737

The eternal present: Kirill Kobrin of Baudelaire, Marx and revolution

Thirty two million eight hundred seventy three thousand six hundred eighty

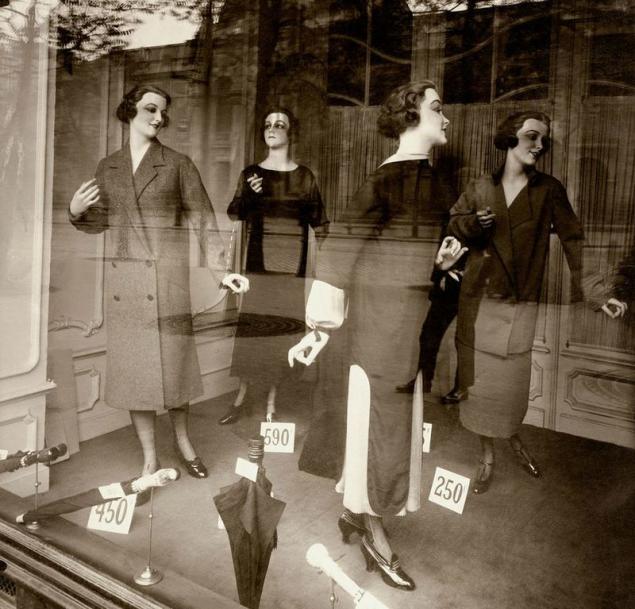

© Eugene Atget

Understanding of class struggle by Karl Marx intersects with the notion of modernité (modernity, modernity), which is one of the first comprehended Charles Baudelaire. The coming revolution is not focused on gradual improvement (progress), but, paradoxically, must break with modernity, embodied in itself is. T&P publishes an excerpt from a new book by historian and essayist Kirill Kobrin "Modernitè in selected stories", published by the HSE.

In 1864 in London, in the concert hall of St. Martins Hall in Covent garden, was created by the First international (International Association of workers); in the constituent Assembly was attended by Karl Marx, who was elected to the leadership of the new organization. He also asked to write the inaugural address and provisional rules of the Association. One hundred years later, in 1964, Isaiah Berlin's essay "Marxism and the international in the nineteenth century" gave a compact, surprisingly clear presentation of the theory of Marx and its subsequent adventures; the author timed his text for the centennial of the First International Association of workers. Twelve years before the founding meeting of the First international in St. Martins Hall, Karl Marx publishes in the German-language journal Die Revolution, which was published in the US immigrant Joseph Weydemeyer, a great political pamphlet "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte", where in hot pursuit analyzes the developments in France from the February revolution of 1848 to the establishment of the Second Empire. Marx wrote his work at a time when new prospects (called "Bonapartist") regime was very vague; the author's conclusions were accurate, and it is allowed to republish the work when the life of Marx in 1869-m, a year before the collapse of the regime of Napoleon III.

In the Preface to the first reprint Marx writes that practically did not change the text seventeen years ago; he thereby hints: it contained a new approach to political analysis is much more important than the political turnover because, for example, can not explain the German reader 1869 French personalities 1849. In other words, we have before us a theoretical essay, one of the cornerstones of the building of the theory of class struggle and the proletarian revolution; moreover, the "Eighteenth Brumaire" — I think the first essay of Marx, where he methodically and deliberately used only the created concept to the important political events of the time strongly influenced all of Europe. And although in the Preface to the first reprint Marx argues that undertook this work out of a desire to help colleague, started a radical political weekly, however, as often happens, the temptation to use the latest vseobyasnyayuschego revolutionary concept for the explanation of the freshest of the revolution on a European scale (not to mention the fact that by the beginning of 1852 many other European countries raging there revolution has only just calmed down or been suppressed) overcame a casual, almost "customized" nature of the work. Masterpieces not necessarily born from the intention to create such, slowly working in quiet offices, after diligent preliminary work and solitary walks through the countryside. Often, if the author's idea is already "ready" to work, and on the horizon looms no office, no free time, nor even the path in the middle of a peaceful green pastures — everything is different, and from the nature of the light of God is the uncorrupted value (or apparent as such). Apparently, the same thing happened with "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte", which, of course, there's a kind of masterpiece of political thought and ideological calculation.

Moreover, in the third, posthumous German edition of the pamphlet, 1889-m (remember, that year was established the Second international) "the Eighteenth Brumaire" is called Engels "brilliant", after which his Preface is followed by this passage:

"It marks the first time discovered a great law of motion of history, the law according to which every historical struggle — whether it takes place in the political, religious, philosophical or any other ideological sphere is in reality only a more or less clear expression of the struggle of social classes, and the existence of these classes and at the same time their collisions among themselves in turn determined by the degree of development of their economic status, the nature and mode of production and defined by the exchange. This law, which was Central to the story is the same value as the law of transformation of energy for science, was to Marx and in this case, the key to understanding the history of the French Second Republic. In this story he is in this paper tested the validity of the open of the law, and even thirty-three years later still it should be recognized that this test gave excellent results."

