375

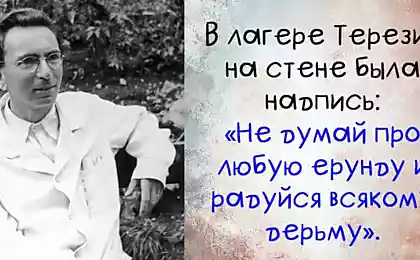

Victor Frankl on Internal Freedom

Every time on the eve of May 9, restless minds try to re-understand and rethink what happened to humanity in the middle of the last century.How in our “civilized world” could fascism and gas chambers appear, in what corners of the soul of “normal people” hides a beast capable of coldly and cruelly killing his own kind, where people could draw strength to survive in inhuman conditions of war and concentration camps?

After all, May 9 is always a reason to think about the main question:Have we learned the lessons of that war? I don't think so.Nevertheless, today I want to do without pathetic words and edifying descriptions of the horrors that took place in the 40s of the last century on our planet. Instead, we decided to publish a few quotes.From the greatest book of the XX century “Say life Yes!” Psychologist in a concentration campIt was written by the brilliant psychologist Victor Frankl, who lost his entire family and went through several concentration camps during World War II.

Why this particular book? BecauseIt is much broader than any question of war and peace, it is about man and his eternal striving for meaning, even where it would seem that this meaning cannot exist.. It is about how a person can always remain human and not depend on conditions, however cruel and unjust they may be.

Nearly in the middle of his life is a rift marked by the dates 1942-1945. These are Frankl’s years in Nazi concentration camps, an inhuman existence with a tiny chance of surviving.

Almost anyone who is lucky enough to survive would consider it the greatest happiness to erase these years from life and forget them as a terrible dream. But on the eve of the war, Frankl basically completed the development of his theory of the desire for meaning as the main driving force of behavior and personality development. And in the concentration camp, this theory received unprecedented life test and confirmation.According to Frankl, the greatest chances of survival were not those who were in the best health, but those who were in the strongest spirit, who had meaning, for which to live.. Few people in the history of mankind have paid such a high price for their convictions and whose views have been so severely tested. Victor Frankl is on a par with Socrates and Giordano Bruno, who died for the truth.

Dmitri Leontiev, MD

In the book, Frankl describes his own experience of survival in a concentration camp, analyzes the state of himself and the rest of the prisoners from the point of view of a psychiatrist, and outlines his psychotherapeutic method of finding meaning in all aspects of life, even the most terrible.

It is extremely gloomy and at the same time the brightest hymn to a man who has ever existed on earth.To say that this is a panacea for all the problems of mankind, of course, it is impossible, but anyone who has ever wondered about the meaning of their existence and the injustice of the world will find in the book "Say Life Yes!". A psychologist in a concentration camp, answers with which it will be difficult to argue. What does this phrase cost?

A person should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather should realize that he is the one to whom this question is addressed.

We highly recommend reading Frankl's entire work (this world-famous book is no more than two hundred pages), but if you don't have time for it, here are a few fragments from there.

A book

“A Psychologist in a Concentration Camp” is the subtitle of this book. This is more about experiences than about real events. The purpose of the book is to reveal the experiences of millions of people. This is a concentration camp seen from the inside, from the perspective of a person who has personally experienced everything that will be told here. Moreover, we will not talk about the global horrors of concentration camps, about which much has already been said (horrors so incredible that not even everyone believed in them and not everywhere), but about the endless “small” tortures that the prisoner experienced every day. About how this painful camp everyday life affected the state of mind of the average prisoner.

From camp life

If we try, at least in a first approximation, to organize the huge material of our own and others' observations made in concentration camps, to bring it into some system, then in the psychological reactions of prisoners we can distinguish three phases: arrival in the camp, stay in it and release.

<...>

The first phase can be described as an “arrival shock”, although, of course, the psychological shock of a concentration camp can precede the actual entry into it.

<...>

Psychiatrists know the picture of the so-called delirium of pardon, when a sentenced to death literally before execution begins, in complete madness, to believe that at the very last moment he will be pardoned.

So we were enlightened with hope and believed that it would not be, could not be so terrible. Well, look at these red-faced types, these glossy cheeks! What we did not know at the time was that it was the camp elite, people specially selected to meet the trains that had been arriving at Auschwitz every day for years. And, encouraging the newcomers with their appearance, take their luggage with all the valuables that may be hidden in it - some rare thing, jewelry.

By that time, that is, by the middle of the Second World War, Auschwitz had become the center of Europe. Here a huge amount of valuables – gold, silver, platinum, diamonds, and not only in the shops, but also in the hands of the SS, and even some members of the special group that met us.

<...>

There are still naive people among us (to the amusement of helpers from among the “old” campers) asking whether it is possible to keep a wedding ring, a medallion, some memorabilia, a talisman: no one can yet believe that literally everything is taken away.

