573

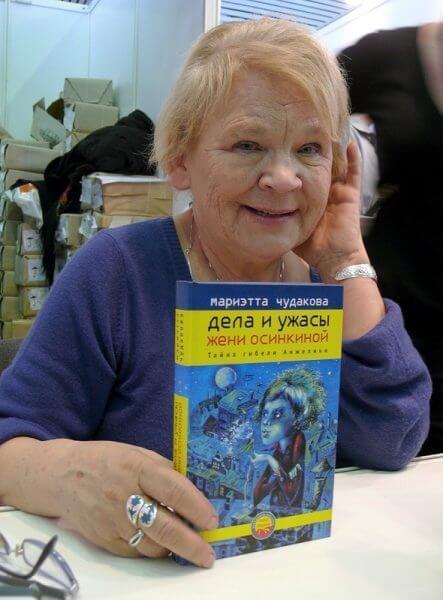

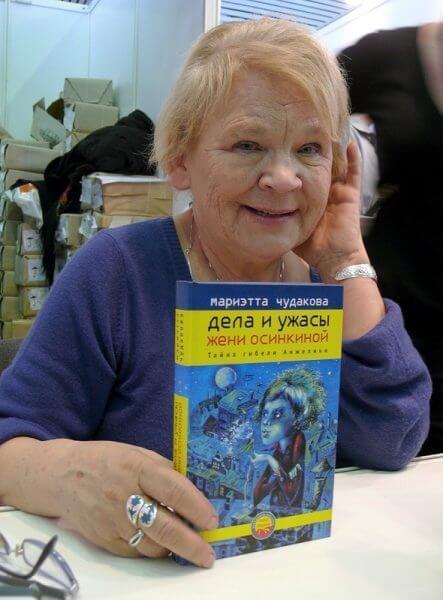

Marietta Chudakova: People do not realize what year awaits us

For 20 years, the well-known literary critic and public figure Marietta Chudakova has been engaged in a special business, or rather, she performs a feat - she delivers the necessary books to school libraries, meets with teachers, librarians and schoolchildren in the most remote villages, conducts lectures.

In Yekaterinburg, Marietta Omarovna recently held a meeting with the intelligentsia and told about whether it is necessary to read to children about repression and why a boy at 12 should know that the fate of the Motherland depends on him.

Mariette Chudakova is 80 years old.

How the Military Helped Education

- In 1996, I was a member of the Presidential Council and a member of the Presidential Pardon Commission. It was an election year. I was in favor of Yeltsin being elected for a second term, not Communist Zyuganov. I appealed to Yeltsin’s assistant, Georgy Aleksandrovich Satarov, telling him: “George Aleksandrovich, I have this idea: since there is such an active presidential campaign, it would be good for the members of the Presidential Council to go to those remote places in Russia where the President obviously will not get, and help people with something.” He said, "Great idea! Do you know what you would like to do? I'm like, "I totally know." I know that since 1990, no books have been sent to rural schools, and the acquisition has ceased. And during these five or six years, what we intellectuals dreamed of all our lives was published: Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Pasternak, everything in the world. I want to take these books to rural school libraries.”

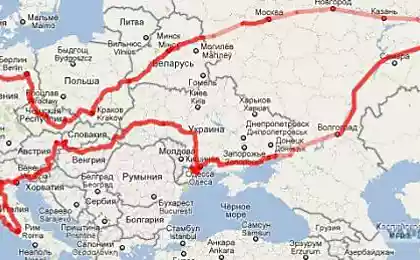

He started doing this very correctly: he called the Ministry of Defense to help me – to deliver me on a military board. I chose the territories - Samara, Tyumen regions and the Altai Republic. And I flew to the Samara region, distributed books, flew to Tyumen – there I took books and military units, abandoned deep in the birch, where no human foot does not step. Then he called me as a military officer: “Come, we do not let anyone – here the subberezoviki sloshing carpet, come, pick up mushrooms!”

Then I flew late in the evening to Novosibirsk to go to the Altai Republic. Why Novosibirsk and not Barnaul? Barnaul did not accept military aircraft. This was my third item and I had the last third of my cargo on board – 300 kg. From this it is clear that I could only work with the military board, the Ministry of Defense. I was met by the government GAZ, and I drove all night – 9 hours – to the Altai Mountains.

Satarov warned me: “Keep in mind, Marietta Omarovna, that your position as a member of the Presidential Council is higher than that of governors.” I say, “I don’t care, I always behave the same way, I can’t blow my cheeks.” But there, in front of me, the chairman of the local government moved also because I noticed that there were only red flags on the city square; everyone in the government was for Zyuganov, but they had to disguise themselves as Yeltsin. All were Stalinists (the farther to the outback, the more it was).

So we are sitting with the then Prime Minister, discussing the protocol of my stay in the Republic. Suddenly the door opens, the young man’s desperate face appears: “Are you a member of the Presidential Council?” Seventy Afghans are waiting for you! And this one, Petrov, shouted at him: "Andrey, go, we are not doing this here, we are drawing up a protocol!" I looked at the desperate eyes of a young man (who was the chairman of the Independent Union of Afghan Veterans), understood everything in a second and said: “Andrey, sit in the corridor and wait: we will draw up a schedule, and I will certainly meet with your Afghans today.” The Prime Minister did not want me to meet with the Afghans, but he could not go against me. He slammed the door, waited, and then drove me. So I met Andrey Mosin, with whom we have been traveling around the country for twenty years. I later learned that he was the best scout in the 40th Army in Afghanistan.

The Union had its own room at the time. When we arrived, we could not enter there, we could suffocate, so smoked, and already they drank, of course (waited for an hour and a half). Hands on the table with clenched fists...

Their first words were: “Marietta Omarovna, are you a member of the Presidential Council?” There's only commies in the government! Give us the vending machines, we'll cut them, and it's over.

When I got home and told my husband, he was horrified: “I can’t imagine what you could say to them?” I said, "Yes, I answered perfectly: "Guys, do you have the Supreme Commander-in-Chief?" - "Of course - Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin!" When the Commander-in-Chief tells you to take the machines, you will take them! In the meantime, only in a peaceful way! And she banged her fist on the table for persuasiveness. And they calmed down, these words worked for them.

Then they tell me: “You don’t go with the government – they will show you Potemkin villages, come with us.” And for three days I drove around the Altai Republic in their cars with prepared sets of books for schools. I barely slept; we went to forty schools. If I had slept, we would have traveled half as much. There is only a car, there is no railway. The farthest area, Kosh Agach, in the 300s, seems to be kilometers from the capital. City one is the capital. And just sat down.

But I saw some amazing things (I'm sure every city, if not every school, has a very good dictionary, at least one): teachers took books and pressed them to their chests, tears on the cheeks of the lyricists are real:

“My God, I don’t believe what Mandelstam has in my hands! I can't believe I'm holding Akhmatova! That I can teach Pasternak from books, not from university notebooks! It was something incredible.