So, if the first German re-release has been started, to remind the reader — and it was already the reader is quite different than in 1852, in front of us the audience of the First international — the fundamentals of the theory of the class struggle, the second is already triumphantly showed the social-democratic Second international audience not only theoretical, but practical and political correctness of Marx. Second Empire ignominiously collapsed, revealing its rotten to the core, about which so much is said in the "Eighteenth Brumaire", the Paris bourgeoisie has made another revolution, again, exactly according to Marx, exposing the weakness of her, followed by the Paris Commune — that is, Marx predicted social revolution, proletarian (here it does not matter that the original theorist was regarded practices-the Communards pretty cool and disbelief).As you can see, closely are related to two of the revolution (1848-1849 and 1870-1871), two international (First and Second) and two pieces about the same size: "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" Karl Marx and "Marxism and the international in the nineteenth century," Isaiah Berlin. At the intersection of these events and texts, I will try to build your own text. The main object of analysis will be the "Eighteenth Brumaire"; essays of Berlin (in itself wonderful!) there is here almost invisibly and it is mentioned only in a few places. Finally, I drew another material, which neither Marx nor the Berlin stories related to public, cultural and ideological history of the Second Empire. Chief among them is the notion of modernity, modernité appeared (due to the efforts of Charles Baudelaire) in those years and in Paris.

As is well known, Walter Benjamin first brought together Marx and Baudelaire in the analysis of this plot; since then the writings on the cultural history and the history of ideas, this combination has become almost classic; but despite the attention to the topic, today one can hardly speak about her exhaustion. In particular, fundamentally important is the question of our own position on this key period in the history of the West, when Paris was, in the words of Benjamin, the "capital of the nineteenth century." Where is today's Western consciousness outside or inside of that period, the determination (and even the content itself) which was minted between the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte and judgment of "Madame Bovary"? Currently, the most common answer to this question is negative, they say, present in the past, we have been in the post-stage; well, let's see if we can put this answer into question.[...]

Class struggle vs. stuffy clubs perfume

The most interesting topic today "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" is associated with the ratio of stories, "repeated twice" (the famous opening sentence of the pamphlet), and the revolutionary interpretation of history, which comes from the unheard-of principle of the class struggle. Early revolution (from the first half of the XVI century — if you count the Reformation as a "revolution", as did Marx and Engels — until the second half of the eighteenth century) to dress in clothing of the past to prove its relevance, correctness, to legitimize themselves. New things come in old clothes, all patterns, images and rhetorical figures set old time. There are two poles of Antiquity and the old Testament. The first model — for social revolutions, the second for the reformation and subsequent Protestant movements; that is to say, Athens and Jerusalem, the dual scheme, which, as we know, Lev Shestov, exhausts European tradition. At the same time conservatism, any conservatism, "counter-revolution" is preferred as the material for its ideological constructs are quite different historical periods, as well as non-European culture — the New Testament instead of the old, the Middle ages instead of classical Antiquity, Oriental despotism and China instead of Athens and Rome. But after 1815 th there is a major modification: radical movements and revolutions deliberately imitate the great French revolution (and some of the War for independence of North American colonies). There is already a very different, consciously "modern" type of historical legitimation of opposing the enforcement. After 1815, the progressives and radicals, as before, look back, however, they deliberately short-sighted and then Robespierre (or, a little later for Europe and as another option, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington) don't see anything suitable.

Modernity becomes the source and the result of itself; at the same time she often despises it, hoping to get rid of any past.For Marx, this "myopia" for the incarnation is not authentic; the way out is not authentic, a breakthrough to the truth he sees not a return to the retrospective "hyperopia", and focus exclusively on the present. As a tool of analysis, the only true interpretation of the mechanism he proposes the concept of class struggle, rooted in the past (the past can — and should — be subject to the application of this concept, but in the past it was not). New is read using the new — in this sense Karl Marx, along with Charles Baudelaire, perhaps the main Creator of the concept of modernity, produced from material of our time. Modernity becomes the source and the result of itself; at the same time, as we see in Marx, she often despises it, hoping to get rid of any past.