I try to trust one of the old campers, lean over to him and, showing the paper bundle in the inner pocket of my coat, say, "Look, I have here a manuscript of a scientific book." I know what you will say, I know that to stay alive, only alive, is the greatest thing you can ask of fate. But I can't help it, I'm so crazy, I want more. I want to keep this manuscript, hide it somewhere, it's my life's work. He seems to be beginning to understand me, he chuckles, at first rather sympathetic, then more ironically, contemptuously, mockingly, and finally, with a grimace of utter neglect, he roars maliciously at me in response to the only word, the most popular word in the vocabulary of prisoners: "Shit!"

Now I have finally learned how things are. And what happens to me is what you might call the peak of the first phase of psychological reactions:I draw a line under all my former life.

On psychological reactions

Illusions collapsed, one by one. And then there was something unexpected: black humor. We realized that we had nothing to lose except a ridiculously naked body. Even in the shower, we began to exchange jokes (or pretending to do so) to cheer each other up and above all ourselves. Some reason for this was – after all, water really comes from the taps!

<...>

In addition to black humor, there was another sense of curiosity.

Personally, I was already familiar with this emergency response from a different field. In the mountains, in the collapse, desperately clinging and climbing, I felt for some seconds, even a split second, a kind of detached curiosity: will I live? Get a skull injury? Broken any bones?

And in Auschwitz people for a short time there was a state of objectification, detachment, a moment of almost cold curiosity, almost a sideways observation, when the soul, as it were, turns off and thereby tries to defend itself, to be saved. We were curious about what would happen next. How, for example, will we, completely naked and wet, come out of here in the cold of late autumn?

<...>

The hopelessness of the situation, the daily, hourly, minutely threat of death - all this led almost every one of us, even briefly, to the thought of suicide. But on the basis of my worldview, which will be discussed later, on the first evening, before I fell asleep, I gave myself the word “not to throw myself on the wire.” This specific camp expression denoted the local method of suicide - touching barbed wire, get a fatal shock of high voltage current.

<...>

Within a few days, psychological reactions begin to change. Having experienced the initial shock, the prisoner gradually plunges into the second phase - the phase of relative apathy, when something in his soul dies.

<...>

Apathy, inner stupor, indifference - these manifestations of the second phase of the psychological reactions of the prisoner made him less sensitive to daily, hourly beatings. It is this kind of insensitivity that can be considered the most necessary protective armor, with the help of which the soul tried to protect itself from heavy damage.

<...>

Come back.towardlethargyAs the main symptom of the second phase, it should be said thatThis is a special mechanism of psychological protection.. Reality is narrowing. All thoughts and feelings concentrate on one single task: to survive. And in the evening, when the exhausted people were returning from work, one sentence could be heard from everyone: well, another day is over!

<...>

It is quite understandable, therefore, that in the condition of such a psychological press, and under the pressure of the necessity of concentrating entirely on immediate survival, the whole psychic life was reduced to a rather primitive stage. Psychoanalytically oriented colleagues from among the comrades in misfortune often spoke of the “regression” of man in the camp, of his return to more primitive forms of mental life. This primitiveness of desires and aspirations was clearly reflected in the typical dreams of prisoners.

Humiliation.

The bodily pain inflicted by the beatings was not the most important for us prisoners (just as it was for the punished children).Mental pain, resentment against injustice - that, despite the apathy, tormented more.In this sense, even a blow that comes by can be painful.

Once, for example, we worked in a heavy snowstorm on the railway tracks. At least for the sake of not freezing completely, I very diligently trampled the rut with rubble, but at some point stopped to blow my nose. Unfortunately, it was at this point that the escort turned to me and, of course, decided that I was out of work.

The most painful thing for me in this episode was not the fear of disciplinary action, of beating. Despite the already utter, it would seem, mental stupor, I was extremely hurt that the escort did not consider that miserable creature, as I was in his eyes, worthy of even a swear word: as if playing, he lifted a stone from the ground and threw at me. I should have understood that this attracts the attention of an animal, so the livestock is reminded of its duties - indifferently, without condescending to punishment.

On the inner pillar

Psychological observations have shown that, among other things, the camp environment influenced character changes only in the prisoner who descended spiritually and in a purely human way. And he went down who no longer had any inner support. But now let us ask the question: what could and should have been such a support?

<...>

According to the unanimous opinion of psychologists and prisoners themselves, the man in the concentration camp was most depressing because he did not know at all how long he would be forced to stay there. There was no deadline!

<...>

The Latin word finis has two meanings: end and goal.A man who is unable to foresee the end of this temporary existence cannot thereby direct his life toward any goal.He can no longer, as it is generally characteristic of a person under normal conditions, orient himself to the future, which violates the general structure of his inner life as a whole, deprives him of support.

Similar conditions have been described in other areas, such as the unemployed. They too, in a sense, cannot firmly count on the future, set themselves a definite goal in this future. Among unemployed miners, psychological observations have revealed similar distortions in the perception of that particular time, which psychologists call “internal time” or “time experience.”

<...>

The inner life of the prisoner, who did not rely on the “goal in the future” and therefore descended, acquired the character of a retrospective existence. We have already spoken in another connection about the tendency to return to the past, that such immersion in the past devalues the present with all its horrors.But the devaluation of the present, surrounding reality is fraught with a certain danger - a person ceases to see at least some, even the slightest, possibilities of influencing this reality.But some heroic examples show that even in the camp such opportunities sometimes occurred.

