537

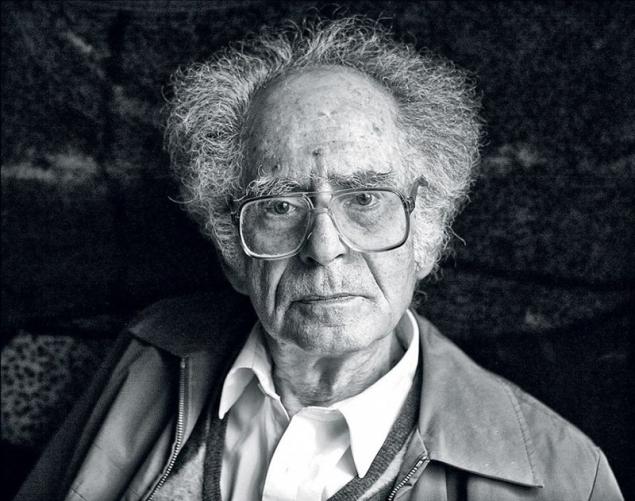

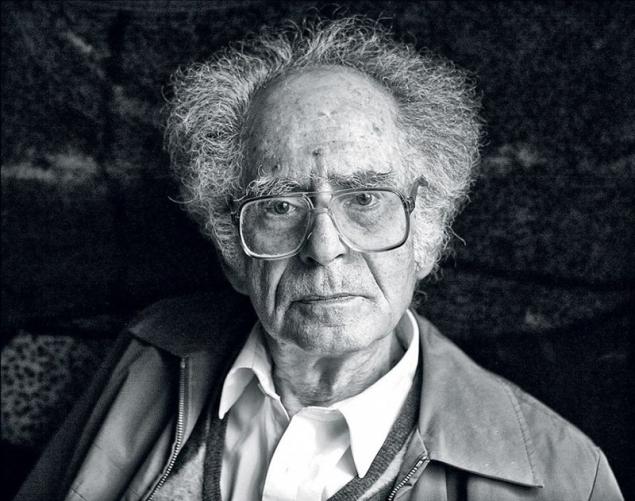

Gregory Pomerantz: the Soul that has come true

One of his articles, printed a blueprint on cigarette paper as was done then in Samizdat, I was able to read in Moscow. To follow seriously for his work was possible only after emigrating to America in 1981. I read the article Orange in émigré journals "Continent" and "Syntax," literally pounced on his collection of essays published in 1972 in Frankfurt. I remember the joy with which I bought Victor Kamkin — alas, long defunct — the number of "independent private", magazine "Russian Wealth", published intermittently since 1876. Now this room (No. 2, 1994), entirely dedicated to Grigory Pomerants, probably, rare.

It opens with the autobiographical novel "On the bird's rights".

Here is the first sentence explaining the meaning of the title: "I am a freelance Professor, essayist, writer in the social structure no one." In fact, the Orange somehow managed to survive half a century under the Soviet regime "the free artist"-a renegade, regardless of the conventional rigid Soviet norms. Was able, truthfully, to write only what he wanted.

He, of course, is everywhere denied, but the denials he treated philosophically: "... the Failure has ceased to humiliate me. And then it turned out that the failure — something like the waters of Styx that Thetis dipped her son. (Referring to the mother of Achilles, she dipped the son in the sacred water, holding the heel, his only vulnerable spot — the "Achilles heel" — A. M.) In this (inner spirit) all work and not in luck or bad luck".

It does not offend contemptuously stupid arrogance of Soviet officials. For example, he describes with humour how once she decided to get a place in Koktebel, in the house of creativity of writers, on the grounds that his wife was listed in groupname writers. That's only when applying it turned out that he forgot to bring a piece of paper about the condition. "We have writers (with the accent) bring a certificate from the attending physician!", — kicked him, referring to "real" writers, i.e., members of the Union of Soviet writers, and not some sort of Groupama. Looking from our time, we can safely say that mountains are "ideologically" writings of thousands of members of the SSP are not worth a single article of Orange.

In Russia it started to only print in the era of Perestroika, when the author was over 70 (!), although in many countries by that time, it has long been considered one of the greatest thinkers of our time.

It thinkers — prefer Pomerantz is a collective notion of the term "philosopher." Note that, in addition to philosophy, his writings touch on many of the other Humanities: history, cultural studies, Ethnography, sociology, linguistics, and theology. He wrote a lot about the poet-symbolists of the early twentieth century, whose symbol of faith was colorful, exotic, full of dangers, to live which was considered as important as succeeding in the work. In this sense, the biography of Orange is the envy of any symbolist, it is possible to create a fascinating novel or a feature film.