Roberto Calasso notes:

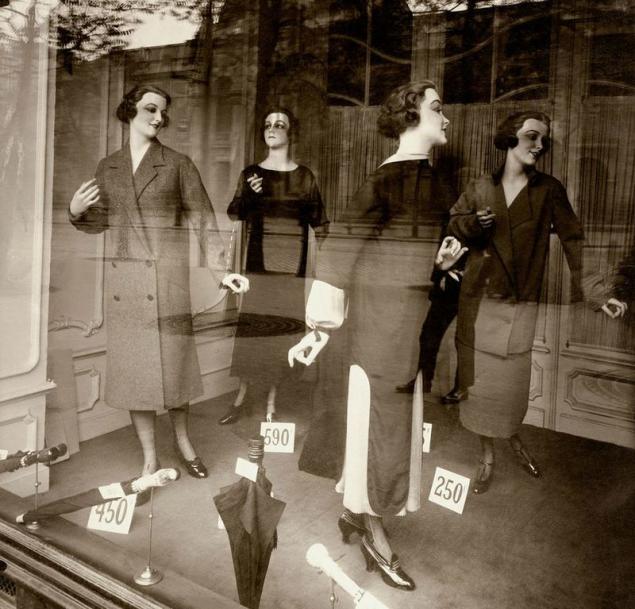

"The word vulgarité introduced by Madame de Stael in 1800. Modernité we meet in théophile Gautier's 1852-m. But in the "Sepulchral notes" Chateaubriand, published in 1849, these two words stand side by side in the same phrase that describes problems the author has encountered Wurttemberg customs: "the Vulgarity, the modernity of customs and passports". If fate had appointed these two to be together. That was before? Was a vulgar person, but was not vulgar. And were modern people, but it was not present. (...) Modernity: the word that appears and runs between Gautier and Baudelaire in the Second Empire, in a period of just over ten years, between 1852 and 1863. And every time it is presented gently, with the understanding that the present their language to a foreigner. Gautier (1855): "Modernity. Is there such a noun? The feeling which it expresses, is so recent that this word is likely not in the dictionary". Baudelaire (1863): "He's looking for something that we are allowed to call modernity, insofar as there is no better word that expresses this idea." But that was the idea, so fresh and implicit, to Express which there was not yet refer to? From what has been made modernity? Evil Jean Rousseau then declared that modernity consists of women's bodies and trinkets. Arthur Stevens, defending Baudelaire, first called the poet a man, "which, I think, invented the word, modernity." Through painting and frivolity this word into the dictionary. And it was doomed to gain a foothold there, growing, conquering and devastating — new areas. Soon no one remembered his modestly-frivolous beginning. From Baudelaire, however, the word remained in the clubs of powder and perfume".

Pay attention to two things. First: modernité appears along with the Second Empire, perfectly coinciding in time with the development of a Mature Marxist theory. Where Gauthier sly kick sends the ball in the modern field of Baudelaire, and is the final point "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" by Karl Marx. Second, for Baudelaire that was forged out of this concept, modernity of art — and in this case it writes about art is when its object shall be elected not "sanctified vegetables" plein air, brothels, parks, dancing halls and avenues, that is what exists now and in its current form relatively recently appeared in the city life. The very contemporary city, with its vices, obscenity, accessible to women, shrouded in stifling clouds of perfume, is the embodiment of modernité. Similarly, Marx believed the true revolution is only the one that thinks itself a part of modernity and not disguises itself in "consecrated by antiquity."

The revolution is afraid of its novelty, its modernity, is afraid of himself as a "revolution."Modernity is ambivalent: she is trying to build their genealogy to its own past and simultaneously denies the need for genealogy as such. Artistic vanguard of the XX century in its beginning is even more exposed this duality: dropping from the ship of modernity past, he simultaneously attempts to find predecessors, and in the most random and illogical, it would seem, of contexts, beyond the mechanism of "myopia." Modernity doesn't trust the past, even his own, but to be in a situation of "pure this" or even "clean future" is afraid. Hence the attempts, for instance, of the Surrealists to make a list of their own great — totally random — predecessors. It ends not with a Bang but a damning irony in Borges's essay "Kafka and his precursors", and his imaginary literary and philosophical pedigrees. The fight against the "nightmare of the traditions of past generations" through his denial and attempt to establish power over him through an arbitrary point of the choice of their predecessors ends complete mystification of the past, the final deprivation of any meaning except decorative (as in the same of Borges, and in the worst case, as his epigones type of Milorad pavić).

