271

Everything you need to know about auditory hallucinations

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the quality of real perception.

Hallucinations can occur for all senses:

Probably, most common hallucinations manifests itself in the fact that man "hearing voices". These are called auditory verbal hallucinations. They are often symptoms of psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia. Visual hallucinations They can also be associated with pathologies. Although they are less common in schizophrenia, sometimes visual hallucinations occur in neurological disorders and dementia.

Definition of the concept

Although auditory hallucinations are commonly associated with psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar disorder, they are not always signs of the disease. In some cases, hallucinations may be caused bylack of sleep. marijuana stimulant It can also cause perception disorders in some people. It has been shown that hallucinations can cause and prolonged absence of sensory stimuli.

In the 1960s, experiments were conducted (which would not be possible for ethical reasons now) in which people were kept in dark rooms without sound or any sensory stimuli. Eventually, people began to see and hear things that were not there. So hallucinations can occur in both patients and mentally healthy people.

Studies of hallucinations have been going on for a long time. Psychiatrists and psychologists have been trying to understand the causes and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations for about a century (perhaps longer). In the last three decades, we've had the opportunity to use encephalograms to try to understand what happens in the brain when people experience auditory hallucinations. We can now look at areas of the brain involved in hallucinations using functional magnetic resonance scans or positron tomography. This has helped psychologists and psychiatrists develop models of auditory hallucinations in the brain, mainly related to language and speech function.

Proposed theories of mechanisms of auditory hallucinations

When patients experience auditory hallucinations, i.e. hearing voices, a part of their brain called the Broca area, according to some reports, becomes more active. This area is located in the small frontal lobe of the brain and is responsible for speech production - when you speak, Broca's area works!

Some of the first to investigate this phenomenon were Professors Philip McGuire and Suhi Shergill of King's College London. They showed that Broca's area in their patients was more active during auditory hallucinations than when voices were silent. This suggests that auditory hallucinations are produced by the speech and language centers of our brains. This led to the creation of “internal” models of auditory hallucinations.

When we think about something, we generate an “inner speech”, that is, an inner voice that “voices” our thinking. For example, when we think, “What am I going to eat for lunch?” or “What is the weather going to be tomorrow?” we generate inner speech and we think activate Broca’s zone.

But how does this inner speech begin to be perceived as external, not coming from itself? Internal models of auditory verbal hallucinations suggest that Voices are thoughts generated within consciousness, or inner speech, somehow misdefined as external, alien voices.. This leads to more complex models of how we track our own inner speech.

Chris Frith and others have suggested that when we enter the process of thinking and inner speech, our Broca area sends a signal to a region of our auditory cortex called the Wernick area. This signal contains information that the speech we perceive is generated by us. This is because the signal is supposed to mute the neural activity of the sensory cortex, so it is activated less than from external stimuli, such as someone talking to you.

This model is known as the self-monitoring model, and it suggests that people with auditory hallucinations lack this monitoring process, which makes them unable to distinguish between internal and external speech.

While the evidence for this theory is somewhat weak at this point, it has definitely been one of the most influential models of auditory hallucinations in the last twenty or thirty years.

Effects of hallucinations

About 70% of people with schizophrenia hear voices to some degree. Sometimes voices "react" to medications, sometimes they don't. Usually, though not always, voices have a negative impact on people’s lives and health.

For example, people who hear voices and do not respond to treatment have a higher risk of suicide. Sometimes voices tell them to hurt themselves. You can imagine how hard it is for them even in everyday situations, when they constantly hear humiliating and offensive words in their address.

However, it would be a big simplification to say that only people with mental disorders experience auditory hallucinations. Moreover, these voices are not always angry. There is a very active Society of Hearing Voices, led by Marius Romm and Sandra Escher. This movement speaks to the positive aspects of voices and fights against their stigmatization.

Many people who hear voices live active and happy lives, so we can’t assume that voices are always bad. They are often associated with aggressive, paranoid, and anxious behaviors of the mentally ill, but these behaviors may be the result of their emotional distress, not the voices themselves. Perhaps not surprisingly, the anxiety and paranoia that are often at the core of mental illness are manifested in what voices say.

