253

BRUSSELS BRAIN: The cervical plexus and emotions

Description: The article reveals the concept of the “abdominal cord” and explains how the plexus and gallbladder are related to our emotions. The physiological and psychosomatic aspects of the interaction between the abdominal organs and human emotional reactions are considered.

Introduction

Often in colloquial speech, you can hear expressions like “I have a twist in my stomach” or “I smell my gut.” These phrases, while metaphorical, surprisingly reflect the real connection between our emotional state and the abdominal cavity. Medicine and neuroscience have been studying the cerebral plexus, also called the solar plexus, for decades and are finding more and more evidence that this node of nervous structures serves as a kind of “second brain”. In other words, many emotions and first physiological reactions actually pass through the “center” of our abdomen.

When it comes to strong feelings – fear, joy, or sudden excitement – we often catch their effects in the abdomen. Why did nature need to connect our emotional well-being with the work of the digestive organs? Why do we often feel cramps or heaviness in our stomach when we are anxious or angry? And is the role of the gallbladder in emotional responses really so great? We will try to understand the mechanisms underlying this amazing phenomenon, based on scientific data and psychosomatic concepts, and consider what benefits can be derived from understanding the abdominal cord for maintaining health.

Main part

1. The plexus as a “second brain”

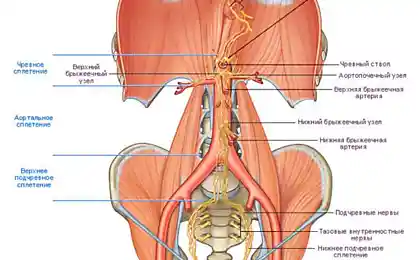

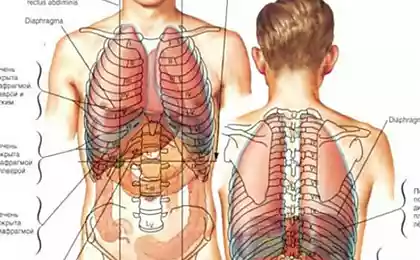

The plexus (or solar plexus), located approximately at the level of the upper abdomen and behind the stomach, is a knot of large nerve fibers connected to each other and form a complex communication network. It is considered one of the most important nodes of the autonomic nervous system. Scientists have long noticed that the volume of nerve cells, as well as the complexity of interactions, the plexus can be called a kind of “second brain” of a person.

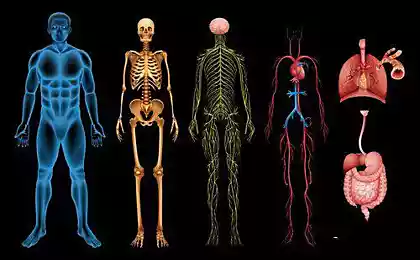

According to a number of studies conducted in the field of neurogastroenterology (see Wikipedia), this “second brain” has more than 100 million neurons that coordinate the process of digestion and transmit signals to the brain. At the same time, these signals are not limited to such simple reactions as feeling hungry or full: their spectrum is much wider and includes emotional and pain components. This is why we often say that we “feel something in the stomach” without having clear mental formulations in our heads.

This whole system is called the enteric nervous system. It is able to act autonomously from the central nervous system, regulate the motility of the stomach and intestines and greatly affect our general well-being. Some researchers point out that up to 90% of serotonin in the body is produced in the gut, which may play an important role in mood formation and resistance to stress.

2. Emotions and gallbladder: why it’s important not to “swallow” irritation

According to traditional oriental medicine, the gallbladder is often associated with a tendency to determination, courage and the ability to make important decisions. In classical Western psychological metaphors, the expression “pour out bile” is rooted, which implies the outburst of anger or irritation. Modern psychosomatics offers its own explanation: when we accumulate anger or resentment and do not express it for a long time, the gallbladder can experience an increased load, and the bile separation can be disturbed.