The prison of modernity

Moving on to the next question: why the revolution, the main (along with progress) invention of modernity, this old outfit? Marx's answer is: from time to time revolution is ashamed (or afraid) of its true content, attempting to offer to yourself and others something more "noble" and "legitimate" (which means — rooted in history, in "the traditions of past generations"). In other words, the revolution is afraid of its novelty, its modernity, is afraid of himself as a "revolution." The first revolution of turning to Ancient Greece and Rome, but later — in fact, to the first two revolutions. That is why so very important War for US independence and the French revolution. But then the following question arises. Why Marx believes that in the mid-nineteenth century, such thinking is shameful and napolino? The answer is simple: changed the very content of the revolution. The bourgeois political revolution is transformed into social (with the prospect of a purely proletarian). After the proletarian nothing will happen and the story itself (or "prehistory," as it somehow called Marx) will end together with the operation of its laws, and the new revolution must find its strength and attractiveness in the way of the future, not the past. So it is possible to comment on the passage:

"The social revolution of the nineteenth century can draw its poetry from the future, not the past. She may begin to perform its own task before it does not do away with all the superstitious reverence of antiquity. Former revolution needed the memories of world-historical events of the past, to deceive itself about its own content. Revolution of the nineteenth century must provide dead to bury their dead, to understand their own content. There was a phrase above the content, here the content is the above phrase".

Here, among other things, a curious use of the word "poetry" in relation to "social revolution". On the one hand, Marx clearly a substitute key for the present, only acquiring its current sense, the concept of "ideology" — "poetry"; on the other hand, instead of the word "poetry," modern man would put this phrase difficult to understand the word "image" or "image": "the Social revolution of the nineteenth century can draw material for creating your own image of the future, not the past" — so, apparently, would be expressed today marks. Note also that because the "future" is only a "image" "image" — it turns out that this image is constructed from image of the future, which, of course, consists of materials present. The circle closes, we find ourselves in the same prison of modernity.

© Eugene Atget

Endure the present, nothing more

"Part of the proletariat indulges into doctrinaire experiments, the establishment of exchange banks and workers' associations — in other words, in a movement in which it renounces the idea to revolutionize the old world, using the collection lies in the very old world move, and trying to exercise their liberation behind companies, private way, within the limited conditions of existence and therefore inevitably fails. The proletariat, apparently, unable to find their former revolutionary greatness in itself nor to draw new energy from the newly alliances until all the classes with which he struggled in June will not be as thrown as he is".

Classical Marxism have to admit the action of the historical laws which he himself had formulated, but he does not trust them, he is burdened by them and uses them for their own abolition.Of course, neither the proletariat per se, nor its economic and any other condition of Marx itself is not interested; he sees in the proletariat only the agent of crushing, the final revolution, which will destroy the old world and stop, finish the story. Because it does not matter whether the proletariat is trying to improve his position here and now with all sorts of mutual funds and other things; on the contrary, in some sense, the worse the work, the faster they will open the undisguised truth of exploitation and at the same time the truth of the doom of the old world, the sooner they will strike at the goal, not exchanged for all sorts of stuff, like Legislative Assembly, parliamentary life, etc. that's not even pragmatism, and some enthusiastically Machiavellianism Marx inherited Lenin who put it into the base of its political strategy and tactics. For different funny and not serious (from his point of view, frivolous, of course), events like the overthrow in 1848 the monarchy of Louis Philippe, Marx sees the ultimate goal; any conversation about a specific political, social, economic, cultural situation, it leads, keeping in mind this goal. Predatory confident look of a fanatic-utopian, a look ruthless heliasta, the gaze of the Inquisitor, the Gnostic view that any phenomenon sees the scene of a great Battle of Good and Evil. Interestingly, for Marx, history — despite all the "tactical utility" as material for his historiosophic schemes — there is absolute Evil (hence his words about the "nightmare of the traditions of past generations"), the Good is the termination of the laws of history. Classical Marxism have to admit the action of the historical laws which he himself had formulated, but he does not trust them, he is burdened by them and uses them for their own abolition. Created from the material of historicism, which insists on historicism, classical Marxism recognizes it only as a necessary evil that should explain, use and — in the end — stop.

In this sense, the idea of proletarian revolution and the coming of communism is opposed outwardly very similar to it the idea of progress, that other claims (and crucial element) of the present. Progress represents the total change modern life for the better, but it does not negate this life, its foundations. It is even possible to imagine a kind of organic metaphor, according to which modernity is the root from which will grow the tree of a wonderful future. The trunk, branches and leaves do not look like root, but all together is one thing, because without root there would be the rest. The modernity of the root grows into a tree and the whole tree will be present. Communism in the classic Marxist version sees in modern times a combination of ugly diseased root and its vikorchovivat; Marxist announces vikorchovivat his mission, explaining the structure of the root, whereby the root and gave birth to his killer, and the inevitability of his final death. The act of uprooting of the root makes vikorchovivat free from the root, respectively, from the present. In fact, even no matter what is in the hole left from the root; that is why revolutionary Marxism in such a vague outline of a bright future.