The devaluation of reality, accompanying the “temporary existence” of prisoners, deprived a person of support, forcing him to finally fall down, lose heart – because “all is in vain anyway.”Such people forget that the most difficult situation gives a person the opportunity to rise internally above himself.Instead of viewing the external hardships of camp life as a test of their spiritual fortitude, they treated their present being as something from which to turn their backs, and, having closed themselves, completely immersed themselves in their past. And their lives were in decline.

Of course, few are capable of reaching inner heights amidst the horrors of a concentration camp. But there were. They were able to reach, in an external crash, and even in death, a peak which was unattainable to them in their daily existence.

<...>

It can be said that most of the people in the camp believed that all their possibilities of self-fulfillment were behind them, and yet they were only opening up.For it depended on the man himself whether he would turn his camp life into a vegetation like that of a thousand, or a moral victory like that of a few.

On hope and love

Kilometer by kilometer we walk next to him, drowning in the snow, then sliding on the icy boograms, supporting each other, hearing abuse and whining. We don’t say another word, but we know that each of us is thinking about his wife.

From time to time, I glance at the sky: the stars are already pale, and there, in the distance, the pink light of the morning dawn begins to break through the thick clouds. And before my spiritual gaze is a beloved man. My imagination managed to embody it so vividly, as vividly as it had never been in my previous, normal life. I talk to my wife, I ask questions, she answers. I see her smile, her cheering gaze, and—though this gaze is incorporeal—it shines brighter for me than the rising sun.

<...>

Suddenly a thought strikes me: for now, for the first time in my life, I have understood the truth of what so many thinkers and sages considered their final conclusion, that so many poets chanted: I understood, I accepted the truth.Only love is that finite and supreme which justifies our existence here, which can elevate and strengthen us!Yes, I understand the meaning of the result achieved by human thought, poetry, faith.Liberation - through love, in love!

I now know that a man who has nothing in the world can possess spiritually, even for a moment, the most precious image of the one he loves. In the most difficult of all imaginable difficult situations, when it is no longer possible to express oneself in any action, when the only suffering remains, in such a situation a person can realize himself by recreating and contemplating the image of the one he loves.

For the first time in my life, I was able to understand what is meant by saying that angels are happy with the loving contemplation of the infinite Lord.

<...>

Frozen earth does not lend itself well, solid lumps fly from under the pickaxe, sparks flash. We're not warm yet, we're still silent. And my spirit is again hovering around my beloved. I'm still talking to her, she's still answering me. Suddenly I thought, I don’t even know if she’s alive!

But I now know another thing: the less love is concentrated on the corporeal nature of man, the deeper it penetrates into his spiritual essence, the less essential his “so-being” (as philosophers call it), his “here-being”, “here-with-me-presence”, his corporeal existence in general becomes.

In order to evoke the spiritual image of my beloved now, I do not need to know whether she is alive or not. Had I known at that moment that she was dead, I am sure that in spite of this knowledge, she would still have evoked her spiritual image, and my spiritual dialogue with him would have been just as intense and filled all of me. For I felt at that moment the truth of the words of the Song of Songs:Set me as a seal on your heart, for love is as strong as death.(8:6).

<...>

Listen, Otto! If I don't go home to my wife, and if you see her, you'll tell her, listen carefully! First, we talked about it every day, remember? Second, I didn't love anyone more than her. Thirdly, the short time that we were with her has remained for me such a happiness that outweighs all the bad, even what is to be experienced now.

About inner life

Sensitive people, accustomed from a young age to the predominance of spiritual interests, endured the camp situation, of course, extremely painful, but in the spiritual sense it acted on them less destructively, even with their mild nature. Because they were more accessible.Return from this terrible reality to a world of spiritual freedom and inner riches. It is this and only this that can explain the fact that people of fragile build sometimes better resisted the camp reality than outwardly strong and strong.

<...>

Retirement meant for those who were capable of this, an escape from the joyless desert, from the spiritual poverty of the local existence back to their own past. Fantasy was constantly busy restoring past impressions. And most often these were not some significant events and deep experiences, but details of everyday life, signs of a simple, calm life. In sad memories, they come to the prisoners, bringing them light.

Turning away from the present surrounding him, returning to the past, a person mentally restored some of his reflections, prints. The whole world, the whole past life, was taken away from him, moved far away, and the longing soul rushes after the departed - there, there. Here you go in the tram; here you come home, open the door; here the phone rings, you pick up the phone; you light up the light. Such simple, at first glance ridiculously insignificant details touch, touch to tears.

<...>

Those who retained the capacity for inner life did not lose the ability to perceive the beauty of nature or art at least occasionally, even when the slightest opportunity was given.And the intensity of this experience, even for some moments, helped to disconnect from the horrors of reality, to forget about them.

When we moved from Auschwitz to the Bavarian camp, we looked through barred windows at the peaks of the Salzburg Mountains, illuminated by the setting sun. If anyone had seen our admiring faces at this moment, they would never have believed that they were people whose lives were almost over. And in spite of that -- or precisely because of that? -- we were captivated by the beauty of nature, the beauty from which we had been detached for years.

