442

The effect of passing through the door: why we forget why we came

With all of us this has happened.

To go to take the keys but upon entering the bedroom, forget what you are looking for them. Open the refrigerator door and lean over the middle shelf only to realize that I can't remember why you opened the refrigerator. Or after waiting some time, to interrupt another, to find that the one burning question that forced us to intervene in the conversation, suddenly vanished from thought, once we started talking, "Hmm, what was I going to say?", you put your audience to a dead end, thinking to myself, "how do we know?!"

We can regard such moments of temporary loss of memory as something more than just an unfortunate misunderstanding. Although such errors can result in embarrassment, they are quite common.

They are known as "effect doors" ("Doorway Effect") and reveal some important quality of the organization of our mind.

Understanding this can help the perception of such moments of forgetfulness,as something more than just an annoying hindrance (although they will still be annoying).

These features of our minds, perhaps best illyustriruyuschie about a woman who met at lunchtime three builders.

"What are you doing today?", she asks them. — "I put a damn brick on the other," sighs the first. — "I'm building a wall", responds the second. — "I'm building a Cathedral," says filled with pride the third Builder.

Many have probably heard this story as motivating people to always think about larger picture. But the psychologist in you is important here also another conclusion — if you want to achieve in something success, it is about any action you need to think at different levels. Even if the look of the third Builder for my job and the most inspiring, nobody will be able to build a Cathedral, until you learn how to lay bricks and to do smooth walls.

During the day, our attention moves constantly between these levels —our goals and ambitions, plans and strategies, and to the lower levels — our concrete actions. When things are going well, often things are done by themselves, automatically and without our participation, and our attention is held at some other desired things. For example, if you are an experienced driver, you are driven with the gears, indicators and steering wheel automatically, and your attention is occupied, perhaps less routine tasks, like navigation or conversation with passengers. In the less routine things we have to shift our attention to detail that we do, going in my mind from the bigger picture for some time. Because of this, and pauses in conversation when the driver gets into a tricky intersection or the engine starts to make strange noises.

That is the image that our attention up and down the hierarchy, and allows us to implement complex behaviours, stitching together a coherent plan in many different moments, places and repeating the various actions.

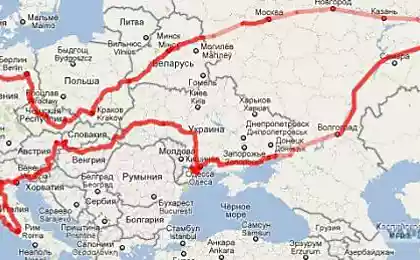

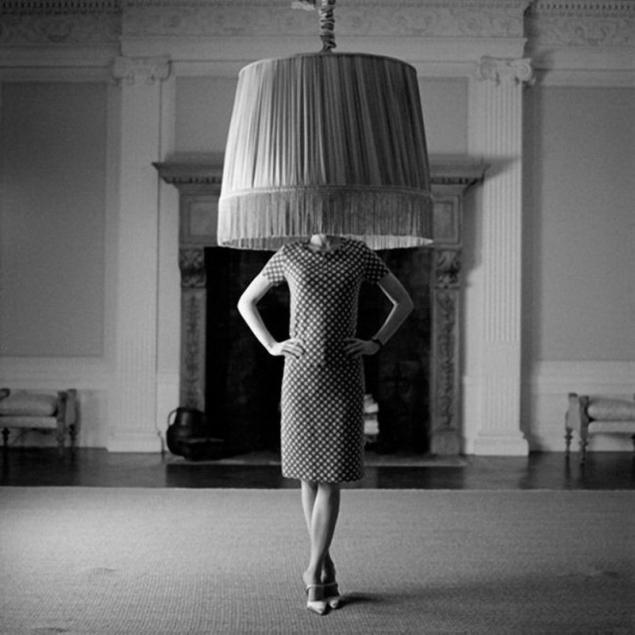

"Door effect" occurs when our attention moves between levels. And it reflects the dependence of our memory — even the memory that we're going to do from the environment in which we find ourselves.

Imagine that you climb the stairs to get my keys, and forget that you came here for the keys only enter a bedroom.

Psychologically, what happened is this plan ("Key!") belzabet right in the middle of the implementation of the necessary parts of this strategy ("Go to the bedroom!").

Perhaps this plan is part of a larger plan ("prepare to leave home!"), which is part of broader plans ("go to work!", etc). Each scale requires attention to a specific location. Somewhere while navigating this complex hierarchy in the brain the idea arose of having to get the keys. And like the torque plates on the poles of a circus acrobat, your attention focused on it long enough to make a plan, but then just moved on to the next plate (in this case, or on the way to the bedroom, or wondering who could again leave clothes on the stairs, or about what you will do after coming to work, or about a million other things of which life is built)

But sometimes the spinning plates fall. Our memory is even associated with our goals, embedded in a web of associations. This can be a natural environment in which we are forming them — hence a return to his childhood home can cause the flow of previously forgotten memories. Or it could be a mental environment — all those things that we thought, when something else intruded into those thoughts.

