516

As we learn justice

Two brown Capuchin monkey sitting in a cage. From time to time they are given coins that they can exchange for food. Everyone knows that the Capuchins prefer grapes to cucumbers. So what happens when a manifest injustice – when in exchange for the same coin one monkey receives a cucumber and the other grapes?

When Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Val did this experiment in 2003, focusing mainly on the females of Capuchin, they found that monkeys hate it when infringe their rights. Alone, the monkey happily eats the grape and a piece of cucumber.

But if she sees that her partner received a grape, while they gave her a cucumber, she'd be pissed – maybe even throw the cucumber out of the cage. Some of the primates "don't like inequality", as explained by Brosnan and de Val. They hate to less. Psychologists have this term aversion to disadvantageous inequality. It's an instinctual aversion to getting less than others, there are chimpanzees, dogs, and, of course, people.

Moreover, people have this feeling develops from an early age. Psychologists Geraci Alessandra and Luca Surian found, for example, that children under the age of one year prefer fair cartoon characters unfair.

And yet for people's aversion to receiving a smaller – is only one aspect of injustice. Unlike animals, sometimes we try to prevent people to get more. That is, we experience aversion to advantageous inequality. In some situations, we even give up something good, because it is more than others have. At such moments, we want the goods distributed fairly and equally. We don't want to take less but get more.

It seems that our aversion to disadvantageous position innate, because we share her with other animals. Psychologists ask another question – is our antipathy to gain from inequality is innate or we got it from some form of socialization.

In December, psychologists Peter Blake, Katherine Magalif, Felix Warneken and their colleagues published the results of experiments aimed at addressing this issue. Their study covered several countries – India, Uganda, Peru, Senegal, Mexico, Canada and the United States. They examined 900 children aged 4 to 15 years in order to understand whether there is aversion to advantageous inequality in all of these cultures, and if so, is it the same everywhere or not.

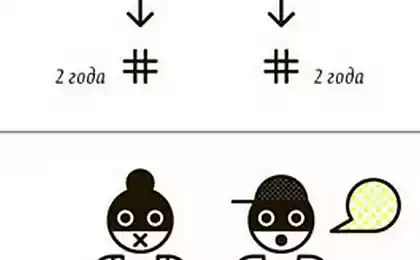

The method was quite simple. They put two children at the table and before each of them put the empty bowl. Above each bowl there was a tray, on which scientists put a piece of candy. Very often scientists distributed sweets unfairly: put 4 candies in one tray and one on the second. Then the child was given a choice. If the child was pulling the green lever, and this meant that he takes the candy, and they fell into his bowl; if the child chose the red lever so he refused the chocolates, and they fell in a third bowl, standing in the center.

Scientists have found that children of different nationalities often refused candy when the division was in favor of the second child. (That is, they refused to disadvantageous inequality). Also some kids (older) refused to advantageous inequality. Nothing surprising.

Advantageous inequality is common among adults; in one study, economist George Lowenstein and his colleagues 66% of the subjects did not want to more than others. The amazing thing is that the children showed favorable inequality in only three countries: Canada, United States and Uganda. In other countries – Mexico, India, Senegal and Peru – they were enjoying the sweet taste of inequality.

These results give rise to some questions. Why children from certain countries are worried about an unfair advantage? And why they refused unfair offers because they are important justice or for some other reason?

Perhaps we should move away from the more complex case of great inequality to a simpler case of disadvantageous inequality. There are many reasons to oppose disadvantageous inequality, and some of them are quite obvious. Disadvantageous inequality is bad, because you get less candy.

But it's bad also in social terms, because it speaks of the shift in social status. When children refuse unfavorable suggestions, they do it rather because I'm worried about your social situation, or abstract ideas like inequality, not about the candy. It is not about what is good and what is bad. It's me: how do I get out of this situation?

The importance of social hierarchy in the rejection of disadvantageous unfairness clearly demonstrated in some experiments. One of them psychologists mark I have great access, Paul bloom and Karen Wynn, of children forced to choose: get one coin and give it to another child or to obtain two coins and three to give to another child. "You would think that the second option is better because both children get more," writes bloom in her book "Just kids". But often children choose the first option – the one coin for everyone not to get less than someone else.