A life without fear

Here is just one episode from his life, which is just asking for the screen. Pomeranz was in the Gulag after the war, they traveled first a soldier, then officer, from Stalingrad to Berlin. The influx of new lag lead to the bath, where he encounters a bandit camp slang, "spun", which heads for snitching and physical strength made overseer in the quarantine barracks. His speech was full of gross obscenities, to which he himself was so accustomed to that I never expected to hear a polite request to stop swearing. And from someone from some puny intellectual by the name of Pomerantz, to say something which he would not turn around. Can you imagine the expression on his brutal face as he grabbed a stool to smash the insolent face. Besides, in the Nude, Grigory Solomonovich looked in front of him that skinny chick in front of mother bear. A few seconds spun held over the head a stool, and Grigory Solomonovich, not even trying to block the blow calmly looked him straight in the eye. This look urkagany not made — he tossed aside a stool and jumped out of the bath, deliberately hit the lintel.

Why didn't he kill Orange? Probably for the same reason Pushkin's Silvio in the story "the Shot" couldn't have killed Earl, the one during the duel calmly ate from the cap of cherries, spitting pits, and discovered no shadow of fear. The bandit may be the first time I saw the prisoner, absolutely not afraid.

And Pomeranz really did not know the feelings of fear, spared him in the war, in fierce bombardment of Stalingrad.

Nazi bombers "Heinkel" was flying, fortunately, at high altitude, it was not the case until caught in the open field, a lonely soldier, who managed to reach their trenches, but the bombs were falling around him without end with a heartbreaking whistle and roar. The young man, then twenty, trembled with fear, pleading: "Mom, save me!"

Suddenly he remembered the thought, for the first time, illuminating it for a few years before the war: "if the infinity is, by definition, the abyss, I'm not, but if I am, then there's abyss".

Thinking about this suddenly surfaced in mind is the metaphysical Maxim, he came to the conclusion that time he was not scared of the abyss of time and space, then there is nothing to fear and Heinkel. Self-hypnosis worked, and a few moments later he felt the fear disappears, goes away.And since that memorable day Gregory Pomerantz was not afraid of anyone or anything — as can be seen, the thinker, if it is true, the soul does not accept the humiliation of fear.

In the early thirties, writing school essay on a stencil theme "Who I want to be?" Gregory literally stunned the teacher of literature. Instead, strive to become a pilot, a Stakhanovite or polar, as it wished in himself to his classmates, he brought in a notebook: "I Want to be myself". Fortunately, he was not expelled for it from school, but certainly "took note", as they said. And he wrote the simple truth: why wish to be someone else the person realizes that God gave him remarkable talents and imagination. Once realizing this as early as school age, Gregory Pomerantz sought to develop their own individuality.

His articles gave me a lot of answers to the questions that occupied me for a long time. Here is one example.

We and I

When I was a correspondent for radio Moscow, I had the opportunity to speak at the round table with the participation of pre-selected honors students from the Soviet specialized schools "with teaching in English" and young Englishmen of the private schools, who came to Moscow as tourists. Mounting their performances for youth programs, I drew attention to the fact that the British almost every second sentence began with "I think", "my opinion", "personally, I believe", etc. At the same time, Soviet students at the start of any statement said: "we all believe", "we think" "our opinion."

The article "looking for freedom" Gregory Pomerantz says about "Soviet we", calling it "a Procrustean bed into which we had crammed". It was planted by the Soviet authorities the mentality of collectivism, which, according to him, "uprooting the root of the personal beginning, when "I am the last letter of the alphabet", any initiative is punishable, and all are equal in its impersonality". Speaking about his youth — and his essays and so strong that any philosophical thought he kind of skips through the filter of their own lives — Pomerantz writes:"the Intuitive sense of balance tells us that we cannot live with the consciousness of "we", "us", "we". That integrity sometimes requires emphasis on "I", my opinion on your non-standard act." The idea is seemingly simple, but there it was: the Orange all the ideas woven of contradictions: "Against Procrustean "we" I couldn't rebel and rested in contrast, in the empty gaps of the abstract "I" (separated from "we" and "I")".

It withdrew from the stalemate war. Like all soldiers, he dreamed about the victory, and then found what he calls "battlefield us". And in the Gulag our philosopher quite satisfied with the "we are anti-Soviet", found in the "Socratic" conversations with such as he, intelligent cons. On walks through the camp in their spare time, they discussed their General incompatibility with Soviet reality. And only after many years, surviving the death of the woman, and then again fell in love with his future wife, Grigory Solomonovich came to the conclusion that "there is some kind of I-Thou-We love (in the broadest sense of the word "love"), which is smarter, deeper each of us and merges with God's love. I feel "I", "You", "We" are not separate items, and different angles of the same Whole. "I" unique, inseparable from me, I am me, and at the same time, I yearn for its You, its We, until you find them, and finds himself in a dialogue with them..."