The plexus, being a kind of “nervous control node” in the abdominal cavity, closely interacts with the gallbladder and liver, transmitting signals about stressful states. When a person experiences intense emotions, such as anger, fear or joyful arousal, the sympathetic department of the autonomic nervous system is involved, increasing the production of adrenaline, increasing the tone of the smooth muscles of the intestine and biliary tract. If such conditions become chronic, the general rhythm of the digestive system is disturbed, increased irritability appears, and sometimes pain in the upper abdomen.

- Anger and irritation: In psychosomatics, it is believed that the suppression of these emotions can provoke stagnation of bile, increasing the risk of developing gallstone disease.

- Fear and anxietyLead to spasms of smooth muscles, which affects the condition of the stomach and duodenum. Sometimes this manifests itself in the form of a “squeezing” feeling under the spoon.

- Joy and euphoria: Positive emotions stimulate the release of endorphins and improve peristalsis, which ultimately affects the general well-being and bowel function.

Thus, the gallbladder, like other organs of the abdominal cavity, actively responds to emotional fluctuations, especially if they are associated with outbursts of anger or outrage. The root of this connection is in the general vegetative regulation, which is coordinated by the cerebral plexus, responsible for the operational distribution of “alarm signals” through the organs of the abdominal department.

3. Mechanisms of interaction of body and emotions

To understand exactly how the plexus “communicates” with our emotions, it is necessary to consider the mechanisms underlying the autonomic nervous system (ANS). This system, divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic departments, regulates involuntary body functions - heart rate, respiration, vascular tone, secretion of glands. With regard to the abdominal cavity, the following key processes can be noted:

- Sympathetic activation. When stress occurs, the brain (through the hypothalamus) sends impulses that make the heart beat faster and constrict blood vessels in the gastrointestinal tract. At this point, the plexus transmits signals to the digestive organs, reducing the activity of their work, as the priority becomes “fight or flight”.

- Parasympathetic braking. When the crisis is over, the parasympathetic department returns the body to a state of rest. The plexus “weakens” its tone, allowing digestion to work again in normal mode. In this state, we feel relaxed, calm and "warm in the stomach."

- Hormonal regulation. The adrenal glands, under the influence of signals from the ANS, secrete stress hormones (adrenaline, cortisol). These hormones through the bloodstream reach the abdominal cavity, affecting the gallbladder, pancreas and liver. With constant stress, cortisol levels can negatively affect immunity and the general tone of the body.

- Intestinal neurotransmitters. Serotonin and dopamine, commonly associated with the brain, are actually synthesized in significant amounts in the gut. They affect not only mood, but also motility of the stomach and intestines, giving additional confirmation of the concept of the “abdominal cord”.

All these processes together create a single system capable of responding to external factors and internal experiences. As soon as a person begins to experience an emotion, whether it is joy or anxiety, the corresponding signals from the brain or from the external environment are converted into neurochemical messages that immediately reach the plexus and digestive organs.

4. Psychosomatic aspects of the “abdominal cord”

Often, we tend to underestimate the importance of bodily signals that arise from nervous tension. Meanwhile, numerous studies on psychosomatics (see Wikipedia) indicate that repressed emotions find an outlet in the form of somatic symptoms. If a person is inclined to “swallow resentment” or “accumulate anger inside”, the abdominal cavity, and especially the gallbladder, can fail and signal pain, digestive disorders or stagnation of bile.

On the other hand, awareness and adequate elaboration of emotions give us the opportunity to improve the general condition, increase stress resistance and overall quality of life. The easiest thing to do is to start paying attention to how your body reacts to certain stimuli. If there is a conflict or an unpleasant experience, it is worth noting: did not the stomach “compress” or did tension arise in the solar plexus? This awareness opens the door to understanding how actively the abdominal cord is involved in our emotional processes.

5. Practices for harmonizing the plexus

Fortunately, there are a number of techniques that help to establish contact with your body and “calm” the overactive abdominal brain. Below are some of them:

- Breathing exercises. Slow breaths and exhalations, accentuated on the diaphragm, help reduce sympathetic activation and activate the parasympathetic department. This helps to relax the walls of the stomach and normalize peristalsis.