In another version of this study, bloom and his colleagues offered the children a choice: two coins or one coin to one and no to the second. Children aged 5 and 6 years chose the second option: that is, they refused the award in exchange to get more than their peers. "We have a natural aversion to receiving a smaller – but not to inequality," says bloom. Children's behavior is unprincipled, contrary – bloom believes that his motivating kind of anger. And the message is pretty clear: I want to be at the top. A finite number of candies is not as important as my social status.

If disadvantageous inequality is related to the status, not for justice, can the same be said about advantageous inequality? In the end, refusing lucrative offers, we, too, serves a social signal. If you live in a society where the idea of justice and equality are paramount, then you it is important to show these ideals in action, even at a loss.

Others may think that since you believe in equality, no matter what, so you're valuable, worthy of respect. From this point of view, and disadvantageous and advantageous inequality have the same result: they aimed at maintaining their status. Perhaps for adult children who are already moving in the period of youth, the status doesn't always mean getting more. Perhaps their status is a desire to become a role model.

If disadvantageous and advantageous inequality is indeed driven by social status, this could explain one of the countries that participated in that study: Mexico. In the country very few children showed favorable inequity; furthermore, disadvantageous inequality develops in such societies in the later stages of growing up.

In other words, Mexican children were inclined to accept all offers, no matter how unequal they may be. The authors highlight that in this particular case, most of the kids already knew each other. Perhaps they have had a reputation in which the results of the study cannot be transferred to the real social hierarchy. They can enjoy the sweets without social signals.

And yet, even if advantageous and disadvantageous inequality has a lot in common (status), a study of Blake and his colleagues suggests that they differ from each other at least in one. The sense of disadvantageous inequality is inherent: all over the world, even in the animal Kingdom, a smaller proportion considered an insult. On the other hand, advantageous inequality seems to be a product of social life or culture.

Worldwide, at least among children, this kind of inequality is distributed unevenly. In Canada, the USA and Uganda, the study showed that older children will likely abandon best deals. In Mexico, Peru, India and Senegal, on the contrary, they are happy to accept a greater share. In the past, research the best inequality was devoted to the so-called WEIRD societies – Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic. The result is an uneven distribution of advantageous inequity is gone from the radar.

To explain the uneven distribution, Blake and his colleagues have identified a number of potential cases. Most striking are the "Western norm". They assume that aversion to advantageous inequality is present more in the Western countries, because the West equality and the abstract concept of "justice" is regarded as a good thing; it is in this context a donation of their own interests in the name of justice associated with the status.

In a recent study Makolet, Blake, Warneken and their colleagues found that disadvantageous inequality is manifested only in the absence of a visible partner, and the advantageous inequality appeared in social situations. Perhaps this suggests that the appearance of great inequality need certain types of social environment.

If in the advantageous inequality is the fault of Western culture, then why is it so common in Uganda? Blake and his colleagues believe that the answer lies in the variety of the Ugandan population that they investigated. They recruited children from schools, which taught Western teachers. Perhaps this environment has changed the sense of justice of these guys.

This argument seems rather weak: do other companies not exposed to Western norms, especially now, in the age of smartphones and Internet? "Perhaps the children in Uganda refuse benefits for other reasons not related to the Western standards, the authors write. – If so, you can expect to see the manifestation of great inequality among children in other communities in Uganda with similar cultural norms, but other organizational structures."

But the question of how "Western" can be considered advantageous inequality, lies another, broader question. What are the factors that companies could create a rule in which it is important to show yourself to others as someone who wants to get more than others? George Loewenstein, tried to understand what conditions could lead to the emergence of aversion to advantageous inequality in the first place. He began with that asked subjects to imagine themselves in a certain situation.