Therefore, it is not true to popular beliefs about the true relation of Marx's (almost invented) the dual pattern of "progressive" vs. "reactionary". The Marxist approach to the past and the present is only partly fits into this scheme; the boundary of its influence is "the collapse of the old world". Isaiah Berlin writes about the laws of social development revealed by Marx: "furthermore, these laws define what is progressive and what is reactionary, that is, which corresponds to the native the inherent human goals, and what contradicts them." This is true, but in a certain framework. "Progressive" is good only to the limit of the old society, it contributes to progress in the understanding of Marx, contrary to the idea of progress characteristic of modernity, more precisely to the bourgeois consciousness. The Marxist "progressive" — the ability of public (and other) events to push the old world to its end. And that's all. In this sense, "revolutionary" and "progressive" are two different things. "Progressive" unconscious teleological way contributes to the inevitable downfall of the world of exploitation; the revolutionary uprooting this world, as a prologue to the new world, marvelous. Because "progressive" is the second grade in respect of "revolutionary" — it can only be sympathetic to endure from time to time, nothing more. As a matter of fact, and modernity for Marx (who did not know of the concept, but did a lot for the formation and define the meaning of this era) is that the revolutionary is to suffer, there is no other way. A radical departure from the past, including from the past inside the present, is one of the main tasks of the true revolutionary.

The text of the "Eternal present: marginal notes, "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte"" were also published on the website UFO.

Source: theoryandpractice.ru

© Eugene Atget

Understanding of class struggle by Karl Marx intersects with the notion of modernité (modernity, modernity), which is one of the first comprehended Charles Baudelaire. The coming revolution is not focused on gradual improvement (progress), but, paradoxically, must break with modernity, embodied in itself is. T&P publishes an excerpt from a new book by historian and essayist Kirill Kobrin "Modernitè in selected stories", published by the HSE.

In 1864 in London, in the concert hall of St. Martins Hall in Covent garden, was created by the First international (International Association of workers); in the constituent Assembly was attended by Karl Marx, who was elected to the leadership of the new organization. He also asked to write the inaugural address and provisional rules of the Association. One hundred years later, in 1964, Isaiah Berlin's essay "Marxism and the international in the nineteenth century" gave a compact, surprisingly clear presentation of the theory of Marx and its subsequent adventures; the author timed his text for the centennial of the First International Association of workers. Twelve years before the founding meeting of the First international in St. Martins Hall, Karl Marx publishes in the German-language journal Die Revolution, which was published in the US immigrant Joseph Weydemeyer, a great political pamphlet "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte", where in hot pursuit analyzes the developments in France from the February revolution of 1848 to the establishment of the Second Empire. Marx wrote his work at a time when new prospects (called "Bonapartist") regime was very vague; the author's conclusions were accurate, and it is allowed to republish the work when the life of Marx in 1869-m, a year before the collapse of the regime of Napoleon III.

In the Preface to the first reprint Marx writes that practically did not change the text seventeen years ago; he thereby hints: it contained a new approach to political analysis is much more important than the political turnover because, for example, can not explain the German reader 1869 French personalities 1849. In other words, we have before us a theoretical essay, one of the cornerstones of the building of the theory of class struggle and the proletarian revolution; moreover, the "Eighteenth Brumaire" — I think the first essay of Marx, where he methodically and deliberately used only the created concept to the important political events of the time strongly influenced all of Europe. And although in the Preface to the first reprint Marx argues that undertook this work out of a desire to help colleague, started a radical political weekly, however, as often happens, the temptation to use the latest vseobyasnyayuschego revolutionary concept for the explanation of the freshest of the revolution on a European scale (not to mention the fact that by the beginning of 1852 many other European countries raging there revolution has only just calmed down or been suppressed) overcame a casual, almost "customized" nature of the work. Masterpieces not necessarily born from the intention to create such, slowly working in quiet offices, after diligent preliminary work and solitary walks through the countryside. Often, if the author's idea is already "ready" to work, and on the horizon looms no office, no free time, nor even the path in the middle of a peaceful green pastures — everything is different, and from the nature of the light of God is the uncorrupted value (or apparent as such). Apparently, the same thing happened with "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte", which, of course, there's a kind of masterpiece of political thought and ideological calculation.

Moreover, in the third, posthumous German edition of the pamphlet, 1889-m (remember, that year was established the Second international) "the Eighteenth Brumaire" is called Engels "brilliant", after which his Preface is followed by this passage:

"It marks the first time discovered a great law of motion of history, the law according to which every historical struggle — whether it takes place in the political, religious, philosophical or any other ideological sphere is in reality only a more or less clear expression of the struggle of social classes, and the existence of these classes and at the same time their collisions among themselves in turn determined by the degree of development of their economic status, the nature and mode of production and defined by the exchange. This law, which was Central to the story is the same value as the law of transformation of energy for science, was to Marx and in this case, the key to understanding the history of the French Second Republic. In this story he is in this paper tested the validity of the open of the law, and even thirty-three years later still it should be recognized that this test gave excellent results."