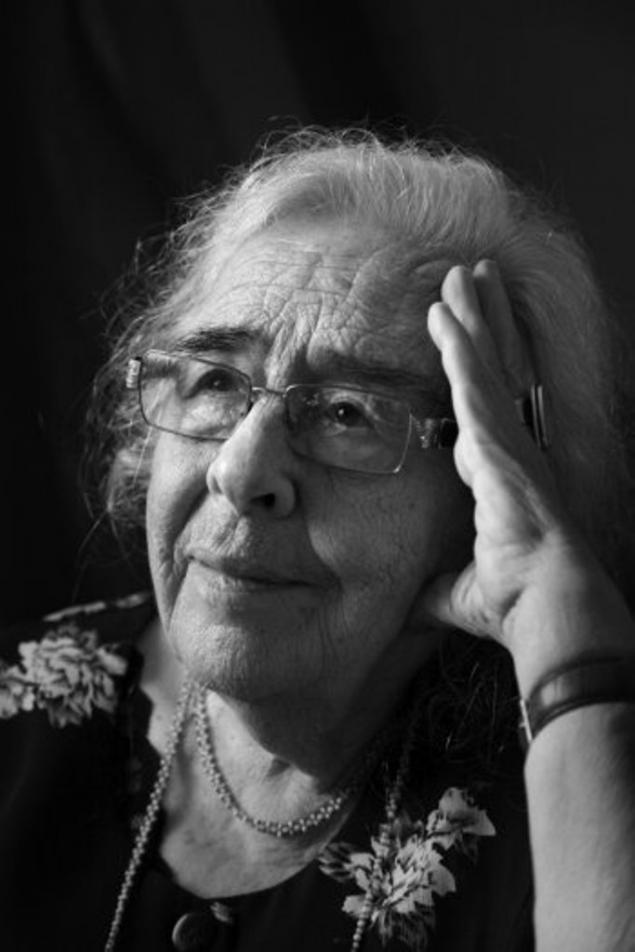

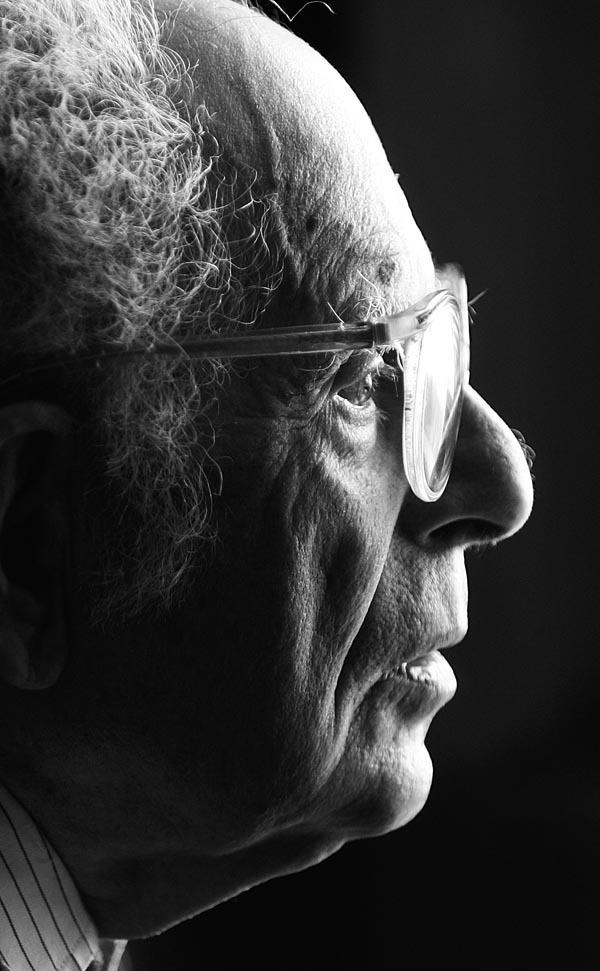

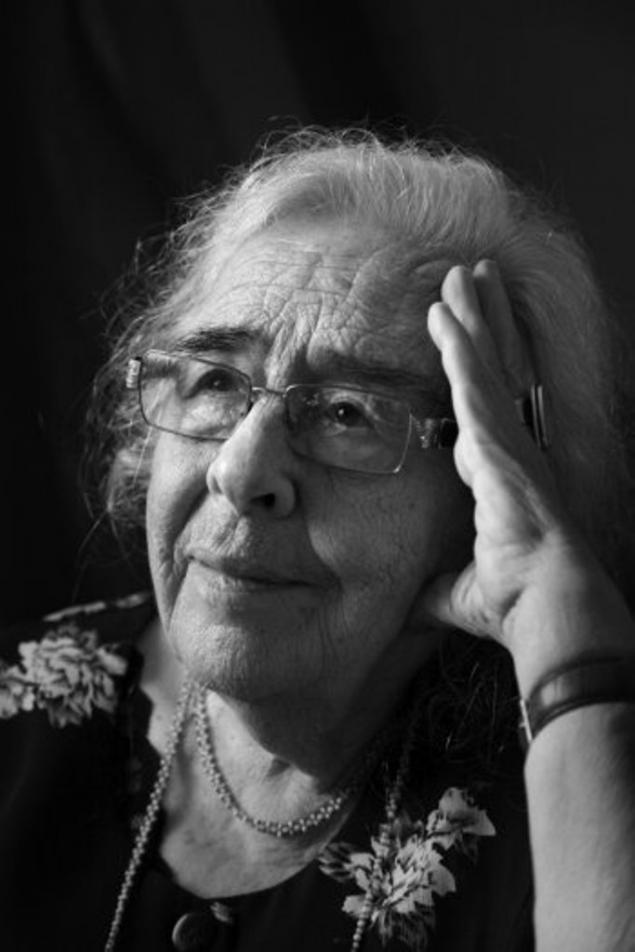

Wife Zinaida Mirkina

While a graduate student at new York University (NYU), I wrote an article on linguistics in which he drew attention to the fact, what was the impact of the Soviet mentality in the language. For example, I noted how the English language is "aggressive" in his grammar: in each sentence, with rare exceptions, easy to identify the figure performing the action. But Russian language is replete with impersonal phrases. You can say "sewed it up", or "he decided to settle accounts", or typically Soviet, "you do not understand", and who was killed, who killed, who does not understand — does not matter, that is, the worker is often not clear, which gives many statements of the sort of mystical character.

In other words, in the Russian language is more important than action, with you what is happening, rather than initiating his face. Incidentally, only in Russian can be quite natural to prevail Gogol's famous remark: "I am well today Vratsa" — in other European languages the word "to lie" as a reflexive, the intransitive verb is not used.

Confirmation and explanation of his thoughts I found in the article of Orange "In search of freedom". He also remembers there passive constructions in Russian, including the most mundane, such as "my name is", in contrast to the "I am", as is common in Western European languages, and examines this phenomenon in connection with the issue of human rights. Since the serfdom of the Russian peasants said: "we Pskov", "we Novgorod", as if to emphasize their belonging to the Pskov, Novgorod, etc., and a European or an American would say "I am Pskovityanka", or "I — Novgorodian". By analogy Pomeranz considers whether the most important word is "Russian". He writes: "the ethnonym "Russian" is an adjective, the designation of facilities of Russia. All other ethnonyms — contemptuous, swear — nouns. Only Russian defines themselves by membership of a great Empire, with humility and pride. Because the borders of the Empire can never be finally established, they spread indefinitely; almost as long as the Empire, capturing too much, not starts to fall apart".

Disinterested Gregory Pomerantz

In Russia men of genius acquired fame or after the early death or at the end of a long life. Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky, which I was lucky enough to interview, and spoke: "In Russia one should live long. Then something turns out."