In the first case, the subjects invented a new kind of skiing together with other scientists; otherwise, they shared the income from the land with its neighbour; and in the third, they were arguing with the seller at the store. In each of these scenarios, their prior relationships with their "partners" were described as positive, negative or neutral, and the financial payments were either the same, or was a disadvantageous or advantageous inequality.

As expected, when it came to disadvantageous inequality, nobody wanted to get less than their partner. But the best inequality manifested themselves unevenly; in some situations it did not exist. In situations with the invention and with taxes it came immediately – if the relationship was positive or neutral; in a situation with the seller, it appeared relatively infrequently; and if the relationship was negative, it did not appear. (In this case people preferred to more).

Based on a selection of subjects, Loewenstein divided them into three groups: saints, loyalists, and ruthless competitors. The saints prefer equality in the first place; they were interested in justice. Loyalists preferred the equality in positive ways but in negative preferred advantageous inequality – they would approach relationships from a social point of view, trying to create the devotion, abandoning their unfair advantages.

Ruthless opponents always preferred to more. The relative percentage of saints, loyalists and opponents was 24, 27 and 36, respectively. (18% of subjects not subject to classification). Then Loewenstein explained prior relationships, giving the subjects a few paragraphs of explanation as to why this relationship was positive, negative or neutral. Under this condition, the number of saints and ruthless opponents fell, and the percentage of loyalists rose to as much as 52%.

When the subjects got more context to explore social scenarios and learned more about these relationships, they were willing to pay more just to support them. And rightly so. The results of another experiment show that the more someone earns, in the context of inequality, the more hostile the reaction from other people. People don't like those upstairs.

All these studies can tell us why we value fairness. Our ideas about justice are relative, not absolute. In many ways, we believe justice is a form of social signal. Most people don't care about equality as an abstract principle; instead, they rely on justice to take its place in the social hierarchy. And so we are especially ready to abandon unfair advantage when there is an opportunity to strengthen future relations.

Happy family of 13 people

What happens to people in between 20 to 30 years

Can these General principles to explain why inequality is sooner or more in some societies? Perhaps, but to receive a clear answer to this question will have to spend more than one study.

We know one thing: culture plays an important role. But what is culture? If she could teach? Maybe if we find the answer to this question, we can build a world in which there will be more saints and fewer loyalists and ruthless rivals. published

Author: Maria Konnikova

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: newyorker-ru.livejournal.com/62428.html

When Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Val did this experiment in 2003, focusing mainly on the females of Capuchin, they found that monkeys hate it when infringe their rights. Alone, the monkey happily eats the grape and a piece of cucumber.

But if she sees that her partner received a grape, while they gave her a cucumber, she'd be pissed – maybe even throw the cucumber out of the cage. Some of the primates "don't like inequality", as explained by Brosnan and de Val. They hate to less. Psychologists have this term aversion to disadvantageous inequality. It's an instinctual aversion to getting less than others, there are chimpanzees, dogs, and, of course, people.

Moreover, people have this feeling develops from an early age. Psychologists Geraci Alessandra and Luca Surian found, for example, that children under the age of one year prefer fair cartoon characters unfair.

And yet for people's aversion to receiving a smaller – is only one aspect of injustice. Unlike animals, sometimes we try to prevent people to get more. That is, we experience aversion to advantageous inequality. In some situations, we even give up something good, because it is more than others have. At such moments, we want the goods distributed fairly and equally. We don't want to take less but get more.

It seems that our aversion to disadvantageous position innate, because we share her with other animals. Psychologists ask another question – is our antipathy to gain from inequality is innate or we got it from some form of socialization.

In December, psychologists Peter Blake, Katherine Magalif, Felix Warneken and their colleagues published the results of experiments aimed at addressing this issue. Their study covered several countries – India, Uganda, Peru, Senegal, Mexico, Canada and the United States. They examined 900 children aged 4 to 15 years in order to understand whether there is aversion to advantageous inequality in all of these cultures, and if so, is it the same everywhere or not.