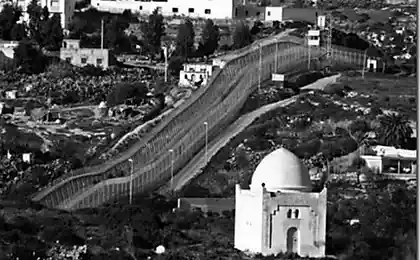

"Door effect" occurs when we change both the physical and mental environment, moving to another room and starting to think about other things. In haste arose in his mind the purpose, perhaps, is only one of the circus plates that we are trying to promote, forgotten along with the change of context. All this allowed the researchers to assume that the doorways act as a kind of psychological border, which "resets" our memories: "Passing through doorways serves as an event boundary, thus initiating the update event model [i.e. the creation of a new episode in memory]". Moreover, critical is the crossing of the threshold, not changing the environment. published

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: larkin-donkey.livejournal.com/203629.html

To go to take the keys but upon entering the bedroom, forget what you are looking for them. Open the refrigerator door and lean over the middle shelf only to realize that I can't remember why you opened the refrigerator. Or after waiting some time, to interrupt another, to find that the one burning question that forced us to intervene in the conversation, suddenly vanished from thought, once we started talking, "Hmm, what was I going to say?", you put your audience to a dead end, thinking to myself, "how do we know?!"

We can regard such moments of temporary loss of memory as something more than just an unfortunate misunderstanding. Although such errors can result in embarrassment, they are quite common.

They are known as "effect doors" ("Doorway Effect") and reveal some important quality of the organization of our mind.

Understanding this can help the perception of such moments of forgetfulness,as something more than just an annoying hindrance (although they will still be annoying).

These features of our minds, perhaps best illyustriruyuschie about a woman who met at lunchtime three builders.

"What are you doing today?", she asks them. — "I put a damn brick on the other," sighs the first. — "I'm building a wall", responds the second. — "I'm building a Cathedral," says filled with pride the third Builder.

Many have probably heard this story as motivating people to always think about larger picture. But the psychologist in you is important here also another conclusion — if you want to achieve in something success, it is about any action you need to think at different levels. Even if the look of the third Builder for my job and the most inspiring, nobody will be able to build a Cathedral, until you learn how to lay bricks and to do smooth walls.

During the day, our attention moves constantly between these levels —our goals and ambitions, plans and strategies, and to the lower levels — our concrete actions. When things are going well, often things are done by themselves, automatically and without our participation, and our attention is held at some other desired things. For example, if you are an experienced driver, you are driven with the gears, indicators and steering wheel automatically, and your attention is occupied, perhaps less routine tasks, like navigation or conversation with passengers. In the less routine things we have to shift our attention to detail that we do, going in my mind from the bigger picture for some time. Because of this, and pauses in conversation when the driver gets into a tricky intersection or the engine starts to make strange noises.

That is the image that our attention up and down the hierarchy, and allows us to implement complex behaviours, stitching together a coherent plan in many different moments, places and repeating the various actions.

"Door effect" occurs when our attention moves between levels. And it reflects the dependence of our memory — even the memory that we're going to do from the environment in which we find ourselves.

Imagine that you climb the stairs to get my keys, and forget that you came here for the keys only enter a bedroom.

Psychologically, what happened is this plan ("Key!") belzabet right in the middle of the implementation of the necessary parts of this strategy ("Go to the bedroom!").

Perhaps this plan is part of a larger plan ("prepare to leave home!"), which is part of broader plans ("go to work!", etc). Each scale requires attention to a specific location. Somewhere while navigating this complex hierarchy in the brain the idea arose of having to get the keys. And like the torque plates on the poles of a circus acrobat, your attention focused on it long enough to make a plan, but then just moved on to the next plate (in this case, or on the way to the bedroom, or wondering who could again leave clothes on the stairs, or about what you will do after coming to work, or about a million other things of which life is built)

But sometimes the spinning plates fall. Our memory is even associated with our goals, embedded in a web of associations. This can be a natural environment in which we are forming them — hence a return to his childhood home can cause the flow of previously forgotten memories. Or it could be a mental environment — all those things that we thought, when something else intruded into those thoughts.

"Door effect" occurs when we change both the physical and mental environment, moving to another room and starting to think about other things. In haste arose in his mind the purpose, perhaps, is only one of the circus plates that we are trying to promote, forgotten along with the change of context. All this allowed the researchers to assume that the doorways act as a kind of psychological border, which "resets" our memories: "Passing through doorways serves as an event boundary, thus initiating the update event model [i.e. the creation of a new episode in memory]". Moreover, critical is the crossing of the threshold, not changing the environment. published

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: larkin-donkey.livejournal.com/203629.html