I sat with them in the teacher’s room and talked. It was the 96th year, they were not paid salaries for months, there were no textbooks, notebooks. And they told how the school started a new course, what a teacher dreamed of all his life - embroidery of a special type or lace, as introduced on their own initiative different classes - both mental and manual. They were delayed. And I asked them the same question everywhere, in all forty schools: Imagine that from tomorrow everything comes back to normal: you will have on time salaries, textbooks and notebooks you will be provided, but no extra electives, one program for the whole country and just like before, you write a report monthly headmaster, headmaster in RONO, RONO in GORONO ... What would you choose? I was no boss, I explained that I am on a voluntary basis, from the Presidential Council, their life does not depend on me. And everyone, absolutely everyone, after a little thought, answered that no, still no. They didn't want to come back. Here is the answer about Soviet power and attitude towards it. I saw it in the most difficult time (in Moscow everything was already arranged, and they had it).

After I saw the impact of these deliveries on teachers, school librarians, I knew that this had to continue. And I started thinking about how to do that.

Books for teenagers for their money

Eight or nine years ago, one project was formed: professors-historians, teachers of the Higher School of Economics and History Department of Moscow State University, realized that now the most difficult time for teaching history at school is the nineties. So they decided to help the teachers and published four thin books in one design – the project “Lessons of the nineties”, “Book for a teacher”. And I redirected them from teachers to librarians. I was sure that twenty out of a hundred teachers would use these kits, and the other eighty would lie dead in their homes, not distributing them indiscriminately to all teachers, but giving them to libraries. There is only one teacher who wants to use this book.

I started carting books to local libraries, but of course I didn't want to bring them just these books, because their needs were broader. About me learned Chukovsky’s granddaughter (now, unfortunately, the deceased), Elena Tsesarevna, his main heiress, said that she from each edition brought copies, and she will be happy with my help to give them to Russian libraries. Each time before the next trip, I received a suitcase of such beautifully published “cockroaches” and “Moidodyrov” that I myself would read. Now the Chukovsky family continues this.

There is much that can be done in Russia, the country is big, there are many kind and active people, only we are all poorly connected.

The literary agency that worked with Chukovsky’s books also decided to give us books, including translated literature – Hemingway, Dreiser, Fitzgerald – the sixth or seventh edition, and the heirs of the translators, of course, do not take them anymore. From time to time, Tatiana Sokolova, the head of the agency, calls me and says: I have collected books for you, three boxes. They are brought to my small apartment, I scatter all this along the corridor, I lay it out in several suitcases, because I usually travel to two places: I try effectively, but there is no time, I have to do my science.

A wonderful man, an old man already, the son of the well-known Alexander Volkov (“The Wizard of the Emerald City”), and says: “I know this name – Marietta Chudakova, I trust her, I will pass on books to her, just don’t tell anyone that everyone doesn’t bother me.” And he gives me wonderful books Volkov: and “Yellow fog” (I myself did not know – very much loved “The Wizard of the Emerald City”, and this was after my childhood), “The Secret of an abandoned castle”.

But this is not enough, I still buy: freshly published, and their books are not scientific, those, I believe, who needs – he will buy himself, and I wrote a number of books for teenagers: for that they wrote them, so that they reached teenagers, and I see no other way than to buy and deliver, because not all libraries have money, and most importantly – they are not allowed to choose the right literature.

A few years ago, I wrote a biographical novel for teenagers. She wrote on the countertitle: “For intelligent people from 10 to 16 years old”, the book is called “Egor” – about Yegor Gaidar, today it is the third edition. My principle: not to take a ruble from the publishing house for it – I wrote it for purely moral reasons, to restore justice, because to pour slush on such a beautiful person who, one might say, gave his life to his country in difficult years – is deeply unfair and a bad example for children. And I carried about two thousand books around Russia, to city and school libraries, for my own money.

Librarians love my book Not for Adults. Although I wrote it for teenagers, they say, “Well, we give them our explanations, for us this is a recommendation bibliography.” I write essays, they came out in small books: “Shelf One”, “Shelf Two”, and then the publishing house collected a full book, a three-volume, and already three copies, and there are about the best masterpieces of world literature for children.

Twelve years is a very serious age.

I believe that there are no books of world classics that are too early to read, I am a categorical opponent of these “6+”, “12+” – it is unreasonable, because an intelligent child should be ahead of his age, that is the whole point – he should reach out to a book that he is still too early: what is wrong if an eight-year-old child flips through Anna Karenina? He'll see it, he'll see it's grown-up, he'll shrug his shoulders, but he'll remember it and then he'll turn to it. So, There are no books, I write, that are read early, except those that should never be read..

The second law I came up with: There are books that are too late to read.. Anyone will agree with me, no great mind is needed here to understand that if we did not read Tom Sawyer at twelve years old, then, as people say, “we did not soap” – to sit down to read for the first time in forty years! Here you can re-read, remembering childhood impressions, with great pleasure, in the summer in a hammock. But hardly anyone will even be the same Gulliver, Robinson for the first time read in forty years.

I wrote a detective story for teenagers “The Cases and Horrors of Zhenya Osinkina”. The whole detective part is based on real material, which I am too familiar with, because I read, seven years working in the Commission on pardons – was such under President Yeltsin, over the years – I am afraid to say this figure – tens of thousands of sentences.

For example, in my story there is a boy, Vitek, who served three and a half instead of seven – came out on the presidential decree on pardon, he is older than the other heroes. It is based on a very real story that I met in one sentence: adults, twenty-two to twenty-three years old, decided to steal a motorcycle from tourists and ride it, and then return it. A fourteen-year-old boy was put on the scene. And this boy heard screams downstairs, and when he came down, there were already two dead bodies there, because the tourists didn't want to give up the bike. And the villagers did not intend to kill anyone, but there is always a great danger in breaking the law and normal life, which is what I am trying to express in this book. As a result, they blamed it on him that it was almost him, and this boy thundered into the camp for seven years, because he turned fourteen the day before. Although our criminal liability begins at the age of sixteen, but for serious crimes, murders – sorry, from fourteen.

I had an argument at the committee on the subject. The men said he had to leave the crime scene immediately, go to the police and report what he saw. I say: what are you saying, he would not have gone there, he was the main witness: the same guys who were on good terms with him, but when it comes to murders, they would have sewn him on the way. He couldn't do anything. So I told this story in the book.

My main character, Wife, is twelve years old. Some thought it was not enough for such meaningful action. I remember myself very well at that age – it is a very meaningful age, very serious. At the age of twelve, I made some important decisions that I still follow. One of them saved my life this summer.

