320

Body Wisdom: 3 Techniques for Connecting with the Somatic Mind

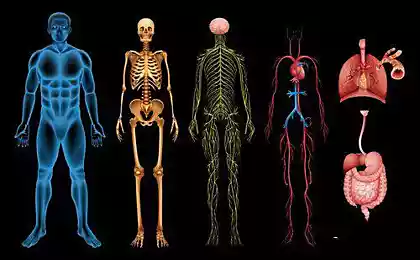

Somatic intelligence is our fundamental intelligence.

Not all creatures have a cognitive mind, but in order to survive and interact effectively with the environment, all living organisms need a somatic mind. Somatic intelligence is mammalian intelligence and the primary form of intelligence in young children.

Inside the body is a complete system of intelligence and wisdom. Sometimes we live in harmony with him, and sometimes not.

When we are in contact with our somatic mind, we live in the body.. This means that there is an important part of our consciousness in the body.

The body lives and breathes only in the present moment, and when we are in contact with our somatic knowledge, part of the consciousness is also anchored in the present moment. We may be engaged in the task we are solving, interaction, intellectual activity, or whatever, but our consciousness is simultaneously rooted in the body, in the ever-changing universe of physical sensations and feelings. This gives us access to a vast and resourceful repository of information that enriches our experience of everything we do.

When we say that someone is “living in the head” or “cut off from the body,” it indicates a lack of access to the vast world of somatic experience and intelligence. When we “live in our heads,” it usually means that we are not aware of the present moment and our body, that we have lost contact with them. Often this is accompanied by certain emotional or physical manifestations: breathing becomes shallow or rapid, we speak quickly, our shoulders, neck and face tense, we experience feelings of anxiety, stress or compression.

Conversely, when we are grounded in the body and in the present moment, we are physically relaxed, breathe slower and deeper, feel calm and experience resource states such as relaxed alertness and calm alertness.As Richard Moss points out, when the body is happy, our emotions are positive.My mind is calm. The subjective experience of somatic intelligence is known in all cultures, in all historical epochs, and is linguistically reflected in the classes of words, which in NLP are called the "language of organs." Organ language is a seemingly metaphorical statement or idiom associated with parts or functions of the body.

Expressions such as “I feel in my gut,” “I followed my heart,” or “I knew deep down” imply that intelligence is not only in the brain, but also in other parts of the body.. We also say that something “does not digest”, something “breaks our heart”, and something “exhausts all the intestines”. However, it is generally accepted in NLP that such expressions are not just metaphors. Like sensory predicates ("I see what you're saying," "I don't understand it," "it sounds convincing," "I touched it," "I feel it's right," and so on), organ language often reflects deep-seated "neuro-linguistic" patterns and processes that allow one to penetrate the deep structures of subjective experience.

Bodily sensation: a subjective experience of the somatic mind

Subjectively, we become aware of our somatic mind through what philosopher and psychotherapist Eugene Gendlin calls “felt sense.” It is based on his therapeutic method called focusing. Gendlin believes that the interaction of a living organism with its environment necessarily precedes a more abstract cognitive knowledge of that environment. According to Gendlin, life is a complex, orderly interaction with the environment and therefore life itself is a separate, special type of learning and knowledge. Abstract cognitive knowledge arises from this basic knowledge, which is the underlying structure of our conscious thought process.

Neurogastroenterology and the brain in the stomach

One type of brain in the body is called the enteric brain or enteric nervous system. ("entero" literally means "inside the intestine", from the ancient Greek enteron, "intestine"). This system contains 100 million neurons, more than the spine. According to modern neurology, the nervous system surrounding the colon and other digestive organs in the abdominal cavity has about the same complexity as the brain of a cat. It is called the second brain of the human body.

In recent years, a lot of data has emerged on how the enteric nervous system reflects the activity of the central nervous system.Dr. Michael Gershon, professor of anatomy and cell biology at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, is one of the founders of a new branch of medicine called neurogastroenterology. The Second Brain: How We “Feel Your Bowels” and a New Understanding of Psychosomatic and Nervous Diseases of the Stomach and Intestines (“The Second Brain: The Scientific Basis of Gut Instinct and a Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and Intestines”), Gershon argues that the gut brain is very important for human health and happiness, and also plays an important role in situations of discomfort and stress. Many digestive disorders, such as colitis and acute abdominal syndrome, are caused by problems in the enteric nervous system.