The method was quite simple. They put two children at the table and before each of them put the empty bowl. Above each bowl there was a tray, on which scientists put a piece of candy. Very often scientists distributed sweets unfairly: put 4 candies in one tray and one on the second. Then the child was given a choice. If the child was pulling the green lever, and this meant that he takes the candy, and they fell into his bowl; if the child chose the red lever so he refused the chocolates, and they fell in a third bowl, standing in the center.

Scientists have found that children of different nationalities often refused candy when the division was in favor of the second child. (That is, they refused to disadvantageous inequality). Also some kids (older) refused to advantageous inequality. Nothing surprising.

Advantageous inequality is common among adults; in one study, economist George Lowenstein and his colleagues 66% of the subjects did not want to more than others. The amazing thing is that the children showed favorable inequality in only three countries: Canada, United States and Uganda. In other countries – Mexico, India, Senegal and Peru – they were enjoying the sweet taste of inequality.

These results give rise to some questions. Why children from certain countries are worried about an unfair advantage? And why they refused unfair offers because they are important justice or for some other reason?

Perhaps we should move away from the more complex case of great inequality to a simpler case of disadvantageous inequality. There are many reasons to oppose disadvantageous inequality, and some of them are quite obvious. Disadvantageous inequality is bad, because you get less candy.

But it's bad also in social terms, because it speaks of the shift in social status. When children refuse unfavorable suggestions, they do it rather because I'm worried about your social situation, or abstract ideas like inequality, not about the candy. It is not about what is good and what is bad. It's me: how do I get out of this situation?

The importance of social hierarchy in the rejection of disadvantageous unfairness clearly demonstrated in some experiments. One of them psychologists mark I have great access, Paul bloom and Karen Wynn, of children forced to choose: get one coin and give it to another child or to obtain two coins and three to give to another child. "You would think that the second option is better because both children get more," writes bloom in her book "Just kids". But often children choose the first option – the one coin for everyone not to get less than someone else.

In another version of this study, bloom and his colleagues offered the children a choice: two coins or one coin to one and no to the second. Children aged 5 and 6 years chose the second option: that is, they refused the award in exchange to get more than their peers. "We have a natural aversion to receiving a smaller – but not to inequality," says bloom. Children's behavior is unprincipled, contrary – bloom believes that his motivating kind of anger. And the message is pretty clear: I want to be at the top. A finite number of candies is not as important as my social status.

If disadvantageous inequality is related to the status, not for justice, can the same be said about advantageous inequality? In the end, refusing lucrative offers, we, too, serves a social signal. If you live in a society where the idea of justice and equality are paramount, then you it is important to show these ideals in action, even at a loss.

Others may think that since you believe in equality, no matter what, so you're valuable, worthy of respect. From this point of view, and disadvantageous and advantageous inequality have the same result: they aimed at maintaining their status. Perhaps for adult children who are already moving in the period of youth, the status doesn't always mean getting more. Perhaps their status is a desire to become a role model.

If disadvantageous and advantageous inequality is indeed driven by social status, this could explain one of the countries that participated in that study: Mexico. In the country very few children showed favorable inequity; furthermore, disadvantageous inequality develops in such societies in the later stages of growing up.

In other words, Mexican children were inclined to accept all offers, no matter how unequal they may be. The authors highlight that in this particular case, most of the kids already knew each other. Perhaps they have had a reputation in which the results of the study cannot be transferred to the real social hierarchy. They can enjoy the sweets without social signals.

And yet, even if advantageous and disadvantageous inequality has a lot in common (status), a study of Blake and his colleagues suggests that they differ from each other at least in one. The sense of disadvantageous inequality is inherent: all over the world, even in the animal Kingdom, a smaller proportion considered an insult. On the other hand, advantageous inequality seems to be a product of social life or culture.

Worldwide, at least among children, this kind of inequality is distributed unevenly. In Canada, the USA and Uganda, the study showed that older children will likely abandon best deals. In Mexico, Peru, India and Senegal, on the contrary, they are happy to accept a greater share. In the past, research the best inequality was devoted to the so-called WEIRD societies – Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic. The result is an uneven distribution of advantageous inequity is gone from the radar.