I decided, no matter what, to exercise every morning. I generally loved sports, was a grader in rhythmic gymnastics already in my graduate years, in general I took sports seriously since childhood, and then maybe my husband influenced (he was in the top ten at our university in swimming), I loved running on skis, and now I run. And I’ve been doing my exercise for countless years — five, six minutes, five, six exercises, no more time, but I can’t sit down to drink coffee without doing it. So, in the summer, I was hit in my yard by a car going in reverse. The blow was very strong, but there were no fractures - only bruises. And the doctor, convinced of this, said that the role of the shock absorber played a muscle corset.

At the age of twelve, I was taking my sister (she is five years younger than me) from Gagra to Moscow, my mother put us on a train (and then it went three days): she was still there, and the elders were supposed to meet us, but did not meet, a mistake happened, and I drove myself from the Kursk railway station to Sokolnikov with suitcases and a little sister. My mother had no doubt that all three days will be fine and I will take her.

The family album opened with a photo of his grandfather, a royal officer.

My grandfather, a native of Dagestan, was a royal officer. In 1917, he told his eldest son, my father: “The Tsar has abdicated, my oath has been lifted – your fate is now in your hands, you can act as you see fit.”

And so it happened that the Pope got into the civil war in the partisan detachment. He wasn't going to be red, it happened: there were national riots, they wanted independence, and there was some communist clever or clever, and he explained to my father that he was not really against the Russians, but against the White Guards. At the age of eighteen, his father became fascinated by the idea of social justice, became a commander of a partisan detachment in Dagestan, joined the party at the age of twenty, then entered the Timiryazev Academy, became an engineer, worked in the fishing industry - designed purse seines, married my mother, a student. Then he went to work in his republic, but this is a special story - he had to take my mother with three children back to Moscow, because my mother could not get rid of tropical malaria, and the doctor said: "You see, we do not work, Dagestanis have immunity, and the Russians are sick: leave, otherwise you will lose your wife."

And he went to Moscow, and two years later, terror began in his homeland. It began with his uncle, one of the then Dagestani People's Commissars and a member of the Central Committee. They killed all the men with his last name, Khan-Magomedov, every one of them.

My grandfather was arrested in 1937, and my father thought it was a tragic mistake. But, as a communist, he believed his party – he believed that if the sentence said “ten years without the right to correspond” – it means that his father is somewhere in the camp. He didn't know it meant a shooting. In 1956, he was given a rehabilitation letter with the words that his father died in 1942 in the camp from pneumonia. My father, though by no means a fool, believed again: understandably a southerner, fell ill with pneumonia and died.

Years after my father’s death, when I was already a member of the Presidential Council, I wrote out the investigation file of my grandfather from Makhachkala and learned that he had been shot two months after his arrest. But – in a rare case – there are protocols of interrogations, each page is signed: he did not agree with anything, took nothing upon himself, denied everything that was lied to him, and everywhere signed with a firm hand. I’ve seen a lot of cases in the FSB archive, and you can always see how page after page of handwriting is completely changed from torture. My grandfather lasted until the end.

We have known for a long time that we took it only on the spot, and if a person lived in another city or in another region, they did not look for him there, they just did not have personnel for this. But we know it retrospectively, and then we didn’t know it at all!

And my father, after the war, when a new wave of arrests and shootings began, undoubtedly waited every day - like the son of an enemy of the people. And I'm amazed and amazed that there was no atmosphere of fear at home. We knew that our father was not afraid of anyone.

There was even material proof of this – our family album of my childhood opened invariably (and even the elders remembered it before the war) with a photograph of an officer grandfather in uniform among his family. And my father never took it out! And people didn’t just destroy the photos, they destroyed the ashes.

Of the three hundred returned one...

The father volunteered to the front, leaving four children and his wife, pregnant fifth, went through the war as a private. And then my brother left, born in 1925, at the conscription – for two months he was trained as a junior lieutenant near Moscow.

My father returned immediately after the victory over Germany at the end of June, and I will never forget that moment. We are waiting for him this day or tomorrow. I stand in the yard with my sister, whom he has not seen (she is three and a half years old), and I shout to my mother: “Mommy, mommy, just entered the porch of my uncle, very similar to our dad.” My mother, of course, had no doubt that I recognized my father-Dagestani, she shouts from the fourth floor: “So run after him!” And we run, I drag my sister so that she does not fall, run into our damp dark entrance and stop stupefying (I will die, I will not forget) – I hear an incredible female cry, and it comes to me that my mother screams – as they shout at the dead in Russian villages, utterly. She met her father, after four years of war, there on our fourth floor, where he took off in two minutes without an elevator.

And then it was even more interesting, like literature. We had two rooms in a communal apartment, they went to their room, locked themselves in, and then she went out to my son (my second older brother, the famous art historian Selim Omarovich Khan-Magomedov, the world’s best specialist in constructivism) and said: “Look, I don’t know what to do.”

We had on the floor a completely wiped palace once sent from Dagestan, and my father, without taking off his boot, lay down on this palace with the words: “Oh, I am tired.” I fell asleep.

She says to her son, What should I do? He's been sleeping like that for hours, maybe waking up? - "Mama, let her sleep." He slept a day. On the floor, naked, in boots. This is Vanshenkin’s amazing poem: “Everyone slept, and Stalin could not reach Zhukov.”

The older brother returned in late September and early October after defeating Japan, like all the officers. He found his comrade, I still remember his surname, Zaitsev, and together they went to the military enlistment office: “Tell me, which of our comrades born in 1925, who were called up at the same time with us from the Sokolniki military enlistment office, returned?” And they found out that out of three hundred boys, three returned to their mothers. This is a statistic: one out of a hundred. Therefore, who still calls Stalin a great commander? Here it is necessary to remember Viktor Petrovich Astafiev (Kingdom of Heaven, eternal peace), I was friends with him, and he fought the whole war as a private, like my father. In a recent interview, he was asked: “Victor Petrovich, who fought better – the Germans or us?” - "Of course, the Germans." - "How did we win then?" I will never forget the look on his face. - We threw corpses at the Germans.

The justification of tyrants is our shame.It seems to me that people do not realize what year awaits us – the centenary of October. I believe that all educated people should feel their responsibility to the younger generations. Every person with higher education should think about how they will work next year.

If we do not dot the i in the year of the century in the history of the twentieth century, then all adult thinking people – a real shame. For almost thirty years after the end of Soviet power, the most important things have not been done. No one has explained the deepest error of Marxism—we have regarded it as the ultimate truth for almost a century—it turns out that the class struggle is by no means the essence of human life, that the meaning of history is not that the workers take property from the factory owners. No one explained that it is impossible to call a great thinker a man who, like Lenin, made a decisive mental error: he was absolutely sure that the revolution would ignite all over the world after Russia.

And it is time to say that our humanitarian work also has axioms, it is time to introduce them. For example, that October was disastrous for Russia, because it led her from the historical path to the historic stall for more than seventy years, or to the historical dead end – who likes what word better. And those who say, “But how hard was it in the 90s,” we ask the question: we are racing along the highway in a car, suddenly we are stopped: “Where are you going, actually?” - "There it is." “The next dead end, you won’t get there.” - "How do we get there?" But here is a countryside, really, a very bad road, but on it you will get to the goal. Then the question is: continue on the highway or turn on the country road?