The enteric nervous system controls various aspects of digestion, from the esophagus to the stomach, then to the small intestine and colon. Neurogastroenterologists also believe that there is a complex interaction between the enteric nervous system and the immune system.

Biologists believe that during the evolution of mammals, the enteric nervous system was too important. Therefore, it is not located in the head of the newborn - in this case, too long connections between the head and the abdominal cavity would be required. The baby needs to eat and digest food from birth. Therefore, the process of evolution may have preserved the enteric nervous system as an independent chain. It is interesting to note that during the development of the human embryo, a fragment of tissue called the “nerve roller” is formed in the early stages. One segment forms the central nervous system, while the other migrates and forms the enteric nervous system. According to Dr. Gershon, communication between these systems occurs much later, through the vagus nerve. It is connected to the central nervous system, but for the most part is able to function on its own, without brain control.

The brain in the abdomen receives and sends impulses, remembers experiences and responds to emotions with the same neurotransmitters as brain cells. Neurons of the enteric nervous system are located in “capsules” of tissue along the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon. As a single organ, it is a network of neurons, neurotransmitters and proteins that transmit messages between neurons, its cells are like brain cells and form a complex network that allows it to act independently, learn and remember, thanks to which we can “feel gut”.

So we have a kind of cat brain in our stomach. When a cat is happy, it purrs. But if something threatens her, she hisses, "Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!" When the central nervous system faces a threatening situation, it releases stress hormones into the bloodstream.Prepare the body to respond to stress: fight or run. There are many sensory nerves in the intestine system that stimulate the production of these chemicals, and then we feel like we are “nervous.”

Modern research also shows that stress, especially in early life, can cause chronic gastroenterological disorders. According to some reports, about 70% of patients who complain of chronic gastro-enterological diseases experienced trauma in childhood, such as the loss of one of their parents, a serious illness, the death of significant others.

It is interesting to note that in the traditional cultures of all continents it was believed that the stomach is a sacred “house of the soul”. In Japanese martial arts, Chinese medicine, dances of Africa, India, Polynesia, North American Indians, the peoples of the Middle East and Europe, there are practices for activating the abdominal energy to awaken the “soul-power” in the center of the body. The center of the abdomen, which the Japanese call the word hara, in many martial arts and healing practices is considered the "nucleus" of the body, both physical and energetic. It is the center of strength and balance, covering several organs of the body. In the hare, the legs begin, linking it to the ground, creating grounding and allowing us to move. Moreover, hara is considered the source of life and a kind of spiritual center. Its development helps to achieve skill, strength, wisdom and peace.

In Japanese, the word hara denotes both the abdomen and the qualities of character that arise when a person activates the “vital force” concentrated in the abdomen.

In Japanese, there are phrases that contain the word hara and indicate the importance of the belly for a full and prosperous life. For example, the “art of the belly” is any action that is performed completely and effortlessly. "Great belly" - a person, broad-minded, understanding, compassionate and generous. A clean belly is a person with a clear consciousness. “Finding your stomach” means clearly defining your intentions. “Beat the drum of the stomach” – to be satisfied with your life.

The Hara Man is someone who lives creatively, boldly, confidently, purposefully, holistically and persistently. Hara no aruhito literally means “centered” or “he has a belly.” Such a person is balanced, relaxed, generous and kind-hearted. He is calm, does not judge others, he knows what is important, accepts things as they are, and he has a sense of harmony and proportion. He is ready for anything that may be waiting on his way. When, through perseverance, discipline, and practice, such a person reaches maturity, he is called hara no dekita chito, the one who has finished his belly.

In Chinese, the center of the abdomen is called Dantian. The word literally means the field that must be cultivated to grow a crop that sustains life. That is, when a person activates the center of his body through movement and breathing, he gets access to the center of his being, the soul-power and the inner source.

Obviously, these linguistic expressions reflect the intuitive understanding and subjective experience associated with the fact that the “mind in the stomach” is an essential element of our somatic intelligence and a powerful resource.

Below is a simple exercise that can be used to establish and strengthen a connection with the “mind in the stomach.”