So, if the first German re-release has been started, to remind the reader — and it was already the reader is quite different than in 1852, in front of us the audience of the First international — the fundamentals of the theory of the class struggle, the second is already triumphantly showed the social-democratic Second international audience not only theoretical, but practical and political correctness of Marx. Second Empire ignominiously collapsed, revealing its rotten to the core, about which so much is said in the "Eighteenth Brumaire", the Paris bourgeoisie has made another revolution, again, exactly according to Marx, exposing the weakness of her, followed by the Paris Commune — that is, Marx predicted social revolution, proletarian (here it does not matter that the original theorist was regarded practices-the Communards pretty cool and disbelief).As you can see, closely are related to two of the revolution (1848-1849 and 1870-1871), two international (First and Second) and two pieces about the same size: "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" Karl Marx and "Marxism and the international in the nineteenth century," Isaiah Berlin. At the intersection of these events and texts, I will try to build your own text. The main object of analysis will be the "Eighteenth Brumaire"; essays of Berlin (in itself wonderful!) there is here almost invisibly and it is mentioned only in a few places. Finally, I drew another material, which neither Marx nor the Berlin stories related to public, cultural and ideological history of the Second Empire. Chief among them is the notion of modernity, modernité appeared (due to the efforts of Charles Baudelaire) in those years and in Paris.

As is well known, Walter Benjamin first brought together Marx and Baudelaire in the analysis of this plot; since then the writings on the cultural history and the history of ideas, this combination has become almost classic; but despite the attention to the topic, today one can hardly speak about her exhaustion. In particular, fundamentally important is the question of our own position on this key period in the history of the West, when Paris was, in the words of Benjamin, the "capital of the nineteenth century." Where is today's Western consciousness outside or inside of that period, the determination (and even the content itself) which was minted between the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte and judgment of "Madame Bovary"? Currently, the most common answer to this question is negative, they say, present in the past, we have been in the post-stage; well, let's see if we can put this answer into question.[...]

Class struggle vs. stuffy clubs perfume

The most interesting topic today "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" is associated with the ratio of stories, "repeated twice" (the famous opening sentence of the pamphlet), and the revolutionary interpretation of history, which comes from the unheard-of principle of the class struggle. Early revolution (from the first half of the XVI century — if you count the Reformation as a "revolution", as did Marx and Engels — until the second half of the eighteenth century) to dress in clothing of the past to prove its relevance, correctness, to legitimize themselves. New things come in old clothes, all patterns, images and rhetorical figures set old time. There are two poles of Antiquity and the old Testament. The first model — for social revolutions, the second for the reformation and subsequent Protestant movements; that is to say, Athens and Jerusalem, the dual scheme, which, as we know, Lev Shestov, exhausts European tradition. At the same time conservatism, any conservatism, "counter-revolution" is preferred as the material for its ideological constructs are quite different historical periods, as well as non-European culture — the New Testament instead of the old, the Middle ages instead of classical Antiquity, Oriental despotism and China instead of Athens and Rome. But after 1815 th there is a major modification: radical movements and revolutions deliberately imitate the great French revolution (and some of the War for independence of North American colonies). There is already a very different, consciously "modern" type of historical legitimation of opposing the enforcement. After 1815, the progressives and radicals, as before, look back, however, they deliberately short-sighted and then Robespierre (or, a little later for Europe and as another option, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington) don't see anything suitable.

Modernity becomes the source and the result of itself; at the same time she often despises it, hoping to get rid of any past.For Marx, this "myopia" for the incarnation is not authentic; the way out is not authentic, a breakthrough to the truth he sees not a return to the retrospective "hyperopia", and focus exclusively on the present. As a tool of analysis, the only true interpretation of the mechanism he proposes the concept of class struggle, rooted in the past (the past can — and should — be subject to the application of this concept, but in the past it was not). New is read using the new — in this sense Karl Marx, along with Charles Baudelaire, perhaps the main Creator of the concept of modernity, produced from material of our time. Modernity becomes the source and the result of itself; at the same time, as we see in Marx, she often despises it, hoping to get rid of any past.