I conducted such a test on the topic “What is happening to our teenagers?” with the help of librarians of the Bryansk region, Perm region, Kemerovo and Sverdlovsk regions. The research was this: I asked the children a few questions, and they had to write to their teachers. Why not historians? Because no historian of professional honor will let out of his hands the nonsense that his children will write. And the linguists are responsible for Pushkin and Tolstoy, that is another matter.

Everything went well – beautiful in form, terrible in content. The first question is, “What happened in October 1917?” Question: What do you know about Lenin and what do you think about him? What do you know about Stalin and what do you think about him, what do you know about Yeltsin and what do you think about him?

The answers of fourteen-year-old people were a hundred pieces, exceptions - one or two. Lenin was “good, kind, cared about people, created the USSR.” “Yes, he had flaws, some did not like him, others respected him, he sent dissenters to Siberia, there were repressions, but strengthened the USSR, we won the war under him, he was a generalissimo, commander.” Yeltsin – through all the answers to one – “drinked, destroyed the USSR”.

These are all links in one chain. This double, the governor of the Orel region, confident that St. Petersburg was in the XVI century, says that Ivan the Terrible is a great historical figure. He was asked about Stalin: “Stalin is also a great historical figure.” Now wait for the monument to Stalin in Orel - I promise you that.

I went to Orel on purpose and even, trying to stop this madness, made a brochure – I am not a Medievist myself, so the brochure is “Russian Historians about Ivan the Terrible.” In this pamphlet I have shown, with quotes from our best historians, that it was Stalin who had done everything, that he had to find an excuse for terror, and that he exalted Ivan the Terrible. I printed four hundred copies at my own expense, brought them, distributed them there, but apparently there is something missing in our people today... a real charge that does not allow us to justify villains and tyrants.

I think we should all feel the deepest shame that a quarter of a century after Soviet rule, we have busts of Stalin in the European part of the country growing like mushrooms.

History is not driven by a passive majority, but by an active minority. Let them stand, holding hands, and not let it be installed, as in the 70s – at a much worse time! – the students of history, holding hands, did not allow to demolish the chambers of the XVII century in Moscow. I don't understand that, to be honest. We're in our country!

Do many people know that there is a village of Shelanger in the Republic of Mari El? There was a monument to Stalin, five meters. In boots, with an outstretched hand... What will happen to our children? If the adults did, it means the man was good. This bundle remains in force: cruelty, terror can be justified and even bring victory in a war.

I also want to do my scientific work, I study the history of twentieth century literature, I have a separate file in my computer for every year from 1917 to 1990. I would like to sit down and write a conceptual history of twentieth-century Soviet literature. I get distracted all the time. I ask you to help me with a small part of it. Because with the elders who are crazy, and think that everything is right, nothing can be done. But sociologists underestimate this thing: the electorate is a mobile thing: some die, others turn eighteen. We should think about renewing the electorate so that those who enter are smarter than their parents.

Children should know that there were cannibals in our history.

Many believe that children can not talk about repression – they will not love their homeland. And I am absolutely sure that if you do not instill in a child a sense of compassion, until the age of twelve or thirteen, then all is lost. Either he has compassion as a child—animals innocently killed by fellow citizens—or never again, I vouch for it.

Those people who say that history should educate patriotism understand patriotism as a passive feeling: I sit and admire, as on the screen, my history, how Russia was a victorious step from Rurik to Putin, and there was one deviation - in the nineties. Then for some reason they strayed, and everything was so good. A patriotic feeling cannot be passive; it is good only when it is active. Emphases should be rearranged: not “look what a good story we have”, but what among the beautiful pages were terrible – and it depends on you (we are addressing schoolchildren) that they do not happen again! Only effective patriotism and nothing more.

Why not talk about repression? We read children stories about cannibals! And they see that the cannibal is bad. Let them know we had cannibals and they were bad.

This can be explained from early childhood.

Should teenagers read camp memories? Absolutely. I will tell you about one amazing writer, whom no one knows, whose three books I and the head of the historical and literary society “Return” Semyon Vilensky published a long time ago – Georgy Demidov. He is equal in talent to Shalamov, he is the same Kolymman as that. Shalamov, who spoke a kind word about few, wrote in a notebook: “I have never met a person more intelligent and honest than someone Demidov.” An amazing writer.

Semyon Vilensky had a plan to publish in the series “Memoria” the best samples of prose and memoirs about the Gulag. For the eight books in this series, I have written, at his urging, a preface. For example, one of the authors of the series is Olga Adamova-Sliozberg. Her book is published for the third time, and she should be in every school. When you read it, it becomes so clear – to anyone, I think! – Stalin’s time.

She talks about a woman sitting with her in a cell. She has a twelve-year-old son at home. He writes letters to her. He is not happy with one aunt, on the other, he dreams when his mother returns. She says that now the deadline is over, a little more patience. On June 22, 1941, she was released. And an unspoken order: do not release anyone who has expired until a special order. She writes to her son about it. A month and a half later, he wrote to her, Why don’t you write to me? She goes to her boss and says, Your letter is delayed.

A few months later, a letter comes from a stranger: you, apparently, freed yourself and took up your life, and I found your son with a high temperature at some station in Siberia – the boy went to look for his mother. He lives with me now, but what's next?

A few more years pass and she meets her son in a felony camp.

When I worked on the pardon commission (I was the only woman there in recent years) and spoke out in favor of procrastination, the men sometimes objected: what, he has such a bouquet! And I said (the cases were at hand, lying on the windowsill): Show me his first sentence. And I always saw what I thought it would be: 1945-1947. Fourteen, sixteen-year-old boy, it's clear that his parents are there, and he's sitting down for stealing, and then it goes on, and he's got five or six landings.

Tell the boy that everything depends on him!

Patriotism should be brought up on the pure truth, calling children to act, and I am sure that we ourselves stifle in children activity, their natural property. If you meet a twelve-year-old boy somewhere in a deserted place, and tell him: “Only you can help me, I rely only on you!” – he will help you no worse, or perhaps better than an adult. All he has to do is make sure that a grown woman doesn't fool him, and she really needs his help. He'll come out of his skin and help you. We must appeal to an active sense of patriotism: “The fate of the country depends on you!”

What do they hear in their families now? In 2007, we drove the whole country from Vladivostok to Moscow with Andrey Mosin, an “Afghan” – he is driving – and visited seventeen cities and towns. Everywhere I gave books and had a conversation called “The Modern Literary Situation” – what to read in this sea of books. Both librarians and readers had a great interest, but at the end of the day, a purely public conversation always began: I, a Muscovite, was asked questions.