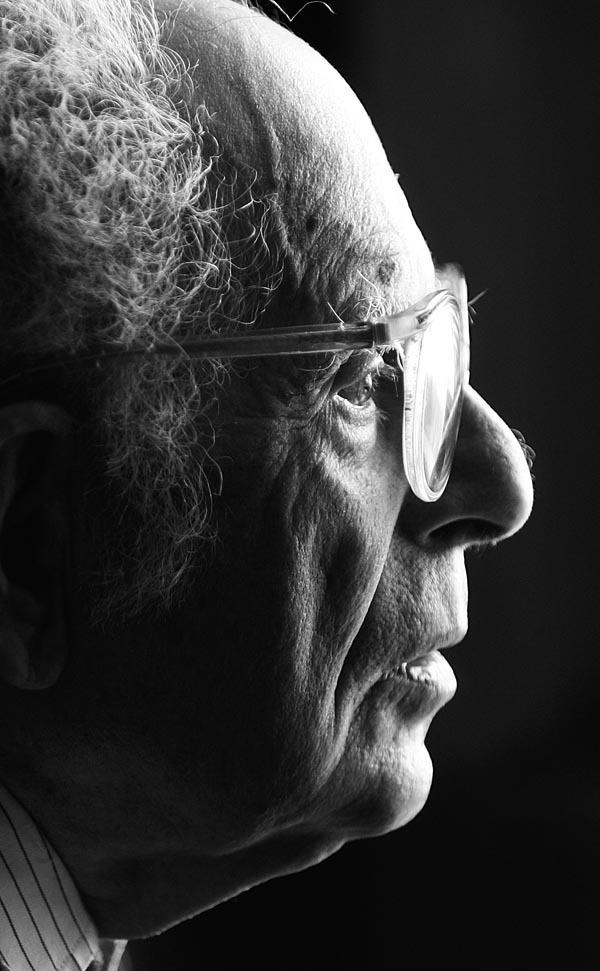

In 90-e years when Grigory Solomonovich finally began to release at the international conference, he visited many countries in Europe and Asia.And when he was 90 years old, he became famous and "in your homeland": it was a documentary film he was interviewed on television as a member of the Academy of humanitarian Sciences. At the same time, many Russians learned that one of them is not only a great mathematician and disinterested Perelman, but also the other Gregory, the great thinker Pomerantz, also a Jew, and too disinterested. After all, he who could easily become a Professor at any prestigious Western University, chose to stay in Russia, because there, in solitude, in contemplation of the nature managed to find himself. He's a stranger to honours and money. And enjoy nature, listen to music, read favorite poets, many poems of which he memorized, can be anywhere. I asked investegate, Larisa Miller, which connects with the family of Orange warm friendship, to share what primarily comes to her mind at the mention of the name of this thinker, and she said, "the Combination of passion and peace."

In old age — in March 2013, Grigory Solomonovich would have turned 95 years old — he wrote as brightly as in youth, and vividly expressed their history of beautiful language full of colorful metaphors and associations, without a single hitch. To verify this, view the television program about him and his wife on YouTube, as well as his "coffee room" in Google, where you'll find dozens of articles, and many of them have been written in the last five to ten years.

Happiness is an Orange

These articles affectdramatically for all of us concepts: love, faith, freedom, happiness. Will focus on the latter, because probably there is no person who would not aspire to happiness, this aspiration is even enshrined in the Declaration of independence. The article "a Genuine and illusory happiness" Pomeranz leads the most interesting statements of philosophers, writers and poets about this feeling. He considers the happiness of the examples of famous literary heroes, celebrates the various hues of happiness at one and the same character, in particular, Goethe's Faust. In the same way as in the article about freedom, Pomerantz appeals to linguistics in search of a deeper meaning inherent in the word: "happiness, the Assembly of all parts, the integrity of life. In contrast, u-part, setisodate in some part of life, as in the dungeon". But perhaps the most interesting in this article is his personal happiness. According to his testimony, he sometimes felt this way in case of emergency:

"The most common of all cases of happiness that I experienced — it appears to be the creative state. It first came to me in twelve years for course work about Dostoevsky. (Later Pomeranz devoted to the work of a favorite writer's book "the Openness of the abyss" and many articles by A. M).

It is, in my opinion, came at the front like the feeling of flying over the fear. For the most part, a striking clarity of thought associated with the feeling of such a flight, not in a foreign language, but once I have a few hours led the fight and did it sensibly, although it was not studied tactics. I think that can be called creative as and love... Without inspiration, without the creative state music love not write, not write a Symphony".

In another autobiographical article Pomerantz sums up the same thought differently: "Happiness is not a wallet on the road. It is opened from the inside, and that it was opened, it was all the past, all the failures, which were true soul."

Unfortunately, most people do not experience genuine happiness, and a Ghost, soon transient, not well-deserved, in other words, — find the same "wallet on the road." It can be ecstasy caused by drugs, alcohol, sex, such "accidental flash, leaving only a longing for new outbreaks". And what we call the "sweet life" turns into an illusion that kills the possibility of real happiness. Summarizing these thoughts, Pomerantz brings the postulates, sounding like farewell readers. Here are some of them:

"The happiness of creativity — in the creative work, even without recognition, without success. Happiness of love is love itself, even without reciprocity. The ability to do so is part of the secrets exchanged between lovers. Happiness is love, happiness, creativity, victory over obstacles is not high, and the path through pain and labor, as the happiness of the mother."

It is very difficult in a few words describe the main themes of the multi-faceted creative heritage of Orange. To some extent it managed to academician Andrei Sakharov. In his memoirs, speaking of the dissident seminar gathered at the apartment of physicist Valentin Turchin in the 70-ies, he notes:

"The most interesting and profound reports were Grigory Pomeranz – I first learned it then, and was deeply impressed by his erudition, breadth of views and "academic" in the best sense of the word. The basic concept of Orange: the exceptional value of culture created by the interaction of the efforts of all the Nations of the East and West for millennia, the need for tolerance, compromise and breadth of thought, the poverty and wretchedness of dictatorship and totalitarianism, their historical futility, wretchedness and the futility of narrow nationalism footing".