Neurocardiology and the brain in the heart

Just like the enteric nervous system, the heart’s complex circuitry allows it to act independently of the brain in the head – learning, remembering, and even feeling. A recent book, Basic and Clinical Neurocardiology, edited by Dr. Andrew Armour and Dr. Jeffrey Ardell, provides a comprehensive overview of the functions of the autonomic nervous system of the heart and the role of central and peripheral neurons in the regulation of cardiac function.

One of the pioneers of neurocardiology, Dr. Armour, shows that the heart has an internal nervous system complex enough to call it a separate “little brain.” The heart’s nervous system contains about 40,000 neurons called sensory axons. They capture circulating hormones and neurochemicals and track heart rate and blood pressure. Information about hormones, chemicals, heart rate and pressure is translated into neurological impulses by the heart’s nervous system and sent to the brain.

Thus, the heart has its own internal nervous system, acting and processing information independently of the brain or central nervous system. This is why the transplanted heart works. Normally, the heart communicates with the brain through tissues located along the vagus nerve and spinal column. In a transplanted heart, these nerve connections regenerate very slowly, if at all. However, a transplanted heart can function in a new home because it has its own holistic nervous system.

The reports of many heart transplant patients provide surprising evidence that the “heart brain” is capable of storing memories and influencing behavior. For example, Dr. Mario Alonso Pugh, a general practitioner (and abdominal surgery) surgeon, has been a leading surgeon at Harvard Medical School for more than twenty-five years and a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He reports one patient with a heart transplant. After the operation, the patient exhibited unusual behavior. He loved dishes he had never loved before. He became a fan of music he had never liked before. He was drawn to places he did not know or remember.

The mystery was revealed when doctors found out what kind of life was led by the donor, whose heart was transplanted to the patient. It turned out that the patient began to love the food that the donor preferred; in addition, the donor was a musician and played in a style that the patient suddenly loved, and the places in which the patient was drawn were iconic in the life of the donor. Due to strict privacy rules, neither the patient nor the doctors had access to the donor’s information or personal history. Perhaps somehow the donor's preferences were passed on to the patient along with his heart.

All these examples seem to confirm that the heart is a complex and mysterious organ, not just a blood pumping muscle.

Like the belly, the heart has always been considered an important center of knowledge and feeling. Some of the earliest known civilizations, including Ancient Greece, Mesopotamia, and Babylon, believed the heart to be the seat of intelligence. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote that the heart is the most important organ of the body and all nerves begin in it. Interestingly, according to his observations, this is the first organ that is formed in a chicken embryo. Aristotle believed that it is the center of intelligence, movement and sensation – the center of the vital force of the body.

Recently, various research groups are developing ways to penetrate the “brain” of the heart, especially the HeartMath Institute in Bouldercrick, California. Claiming that “the heart is the most powerful source of rhythmic informational images in the human body,” HeartMath researchers state: “As the most important interconnection center for many body systems, the heart is the single most powerful entry point into the network of communications connecting body, mind, emotion and spirit.”

HeartMath’s approach is based on the understanding that the heart interacts with the body and brain in four ways:

1. Neurologically – by transmitting nerve impulses through the vagus nerve and spine.

2. Biophysically - through the heartbeat. The heart sends energy in the form of blood pressure waves, also known as the pulse volume (BPV), which bring more or less concentration of blood supply to the cells of the body and brain. It was found that changes in the electrical activity of brain cells occur in accordance with changes in blood pressure waves.

3. Biochemically - through the release of neurotransmitters and hormonesFor example, such as atrial peptide, a hormone that slows the release of other stress hormones.

4. Energy-- through the electromagnetic fields generated by the heartbeat. An ECG used to measure the rhythm of the heartbeat, in particular, records the electrical signals emitted by the heart. These signals can not only be caught anywhere on the body, but also in the space around it.

HeartMath has developed a set of simple tools designed to help people connect with the intuitive intelligence of the heart brain and begin to gain support, expressed in the ability to better make decisions and use the wisdom of the heart to control the mind and emotions. A comprehensive study of these techniques, as well as their scientific basis, can be found in The HeartMath Solution (1999) by Doc Childre and Howard Martin. These tools have a lot in common with the main tools of NLP.

The simplest technique is called Freeze Frame. This is a one-minute procedure that can significantly change perception. It can be especially helpful in difficult or stressful situations. Below is a simple and brief summary of the sequence of actions:

1. Turn your attention from your thoughts to the area around your heart. Observe it for at least ten seconds while still breathing normally.