It is worth noting that eat Many people without a psychiatric diagnosis report hearing voices. For these people, voices can be a positive experience as they calm or even guide them in life. Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has thoroughly investigated this phenomenon. She found a group of healthy and well-functioning people hearing voices. They described their “voices” as something positive, helpful, and self-assurance.

Treatment of hallucinations

People diagnosed with schizophrenia are usually treated with "antipsychotic" medications. These medications block postsynaptic dopamine receptors in an area of the brain called the striatum. Antipsychotics are effective for many patients, and as a result of treatment, their psychotic symptoms are reduced to some extent, especially auditory hallucinations and manias.

However, the symptoms of many patients do not seem to respond well to antipsychotics. Approximately 25-30% of patients who hear voices, drugs are almost not affected. Antipsychotics also have serious side effects, so these medications are not suitable for all patients.

As for other treatments, There are many options for non-drug intervention. The degree of their effectiveness also varies. Example: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The use of CBT to treat psychosis is somewhat controversial, as quite a few researchers believe it has little effect on symptoms and overall outcome. There are some types of CBT designed specifically for patients who hear voices. These therapies usually aim to change the patient's attitude to the voice so that it is perceived as less negative and unpleasant. The effectiveness of this treatment is in question.

I'm currently leading a study at King's College London in which we're trying to see if we can teach patients to self-regulate neural activity in the auditory cortex.

This is achieved by “reverse neural communication in real-time MRI.” An MRI scanner is used to measure the signal coming from the auditory cortex. This signal is then sent back to the patient via a visual interface that the patient must learn to control (i.e., move the lever up and down). Eventually, we expect to be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control their auditory cortex activity, which could allow them to control their voices more effectively. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months.

Population prevalence

Around 24 million people around the world are living with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and about 60% or 70% of them have heard voices at some point. Across the population, between 5% and 10% of people without a psychiatric diagnosis have also heard voices at some point in their lives. Most of us have ever thought that someone calls us by name, and then it turns out that there is no one around. So there is evidence that hallucinations may not be accompanied by schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. Auditory hallucinations are more common than we think, although exact epidemiological statistics are difficult to pin down.

The most famous person to hear voices was probably Joan of Arc. From modern history, one can recall Sid Barrett, the founder of Pink Floyd, who suffered from schizophrenia and heard voices. However, again, many people without a psychiatric diagnosis hear voices but perceive them very positively. They can draw inspiration from their voices for art. Some, for example, experience musical hallucinations. It can be a kind of vivid auditory images, or just a kind of them – these people hear music very clearly in their heads. Scientists are not very sure if this equates to hallucinations.

Unanswered questions

Science does not have a clear answer to the question of what happens in the brain when a person hears voices. Another problem is that researchers don’t yet know why people perceive them as aliens coming from an external source. It is important to try to understand the phenomenological aspect of what people who hear voices experience.

For example, when people get tired or take stimulants, they may experience hallucinations, but do not necessarily perceive them as coming from outside sources.

The question is why people lose their sense of action when they hear voices. Even if we think that the reason for auditory hallucinations is the excessive activity of the auditory cortex, why do people still believe that the voice of God or a secret agent or aliens is speaking to them? It is also important to understand the belief systems that people build around their voices.

The content of auditory hallucinations and its source is another problem: Do these voices come from inner speech, or are they stored memories? It is safe to say that this sensory experience involves activation of the auditory cortex in the speech and language areas. It tells us nothing about the emotional content of these voices, which can often be negative. From this, in turn, it follows that there may be a problem in the brain when processing emotional information.

Also interesting: Seven mental hallucinations. Blocks of conscious management

Scientists about the brain: the best TED lectures with Russian voiceover

In addition, two people can experience hallucinations very differently, which means that the brain mechanisms involved can be quite different. published

Credit Paul Allen

Translated by Kirill Kozlovsky

Source: vk.com/public80512191?w=page-80512191_51115432

Hallucinations can occur for all senses:

- auditory

- visual

- tactile

- olfactory.

Probably, most common hallucinations manifests itself in the fact that man "hearing voices". These are called auditory verbal hallucinations. They are often symptoms of psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia. Visual hallucinations They can also be associated with pathologies. Although they are less common in schizophrenia, sometimes visual hallucinations occur in neurological disorders and dementia.