Read any article Orange, and you will realize how masterfully and creatively at the same time freely and acutely in a timely manner it is written. You will feel emanating from it, the good, the desire to aid readers in understanding the core values. Most valuable for this deeply religious man was a living human soul. In one of his works, he called a talented photographer "anti-Chichikov" in the sense that he sought to catch are not dead, but living souls.

This "catcher living souls" seems to me, and he Grigory Pomeranz. He died 16 Feb 2013, before reaching one month to 95 years, all the conscious part of which was spent in selfless service to people.published

Author: Azary Messerer

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: www.chayka.org/node/5329

It opens with the autobiographical novel "On the bird's rights".

Here is the first sentence explaining the meaning of the title: "I am a freelance Professor, essayist, writer in the social structure no one." In fact, the Orange somehow managed to survive half a century under the Soviet regime "the free artist"-a renegade, regardless of the conventional rigid Soviet norms. Was able, truthfully, to write only what he wanted.

He, of course, is everywhere denied, but the denials he treated philosophically: "... the Failure has ceased to humiliate me. And then it turned out that the failure — something like the waters of Styx that Thetis dipped her son. (Referring to the mother of Achilles, she dipped the son in the sacred water, holding the heel, his only vulnerable spot — the "Achilles heel" — A. M.) In this (inner spirit) all work and not in luck or bad luck".

It does not offend contemptuously stupid arrogance of Soviet officials. For example, he describes with humour how once she decided to get a place in Koktebel, in the house of creativity of writers, on the grounds that his wife was listed in groupname writers. That's only when applying it turned out that he forgot to bring a piece of paper about the condition. "We have writers (with the accent) bring a certificate from the attending physician!", — kicked him, referring to "real" writers, i.e., members of the Union of Soviet writers, and not some sort of Groupama. Looking from our time, we can safely say that mountains are "ideologically" writings of thousands of members of the SSP are not worth a single article of Orange.

In Russia it started to only print in the era of Perestroika, when the author was over 70 (!), although in many countries by that time, it has long been considered one of the greatest thinkers of our time.

It thinkers — prefer Pomerantz is a collective notion of the term "philosopher." Note that, in addition to philosophy, his writings touch on many of the other Humanities: history, cultural studies, Ethnography, sociology, linguistics, and theology. He wrote a lot about the poet-symbolists of the early twentieth century, whose symbol of faith was colorful, exotic, full of dangers, to live which was considered as important as succeeding in the work. In this sense, the biography of Orange is the envy of any symbolist, it is possible to create a fascinating novel or a feature film.

A life without fear

Here is just one episode from his life, which is just asking for the screen. Pomeranz was in the Gulag after the war, they traveled first a soldier, then officer, from Stalingrad to Berlin. The influx of new lag lead to the bath, where he encounters a bandit camp slang, "spun", which heads for snitching and physical strength made overseer in the quarantine barracks. His speech was full of gross obscenities, to which he himself was so accustomed to that I never expected to hear a polite request to stop swearing. And from someone from some puny intellectual by the name of Pomerantz, to say something which he would not turn around. Can you imagine the expression on his brutal face as he grabbed a stool to smash the insolent face. Besides, in the Nude, Grigory Solomonovich looked in front of him that skinny chick in front of mother bear. A few seconds spun held over the head a stool, and Grigory Solomonovich, not even trying to block the blow calmly looked him straight in the eye. This look urkagany not made — he tossed aside a stool and jumped out of the bath, deliberately hit the lintel.

Why didn't he kill Orange? Probably for the same reason Pushkin's Silvio in the story "the Shot" couldn't have killed Earl, the one during the duel calmly ate from the cap of cherries, spitting pits, and discovered no shadow of fear. The bandit may be the first time I saw the prisoner, absolutely not afraid.

And Pomeranz really did not know the feelings of fear, spared him in the war, in fierce bombardment of Stalingrad.

Nazi bombers "Heinkel" was flying, fortunately, at high altitude, it was not the case until caught in the open field, a lonely soldier, who managed to reach their trenches, but the bombs were falling around him without end with a heartbreaking whistle and roar. The young man, then twenty, trembled with fear, pleading: "Mom, save me!"

Suddenly he remembered the thought, for the first time, illuminating it for a few years before the war: "if the infinity is, by definition, the abyss, I'm not, but if I am, then there's abyss".

Thinking about this suddenly surfaced in mind is the metaphysical Maxim, he came to the conclusion that time he was not scared of the abyss of time and space, then there is nothing to fear and Heinkel. Self-hypnosis worked, and a few moments later he felt the fear disappears, goes away.And since that memorable day Gregory Pomerantz was not afraid of anyone or anything — as can be seen, the thinker, if it is true, the soul does not accept the humiliation of fear.