2. Think back to a positive experience or emotional state that you once experienced and relive it as fully as possible. See him, hear him and, most importantly, tune in to the sensory sensations in order to fully experience this state.

3. Ask your heart, “What can I do to change this situation?” or “What can I do to reduce stress?”

4. Listen to your heart’s response.

Even if you don’t hear anything, you’re likely to feel calmer and more relaxed. The answer can come not in words, but in the form of mental images or sensory sensation. You can get confirmation of something you already know, or you can look at it from a new, more harmonious perspective.

Cut-Thru is another HeartMath technique to help people better manage their emotions. Its goal is to help develop the ability to “release” complex long-standing emotional reactions, dynamically transform them and get out of dead ends.

1. Be aware of what you are feeling about a problem or situation by focusing on your heart.

2. Take an observer’s position on the situation. Act like it’s someone else’s problem. Think of yourself with third-person pronouns, i.e. “he” or “she” instead of “I” or “me.” What advice would you give yourself if you were a witness or mentor?

3. Imagine returning to your heart a distorted feeling or emotional energy that is in imbalance. Let it sink in there, as if you were plunging into a warm bath, so that it relaxes, blends and transforms. Practice trusting your heart to do the work for you.

The purpose of the release technique is to help people learn to accept, hold, and transform complex feelings instead of suppressing them.

The third tool, Heart Lock-In, helps you learn more about your heart in order to achieve physical, mental and spiritual recovery.

1. Shift your attention from your mind to your heart and let it stay there.

2. Remember the feeling of love, togetherness, or care that you feel easily toward someone. Focus on feeling grateful or grateful for someone or something positive. Practice being in this emotional state for five to fifteen minutes.

3. Take care to direct this feeling of love or appreciation to yourself and others.

This is not all that 3rd generation NLP calls the somatic mind. published

Author: Lyudmila Kolobovskaya

P.S. And remember, just changing our consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.b17.ru/blog/moi__psikholog__slovar_somatik_razum/

Not all creatures have a cognitive mind, but in order to survive and interact effectively with the environment, all living organisms need a somatic mind. Somatic intelligence is mammalian intelligence and the primary form of intelligence in young children.

Inside the body is a complete system of intelligence and wisdom. Sometimes we live in harmony with him, and sometimes not.

When we are in contact with our somatic mind, we live in the body.. This means that there is an important part of our consciousness in the body.

The body lives and breathes only in the present moment, and when we are in contact with our somatic knowledge, part of the consciousness is also anchored in the present moment. We may be engaged in the task we are solving, interaction, intellectual activity, or whatever, but our consciousness is simultaneously rooted in the body, in the ever-changing universe of physical sensations and feelings. This gives us access to a vast and resourceful repository of information that enriches our experience of everything we do.

When we say that someone is “living in the head” or “cut off from the body,” it indicates a lack of access to the vast world of somatic experience and intelligence. When we “live in our heads,” it usually means that we are not aware of the present moment and our body, that we have lost contact with them. Often this is accompanied by certain emotional or physical manifestations: breathing becomes shallow or rapid, we speak quickly, our shoulders, neck and face tense, we experience feelings of anxiety, stress or compression.

Conversely, when we are grounded in the body and in the present moment, we are physically relaxed, breathe slower and deeper, feel calm and experience resource states such as relaxed alertness and calm alertness.As Richard Moss points out, when the body is happy, our emotions are positive.My mind is calm. The subjective experience of somatic intelligence is known in all cultures, in all historical epochs, and is linguistically reflected in the classes of words, which in NLP are called the "language of organs." Organ language is a seemingly metaphorical statement or idiom associated with parts or functions of the body.

Expressions such as “I feel in my gut,” “I followed my heart,” or “I knew deep down” imply that intelligence is not only in the brain, but also in other parts of the body.. We also say that something “does not digest”, something “breaks our heart”, and something “exhausts all the intestines”. However, it is generally accepted in NLP that such expressions are not just metaphors. Like sensory predicates ("I see what you're saying," "I don't understand it," "it sounds convincing," "I touched it," "I feel it's right," and so on), organ language often reflects deep-seated "neuro-linguistic" patterns and processes that allow one to penetrate the deep structures of subjective experience.