Seventeen cities and towns, at least two auditoriums in each fifty people. And there was no audience – understand! – in which a man would not stand up (and I, excuse me, an anti-feminist, I believe that the Almighty knew what he did when he divided humanity into men and women, besides living in a greenhouse environment as a child, surrounded by real men – a father and two older brothers, they were not afraid of anyone, so when I look at the current weaklings, I can not imagine that they are men, I consider courage, like the mind – the secondary sexual characteristics of a man) and – according to Nekrasov – breeding hopelessly (as if the director said nothing from me): “So it does not depend on us!”

And when Andrey and I got to Moscow, I said to him, “Well, you know what the most common phrase in Russia is?” “Yes,” he says, “I understand everything.” I swear to you, there were no exceptions.

Every family has grown-up dads and moms and they say to each other, ‘Well, you know, it doesn’t matter.’

My opinion (those who have boys, children or grandchildren, nephews, those with me, I think, will agree): if at the age of twelve a boy is instilled that nothing depends on him, he will not be needed in the future by his wife, or an old mother, or, excuse me for his high-mindedness, the Motherland. A boy at twelve must be sure that everything depends on him. Let him be disappointed later. The boy should be encouraged that he can do anything, everything depends on him, and his homeland is waiting for him.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.pravmir.ru/marietta-chudakova-ya-dostavlyala-knigi-voennyim-bortom/

In Yekaterinburg, Marietta Omarovna recently held a meeting with the intelligentsia and told about whether it is necessary to read to children about repression and why a boy at 12 should know that the fate of the Motherland depends on him.

Mariette Chudakova is 80 years old.

How the Military Helped Education

- In 1996, I was a member of the Presidential Council and a member of the Presidential Pardon Commission. It was an election year. I was in favor of Yeltsin being elected for a second term, not Communist Zyuganov. I appealed to Yeltsin’s assistant, Georgy Aleksandrovich Satarov, telling him: “George Aleksandrovich, I have this idea: since there is such an active presidential campaign, it would be good for the members of the Presidential Council to go to those remote places in Russia where the President obviously will not get, and help people with something.” He said, "Great idea! Do you know what you would like to do? I'm like, "I totally know." I know that since 1990, no books have been sent to rural schools, and the acquisition has ceased. And during these five or six years, what we intellectuals dreamed of all our lives was published: Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Pasternak, everything in the world. I want to take these books to rural school libraries.”

He started doing this very correctly: he called the Ministry of Defense to help me – to deliver me on a military board. I chose the territories - Samara, Tyumen regions and the Altai Republic. And I flew to the Samara region, distributed books, flew to Tyumen – there I took books and military units, abandoned deep in the birch, where no human foot does not step. Then he called me as a military officer: “Come, we do not let anyone – here the subberezoviki sloshing carpet, come, pick up mushrooms!”

Then I flew late in the evening to Novosibirsk to go to the Altai Republic. Why Novosibirsk and not Barnaul? Barnaul did not accept military aircraft. This was my third item and I had the last third of my cargo on board – 300 kg. From this it is clear that I could only work with the military board, the Ministry of Defense. I was met by the government GAZ, and I drove all night – 9 hours – to the Altai Mountains.

Satarov warned me: “Keep in mind, Marietta Omarovna, that your position as a member of the Presidential Council is higher than that of governors.” I say, “I don’t care, I always behave the same way, I can’t blow my cheeks.” But there, in front of me, the chairman of the local government moved also because I noticed that there were only red flags on the city square; everyone in the government was for Zyuganov, but they had to disguise themselves as Yeltsin. All were Stalinists (the farther to the outback, the more it was).

So we are sitting with the then Prime Minister, discussing the protocol of my stay in the Republic. Suddenly the door opens, the young man’s desperate face appears: “Are you a member of the Presidential Council?” Seventy Afghans are waiting for you! And this one, Petrov, shouted at him: "Andrey, go, we are not doing this here, we are drawing up a protocol!" I looked at the desperate eyes of a young man (who was the chairman of the Independent Union of Afghan Veterans), understood everything in a second and said: “Andrey, sit in the corridor and wait: we will draw up a schedule, and I will certainly meet with your Afghans today.” The Prime Minister did not want me to meet with the Afghans, but he could not go against me. He slammed the door, waited, and then drove me. So I met Andrey Mosin, with whom we have been traveling around the country for twenty years. I later learned that he was the best scout in the 40th Army in Afghanistan.

The Union had its own room at the time. When we arrived, we could not enter there, we could suffocate, so smoked, and already they drank, of course (waited for an hour and a half). Hands on the table with clenched fists...

Their first words were: “Marietta Omarovna, are you a member of the Presidential Council?” There's only commies in the government! Give us the vending machines, we'll cut them, and it's over.

When I got home and told my husband, he was horrified: “I can’t imagine what you could say to them?” I said, "Yes, I answered perfectly: "Guys, do you have the Supreme Commander-in-Chief?" - "Of course - Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin!" When the Commander-in-Chief tells you to take the machines, you will take them! In the meantime, only in a peaceful way! And she banged her fist on the table for persuasiveness. And they calmed down, these words worked for them.

Then they tell me: “You don’t go with the government – they will show you Potemkin villages, come with us.” And for three days I drove around the Altai Republic in their cars with prepared sets of books for schools. I barely slept; we went to forty schools. If I had slept, we would have traveled half as much. There is only a car, there is no railway. The farthest area, Kosh Agach, in the 300s, seems to be kilometers from the capital. City one is the capital. And just sat down.

But I saw some amazing things (I'm sure every city, if not every school, has a very good dictionary, at least one): teachers took books and pressed them to their chests, tears on the cheeks of the lyricists are real:

“My God, I don’t believe what Mandelstam has in my hands! I can't believe I'm holding Akhmatova! That I can teach Pasternak from books, not from university notebooks! It was something incredible.

I sat with them in the teacher’s room and talked. It was the 96th year, they were not paid salaries for months, there were no textbooks, notebooks. And they told how the school started a new course, what a teacher dreamed of all his life - embroidery of a special type or lace, as introduced on their own initiative different classes - both mental and manual. They were delayed. And I asked them the same question everywhere, in all forty schools: Imagine that from tomorrow everything comes back to normal: you will have on time salaries, textbooks and notebooks you will be provided, but no extra electives, one program for the whole country and just like before, you write a report monthly headmaster, headmaster in RONO, RONO in GORONO ... What would you choose? I was no boss, I explained that I am on a voluntary basis, from the Presidential Council, their life does not depend on me. And everyone, absolutely everyone, after a little thought, answered that no, still no. They didn't want to come back. Here is the answer about Soviet power and attitude towards it. I saw it in the most difficult time (in Moscow everything was already arranged, and they had it).

After I saw the impact of these deliveries on teachers, school librarians, I knew that this had to continue. And I started thinking about how to do that.