To explain the uneven distribution, Blake and his colleagues have identified a number of potential cases. Most striking are the "Western norm". They assume that aversion to advantageous inequality is present more in the Western countries, because the West equality and the abstract concept of "justice" is regarded as a good thing; it is in this context a donation of their own interests in the name of justice associated with the status.

In a recent study Makolet, Blake, Warneken and their colleagues found that disadvantageous inequality is manifested only in the absence of a visible partner, and the advantageous inequality appeared in social situations. Perhaps this suggests that the appearance of great inequality need certain types of social environment.

If in the advantageous inequality is the fault of Western culture, then why is it so common in Uganda? Blake and his colleagues believe that the answer lies in the variety of the Ugandan population that they investigated. They recruited children from schools, which taught Western teachers. Perhaps this environment has changed the sense of justice of these guys.

This argument seems rather weak: do other companies not exposed to Western norms, especially now, in the age of smartphones and Internet? "Perhaps the children in Uganda refuse benefits for other reasons not related to the Western standards, the authors write. – If so, you can expect to see the manifestation of great inequality among children in other communities in Uganda with similar cultural norms, but other organizational structures."

But the question of how "Western" can be considered advantageous inequality, lies another, broader question. What are the factors that companies could create a rule in which it is important to show yourself to others as someone who wants to get more than others? George Loewenstein, tried to understand what conditions could lead to the emergence of aversion to advantageous inequality in the first place. He began with that asked subjects to imagine themselves in a certain situation.

In the first case, the subjects invented a new kind of skiing together with other scientists; otherwise, they shared the income from the land with its neighbour; and in the third, they were arguing with the seller at the store. In each of these scenarios, their prior relationships with their "partners" were described as positive, negative or neutral, and the financial payments were either the same, or was a disadvantageous or advantageous inequality.

As expected, when it came to disadvantageous inequality, nobody wanted to get less than their partner. But the best inequality manifested themselves unevenly; in some situations it did not exist. In situations with the invention and with taxes it came immediately – if the relationship was positive or neutral; in a situation with the seller, it appeared relatively infrequently; and if the relationship was negative, it did not appear. (In this case people preferred to more).

Based on a selection of subjects, Loewenstein divided them into three groups: saints, loyalists, and ruthless competitors. The saints prefer equality in the first place; they were interested in justice. Loyalists preferred the equality in positive ways but in negative preferred advantageous inequality – they would approach relationships from a social point of view, trying to create the devotion, abandoning their unfair advantages.

Ruthless opponents always preferred to more. The relative percentage of saints, loyalists and opponents was 24, 27 and 36, respectively. (18% of subjects not subject to classification). Then Loewenstein explained prior relationships, giving the subjects a few paragraphs of explanation as to why this relationship was positive, negative or neutral. Under this condition, the number of saints and ruthless opponents fell, and the percentage of loyalists rose to as much as 52%.

When the subjects got more context to explore social scenarios and learned more about these relationships, they were willing to pay more just to support them. And rightly so. The results of another experiment show that the more someone earns, in the context of inequality, the more hostile the reaction from other people. People don't like those upstairs.

All these studies can tell us why we value fairness. Our ideas about justice are relative, not absolute. In many ways, we believe justice is a form of social signal. Most people don't care about equality as an abstract principle; instead, they rely on justice to take its place in the social hierarchy. And so we are especially ready to abandon unfair advantage when there is an opportunity to strengthen future relations.

Happy family of 13 people

What happens to people in between 20 to 30 years

Can these General principles to explain why inequality is sooner or more in some societies? Perhaps, but to receive a clear answer to this question will have to spend more than one study.

We know one thing: culture plays an important role. But what is culture? If she could teach? Maybe if we find the answer to this question, we can build a world in which there will be more saints and fewer loyalists and ruthless rivals. published

Author: Maria Konnikova

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: newyorker-ru.livejournal.com/62428.html

Goodbye, gasoline: Toyota began serial production of cars that drive on hydrogen

Started sales of the updated sedan Honda Accord Hybrid