Bodily sensation: a subjective experience of the somatic mind

Subjectively, we become aware of our somatic mind through what philosopher and psychotherapist Eugene Gendlin calls “felt sense.” It is based on his therapeutic method called focusing. Gendlin believes that the interaction of a living organism with its environment necessarily precedes a more abstract cognitive knowledge of that environment. According to Gendlin, life is a complex, orderly interaction with the environment and therefore life itself is a separate, special type of learning and knowledge. Abstract cognitive knowledge arises from this basic knowledge, which is the underlying structure of our conscious thought process.

Neurogastroenterology and the brain in the stomach

One type of brain in the body is called the enteric brain or enteric nervous system. ("entero" literally means "inside the intestine", from the ancient Greek enteron, "intestine"). This system contains 100 million neurons, more than the spine. According to modern neurology, the nervous system surrounding the colon and other digestive organs in the abdominal cavity has about the same complexity as the brain of a cat. It is called the second brain of the human body.

In recent years, a lot of data has emerged on how the enteric nervous system reflects the activity of the central nervous system.Dr. Michael Gershon, professor of anatomy and cell biology at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, is one of the founders of a new branch of medicine called neurogastroenterology. The Second Brain: How We “Feel Your Bowels” and a New Understanding of Psychosomatic and Nervous Diseases of the Stomach and Intestines (“The Second Brain: The Scientific Basis of Gut Instinct and a Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and Intestines”), Gershon argues that the gut brain is very important for human health and happiness, and also plays an important role in situations of discomfort and stress. Many digestive disorders, such as colitis and acute abdominal syndrome, are caused by problems in the enteric nervous system.

The enteric nervous system controls various aspects of digestion, from the esophagus to the stomach, then to the small intestine and colon. Neurogastroenterologists also believe that there is a complex interaction between the enteric nervous system and the immune system.

Biologists believe that during the evolution of mammals, the enteric nervous system was too important. Therefore, it is not located in the head of the newborn - in this case, too long connections between the head and the abdominal cavity would be required. The baby needs to eat and digest food from birth. Therefore, the process of evolution may have preserved the enteric nervous system as an independent chain. It is interesting to note that during the development of the human embryo, a fragment of tissue called the “nerve roller” is formed in the early stages. One segment forms the central nervous system, while the other migrates and forms the enteric nervous system. According to Dr. Gershon, communication between these systems occurs much later, through the vagus nerve. It is connected to the central nervous system, but for the most part is able to function on its own, without brain control.

The brain in the abdomen receives and sends impulses, remembers experiences and responds to emotions with the same neurotransmitters as brain cells. Neurons of the enteric nervous system are located in “capsules” of tissue along the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon. As a single organ, it is a network of neurons, neurotransmitters and proteins that transmit messages between neurons, its cells are like brain cells and form a complex network that allows it to act independently, learn and remember, thanks to which we can “feel gut”.

So we have a kind of cat brain in our stomach. When a cat is happy, it purrs. But if something threatens her, she hisses, "Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!" When the central nervous system faces a threatening situation, it releases stress hormones into the bloodstream.Prepare the body to respond to stress: fight or run. There are many sensory nerves in the intestine system that stimulate the production of these chemicals, and then we feel like we are “nervous.”

Modern research also shows that stress, especially in early life, can cause chronic gastroenterological disorders. According to some reports, about 70% of patients who complain of chronic gastro-enterological diseases experienced trauma in childhood, such as the loss of one of their parents, a serious illness, the death of significant others.

It is interesting to note that in the traditional cultures of all continents it was believed that the stomach is a sacred “house of the soul”. In Japanese martial arts, Chinese medicine, dances of Africa, India, Polynesia, North American Indians, the peoples of the Middle East and Europe, there are practices for activating the abdominal energy to awaken the “soul-power” in the center of the body. The center of the abdomen, which the Japanese call the word hara, in many martial arts and healing practices is considered the "nucleus" of the body, both physical and energetic. It is the center of strength and balance, covering several organs of the body. In the hare, the legs begin, linking it to the ground, creating grounding and allowing us to move. Moreover, hara is considered the source of life and a kind of spiritual center. Its development helps to achieve skill, strength, wisdom and peace.

In Japanese, the word hara denotes both the abdomen and the qualities of character that arise when a person activates the “vital force” concentrated in the abdomen.