Books for teenagers for their money

Eight or nine years ago, one project was formed: professors-historians, teachers of the Higher School of Economics and History Department of Moscow State University, realized that now the most difficult time for teaching history at school is the nineties. So they decided to help the teachers and published four thin books in one design – the project “Lessons of the nineties”, “Book for a teacher”. And I redirected them from teachers to librarians. I was sure that twenty out of a hundred teachers would use these kits, and the other eighty would lie dead in their homes, not distributing them indiscriminately to all teachers, but giving them to libraries. There is only one teacher who wants to use this book.

I started carting books to local libraries, but of course I didn't want to bring them just these books, because their needs were broader. About me learned Chukovsky’s granddaughter (now, unfortunately, the deceased), Elena Tsesarevna, his main heiress, said that she from each edition brought copies, and she will be happy with my help to give them to Russian libraries. Each time before the next trip, I received a suitcase of such beautifully published “cockroaches” and “Moidodyrov” that I myself would read. Now the Chukovsky family continues this.

There is much that can be done in Russia, the country is big, there are many kind and active people, only we are all poorly connected.

The literary agency that worked with Chukovsky’s books also decided to give us books, including translated literature – Hemingway, Dreiser, Fitzgerald – the sixth or seventh edition, and the heirs of the translators, of course, do not take them anymore. From time to time, Tatiana Sokolova, the head of the agency, calls me and says: I have collected books for you, three boxes. They are brought to my small apartment, I scatter all this along the corridor, I lay it out in several suitcases, because I usually travel to two places: I try effectively, but there is no time, I have to do my science.

A wonderful man, an old man already, the son of the well-known Alexander Volkov (“The Wizard of the Emerald City”), and says: “I know this name – Marietta Chudakova, I trust her, I will pass on books to her, just don’t tell anyone that everyone doesn’t bother me.” And he gives me wonderful books Volkov: and “Yellow fog” (I myself did not know – very much loved “The Wizard of the Emerald City”, and this was after my childhood), “The Secret of an abandoned castle”.

But this is not enough, I still buy: freshly published, and their books are not scientific, those, I believe, who needs – he will buy himself, and I wrote a number of books for teenagers: for that they wrote them, so that they reached teenagers, and I see no other way than to buy and deliver, because not all libraries have money, and most importantly – they are not allowed to choose the right literature.

A few years ago, I wrote a biographical novel for teenagers. She wrote on the countertitle: “For intelligent people from 10 to 16 years old”, the book is called “Egor” – about Yegor Gaidar, today it is the third edition. My principle: not to take a ruble from the publishing house for it – I wrote it for purely moral reasons, to restore justice, because to pour slush on such a beautiful person who, one might say, gave his life to his country in difficult years – is deeply unfair and a bad example for children. And I carried about two thousand books around Russia, to city and school libraries, for my own money.

Librarians love my book Not for Adults. Although I wrote it for teenagers, they say, “Well, we give them our explanations, for us this is a recommendation bibliography.” I write essays, they came out in small books: “Shelf One”, “Shelf Two”, and then the publishing house collected a full book, a three-volume, and already three copies, and there are about the best masterpieces of world literature for children.

Twelve years is a very serious age.

I believe that there are no books of world classics that are too early to read, I am a categorical opponent of these “6+”, “12+” – it is unreasonable, because an intelligent child should be ahead of his age, that is the whole point – he should reach out to a book that he is still too early: what is wrong if an eight-year-old child flips through Anna Karenina? He'll see it, he'll see it's grown-up, he'll shrug his shoulders, but he'll remember it and then he'll turn to it. So, There are no books, I write, that are read early, except those that should never be read..

The second law I came up with: There are books that are too late to read.. Anyone will agree with me, no great mind is needed here to understand that if we did not read Tom Sawyer at twelve years old, then, as people say, “we did not soap” – to sit down to read for the first time in forty years! Here you can re-read, remembering childhood impressions, with great pleasure, in the summer in a hammock. But hardly anyone will even be the same Gulliver, Robinson for the first time read in forty years.

I wrote a detective story for teenagers “The Cases and Horrors of Zhenya Osinkina”. The whole detective part is based on real material, which I am too familiar with, because I read, seven years working in the Commission on pardons – was such under President Yeltsin, over the years – I am afraid to say this figure – tens of thousands of sentences.

For example, in my story there is a boy, Vitek, who served three and a half instead of seven – came out on the presidential decree on pardon, he is older than the other heroes. It is based on a very real story that I met in one sentence: adults, twenty-two to twenty-three years old, decided to steal a motorcycle from tourists and ride it, and then return it. A fourteen-year-old boy was put on the scene. And this boy heard screams downstairs, and when he came down, there were already two dead bodies there, because the tourists didn't want to give up the bike. And the villagers did not intend to kill anyone, but there is always a great danger in breaking the law and normal life, which is what I am trying to express in this book. As a result, they blamed it on him that it was almost him, and this boy thundered into the camp for seven years, because he turned fourteen the day before. Although our criminal liability begins at the age of sixteen, but for serious crimes, murders – sorry, from fourteen.

I had an argument at the committee on the subject. The men said he had to leave the crime scene immediately, go to the police and report what he saw. I say: what are you saying, he would not have gone there, he was the main witness: the same guys who were on good terms with him, but when it comes to murders, they would have sewn him on the way. He couldn't do anything. So I told this story in the book.

My main character, Wife, is twelve years old. Some thought it was not enough for such meaningful action. I remember myself very well at that age – it is a very meaningful age, very serious. At the age of twelve, I made some important decisions that I still follow. One of them saved my life this summer.

I decided, no matter what, to exercise every morning. I generally loved sports, was a grader in rhythmic gymnastics already in my graduate years, in general I took sports seriously since childhood, and then maybe my husband influenced (he was in the top ten at our university in swimming), I loved running on skis, and now I run. And I’ve been doing my exercise for countless years — five, six minutes, five, six exercises, no more time, but I can’t sit down to drink coffee without doing it. So, in the summer, I was hit in my yard by a car going in reverse. The blow was very strong, but there were no fractures - only bruises. And the doctor, convinced of this, said that the role of the shock absorber played a muscle corset.

At the age of twelve, I was taking my sister (she is five years younger than me) from Gagra to Moscow, my mother put us on a train (and then it went three days): she was still there, and the elders were supposed to meet us, but did not meet, a mistake happened, and I drove myself from the Kursk railway station to Sokolnikov with suitcases and a little sister. My mother had no doubt that all three days will be fine and I will take her.

The family album opened with a photo of his grandfather, a royal officer.

My grandfather, a native of Dagestan, was a royal officer. In 1917, he told his eldest son, my father: “The Tsar has abdicated, my oath has been lifted – your fate is now in your hands, you can act as you see fit.”

And so it happened that the Pope got into the civil war in the partisan detachment. He wasn't going to be red, it happened: there were national riots, they wanted independence, and there was some communist clever or clever, and he explained to my father that he was not really against the Russians, but against the White Guards. At the age of eighteen, his father became fascinated by the idea of social justice, became a commander of a partisan detachment in Dagestan, joined the party at the age of twenty, then entered the Timiryazev Academy, became an engineer, worked in the fishing industry - designed purse seines, married my mother, a student. Then he went to work in his republic, but this is a special story - he had to take my mother with three children back to Moscow, because my mother could not get rid of tropical malaria, and the doctor said: "You see, we do not work, Dagestanis have immunity, and the Russians are sick: leave, otherwise you will lose your wife."