In the early thirties, writing school essay on a stencil theme "Who I want to be?" Gregory literally stunned the teacher of literature. Instead, strive to become a pilot, a Stakhanovite or polar, as it wished in himself to his classmates, he brought in a notebook: "I Want to be myself". Fortunately, he was not expelled for it from school, but certainly "took note", as they said. And he wrote the simple truth: why wish to be someone else the person realizes that God gave him remarkable talents and imagination. Once realizing this as early as school age, Gregory Pomerantz sought to develop their own individuality.

His articles gave me a lot of answers to the questions that occupied me for a long time. Here is one example.

We and I

When I was a correspondent for radio Moscow, I had the opportunity to speak at the round table with the participation of pre-selected honors students from the Soviet specialized schools "with teaching in English" and young Englishmen of the private schools, who came to Moscow as tourists. Mounting their performances for youth programs, I drew attention to the fact that the British almost every second sentence began with "I think", "my opinion", "personally, I believe", etc. At the same time, Soviet students at the start of any statement said: "we all believe", "we think" "our opinion."

The article "looking for freedom" Gregory Pomerantz says about "Soviet we", calling it "a Procrustean bed into which we had crammed". It was planted by the Soviet authorities the mentality of collectivism, which, according to him, "uprooting the root of the personal beginning, when "I am the last letter of the alphabet", any initiative is punishable, and all are equal in its impersonality". Speaking about his youth — and his essays and so strong that any philosophical thought he kind of skips through the filter of their own lives — Pomerantz writes:"the Intuitive sense of balance tells us that we cannot live with the consciousness of "we", "us", "we". That integrity sometimes requires emphasis on "I", my opinion on your non-standard act." The idea is seemingly simple, but there it was: the Orange all the ideas woven of contradictions: "Against Procrustean "we" I couldn't rebel and rested in contrast, in the empty gaps of the abstract "I" (separated from "we" and "I")".

It withdrew from the stalemate war. Like all soldiers, he dreamed about the victory, and then found what he calls "battlefield us". And in the Gulag our philosopher quite satisfied with the "we are anti-Soviet", found in the "Socratic" conversations with such as he, intelligent cons. On walks through the camp in their spare time, they discussed their General incompatibility with Soviet reality. And only after many years, surviving the death of the woman, and then again fell in love with his future wife, Grigory Solomonovich came to the conclusion that "there is some kind of I-Thou-We love (in the broadest sense of the word "love"), which is smarter, deeper each of us and merges with God's love. I feel "I", "You", "We" are not separate items, and different angles of the same Whole. "I" unique, inseparable from me, I am me, and at the same time, I yearn for its You, its We, until you find them, and finds himself in a dialogue with them..."

Wife Zinaida Mirkina

While a graduate student at new York University (NYU), I wrote an article on linguistics in which he drew attention to the fact, what was the impact of the Soviet mentality in the language. For example, I noted how the English language is "aggressive" in his grammar: in each sentence, with rare exceptions, easy to identify the figure performing the action. But Russian language is replete with impersonal phrases. You can say "sewed it up", or "he decided to settle accounts", or typically Soviet, "you do not understand", and who was killed, who killed, who does not understand — does not matter, that is, the worker is often not clear, which gives many statements of the sort of mystical character.

In other words, in the Russian language is more important than action, with you what is happening, rather than initiating his face. Incidentally, only in Russian can be quite natural to prevail Gogol's famous remark: "I am well today Vratsa" — in other European languages the word "to lie" as a reflexive, the intransitive verb is not used.

Confirmation and explanation of his thoughts I found in the article of Orange "In search of freedom". He also remembers there passive constructions in Russian, including the most mundane, such as "my name is", in contrast to the "I am", as is common in Western European languages, and examines this phenomenon in connection with the issue of human rights. Since the serfdom of the Russian peasants said: "we Pskov", "we Novgorod", as if to emphasize their belonging to the Pskov, Novgorod, etc., and a European or an American would say "I am Pskovityanka", or "I — Novgorodian". By analogy Pomeranz considers whether the most important word is "Russian". He writes: "the ethnonym "Russian" is an adjective, the designation of facilities of Russia. All other ethnonyms — contemptuous, swear — nouns. Only Russian defines themselves by membership of a great Empire, with humility and pride. Because the borders of the Empire can never be finally established, they spread indefinitely; almost as long as the Empire, capturing too much, not starts to fall apart".

Disinterested Gregory Pomerantz

In Russia men of genius acquired fame or after the early death or at the end of a long life. Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky, which I was lucky enough to interview, and spoke: "In Russia one should live long. Then something turns out."