Happiness

Happiness is when the worst gets by.

<...>

We were grateful for the slightest relief. Some new trouble might have happened, but it didn’t.. We rejoiced, for example, if in the evening, before going to bed, nothing prevented us from destroying lice. Of course, this in itself is not such a pleasure, especially since it was necessary to undress naked in an unheated barracks, where icicles dangled from the ceiling (inside the room!). But we thought we were lucky if there was no air alert and no blackout at that point, which meant that this interrupted activity took us midnight.

<...>

But back to relativity. A long time later, after his release, someone showed me a picture in an illustrated newspaper: a group of concentration camp inmates lying on their high-rise bunks and staring bluntly at the person who was photographing them. "Isn't it terrible - these faces, all this?" they asked me. I wasn't terrified. Because at that moment, I had this picture before me.

Five in the morning. It's still a dark night. I lie on bare boards in the dugout, where almost 70 more comrades are on lightweight mode. We are marked as sick and can not go to work, do not stand in formation on the parade ground. We lie close together, not only because of the cramping, but also to keep the crumbs warm. We are so tired that we do not need to move our arm or leg.

All day, lying down like this, we'll wait for our cut-down portions of bread and watery soup. How happy we are, how happy we are!

Outside, from the end of the parade ground, where the night shift should return, you can hear whistles and sharp screams. The door opens, a snow whirlwind bursts into the dugout and a figure covered with snow appears in it. Our exhausted, barely standing comrade is trying to sit on the edge of the Nar. But the senior in the block pushes him back, because in this dugout is strictly forbidden to enter those who are not on the "light mode".

How sorry I am for this comrade! And how happy I am not to be in his shoes, and to remain in the "light" barracks. And what a salvation - to get in the outpatient camp infirmary "relief" for two, and then, in addition, for two more days! To the typhoid camp?

On personal depreciation

We have already talked about the depreciation to which, with few exceptions, everything that did not directly serve to preserve life has been subjected. And this revision led to the fact that in the end man ceased to value himself, that in the vortex that plunged into the abyss of all former values, the personality was drawn.

Under a certain suggestive influence of that reality, which has long wanted to know nothing about the value of human life, about the significance of the personality, which turns a person into an unrequited object of destruction (previously using, however, the remnants of his physical abilities), under this influence, his own self is ultimately devalued.

<...>

A person who is not able to oppose himself to reality with the last rise of self-esteem generally loses the feeling of himself as a subject in the concentration camp, not to mention the feeling of himself as a spiritual being with a sense of inner freedom and personal value.

He begins to perceive himself rather as a particle of some great mass, his being descends to the level of herd existence. After all, people, regardless of their own thoughts and desires, are driven here and there, alone or all together, like a flock of sheep. Right and left, front and back, you are chased by a small but powerful, armed gang of sadists who, with kicks, kicks, boots, rifle butts, force you to move back and forth.

We have reached the state of a flock of sheep that only know to avoid dog attacks and, when left alone for a moment, eat a little. And like sheep, fearfully straying into a heap at the sight of danger, each of us sought not to remain at the edge, to get into the middle of his row, in the middle of his column, in the head and tail of which there were convoys.

In addition, the place in the center of the column promised some protection from the wind. So that the state of man in the camp, which can be called the desire to dissolve in the general mass, arose not only under the influence of the environment, it was also an impulse of self-preservation. The desire of each to dissolve in the mass was dictated by one of the most important laws of self-preservation in the camp: the main thing is not to stand out, not to attract the attention of the SS for any reason!

<...>

A person lost the feeling of himself as a subject not only because he was completely subject to the arbitrariness of the camp guards, but also because he felt dependence on pure accidents, became a toy of fate. I have always thought and maintained that a person begins to understand why this or that has happened in his life and what has been good for him, only after a while, five or ten years. In the camp, this sometimes became clear after five or ten minutes.

Internal freedom

There are many examples, often truly heroic, that show that you can overcome apathy, curb irritation. That even in this situation, which is absolutely overwhelming both externally and internally, it is possible to preserve the remnants of spiritual freedom, to oppose this pressure with your spiritual self.

Who among the survivors of the concentration camp could not tell about the people who, walking with everyone in the column, passing through the barracks, gave someone a kind word, and with someone shared the last crumbs of bread?

And even if there were few of them, their example confirms that in a concentration camp you can take away everything from a person except the last one - human freedom, freedom to relate to circumstances, or one way or another. And it was “one way or another” they had.

And every day, every hour in the camp gave a thousand opportunities to make this choice, to renounce or not to renounce the most secret that the surrounding reality threatened to take away - from inner freedom. And to renounce freedom and dignity meant to become an object of the influence of external conditions, to allow them to fashion out of you a “typical” camper.