And he went to Moscow, and two years later, terror began in his homeland. It began with his uncle, one of the then Dagestani People's Commissars and a member of the Central Committee. They killed all the men with his last name, Khan-Magomedov, every one of them.

My grandfather was arrested in 1937, and my father thought it was a tragic mistake. But, as a communist, he believed his party – he believed that if the sentence said “ten years without the right to correspond” – it means that his father is somewhere in the camp. He didn't know it meant a shooting. In 1956, he was given a rehabilitation letter with the words that his father died in 1942 in the camp from pneumonia. My father, though by no means a fool, believed again: understandably a southerner, fell ill with pneumonia and died.

Years after my father’s death, when I was already a member of the Presidential Council, I wrote out the investigation file of my grandfather from Makhachkala and learned that he had been shot two months after his arrest. But – in a rare case – there are protocols of interrogations, each page is signed: he did not agree with anything, took nothing upon himself, denied everything that was lied to him, and everywhere signed with a firm hand. I’ve seen a lot of cases in the FSB archive, and you can always see how page after page of handwriting is completely changed from torture. My grandfather lasted until the end.

We have known for a long time that we took it only on the spot, and if a person lived in another city or in another region, they did not look for him there, they just did not have personnel for this. But we know it retrospectively, and then we didn’t know it at all!

And my father, after the war, when a new wave of arrests and shootings began, undoubtedly waited every day - like the son of an enemy of the people. And I'm amazed and amazed that there was no atmosphere of fear at home. We knew that our father was not afraid of anyone.

There was even material proof of this – our family album of my childhood opened invariably (and even the elders remembered it before the war) with a photograph of an officer grandfather in uniform among his family. And my father never took it out! And people didn’t just destroy the photos, they destroyed the ashes.

Of the three hundred returned one...

The father volunteered to the front, leaving four children and his wife, pregnant fifth, went through the war as a private. And then my brother left, born in 1925, at the conscription – for two months he was trained as a junior lieutenant near Moscow.

My father returned immediately after the victory over Germany at the end of June, and I will never forget that moment. We are waiting for him this day or tomorrow. I stand in the yard with my sister, whom he has not seen (she is three and a half years old), and I shout to my mother: “Mommy, mommy, just entered the porch of my uncle, very similar to our dad.” My mother, of course, had no doubt that I recognized my father-Dagestani, she shouts from the fourth floor: “So run after him!” And we run, I drag my sister so that she does not fall, run into our damp dark entrance and stop stupefying (I will die, I will not forget) – I hear an incredible female cry, and it comes to me that my mother screams – as they shout at the dead in Russian villages, utterly. She met her father, after four years of war, there on our fourth floor, where he took off in two minutes without an elevator.

And then it was even more interesting, like literature. We had two rooms in a communal apartment, they went to their room, locked themselves in, and then she went out to my son (my second older brother, the famous art historian Selim Omarovich Khan-Magomedov, the world’s best specialist in constructivism) and said: “Look, I don’t know what to do.”

We had on the floor a completely wiped palace once sent from Dagestan, and my father, without taking off his boot, lay down on this palace with the words: “Oh, I am tired.” I fell asleep.

She says to her son, What should I do? He's been sleeping like that for hours, maybe waking up? - "Mama, let her sleep." He slept a day. On the floor, naked, in boots. This is Vanshenkin’s amazing poem: “Everyone slept, and Stalin could not reach Zhukov.”

The older brother returned in late September and early October after defeating Japan, like all the officers. He found his comrade, I still remember his surname, Zaitsev, and together they went to the military enlistment office: “Tell me, which of our comrades born in 1925, who were called up at the same time with us from the Sokolniki military enlistment office, returned?” And they found out that out of three hundred boys, three returned to their mothers. This is a statistic: one out of a hundred. Therefore, who still calls Stalin a great commander? Here it is necessary to remember Viktor Petrovich Astafiev (Kingdom of Heaven, eternal peace), I was friends with him, and he fought the whole war as a private, like my father. In a recent interview, he was asked: “Victor Petrovich, who fought better – the Germans or us?” - "Of course, the Germans." - "How did we win then?" I will never forget the look on his face. - We threw corpses at the Germans.

The justification of tyrants is our shame.It seems to me that people do not realize what year awaits us – the centenary of October. I believe that all educated people should feel their responsibility to the younger generations. Every person with higher education should think about how they will work next year.

If we do not dot the i in the year of the century in the history of the twentieth century, then all adult thinking people – a real shame. For almost thirty years after the end of Soviet power, the most important things have not been done. No one has explained the deepest error of Marxism—we have regarded it as the ultimate truth for almost a century—it turns out that the class struggle is by no means the essence of human life, that the meaning of history is not that the workers take property from the factory owners. No one explained that it is impossible to call a great thinker a man who, like Lenin, made a decisive mental error: he was absolutely sure that the revolution would ignite all over the world after Russia.

And it is time to say that our humanitarian work also has axioms, it is time to introduce them. For example, that October was disastrous for Russia, because it led her from the historical path to the historic stall for more than seventy years, or to the historical dead end – who likes what word better. And those who say, “But how hard was it in the 90s,” we ask the question: we are racing along the highway in a car, suddenly we are stopped: “Where are you going, actually?” - "There it is." “The next dead end, you won’t get there.” - "How do we get there?" But here is a countryside, really, a very bad road, but on it you will get to the goal. Then the question is: continue on the highway or turn on the country road?

I conducted such a test on the topic “What is happening to our teenagers?” with the help of librarians of the Bryansk region, Perm region, Kemerovo and Sverdlovsk regions. The research was this: I asked the children a few questions, and they had to write to their teachers. Why not historians? Because no historian of professional honor will let out of his hands the nonsense that his children will write. And the linguists are responsible for Pushkin and Tolstoy, that is another matter.

Everything went well – beautiful in form, terrible in content. The first question is, “What happened in October 1917?” Question: What do you know about Lenin and what do you think about him? What do you know about Stalin and what do you think about him, what do you know about Yeltsin and what do you think about him?

The answers of fourteen-year-old people were a hundred pieces, exceptions - one or two. Lenin was “good, kind, cared about people, created the USSR.” “Yes, he had flaws, some did not like him, others respected him, he sent dissenters to Siberia, there were repressions, but strengthened the USSR, we won the war under him, he was a generalissimo, commander.” Yeltsin – through all the answers to one – “drinked, destroyed the USSR”.

These are all links in one chain. This double, the governor of the Orel region, confident that St. Petersburg was in the XVI century, says that Ivan the Terrible is a great historical figure. He was asked about Stalin: “Stalin is also a great historical figure.” Now wait for the monument to Stalin in Orel - I promise you that.

