534

Why do we always get sick in the winter?

It begins with leaf fall. The mercury is falling, the sunlight fades and there comes a cough. In the best case, in the form of the common cold, which leaves a strange feeling fighting throat.

If you are unlucky, the body encompasses a high temperature and aches in the limbs for up to a week or more. Flu.

The flu season is a fact of life, but until recently no one knew why. The answer lies in the disgusting ways in which people share their germs among themselves.

The flu season appears so predictable and affects so many people that it is hard to believe that scientists have no idea why the cold weather associated with the spread of germs. But over the last five years, they, however, reached a number of conclusions that can give us the answer and help stem the tide of infection — and they are all hovering around the gloomy fact about what comes out of your lungs in the air in the process of sneezing.

A new understanding of flu may not come fast enough; worldwide up to five million people suffer from the flu each season and about a quarter of a million die from it. Part of the problem is that the virus changes so quickly that the human body does not have time to prepare for the strain of the new season. "The antibodies that we generated, don't recognize the virus — so we are losing immunity," says Jane Metz of the University of Bristol. It also complicates the development of effective vaccines. In addition, it comes in basic ignorance: even if you create a new vaccine for each strain, try to convince people to accept it.

It is hoped that a better understanding of why flu spreads in winter, but naturally disappears in the summer, will help doctors to find simple ways to stop its spread. Previous theories have relied on our behavior. We spend more time indoors in winter, and hence are in close contact with other people who may be carriers of the bacteria. Also we are likely going to use public transport — and when we pressed the sneezing passengers, and the Windows is the condensation of their cough, it's easy to assume that at some time the flu gets to the us.

Another popular idea hovering around our physiology: cold weather reduces the defence ability of your organism against infections. In the short winter days, without abundant sunlight, we suffer from a lack of vitamin D, which helps the immune system, making us more vulnerable to infection. In addition, when we inhale cold air, blood vessels in the nose constrict to prevent heat loss. It can inhibit white blood cells (fighters against microbes) of our mucous membranes and eradicate all the viruses that we breathe, allowing them to freely pass through our defense. (That's partly why, perhaps, we tend to get sick, leaving the house with a wet head).

Although such factors will play a role in the transmission of influenza, the analysis shows that they cannot fully explain the onset of the annual flu season. Instead, the answer may be hiding in the invisible air we breathe. Thanks to the laws of thermodynamics, the cold air can carry less water vapor until it reaches the "point of condensation" and shed the rain. Therefore, even though the weather outside may appear wet, the air is dry because it loses moisture. Studies over the last few years have shown that these dry conditions provide the ideal environment for the spread of the flu virus.

Laboratory experiments have shown how the flu spreads among groups of Guinea pigs. In humid air, the epidemic can not build momentum, whereas in dry conditions it spread like wildfire. Comparing climate records over 30 years with records of public health Jeffrey Shaman of Columbia University and his colleagues found that flu epidemics almost always follow a fall in humidity. The charts overlap so closely that "you can almost overlay one on the other," says Metz. Discovery scientists repeatedly reproduced, even including the analysis of swine flu pandemic in 2009.

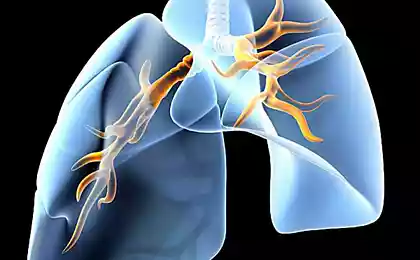

It's counterintuitive because we usually think that the wet weather makes it worse, and does not protect us from disease. But to understand why, you need to understand the peculiar dynamics of our cough and sneeze. Every time we have a cold and sneeze, we release a mist of particles from our nose and mouth. In humid air, these particles can be relatively large and fall to the floor. But in dry air they are broken down into smaller particles become so small that they can stay afloat for hours or days. A suspension is formed. As a result, in winter, you breathe a cocktail of dead cells, mucus and viruses all of you who have recently visited the room.

Moreover, the water vapor in the air seems to be toxic to the virus. Perhaps changing the acidity or salt concentration in the shreds of mucus, moist air can damage the surface of the virus, thereby destroying the weapon, which allows him to attack our cells. In contrast, viruses in dry air can float around and stay active for hours — until they don't breathe or swallow, and allowed him to settle on the cells of the throat.

From any rule there are exceptions. Although the air on planes, as a rule, dry, it didn't seem to increase the risk of catching the flu — perhaps because of air conditioning filters out any bacteria before they have time to spread. Although dry air seem to contribute to the spread of influenza in temperate regions of Europe and North America, some contradictory results indicate that microbes behave similarly in tropical regions.

One explanation implies that in particularly warm and humid tropical climates the virus can eventually settle on large surfaces in the room. Thus, although it is poorly survives in the air, he thrives on everything that you touch, and after penetrates in her mouth.

Well, let's say, all right. But while these findings might suggest a simple way of killing all the bacteria while they are in the air, at least in the Northern regions. Tyler Kep from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, estimate that the performance of the humidifier in the school for one hour can kill about 30% of all viruses, flying in the air. The same steps (almost literally) can throw cold water on other hot spots for the spread of disease — like corridors in hospitals or public transport.

"Thus it will be possible to curb a major outbreak, which occur every couple of years with the change of the influenza virus, he says. — Potential exhaust in the cost of missed work days, school days, in terms of health, will be enormous."

The shaman is now considering further action, although it believes that it will not be easy.

"Although high humidity is associated with low levels of survival of the flu, there are other pathogens like mold, which thrive in high humidity, he says. — So the moisture will have to be approached with caution".