<...>

No, experience confirms that the mental reactions of the prisoner were not just a natural imprint of bodily, mental and social conditions, calorie deficit, lack of sleep and various psychological “complexes”. Ultimately, it turns out:What happens inside a person, what the camp allegedly “makes out of him” is the result of the inner decision of the person himself.. In principle, it depends on each person what, even under the pressure of such terrible circumstances, will happen in the camp with him, with his spiritual, inner essence: whether he will turn into a “typical” camp or remain a person here, preserve his human dignity. published

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: monocler.ru/psiholog-v-kontslagere-viktor-frankl-o-vnutrenney-svobode-i-smyisle-zhizni/

After all, May 9 is always a reason to think about the main question:Have we learned the lessons of that war? I don't think so.Nevertheless, today I want to do without pathetic words and edifying descriptions of the horrors that took place in the 40s of the last century on our planet. Instead, we decided to publish a few quotes.From the greatest book of the XX century “Say life Yes!” Psychologist in a concentration campIt was written by the brilliant psychologist Victor Frankl, who lost his entire family and went through several concentration camps during World War II.

Why this particular book? BecauseIt is much broader than any question of war and peace, it is about man and his eternal striving for meaning, even where it would seem that this meaning cannot exist.. It is about how a person can always remain human and not depend on conditions, however cruel and unjust they may be.

Nearly in the middle of his life is a rift marked by the dates 1942-1945. These are Frankl’s years in Nazi concentration camps, an inhuman existence with a tiny chance of surviving.

Almost anyone who is lucky enough to survive would consider it the greatest happiness to erase these years from life and forget them as a terrible dream. But on the eve of the war, Frankl basically completed the development of his theory of the desire for meaning as the main driving force of behavior and personality development. And in the concentration camp, this theory received unprecedented life test and confirmation.According to Frankl, the greatest chances of survival were not those who were in the best health, but those who were in the strongest spirit, who had meaning, for which to live.. Few people in the history of mankind have paid such a high price for their convictions and whose views have been so severely tested. Victor Frankl is on a par with Socrates and Giordano Bruno, who died for the truth.

Dmitri Leontiev, MD

In the book, Frankl describes his own experience of survival in a concentration camp, analyzes the state of himself and the rest of the prisoners from the point of view of a psychiatrist, and outlines his psychotherapeutic method of finding meaning in all aspects of life, even the most terrible.

It is extremely gloomy and at the same time the brightest hymn to a man who has ever existed on earth.To say that this is a panacea for all the problems of mankind, of course, it is impossible, but anyone who has ever wondered about the meaning of their existence and the injustice of the world will find in the book "Say Life Yes!". A psychologist in a concentration camp, answers with which it will be difficult to argue. What does this phrase cost?

A person should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather should realize that he is the one to whom this question is addressed.

We highly recommend reading Frankl's entire work (this world-famous book is no more than two hundred pages), but if you don't have time for it, here are a few fragments from there.

A book

“A Psychologist in a Concentration Camp” is the subtitle of this book. This is more about experiences than about real events. The purpose of the book is to reveal the experiences of millions of people. This is a concentration camp seen from the inside, from the perspective of a person who has personally experienced everything that will be told here. Moreover, we will not talk about the global horrors of concentration camps, about which much has already been said (horrors so incredible that not even everyone believed in them and not everywhere), but about the endless “small” tortures that the prisoner experienced every day. About how this painful camp everyday life affected the state of mind of the average prisoner.

From camp life

If we try, at least in a first approximation, to organize the huge material of our own and others' observations made in concentration camps, to bring it into some system, then in the psychological reactions of prisoners we can distinguish three phases: arrival in the camp, stay in it and release.

<...>

The first phase can be described as an “arrival shock”, although, of course, the psychological shock of a concentration camp can precede the actual entry into it.

<...>

Psychiatrists know the picture of the so-called delirium of pardon, when a sentenced to death literally before execution begins, in complete madness, to believe that at the very last moment he will be pardoned.

So we were enlightened with hope and believed that it would not be, could not be so terrible. Well, look at these red-faced types, these glossy cheeks! What we did not know at the time was that it was the camp elite, people specially selected to meet the trains that had been arriving at Auschwitz every day for years. And, encouraging the newcomers with their appearance, take their luggage with all the valuables that may be hidden in it - some rare thing, jewelry.

By that time, that is, by the middle of the Second World War, Auschwitz had become the center of Europe. Here a huge amount of valuables – gold, silver, platinum, diamonds, and not only in the shops, but also in the hands of the SS, and even some members of the special group that met us.

<...>

There are still naive people among us (to the amusement of helpers from among the “old” campers) asking whether it is possible to keep a wedding ring, a medallion, some memorabilia, a talisman: no one can yet believe that literally everything is taken away.

I try to trust one of the old campers, lean over to him and, showing the paper bundle in the inner pocket of my coat, say, "Look, I have here a manuscript of a scientific book." I know what you will say, I know that to stay alive, only alive, is the greatest thing you can ask of fate. But I can't help it, I'm so crazy, I want more. I want to keep this manuscript, hide it somewhere, it's my life's work. He seems to be beginning to understand me, he chuckles, at first rather sympathetic, then more ironically, contemptuously, mockingly, and finally, with a grimace of utter neglect, he roars maliciously at me in response to the only word, the most popular word in the vocabulary of prisoners: "Shit!"