Roberto Calasso notes:

"The word vulgarité introduced by Madame de Stael in 1800. Modernité we meet in théophile Gautier's 1852-m. But in the "Sepulchral notes" Chateaubriand, published in 1849, these two words stand side by side in the same phrase that describes problems the author has encountered Wurttemberg customs: "the Vulgarity, the modernity of customs and passports". If fate had appointed these two to be together. That was before? Was a vulgar person, but was not vulgar. And were modern people, but it was not present. (...) Modernity: the word that appears and runs between Gautier and Baudelaire in the Second Empire, in a period of just over ten years, between 1852 and 1863. And every time it is presented gently, with the understanding that the present their language to a foreigner. Gautier (1855): "Modernity. Is there such a noun? The feeling which it expresses, is so recent that this word is likely not in the dictionary". Baudelaire (1863): "He's looking for something that we are allowed to call modernity, insofar as there is no better word that expresses this idea." But that was the idea, so fresh and implicit, to Express which there was not yet refer to? From what has been made modernity? Evil Jean Rousseau then declared that modernity consists of women's bodies and trinkets. Arthur Stevens, defending Baudelaire, first called the poet a man, "which, I think, invented the word, modernity." Through painting and frivolity this word into the dictionary. And it was doomed to gain a foothold there, growing, conquering and devastating — new areas. Soon no one remembered his modestly-frivolous beginning. From Baudelaire, however, the word remained in the clubs of powder and perfume".

Pay attention to two things. First: modernité appears along with the Second Empire, perfectly coinciding in time with the development of a Mature Marxist theory. Where Gauthier sly kick sends the ball in the modern field of Baudelaire, and is the final point "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" by Karl Marx. Second, for Baudelaire that was forged out of this concept, modernity of art — and in this case it writes about art is when its object shall be elected not "sanctified vegetables" plein air, brothels, parks, dancing halls and avenues, that is what exists now and in its current form relatively recently appeared in the city life. The very contemporary city, with its vices, obscenity, accessible to women, shrouded in stifling clouds of perfume, is the embodiment of modernité. Similarly, Marx believed the true revolution is only the one that thinks itself a part of modernity and not disguises itself in "consecrated by antiquity."

The revolution is afraid of its novelty, its modernity, is afraid of himself as a "revolution."Modernity is ambivalent: she is trying to build their genealogy to its own past and simultaneously denies the need for genealogy as such. Artistic vanguard of the XX century in its beginning is even more exposed this duality: dropping from the ship of modernity past, he simultaneously attempts to find predecessors, and in the most random and illogical, it would seem, of contexts, beyond the mechanism of "myopia." Modernity doesn't trust the past, even his own, but to be in a situation of "pure this" or even "clean future" is afraid. Hence the attempts, for instance, of the Surrealists to make a list of their own great — totally random — predecessors. It ends not with a Bang but a damning irony in Borges's essay "Kafka and his precursors", and his imaginary literary and philosophical pedigrees. The fight against the "nightmare of the traditions of past generations" through his denial and attempt to establish power over him through an arbitrary point of the choice of their predecessors ends complete mystification of the past, the final deprivation of any meaning except decorative (as in the same of Borges, and in the worst case, as his epigones type of Milorad pavić).

The prison of modernity

Moving on to the next question: why the revolution, the main (along with progress) invention of modernity, this old outfit? Marx's answer is: from time to time revolution is ashamed (or afraid) of its true content, attempting to offer to yourself and others something more "noble" and "legitimate" (which means — rooted in history, in "the traditions of past generations"). In other words, the revolution is afraid of its novelty, its modernity, is afraid of himself as a "revolution." The first revolution of turning to Ancient Greece and Rome, but later — in fact, to the first two revolutions. That is why so very important War for US independence and the French revolution. But then the following question arises. Why Marx believes that in the mid-nineteenth century, such thinking is shameful and napolino? The answer is simple: changed the very content of the revolution. The bourgeois political revolution is transformed into social (with the prospect of a purely proletarian). After the proletarian nothing will happen and the story itself (or "prehistory," as it somehow called Marx) will end together with the operation of its laws, and the new revolution must find its strength and attractiveness in the way of the future, not the past. So it is possible to comment on the passage:

"The social revolution of the nineteenth century can draw its poetry from the future, not the past. She may begin to perform its own task before it does not do away with all the superstitious reverence of antiquity. Former revolution needed the memories of world-historical events of the past, to deceive itself about its own content. Revolution of the nineteenth century must provide dead to bury their dead, to understand their own content. There was a phrase above the content, here the content is the above phrase".

Here, among other things, a curious use of the word "poetry" in relation to "social revolution". On the one hand, Marx clearly a substitute key for the present, only acquiring its current sense, the concept of "ideology" — "poetry"; on the other hand, instead of the word "poetry," modern man would put this phrase difficult to understand the word "image" or "image": "the Social revolution of the nineteenth century can draw material for creating your own image of the future, not the past" — so, apparently, would be expressed today marks. Note also that because the "future" is only a "image" "image" — it turns out that this image is constructed from image of the future, which, of course, consists of materials present. The circle closes, we find ourselves in the same prison of modernity.