Scientists emphasize that vaccination and good personal hygiene are still the best ways to protect yourself; use of steam for killing germs is just a suggestion, the second line of attack. When dealing with such a slippery and ubiquitous enemy, as the flu virus, it is necessary to use all possible weapons in the Arsenal.published

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! © Join us at Facebook , Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: hi-news.ru

If you are unlucky, the body encompasses a high temperature and aches in the limbs for up to a week or more. Flu.

The flu season is a fact of life, but until recently no one knew why. The answer lies in the disgusting ways in which people share their germs among themselves.

The flu season appears so predictable and affects so many people that it is hard to believe that scientists have no idea why the cold weather associated with the spread of germs. But over the last five years, they, however, reached a number of conclusions that can give us the answer and help stem the tide of infection — and they are all hovering around the gloomy fact about what comes out of your lungs in the air in the process of sneezing.

A new understanding of flu may not come fast enough; worldwide up to five million people suffer from the flu each season and about a quarter of a million die from it. Part of the problem is that the virus changes so quickly that the human body does not have time to prepare for the strain of the new season. "The antibodies that we generated, don't recognize the virus — so we are losing immunity," says Jane Metz of the University of Bristol. It also complicates the development of effective vaccines. In addition, it comes in basic ignorance: even if you create a new vaccine for each strain, try to convince people to accept it.

It is hoped that a better understanding of why flu spreads in winter, but naturally disappears in the summer, will help doctors to find simple ways to stop its spread. Previous theories have relied on our behavior. We spend more time indoors in winter, and hence are in close contact with other people who may be carriers of the bacteria. Also we are likely going to use public transport — and when we pressed the sneezing passengers, and the Windows is the condensation of their cough, it's easy to assume that at some time the flu gets to the us.

Another popular idea hovering around our physiology: cold weather reduces the defence ability of your organism against infections. In the short winter days, without abundant sunlight, we suffer from a lack of vitamin D, which helps the immune system, making us more vulnerable to infection. In addition, when we inhale cold air, blood vessels in the nose constrict to prevent heat loss. It can inhibit white blood cells (fighters against microbes) of our mucous membranes and eradicate all the viruses that we breathe, allowing them to freely pass through our defense. (That's partly why, perhaps, we tend to get sick, leaving the house with a wet head).

Although such factors will play a role in the transmission of influenza, the analysis shows that they cannot fully explain the onset of the annual flu season. Instead, the answer may be hiding in the invisible air we breathe. Thanks to the laws of thermodynamics, the cold air can carry less water vapor until it reaches the "point of condensation" and shed the rain. Therefore, even though the weather outside may appear wet, the air is dry because it loses moisture. Studies over the last few years have shown that these dry conditions provide the ideal environment for the spread of the flu virus.

Laboratory experiments have shown how the flu spreads among groups of Guinea pigs. In humid air, the epidemic can not build momentum, whereas in dry conditions it spread like wildfire. Comparing climate records over 30 years with records of public health Jeffrey Shaman of Columbia University and his colleagues found that flu epidemics almost always follow a fall in humidity. The charts overlap so closely that "you can almost overlay one on the other," says Metz. Discovery scientists repeatedly reproduced, even including the analysis of swine flu pandemic in 2009.

It's counterintuitive because we usually think that the wet weather makes it worse, and does not protect us from disease. But to understand why, you need to understand the peculiar dynamics of our cough and sneeze. Every time we have a cold and sneeze, we release a mist of particles from our nose and mouth. In humid air, these particles can be relatively large and fall to the floor. But in dry air they are broken down into smaller particles become so small that they can stay afloat for hours or days. A suspension is formed. As a result, in winter, you breathe a cocktail of dead cells, mucus and viruses all of you who have recently visited the room.

Moreover, the water vapor in the air seems to be toxic to the virus. Perhaps changing the acidity or salt concentration in the shreds of mucus, moist air can damage the surface of the virus, thereby destroying the weapon, which allows him to attack our cells. In contrast, viruses in dry air can float around and stay active for hours — until they don't breathe or swallow, and allowed him to settle on the cells of the throat.

From any rule there are exceptions. Although the air on planes, as a rule, dry, it didn't seem to increase the risk of catching the flu — perhaps because of air conditioning filters out any bacteria before they have time to spread. Although dry air seem to contribute to the spread of influenza in temperate regions of Europe and North America, some contradictory results indicate that microbes behave similarly in tropical regions.

One explanation implies that in particularly warm and humid tropical climates the virus can eventually settle on large surfaces in the room. Thus, although it is poorly survives in the air, he thrives on everything that you touch, and after penetrates in her mouth.

Well, let's say, all right. But while these findings might suggest a simple way of killing all the bacteria while they are in the air, at least in the Northern regions. Tyler Kep from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, estimate that the performance of the humidifier in the school for one hour can kill about 30% of all viruses, flying in the air. The same steps (almost literally) can throw cold water on other hot spots for the spread of disease — like corridors in hospitals or public transport.

"Thus it will be possible to curb a major outbreak, which occur every couple of years with the change of the influenza virus, he says. — Potential exhaust in the cost of missed work days, school days, in terms of health, will be enormous."

The shaman is now considering further action, although it believes that it will not be easy.

"Although high humidity is associated with low levels of survival of the flu, there are other pathogens like mold, which thrive in high humidity, he says. — So the moisture will have to be approached with caution".

Scientists emphasize that vaccination and good personal hygiene are still the best ways to protect yourself; use of steam for killing germs is just a suggestion, the second line of attack. When dealing with such a slippery and ubiquitous enemy, as the flu virus, it is necessary to use all possible weapons in the Arsenal.published

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! © Join us at Facebook , Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: hi-news.ru