Now I have finally learned how things are. And what happens to me is what you might call the peak of the first phase of psychological reactions:I draw a line under all my former life.

On psychological reactions

Illusions collapsed, one by one. And then there was something unexpected: black humor. We realized that we had nothing to lose except a ridiculously naked body. Even in the shower, we began to exchange jokes (or pretending to do so) to cheer each other up and above all ourselves. Some reason for this was – after all, water really comes from the taps!

<...>

In addition to black humor, there was another sense of curiosity.

Personally, I was already familiar with this emergency response from a different field. In the mountains, in the collapse, desperately clinging and climbing, I felt for some seconds, even a split second, a kind of detached curiosity: will I live? Get a skull injury? Broken any bones?

And in Auschwitz people for a short time there was a state of objectification, detachment, a moment of almost cold curiosity, almost a sideways observation, when the soul, as it were, turns off and thereby tries to defend itself, to be saved. We were curious about what would happen next. How, for example, will we, completely naked and wet, come out of here in the cold of late autumn?

<...>

The hopelessness of the situation, the daily, hourly, minutely threat of death - all this led almost every one of us, even briefly, to the thought of suicide. But on the basis of my worldview, which will be discussed later, on the first evening, before I fell asleep, I gave myself the word “not to throw myself on the wire.” This specific camp expression denoted the local method of suicide - touching barbed wire, get a fatal shock of high voltage current.

<...>

Within a few days, psychological reactions begin to change. Having experienced the initial shock, the prisoner gradually plunges into the second phase - the phase of relative apathy, when something in his soul dies.

<...>

Apathy, inner stupor, indifference - these manifestations of the second phase of the psychological reactions of the prisoner made him less sensitive to daily, hourly beatings. It is this kind of insensitivity that can be considered the most necessary protective armor, with the help of which the soul tried to protect itself from heavy damage.

<...>

Come back.towardlethargyAs the main symptom of the second phase, it should be said thatThis is a special mechanism of psychological protection.. Reality is narrowing. All thoughts and feelings concentrate on one single task: to survive. And in the evening, when the exhausted people were returning from work, one sentence could be heard from everyone: well, another day is over!

<...>

It is quite understandable, therefore, that in the condition of such a psychological press, and under the pressure of the necessity of concentrating entirely on immediate survival, the whole psychic life was reduced to a rather primitive stage. Psychoanalytically oriented colleagues from among the comrades in misfortune often spoke of the “regression” of man in the camp, of his return to more primitive forms of mental life. This primitiveness of desires and aspirations was clearly reflected in the typical dreams of prisoners.

Humiliation.

The bodily pain inflicted by the beatings was not the most important for us prisoners (just as it was for the punished children).Mental pain, resentment against injustice - that, despite the apathy, tormented more.In this sense, even a blow that comes by can be painful.

Once, for example, we worked in a heavy snowstorm on the railway tracks. At least for the sake of not freezing completely, I very diligently trampled the rut with rubble, but at some point stopped to blow my nose. Unfortunately, it was at this point that the escort turned to me and, of course, decided that I was out of work.

The most painful thing for me in this episode was not the fear of disciplinary action, of beating. Despite the already utter, it would seem, mental stupor, I was extremely hurt that the escort did not consider that miserable creature, as I was in his eyes, worthy of even a swear word: as if playing, he lifted a stone from the ground and threw at me. I should have understood that this attracts the attention of an animal, so the livestock is reminded of its duties - indifferently, without condescending to punishment.

On the inner pillar

Psychological observations have shown that, among other things, the camp environment influenced character changes only in the prisoner who descended spiritually and in a purely human way. And he went down who no longer had any inner support. But now let us ask the question: what could and should have been such a support?

<...>

According to the unanimous opinion of psychologists and prisoners themselves, the man in the concentration camp was most depressing because he did not know at all how long he would be forced to stay there. There was no deadline!

<...>

The Latin word finis has two meanings: end and goal.A man who is unable to foresee the end of this temporary existence cannot thereby direct his life toward any goal.He can no longer, as it is generally characteristic of a person under normal conditions, orient himself to the future, which violates the general structure of his inner life as a whole, deprives him of support.

Similar conditions have been described in other areas, such as the unemployed. They too, in a sense, cannot firmly count on the future, set themselves a definite goal in this future. Among unemployed miners, psychological observations have revealed similar distortions in the perception of that particular time, which psychologists call “internal time” or “time experience.”

<...>

The inner life of the prisoner, who did not rely on the “goal in the future” and therefore descended, acquired the character of a retrospective existence. We have already spoken in another connection about the tendency to return to the past, that such immersion in the past devalues the present with all its horrors.But the devaluation of the present, surrounding reality is fraught with a certain danger - a person ceases to see at least some, even the slightest, possibilities of influencing this reality.But some heroic examples show that even in the camp such opportunities sometimes occurred.

The devaluation of reality, accompanying the “temporary existence” of prisoners, deprived a person of support, forcing him to finally fall down, lose heart – because “all is in vain anyway.”Such people forget that the most difficult situation gives a person the opportunity to rise internally above himself.Instead of viewing the external hardships of camp life as a test of their spiritual fortitude, they treated their present being as something from which to turn their backs, and, having closed themselves, completely immersed themselves in their past. And their lives were in decline.