Definition of the concept

Although auditory hallucinations are commonly associated with psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar disorder, they are not always signs of the disease. In some cases, hallucinations may be caused bylack of sleep. marijuana stimulant It can also cause perception disorders in some people. It has been shown that hallucinations can cause and prolonged absence of sensory stimuli.

In the 1960s, experiments were conducted (which would not be possible for ethical reasons now) in which people were kept in dark rooms without sound or any sensory stimuli. Eventually, people began to see and hear things that were not there. So hallucinations can occur in both patients and mentally healthy people.

Studies of hallucinations have been going on for a long time. Psychiatrists and psychologists have been trying to understand the causes and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations for about a century (perhaps longer). In the last three decades, we've had the opportunity to use encephalograms to try to understand what happens in the brain when people experience auditory hallucinations. We can now look at areas of the brain involved in hallucinations using functional magnetic resonance scans or positron tomography. This has helped psychologists and psychiatrists develop models of auditory hallucinations in the brain, mainly related to language and speech function.

Proposed theories of mechanisms of auditory hallucinations

When patients experience auditory hallucinations, i.e. hearing voices, a part of their brain called the Broca area, according to some reports, becomes more active. This area is located in the small frontal lobe of the brain and is responsible for speech production - when you speak, Broca's area works!

Some of the first to investigate this phenomenon were Professors Philip McGuire and Suhi Shergill of King's College London. They showed that Broca's area in their patients was more active during auditory hallucinations than when voices were silent. This suggests that auditory hallucinations are produced by the speech and language centers of our brains. This led to the creation of “internal” models of auditory hallucinations.

When we think about something, we generate an “inner speech”, that is, an inner voice that “voices” our thinking. For example, when we think, “What am I going to eat for lunch?” or “What is the weather going to be tomorrow?” we generate inner speech and we think activate Broca’s zone.

But how does this inner speech begin to be perceived as external, not coming from itself? Internal models of auditory verbal hallucinations suggest that Voices are thoughts generated within consciousness, or inner speech, somehow misdefined as external, alien voices.. This leads to more complex models of how we track our own inner speech.

Chris Frith and others have suggested that when we enter the process of thinking and inner speech, our Broca area sends a signal to a region of our auditory cortex called the Wernick area. This signal contains information that the speech we perceive is generated by us. This is because the signal is supposed to mute the neural activity of the sensory cortex, so it is activated less than from external stimuli, such as someone talking to you.

This model is known as the self-monitoring model, and it suggests that people with auditory hallucinations lack this monitoring process, which makes them unable to distinguish between internal and external speech.

While the evidence for this theory is somewhat weak at this point, it has definitely been one of the most influential models of auditory hallucinations in the last twenty or thirty years.

Effects of hallucinations

About 70% of people with schizophrenia hear voices to some degree. Sometimes voices "react" to medications, sometimes they don't. Usually, though not always, voices have a negative impact on people’s lives and health.

For example, people who hear voices and do not respond to treatment have a higher risk of suicide. Sometimes voices tell them to hurt themselves. You can imagine how hard it is for them even in everyday situations, when they constantly hear humiliating and offensive words in their address.

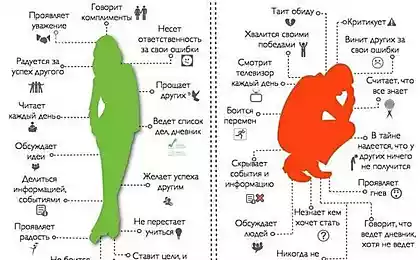

However, it would be a big simplification to say that only people with mental disorders experience auditory hallucinations. Moreover, these voices are not always angry. There is a very active Society of Hearing Voices, led by Marius Romm and Sandra Escher. This movement speaks to the positive aspects of voices and fights against their stigmatization.

Many people who hear voices live active and happy lives, so we can’t assume that voices are always bad. They are often associated with aggressive, paranoid, and anxious behaviors of the mentally ill, but these behaviors may be the result of their emotional distress, not the voices themselves. Perhaps not surprisingly, the anxiety and paranoia that are often at the core of mental illness are manifested in what voices say.