© Eugene Atget

Endure the present, nothing more

"Part of the proletariat indulges into doctrinaire experiments, the establishment of exchange banks and workers' associations — in other words, in a movement in which it renounces the idea to revolutionize the old world, using the collection lies in the very old world move, and trying to exercise their liberation behind companies, private way, within the limited conditions of existence and therefore inevitably fails. The proletariat, apparently, unable to find their former revolutionary greatness in itself nor to draw new energy from the newly alliances until all the classes with which he struggled in June will not be as thrown as he is".

Classical Marxism have to admit the action of the historical laws which he himself had formulated, but he does not trust them, he is burdened by them and uses them for their own abolition.Of course, neither the proletariat per se, nor its economic and any other condition of Marx itself is not interested; he sees in the proletariat only the agent of crushing, the final revolution, which will destroy the old world and stop, finish the story. Because it does not matter whether the proletariat is trying to improve his position here and now with all sorts of mutual funds and other things; on the contrary, in some sense, the worse the work, the faster they will open the undisguised truth of exploitation and at the same time the truth of the doom of the old world, the sooner they will strike at the goal, not exchanged for all sorts of stuff, like Legislative Assembly, parliamentary life, etc. that's not even pragmatism, and some enthusiastically Machiavellianism Marx inherited Lenin who put it into the base of its political strategy and tactics. For different funny and not serious (from his point of view, frivolous, of course), events like the overthrow in 1848 the monarchy of Louis Philippe, Marx sees the ultimate goal; any conversation about a specific political, social, economic, cultural situation, it leads, keeping in mind this goal. Predatory confident look of a fanatic-utopian, a look ruthless heliasta, the gaze of the Inquisitor, the Gnostic view that any phenomenon sees the scene of a great Battle of Good and Evil. Interestingly, for Marx, history — despite all the "tactical utility" as material for his historiosophic schemes — there is absolute Evil (hence his words about the "nightmare of the traditions of past generations"), the Good is the termination of the laws of history. Classical Marxism have to admit the action of the historical laws which he himself had formulated, but he does not trust them, he is burdened by them and uses them for their own abolition. Created from the material of historicism, which insists on historicism, classical Marxism recognizes it only as a necessary evil that should explain, use and — in the end — stop.

In this sense, the idea of proletarian revolution and the coming of communism is opposed outwardly very similar to it the idea of progress, that other claims (and crucial element) of the present. Progress represents the total change modern life for the better, but it does not negate this life, its foundations. It is even possible to imagine a kind of organic metaphor, according to which modernity is the root from which will grow the tree of a wonderful future. The trunk, branches and leaves do not look like root, but all together is one thing, because without root there would be the rest. The modernity of the root grows into a tree and the whole tree will be present. Communism in the classic Marxist version sees in modern times a combination of ugly diseased root and its vikorchovivat; Marxist announces vikorchovivat his mission, explaining the structure of the root, whereby the root and gave birth to his killer, and the inevitability of his final death. The act of uprooting of the root makes vikorchovivat free from the root, respectively, from the present. In fact, even no matter what is in the hole left from the root; that is why revolutionary Marxism in such a vague outline of a bright future.

Therefore, it is not true to popular beliefs about the true relation of Marx's (almost invented) the dual pattern of "progressive" vs. "reactionary". The Marxist approach to the past and the present is only partly fits into this scheme; the boundary of its influence is "the collapse of the old world". Isaiah Berlin writes about the laws of social development revealed by Marx: "furthermore, these laws define what is progressive and what is reactionary, that is, which corresponds to the native the inherent human goals, and what contradicts them." This is true, but in a certain framework. "Progressive" is good only to the limit of the old society, it contributes to progress in the understanding of Marx, contrary to the idea of progress characteristic of modernity, more precisely to the bourgeois consciousness. The Marxist "progressive" — the ability of public (and other) events to push the old world to its end. And that's all. In this sense, "revolutionary" and "progressive" are two different things. "Progressive" unconscious teleological way contributes to the inevitable downfall of the world of exploitation; the revolutionary uprooting this world, as a prologue to the new world, marvelous. Because "progressive" is the second grade in respect of "revolutionary" — it can only be sympathetic to endure from time to time, nothing more. As a matter of fact, and modernity for Marx (who did not know of the concept, but did a lot for the formation and define the meaning of this era) is that the revolutionary is to suffer, there is no other way. A radical departure from the past, including from the past inside the present, is one of the main tasks of the true revolutionary.

The text of the "Eternal present: marginal notes, "the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte"" were also published on the website UFO.

Source: theoryandpractice.ru