Of course, few are capable of reaching inner heights amidst the horrors of a concentration camp. But there were. They were able to reach, in an external crash, and even in death, a peak which was unattainable to them in their daily existence.

<...>

It can be said that most of the people in the camp believed that all their possibilities of self-fulfillment were behind them, and yet they were only opening up.For it depended on the man himself whether he would turn his camp life into a vegetation like that of a thousand, or a moral victory like that of a few.

On hope and love

Kilometer by kilometer we walk next to him, drowning in the snow, then sliding on the icy boograms, supporting each other, hearing abuse and whining. We don’t say another word, but we know that each of us is thinking about his wife.

From time to time, I glance at the sky: the stars are already pale, and there, in the distance, the pink light of the morning dawn begins to break through the thick clouds. And before my spiritual gaze is a beloved man. My imagination managed to embody it so vividly, as vividly as it had never been in my previous, normal life. I talk to my wife, I ask questions, she answers. I see her smile, her cheering gaze, and—though this gaze is incorporeal—it shines brighter for me than the rising sun.

<...>

Suddenly a thought strikes me: for now, for the first time in my life, I have understood the truth of what so many thinkers and sages considered their final conclusion, that so many poets chanted: I understood, I accepted the truth.Only love is that finite and supreme which justifies our existence here, which can elevate and strengthen us!Yes, I understand the meaning of the result achieved by human thought, poetry, faith.Liberation - through love, in love!

I now know that a man who has nothing in the world can possess spiritually, even for a moment, the most precious image of the one he loves. In the most difficult of all imaginable difficult situations, when it is no longer possible to express oneself in any action, when the only suffering remains, in such a situation a person can realize himself by recreating and contemplating the image of the one he loves.

For the first time in my life, I was able to understand what is meant by saying that angels are happy with the loving contemplation of the infinite Lord.

<...>

Frozen earth does not lend itself well, solid lumps fly from under the pickaxe, sparks flash. We're not warm yet, we're still silent. And my spirit is again hovering around my beloved. I'm still talking to her, she's still answering me. Suddenly I thought, I don’t even know if she’s alive!

But I now know another thing: the less love is concentrated on the corporeal nature of man, the deeper it penetrates into his spiritual essence, the less essential his “so-being” (as philosophers call it), his “here-being”, “here-with-me-presence”, his corporeal existence in general becomes.

In order to evoke the spiritual image of my beloved now, I do not need to know whether she is alive or not. Had I known at that moment that she was dead, I am sure that in spite of this knowledge, she would still have evoked her spiritual image, and my spiritual dialogue with him would have been just as intense and filled all of me. For I felt at that moment the truth of the words of the Song of Songs:Set me as a seal on your heart, for love is as strong as death.(8:6).

<...>

Listen, Otto! If I don't go home to my wife, and if you see her, you'll tell her, listen carefully! First, we talked about it every day, remember? Second, I didn't love anyone more than her. Thirdly, the short time that we were with her has remained for me such a happiness that outweighs all the bad, even what is to be experienced now.

About inner life

Sensitive people, accustomed from a young age to the predominance of spiritual interests, endured the camp situation, of course, extremely painful, but in the spiritual sense it acted on them less destructively, even with their mild nature. Because they were more accessible.Return from this terrible reality to a world of spiritual freedom and inner riches. It is this and only this that can explain the fact that people of fragile build sometimes better resisted the camp reality than outwardly strong and strong.

<...>

Retirement meant for those who were capable of this, an escape from the joyless desert, from the spiritual poverty of the local existence back to their own past. Fantasy was constantly busy restoring past impressions. And most often these were not some significant events and deep experiences, but details of everyday life, signs of a simple, calm life. In sad memories, they come to the prisoners, bringing them light.

Turning away from the present surrounding him, returning to the past, a person mentally restored some of his reflections, prints. The whole world, the whole past life, was taken away from him, moved far away, and the longing soul rushes after the departed - there, there. Here you go in the tram; here you come home, open the door; here the phone rings, you pick up the phone; you light up the light. Such simple, at first glance ridiculously insignificant details touch, touch to tears.

<...>

Those who retained the capacity for inner life did not lose the ability to perceive the beauty of nature or art at least occasionally, even when the slightest opportunity was given.And the intensity of this experience, even for some moments, helped to disconnect from the horrors of reality, to forget about them.

When we moved from Auschwitz to the Bavarian camp, we looked through barred windows at the peaks of the Salzburg Mountains, illuminated by the setting sun. If anyone had seen our admiring faces at this moment, they would never have believed that they were people whose lives were almost over. And in spite of that -- or precisely because of that? -- we were captivated by the beauty of nature, the beauty from which we had been detached for years.

Happiness

Happiness is when the worst gets by.

<...>

We were grateful for the slightest relief. Some new trouble might have happened, but it didn’t.. We rejoiced, for example, if in the evening, before going to bed, nothing prevented us from destroying lice. Of course, this in itself is not such a pleasure, especially since it was necessary to undress naked in an unheated barracks, where icicles dangled from the ceiling (inside the room!). But we thought we were lucky if there was no air alert and no blackout at that point, which meant that this interrupted activity took us midnight.