In Japanese, there are phrases that contain the word hara and indicate the importance of the belly for a full and prosperous life. For example, the “art of the belly” is any action that is performed completely and effortlessly. "Great belly" - a person, broad-minded, understanding, compassionate and generous. A clean belly is a person with a clear consciousness. “Finding your stomach” means clearly defining your intentions. “Beat the drum of the stomach” – to be satisfied with your life.

The Hara Man is someone who lives creatively, boldly, confidently, purposefully, holistically and persistently. Hara no aruhito literally means “centered” or “he has a belly.” Such a person is balanced, relaxed, generous and kind-hearted. He is calm, does not judge others, he knows what is important, accepts things as they are, and he has a sense of harmony and proportion. He is ready for anything that may be waiting on his way. When, through perseverance, discipline, and practice, such a person reaches maturity, he is called hara no dekita chito, the one who has finished his belly.

In Chinese, the center of the abdomen is called Dantian. The word literally means the field that must be cultivated to grow a crop that sustains life. That is, when a person activates the center of his body through movement and breathing, he gets access to the center of his being, the soul-power and the inner source.

Obviously, these linguistic expressions reflect the intuitive understanding and subjective experience associated with the fact that the “mind in the stomach” is an essential element of our somatic intelligence and a powerful resource.

Below is a simple exercise that can be used to establish and strengthen a connection with the “mind in the stomach.”

- Sit comfortably, with a "straight back" - so that the spine is straightened but relaxed; the feet stand fully on the floor. Place the palm of one hand on your stomach. The thumb is at the level of the navel, and the other fingers are lower. Place the second hand behind, on the lower back, exactly opposite the palm lying on the stomach.

- Relax and breathe deeply in your stomach. Imagine a string stretched between the centers of both hands. Try to see it, feel it, describe it.

- Find the center of the string. Focus on it and take a few breaths and exhales. Pay attention to what images and feelings you have. Observe how there is a feeling of connection with the “belly brain” (the center of the abdomen, hara, dan-tyan). You will have a sense of centeredness, peace, relaxation and balance.

Neurocardiology and the brain in the heart

Just like the enteric nervous system, the heart’s complex circuitry allows it to act independently of the brain in the head – learning, remembering, and even feeling. A recent book, Basic and Clinical Neurocardiology, edited by Dr. Andrew Armour and Dr. Jeffrey Ardell, provides a comprehensive overview of the functions of the autonomic nervous system of the heart and the role of central and peripheral neurons in the regulation of cardiac function.

One of the pioneers of neurocardiology, Dr. Armour, shows that the heart has an internal nervous system complex enough to call it a separate “little brain.” The heart’s nervous system contains about 40,000 neurons called sensory axons. They capture circulating hormones and neurochemicals and track heart rate and blood pressure. Information about hormones, chemicals, heart rate and pressure is translated into neurological impulses by the heart’s nervous system and sent to the brain.

Thus, the heart has its own internal nervous system, acting and processing information independently of the brain or central nervous system. This is why the transplanted heart works. Normally, the heart communicates with the brain through tissues located along the vagus nerve and spinal column. In a transplanted heart, these nerve connections regenerate very slowly, if at all. However, a transplanted heart can function in a new home because it has its own holistic nervous system.

The reports of many heart transplant patients provide surprising evidence that the “heart brain” is capable of storing memories and influencing behavior. For example, Dr. Mario Alonso Pugh, a general practitioner (and abdominal surgery) surgeon, has been a leading surgeon at Harvard Medical School for more than twenty-five years and a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He reports one patient with a heart transplant. After the operation, the patient exhibited unusual behavior. He loved dishes he had never loved before. He became a fan of music he had never liked before. He was drawn to places he did not know or remember.

The mystery was revealed when doctors found out what kind of life was led by the donor, whose heart was transplanted to the patient. It turned out that the patient began to love the food that the donor preferred; in addition, the donor was a musician and played in a style that the patient suddenly loved, and the places in which the patient was drawn were iconic in the life of the donor. Due to strict privacy rules, neither the patient nor the doctors had access to the donor’s information or personal history. Perhaps somehow the donor's preferences were passed on to the patient along with his heart.

All these examples seem to confirm that the heart is a complex and mysterious organ, not just a blood pumping muscle.