I went to Orel on purpose and even, trying to stop this madness, made a brochure – I am not a Medievist myself, so the brochure is “Russian Historians about Ivan the Terrible.” In this pamphlet I have shown, with quotes from our best historians, that it was Stalin who had done everything, that he had to find an excuse for terror, and that he exalted Ivan the Terrible. I printed four hundred copies at my own expense, brought them, distributed them there, but apparently there is something missing in our people today... a real charge that does not allow us to justify villains and tyrants.

I think we should all feel the deepest shame that a quarter of a century after Soviet rule, we have busts of Stalin in the European part of the country growing like mushrooms.

History is not driven by a passive majority, but by an active minority. Let them stand, holding hands, and not let it be installed, as in the 70s – at a much worse time! – the students of history, holding hands, did not allow to demolish the chambers of the XVII century in Moscow. I don't understand that, to be honest. We're in our country!

Do many people know that there is a village of Shelanger in the Republic of Mari El? There was a monument to Stalin, five meters. In boots, with an outstretched hand... What will happen to our children? If the adults did, it means the man was good. This bundle remains in force: cruelty, terror can be justified and even bring victory in a war.

I also want to do my scientific work, I study the history of twentieth century literature, I have a separate file in my computer for every year from 1917 to 1990. I would like to sit down and write a conceptual history of twentieth-century Soviet literature. I get distracted all the time. I ask you to help me with a small part of it. Because with the elders who are crazy, and think that everything is right, nothing can be done. But sociologists underestimate this thing: the electorate is a mobile thing: some die, others turn eighteen. We should think about renewing the electorate so that those who enter are smarter than their parents.

Children should know that there were cannibals in our history.

Many believe that children can not talk about repression – they will not love their homeland. And I am absolutely sure that if you do not instill in a child a sense of compassion, until the age of twelve or thirteen, then all is lost. Either he has compassion as a child—animals innocently killed by fellow citizens—or never again, I vouch for it.

Those people who say that history should educate patriotism understand patriotism as a passive feeling: I sit and admire, as on the screen, my history, how Russia was a victorious step from Rurik to Putin, and there was one deviation - in the nineties. Then for some reason they strayed, and everything was so good. A patriotic feeling cannot be passive; it is good only when it is active. Emphases should be rearranged: not “look what a good story we have”, but what among the beautiful pages were terrible – and it depends on you (we are addressing schoolchildren) that they do not happen again! Only effective patriotism and nothing more.

Why not talk about repression? We read children stories about cannibals! And they see that the cannibal is bad. Let them know we had cannibals and they were bad.

This can be explained from early childhood.

Should teenagers read camp memories? Absolutely. I will tell you about one amazing writer, whom no one knows, whose three books I and the head of the historical and literary society “Return” Semyon Vilensky published a long time ago – Georgy Demidov. He is equal in talent to Shalamov, he is the same Kolymman as that. Shalamov, who spoke a kind word about few, wrote in a notebook: “I have never met a person more intelligent and honest than someone Demidov.” An amazing writer.

Semyon Vilensky had a plan to publish in the series “Memoria” the best samples of prose and memoirs about the Gulag. For the eight books in this series, I have written, at his urging, a preface. For example, one of the authors of the series is Olga Adamova-Sliozberg. Her book is published for the third time, and she should be in every school. When you read it, it becomes so clear – to anyone, I think! – Stalin’s time.

She talks about a woman sitting with her in a cell. She has a twelve-year-old son at home. He writes letters to her. He is not happy with one aunt, on the other, he dreams when his mother returns. She says that now the deadline is over, a little more patience. On June 22, 1941, she was released. And an unspoken order: do not release anyone who has expired until a special order. She writes to her son about it. A month and a half later, he wrote to her, Why don’t you write to me? She goes to her boss and says, Your letter is delayed.

A few months later, a letter comes from a stranger: you, apparently, freed yourself and took up your life, and I found your son with a high temperature at some station in Siberia – the boy went to look for his mother. He lives with me now, but what's next?

A few more years pass and she meets her son in a felony camp.

When I worked on the pardon commission (I was the only woman there in recent years) and spoke out in favor of procrastination, the men sometimes objected: what, he has such a bouquet! And I said (the cases were at hand, lying on the windowsill): Show me his first sentence. And I always saw what I thought it would be: 1945-1947. Fourteen, sixteen-year-old boy, it's clear that his parents are there, and he's sitting down for stealing, and then it goes on, and he's got five or six landings.

Tell the boy that everything depends on him!

Patriotism should be brought up on the pure truth, calling children to act, and I am sure that we ourselves stifle in children activity, their natural property. If you meet a twelve-year-old boy somewhere in a deserted place, and tell him: “Only you can help me, I rely only on you!” – he will help you no worse, or perhaps better than an adult. All he has to do is make sure that a grown woman doesn't fool him, and she really needs his help. He'll come out of his skin and help you. We must appeal to an active sense of patriotism: “The fate of the country depends on you!”

What do they hear in their families now? In 2007, we drove the whole country from Vladivostok to Moscow with Andrey Mosin, an “Afghan” – he is driving – and visited seventeen cities and towns. Everywhere I gave books and had a conversation called “The Modern Literary Situation” – what to read in this sea of books. Both librarians and readers had a great interest, but at the end of the day, a purely public conversation always began: I, a Muscovite, was asked questions.

Seventeen cities and towns, at least two auditoriums in each fifty people. And there was no audience – understand! – in which a man would not stand up (and I, excuse me, an anti-feminist, I believe that the Almighty knew what he did when he divided humanity into men and women, besides living in a greenhouse environment as a child, surrounded by real men – a father and two older brothers, they were not afraid of anyone, so when I look at the current weaklings, I can not imagine that they are men, I consider courage, like the mind – the secondary sexual characteristics of a man) and – according to Nekrasov – breeding hopelessly (as if the director said nothing from me): “So it does not depend on us!”

And when Andrey and I got to Moscow, I said to him, “Well, you know what the most common phrase in Russia is?” “Yes,” he says, “I understand everything.” I swear to you, there were no exceptions.

Every family has grown-up dads and moms and they say to each other, ‘Well, you know, it doesn’t matter.’

My opinion (those who have boys, children or grandchildren, nephews, those with me, I think, will agree): if at the age of twelve a boy is instilled that nothing depends on him, he will not be needed in the future by his wife, or an old mother, or, excuse me for his high-mindedness, the Motherland. A boy at twelve must be sure that everything depends on him. Let him be disappointed later. The boy should be encouraged that he can do anything, everything depends on him, and his homeland is waiting for him.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: www.pravmir.ru/marietta-chudakova-ya-dostavlyala-knigi-voennyim-bortom/

Bertrand Russell: the older I get, the longer be periods of happiness

How to read a cholesterol test