In 90-e years when Grigory Solomonovich finally began to release at the international conference, he visited many countries in Europe and Asia.And when he was 90 years old, he became famous and "in your homeland": it was a documentary film he was interviewed on television as a member of the Academy of humanitarian Sciences. At the same time, many Russians learned that one of them is not only a great mathematician and disinterested Perelman, but also the other Gregory, the great thinker Pomerantz, also a Jew, and too disinterested. After all, he who could easily become a Professor at any prestigious Western University, chose to stay in Russia, because there, in solitude, in contemplation of the nature managed to find himself. He's a stranger to honours and money. And enjoy nature, listen to music, read favorite poets, many poems of which he memorized, can be anywhere. I asked investegate, Larisa Miller, which connects with the family of Orange warm friendship, to share what primarily comes to her mind at the mention of the name of this thinker, and she said, "the Combination of passion and peace."

In old age — in March 2013, Grigory Solomonovich would have turned 95 years old — he wrote as brightly as in youth, and vividly expressed their history of beautiful language full of colorful metaphors and associations, without a single hitch. To verify this, view the television program about him and his wife on YouTube, as well as his "coffee room" in Google, where you'll find dozens of articles, and many of them have been written in the last five to ten years.

Happiness is an Orange

These articles affectdramatically for all of us concepts: love, faith, freedom, happiness. Will focus on the latter, because probably there is no person who would not aspire to happiness, this aspiration is even enshrined in the Declaration of independence. The article "a Genuine and illusory happiness" Pomeranz leads the most interesting statements of philosophers, writers and poets about this feeling. He considers the happiness of the examples of famous literary heroes, celebrates the various hues of happiness at one and the same character, in particular, Goethe's Faust. In the same way as in the article about freedom, Pomerantz appeals to linguistics in search of a deeper meaning inherent in the word: "happiness, the Assembly of all parts, the integrity of life. In contrast, u-part, setisodate in some part of life, as in the dungeon". But perhaps the most interesting in this article is his personal happiness. According to his testimony, he sometimes felt this way in case of emergency:

"The most common of all cases of happiness that I experienced — it appears to be the creative state. It first came to me in twelve years for course work about Dostoevsky. (Later Pomeranz devoted to the work of a favorite writer's book "the Openness of the abyss" and many articles by A. M).

It is, in my opinion, came at the front like the feeling of flying over the fear. For the most part, a striking clarity of thought associated with the feeling of such a flight, not in a foreign language, but once I have a few hours led the fight and did it sensibly, although it was not studied tactics. I think that can be called creative as and love... Without inspiration, without the creative state music love not write, not write a Symphony".

In another autobiographical article Pomerantz sums up the same thought differently: "Happiness is not a wallet on the road. It is opened from the inside, and that it was opened, it was all the past, all the failures, which were true soul."

Unfortunately, most people do not experience genuine happiness, and a Ghost, soon transient, not well-deserved, in other words, — find the same "wallet on the road." It can be ecstasy caused by drugs, alcohol, sex, such "accidental flash, leaving only a longing for new outbreaks". And what we call the "sweet life" turns into an illusion that kills the possibility of real happiness. Summarizing these thoughts, Pomerantz brings the postulates, sounding like farewell readers. Here are some of them:

"The happiness of creativity — in the creative work, even without recognition, without success. Happiness of love is love itself, even without reciprocity. The ability to do so is part of the secrets exchanged between lovers. Happiness is love, happiness, creativity, victory over obstacles is not high, and the path through pain and labor, as the happiness of the mother."

It is very difficult in a few words describe the main themes of the multi-faceted creative heritage of Orange. To some extent it managed to academician Andrei Sakharov. In his memoirs, speaking of the dissident seminar gathered at the apartment of physicist Valentin Turchin in the 70-ies, he notes:

"The most interesting and profound reports were Grigory Pomeranz – I first learned it then, and was deeply impressed by his erudition, breadth of views and "academic" in the best sense of the word. The basic concept of Orange: the exceptional value of culture created by the interaction of the efforts of all the Nations of the East and West for millennia, the need for tolerance, compromise and breadth of thought, the poverty and wretchedness of dictatorship and totalitarianism, their historical futility, wretchedness and the futility of narrow nationalism footing".

Read any article Orange, and you will realize how masterfully and creatively at the same time freely and acutely in a timely manner it is written. You will feel emanating from it, the good, the desire to aid readers in understanding the core values. Most valuable for this deeply religious man was a living human soul. In one of his works, he called a talented photographer "anti-Chichikov" in the sense that he sought to catch are not dead, but living souls.

This "catcher living souls" seems to me, and he Grigory Pomeranz. He died 16 Feb 2013, before reaching one month to 95 years, all the conscious part of which was spent in selfless service to people.published

Author: Azary Messerer

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: www.chayka.org/node/5329