Like the belly, the heart has always been considered an important center of knowledge and feeling. Some of the earliest known civilizations, including Ancient Greece, Mesopotamia, and Babylon, believed the heart to be the seat of intelligence. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote that the heart is the most important organ of the body and all nerves begin in it. Interestingly, according to his observations, this is the first organ that is formed in a chicken embryo. Aristotle believed that it is the center of intelligence, movement and sensation – the center of the vital force of the body.

Recently, various research groups are developing ways to penetrate the “brain” of the heart, especially the HeartMath Institute in Bouldercrick, California. Claiming that “the heart is the most powerful source of rhythmic informational images in the human body,” HeartMath researchers state: “As the most important interconnection center for many body systems, the heart is the single most powerful entry point into the network of communications connecting body, mind, emotion and spirit.”

HeartMath’s approach is based on the understanding that the heart interacts with the body and brain in four ways:

1. Neurologically – by transmitting nerve impulses through the vagus nerve and spine.

2. Biophysically - through the heartbeat. The heart sends energy in the form of blood pressure waves, also known as the pulse volume (BPV), which bring more or less concentration of blood supply to the cells of the body and brain. It was found that changes in the electrical activity of brain cells occur in accordance with changes in blood pressure waves.

3. Biochemically - through the release of neurotransmitters and hormonesFor example, such as atrial peptide, a hormone that slows the release of other stress hormones.

4. Energy-- through the electromagnetic fields generated by the heartbeat. An ECG used to measure the rhythm of the heartbeat, in particular, records the electrical signals emitted by the heart. These signals can not only be caught anywhere on the body, but also in the space around it.

HeartMath has developed a set of simple tools designed to help people connect with the intuitive intelligence of the heart brain and begin to gain support, expressed in the ability to better make decisions and use the wisdom of the heart to control the mind and emotions. A comprehensive study of these techniques, as well as their scientific basis, can be found in The HeartMath Solution (1999) by Doc Childre and Howard Martin. These tools have a lot in common with the main tools of NLP.

The simplest technique is called Freeze Frame. This is a one-minute procedure that can significantly change perception. It can be especially helpful in difficult or stressful situations. Below is a simple and brief summary of the sequence of actions:

1. Turn your attention from your thoughts to the area around your heart. Observe it for at least ten seconds while still breathing normally.

2. Think back to a positive experience or emotional state that you once experienced and relive it as fully as possible. See him, hear him and, most importantly, tune in to the sensory sensations in order to fully experience this state.

3. Ask your heart, “What can I do to change this situation?” or “What can I do to reduce stress?”

4. Listen to your heart’s response.

Even if you don’t hear anything, you’re likely to feel calmer and more relaxed. The answer can come not in words, but in the form of mental images or sensory sensation. You can get confirmation of something you already know, or you can look at it from a new, more harmonious perspective.

Cut-Thru is another HeartMath technique to help people better manage their emotions. Its goal is to help develop the ability to “release” complex long-standing emotional reactions, dynamically transform them and get out of dead ends.

1. Be aware of what you are feeling about a problem or situation by focusing on your heart.

2. Take an observer’s position on the situation. Act like it’s someone else’s problem. Think of yourself with third-person pronouns, i.e. “he” or “she” instead of “I” or “me.” What advice would you give yourself if you were a witness or mentor?

3. Imagine returning to your heart a distorted feeling or emotional energy that is in imbalance. Let it sink in there, as if you were plunging into a warm bath, so that it relaxes, blends and transforms. Practice trusting your heart to do the work for you.

The purpose of the release technique is to help people learn to accept, hold, and transform complex feelings instead of suppressing them.

The third tool, Heart Lock-In, helps you learn more about your heart in order to achieve physical, mental and spiritual recovery.

1. Shift your attention from your mind to your heart and let it stay there.

2. Remember the feeling of love, togetherness, or care that you feel easily toward someone. Focus on feeling grateful or grateful for someone or something positive. Practice being in this emotional state for five to fifteen minutes.

3. Take care to direct this feeling of love or appreciation to yourself and others.

This is not all that 3rd generation NLP calls the somatic mind. published

Author: Lyudmila Kolobovskaya

P.S. And remember, just changing our consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.b17.ru/blog/moi__psikholog__slovar_somatik_razum/

The scheme of purification of an organism by the method Agulova

These exercises relieve congestion in the pelvic organs