor carefully patched Gage, returning to the place large fragments of the skull collected from the scene, and applied stitches.

It took Gage more than two months to fully recover physically (possibly he was hampered in many ways by Dr. Harlow’s radical appointments: he prescribed enemas from a fungus that appeared on open areas of Gage’s brain). By November 17, the patient was well enough to return to life. Gage himself stated that he felt better in every sense and the pain did not torment him.

Sounds like a happy ending. But Gage was unlucky: his story doesn’t end there. The external wounds healed, but strange things were happening in the brain itself. According to friends and colleagues, Gage's character has changed. Dr. Harlow described the change in the medical report on the effects of the injury:

Perhaps there is a imbalance... between mental abilities and animal inclinations. He is impulsive, irreverent, sometimes allows himself the most bad swearing (than before he was not different), disrespectfully treats friends, does not accept restrictions and advice if they contradict his desires ... invents many plans for the future, but immediately loses interest in them ... In this sense, his mind has radically changed, so clearly that friends and acquaintances claim that it is no longer Gage.

In other words, along with the prefrontal cortex, Gage lost self-control: the powers of “I won’t” and “I will.” His iron will, which seemed to be an integral part of his character, was shattered by a tramp flying through his skull.

Most of us don’t have to worry about sudden train explosions that take away our self-control, but there’s a little Phineas Gage in everyone.

The prefrontal cortex is not as reliable as we would like. Some conditions — when we’re drunk, sleep-deprived, or just distracted — suppress it and mimic brain damage.The one Gage got. They make it harder for us to cope with our impulses, even if our gray matter is still safely hidden by the skull box.

Yes, we can all do things that are more difficult, but we also have the desire to do the opposite. This urge must be restrained, but it lives by its mind.

P.S. And remember, just changing our consumption – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: makeright.ru/blog/mesto-gde-zhivet-sila-voli/

The perfect drink to restore the acid-alkaline balance

A man after a divorce or the seventeenth of the month syndrome