It is worth noting that eat Many people without a psychiatric diagnosis report hearing voices. For these people, voices can be a positive experience as they calm or even guide them in life. Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has thoroughly investigated this phenomenon. She found a group of healthy and well-functioning people hearing voices. They described their “voices” as something positive, helpful, and self-assurance.

Treatment of hallucinations

People diagnosed with schizophrenia are usually treated with "antipsychotic" medications. These medications block postsynaptic dopamine receptors in an area of the brain called the striatum. Antipsychotics are effective for many patients, and as a result of treatment, their psychotic symptoms are reduced to some extent, especially auditory hallucinations and manias.

However, the symptoms of many patients do not seem to respond well to antipsychotics. Approximately 25-30% of patients who hear voices, drugs are almost not affected. Antipsychotics also have serious side effects, so these medications are not suitable for all patients.

As for other treatments, There are many options for non-drug intervention. The degree of their effectiveness also varies. Example: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The use of CBT to treat psychosis is somewhat controversial, as quite a few researchers believe it has little effect on symptoms and overall outcome. There are some types of CBT designed specifically for patients who hear voices. These therapies usually aim to change the patient's attitude to the voice so that it is perceived as less negative and unpleasant. The effectiveness of this treatment is in question.

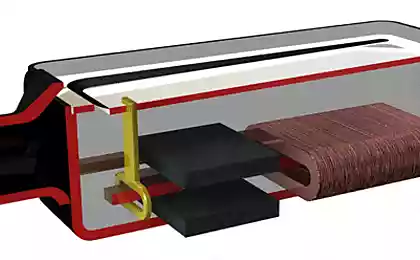

I'm currently leading a study at King's College London in which we're trying to see if we can teach patients to self-regulate neural activity in the auditory cortex.

This is achieved by “reverse neural communication in real-time MRI.” An MRI scanner is used to measure the signal coming from the auditory cortex. This signal is then sent back to the patient via a visual interface that the patient must learn to control (i.e., move the lever up and down). Eventually, we expect to be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control their auditory cortex activity, which could allow them to control their voices more effectively. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months.

Population prevalence

Around 24 million people around the world are living with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and about 60% or 70% of them have heard voices at some point. Across the population, between 5% and 10% of people without a psychiatric diagnosis have also heard voices at some point in their lives. Most of us have ever thought that someone calls us by name, and then it turns out that there is no one around. So there is evidence that hallucinations may not be accompanied by schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. Auditory hallucinations are more common than we think, although exact epidemiological statistics are difficult to pin down.

The most famous person to hear voices was probably Joan of Arc. From modern history, one can recall Sid Barrett, the founder of Pink Floyd, who suffered from schizophrenia and heard voices. However, again, many people without a psychiatric diagnosis hear voices but perceive them very positively. They can draw inspiration from their voices for art. Some, for example, experience musical hallucinations. It can be a kind of vivid auditory images, or just a kind of them – these people hear music very clearly in their heads. Scientists are not very sure if this equates to hallucinations.

Unanswered questions

Science does not have a clear answer to the question of what happens in the brain when a person hears voices. Another problem is that researchers don’t yet know why people perceive them as aliens coming from an external source. It is important to try to understand the phenomenological aspect of what people who hear voices experience.

For example, when people get tired or take stimulants, they may experience hallucinations, but do not necessarily perceive them as coming from outside sources.

The question is why people lose their sense of action when they hear voices. Even if we think that the reason for auditory hallucinations is the excessive activity of the auditory cortex, why do people still believe that the voice of God or a secret agent or aliens is speaking to them? It is also important to understand the belief systems that people build around their voices.

The content of auditory hallucinations and its source is another problem: Do these voices come from inner speech, or are they stored memories? It is safe to say that this sensory experience involves activation of the auditory cortex in the speech and language areas. It tells us nothing about the emotional content of these voices, which can often be negative. From this, in turn, it follows that there may be a problem in the brain when processing emotional information.

Also interesting: Seven mental hallucinations. Blocks of conscious management

Scientists about the brain: the best TED lectures with Russian voiceover

In addition, two people can experience hallucinations very differently, which means that the brain mechanisms involved can be quite different. published

Credit Paul Allen

Translated by Kirill Kozlovsky

Source: vk.com/public80512191?w=page-80512191_51115432