- Yoga and stretching. Practices, including soft twists and tilts forward, help improve blood circulation in the abdomen and make it possible to “reset” the work of internal organs. Yoga specialists often emphasize that such exercises reduce tension in the solar plexus.

- Belly massage. Light circular clockwise movements in the navel area can stimulate the release of stagnant bile and improve digestion. At the same time, it is important not to press too much and monitor your own feelings.

- Conscious eating. Pay attention to how you eat. Try to chew food slowly and consciously to signal the parasympathetic department to start normal digestion and reduce stress levels.

- Psychological practices. Regular reflection, keeping a diary, contacting a psychotherapist with chronic emotional clamps - all this helps to release repressed feelings that can negatively affect the health of the plexus and gallbladder.

It is important to understand that working with emotions and physical sensations in the abdomen is a complex process. There is no single magic pill, but there is a wide range of practices, each of which can contribute to the overall recovery and improvement of the emotional background.

6. Ecology of Health: Synthesis of Bodily and Emotional

In modern popular science literature, the concept of “health ecology” is increasingly found, which implies not only the purity of the environment, but also a careful attitude to one’s own body and psyche. The plexus acts as one of the central elements in this “ecology”, because its balanced functioning largely depends on how we perceive stress and negative events.

Observing the responses of our abdomen, listening to the signals of the internal radar center, we can notice in time that we begin to be angry, offended or anxious. In fact, the abdominal cord acts as an “early detection system” for emotional discomfort. By reflecting on these clues, many people learn to better understand in which situations they suppress feelings or overreact.

The combination of physical and mental practices allows for a more harmonious approach to emotions. Instead of swallowing resentment, we can develop the skill of accepting and meaningfully expressing feelings. Instead of unjustified aggression, seek constructive dialogue. This conscious approach shapes a health ecology in which the body and mind support each other rather than being in conflict.

Conclusion

So, the abdominal cord is not just a metaphor, but a scientifically based phenomenon that plays a significant role in our emotional well-being. The plexus and gallbladder, interacting through the autonomic nervous system, form the first reactions to stress, joy and other strong feelings. This “complex” is able to affect not only digestion, but also general well-being, including mood and level of internal tension.

By understanding the connection between emotions and the state of the abdominal organs, we can manage stress more effectively. Tracking your emotional state, practicing breathing techniques, exercise and developing the skill of conscious nutrition, you can significantly improve the quality of life. Ultimately, this leads to less psychosomatic symptoms, more energy, and better contact with our bodies.

By maintaining a balance between the abdominal cord and the emotional sphere, a person actually strengthens his health ecology, both at the level of biology and physiology, and at the level of the psyche. This integrity not only prevents chronic disease, but also opens the way to a deeper understanding of oneself, one’s place in the world, and one’s own capabilities.

Glossary

- The plexus: a large nerve node in the abdominal cavity involved in the regulation of the digestive organs.

- Autonomic nervous system (ANS): a system that controls the involuntary functions of the body (respiration, heartbeat, digestion).

- Enteric nervous systemPart of the ANS that regulates the activity of the gastrointestinal tract and is able to function autonomously from the central nervous system.

- gallbladder: an organ in which bile accumulates, involved in the digestion of fats and the regulation of digestion.

- Sympathetic activationFight-or-flight state, in which the body mobilizes for stress or exercise.

- Parasympathetic DivisionPart of the ANS responsible for restoring and relaxing the body after stressful situations.

- PsychosomaticsA direction in medicine and psychology that studies the influence of mental factors on physical health.

- Health ecologyAn integrated approach to the preservation and promotion of health, taking into account the interaction of mental, physical and social factors.

Article cycle: Liz Bourbeau. Five injuries. The Trauma of Injustice

How to prepare healthy pickled vegetables without vinegar and sugar