<...>

But back to relativity. A long time later, after his release, someone showed me a picture in an illustrated newspaper: a group of concentration camp inmates lying on their high-rise bunks and staring bluntly at the person who was photographing them. "Isn't it terrible - these faces, all this?" they asked me. I wasn't terrified. Because at that moment, I had this picture before me.

Five in the morning. It's still a dark night. I lie on bare boards in the dugout, where almost 70 more comrades are on lightweight mode. We are marked as sick and can not go to work, do not stand in formation on the parade ground. We lie close together, not only because of the cramping, but also to keep the crumbs warm. We are so tired that we do not need to move our arm or leg.

All day, lying down like this, we'll wait for our cut-down portions of bread and watery soup. How happy we are, how happy we are!

Outside, from the end of the parade ground, where the night shift should return, you can hear whistles and sharp screams. The door opens, a snow whirlwind bursts into the dugout and a figure covered with snow appears in it. Our exhausted, barely standing comrade is trying to sit on the edge of the Nar. But the senior in the block pushes him back, because in this dugout is strictly forbidden to enter those who are not on the "light mode".

How sorry I am for this comrade! And how happy I am not to be in his shoes, and to remain in the "light" barracks. And what a salvation - to get in the outpatient camp infirmary "relief" for two, and then, in addition, for two more days! To the typhoid camp?

On personal depreciation

We have already talked about the depreciation to which, with few exceptions, everything that did not directly serve to preserve life has been subjected. And this revision led to the fact that in the end man ceased to value himself, that in the vortex that plunged into the abyss of all former values, the personality was drawn.

Under a certain suggestive influence of that reality, which has long wanted to know nothing about the value of human life, about the significance of the personality, which turns a person into an unrequited object of destruction (previously using, however, the remnants of his physical abilities), under this influence, his own self is ultimately devalued.

<...>

A person who is not able to oppose himself to reality with the last rise of self-esteem generally loses the feeling of himself as a subject in the concentration camp, not to mention the feeling of himself as a spiritual being with a sense of inner freedom and personal value.

He begins to perceive himself rather as a particle of some great mass, his being descends to the level of herd existence. After all, people, regardless of their own thoughts and desires, are driven here and there, alone or all together, like a flock of sheep. Right and left, front and back, you are chased by a small but powerful, armed gang of sadists who, with kicks, kicks, boots, rifle butts, force you to move back and forth.

We have reached the state of a flock of sheep that only know to avoid dog attacks and, when left alone for a moment, eat a little. And like sheep, fearfully straying into a heap at the sight of danger, each of us sought not to remain at the edge, to get into the middle of his row, in the middle of his column, in the head and tail of which there were convoys.

In addition, the place in the center of the column promised some protection from the wind. So that the state of man in the camp, which can be called the desire to dissolve in the general mass, arose not only under the influence of the environment, it was also an impulse of self-preservation. The desire of each to dissolve in the mass was dictated by one of the most important laws of self-preservation in the camp: the main thing is not to stand out, not to attract the attention of the SS for any reason!

<...>

A person lost the feeling of himself as a subject not only because he was completely subject to the arbitrariness of the camp guards, but also because he felt dependence on pure accidents, became a toy of fate. I have always thought and maintained that a person begins to understand why this or that has happened in his life and what has been good for him, only after a while, five or ten years. In the camp, this sometimes became clear after five or ten minutes.

Internal freedom

There are many examples, often truly heroic, that show that you can overcome apathy, curb irritation. That even in this situation, which is absolutely overwhelming both externally and internally, it is possible to preserve the remnants of spiritual freedom, to oppose this pressure with your spiritual self.

Who among the survivors of the concentration camp could not tell about the people who, walking with everyone in the column, passing through the barracks, gave someone a kind word, and with someone shared the last crumbs of bread?

And even if there were few of them, their example confirms that in a concentration camp you can take away everything from a person except the last one - human freedom, freedom to relate to circumstances, or one way or another. And it was “one way or another” they had.

And every day, every hour in the camp gave a thousand opportunities to make this choice, to renounce or not to renounce the most secret that the surrounding reality threatened to take away - from inner freedom. And to renounce freedom and dignity meant to become an object of the influence of external conditions, to allow them to fashion out of you a “typical” camper.

<...>

No, experience confirms that the mental reactions of the prisoner were not just a natural imprint of bodily, mental and social conditions, calorie deficit, lack of sleep and various psychological “complexes”. Ultimately, it turns out:What happens inside a person, what the camp allegedly “makes out of him” is the result of the inner decision of the person himself.. In principle, it depends on each person what, even under the pressure of such terrible circumstances, will happen in the camp with him, with his spiritual, inner essence: whether he will turn into a “typical” camp or remain a person here, preserve his human dignity. published

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Join us on Facebook, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: monocler.ru/psiholog-v-kontslagere-viktor-frankl-o-vnutrenney-svobode-i-smyisle-zhizni/