997

Germans in Soviet captivity

The ability to forgive is peculiar Russian. Still, how this property affects the soul - especially when you hear about it from the lips of yesterday's enemy ...

Letters former German prisoners of war.

I belong to the generation that experienced the Second World War. In July 1943, I became a soldier of the Wehrmacht, but because of the long training came to the German-Soviet front only in January 1945, which at that time was held on the territory of East Prussia. Then the German troops had had no chance in resisting the Soviet army. March 26, 1945 I was in Soviet captivity. I was in the camps in Kohli-Jarve in Estonia, in Vinogradov at Moscow, he worked in a coal mine in Stalinogorsk (today - Novomoskovsk).

Continued under the cut ...

We were always treated as human beings. We were able to leisure centers, medical care was provided to us. November 2, 1949, after 4, 5 years of captivity, I was released, he was released physically and spiritually healthy. I know that unlike my experience in Soviet captivity, Soviet prisoners of war in Germany, lived very differently. Hitler treated the majority of Soviet prisoners of war is very cruel. For a cultural nation, as always, are the Germans, with so many famous poets, composers and scholars, such treatment was inhumane and shameful act. After returning home, many former Soviet prisoners of war waiting for compensation from Germany, but did not wait. This is particularly outrageous! I hope that my modest donation I made a small contribution to mitigating this moral injury.

Hans Moezer

Fifty years ago, on 21 April 1945, during fierce fighting over Berlin, I fell into Soviet captivity. This date and the attendant circumstances were for my subsequent life of paramount importance. Today, after half a century, I look back now as a historian: the subject of this view in the past has been myself.

By the day of my captivity I had just celebrated his seventeenth birthday. Through Labor Front, we were called to the Wehrmacht, and ranked as the 12th Army, the so-called "Army of Ghosts". After April 16, 1945 the Soviet Army launched "Operation" Berlin "," we are literally thrown to the front.

The capture was for me and my young comrades a strong shock to this situation because we were completely unprepared. And nothing about Russia and Russian we knew nothing. This shock was also because so heavy that only once for the Soviet front line, we realized the severity of the losses suffered by our group. Out of a hundred people joined the fight in the morning, before noon, killing more than half. These experiences are painful memories in my life.

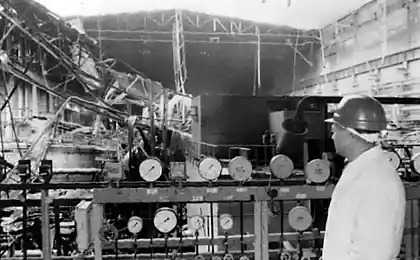

This was followed by the formation of trains with prisoners of war, who had taken us - with numerous intermediate stations - deep into the Soviet Union, on the Volga. The country needs German prisoners in the labor force, as was inactive during the war plants had to resume work. In Saratov, the beautiful city on the high bank of the Volga, again earned a sawmill, and in the "cement city" Volsky also located on the high bank of the river, I spent more than a year.

Our labor camp belonged to the cement factory "Bolshevik". Work at the plant has been for me, untrained eighteen-year senior high school student, unusually severe. German "kamerady" thus does not always help. People just needed to survive, to live to be sent home. In this endeavor German prisoners in the camp have developed their own, often cruel laws.

In February 1947, with me there was an accident at the quarry, after which I was no longer able to work. Six months later, I returned home disabled in Germany.

This is only the outer side of the case. During his stay in Saratov and Volsk then the conditions were very difficult. These conditions are often described in the publications of the German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union: the hunger and work. For me the big role played also the factor of climate change. In the summer, is on the Volga an unusually hot, I had to shovel cement plant from the red-hot furnace slag; in winter, when it is extremely cold, I was working in a quarry on the night shift.

I would like, before you take stock of my stay in the Soviet camp, described here is still something of experienced in captivity. And there were many impressions. I will cite only a few of them.

First - this is nature, majestic Volga along which every day we marched from the camp to the factory. Impressions of this vast river, the mother of Russian rivers are difficult to describe. One summer, when after the spring tide the river is widely rolled their waters, our Russian guards allowed us to jump into the river to wash the cement dust. Of course, the "officers" acted against the rules at the same time; but they, too, were human, we exchanged cigarettes, and they were a little older than me.

In October, we began the winter storms, and by mid-month paralyzed river ice cover. On the frozen river paved road, even trucks could move from one bank to another. And then, in mid-April, after six months of captivity, the ice, the Volga flowed freely again: the terrible roar broke the ice, and the river returns to its old channel. Our Russian guards were overjoyed: "The river is flowing again!" New year's time began.

The second part of the memories - is the relationship with the Soviet people. I have already described as humane were our guards. I can give you other examples of compassion, for example, one nurse in the fierce cold every morning, standing at the gates of the camp. Who did not have enough clothing to guard allowed winter to stay in the camp, despite the protests of the camp authorities. Or a Jewish doctor in the hospital that saved the life of more than one German, although they came as enemies. Finally, an elderly woman who during a lunch break at the station in Volsk, shyly give us pickles from his bucket. For us it was a real feast. Later, before you move, she went and crossed in front of each of us. Rus-mother, I have met in the late Stalinism, in 1946, on the Volga River.

When today, fifty years after my capture, I try to sum up, we find that captivity turned my life completely in a different direction, and defined my professional career.

His experience as a young man in Russia would not let me, and after his return to Germany. I had a choice - to dislodge from memory stolen my youth and never think of the Soviet Union, or to analyze all the experiences and thereby bring some biographical balance. I chose the second, infinitely more difficult path, not least under the influence of the supervisor of my doctoral work Paul Johansen.

As stated at the beginning, this hard way I look now. I ponder the achievements and stating the following: for decades in my lectures I tried to convey to my students' critical rethinking of experience to give a lively response. The closest disciples, I could help more qualified in their doctoral work and exams. Finally, I tied with Russian colleagues, especially in St. Petersburg, prolonged contact, which eventually grew into a lasting friendship.

Klaus Mayer

May 8, 1945 surrendered the remnants of the German 18th Army in Courland cauldron in Latvia. It was the long-awaited day. Our small 100 Wadden transmitter was designed to negotiate with the Red Army on the terms of surrender. All the weapons, equipment, transportation, radioavtomobili themselves radostantsii were, according to the Prussian carefully assembled in one place, in places surrounded by pine trees. Two days is not nothing happened. Then came the Soviet officers and carried us in two-story buildings. We spent the night in the cramped quarters on straw mattresses. Early in the morning of 11 May, we were built on hundreds, consider how old the distribution of their companies. It began foot march into captivity.

A Red Army soldier in front, one behind. So we walked in the direction of Riga to huge prefabricated camps prepared by the Red Army. There the officers were separated from ordinary soldiers. Guard searched taken with things. We were allowed to leave some underwear, socks, blankets, crockery and cutlery folding. Nothing more.

From Riga we walked unto the day is the endless march to the east, to the former Soviet-Latvian border in the direction Dunaburg. After each march we arrived at the next camp. The ritual was repeated: a search of personal belongings, distribution of food and night's sleep. On arrival at Dunaburg we were loaded into boxcars. The food was good: bread and American canned meat «Corned Beef». We went to the southeast. Those koto thought that we are going home, was surprised. After many days we arrived at Moscow's Baltic Station. Sotya truck, we proezali the city. It was already dark. Food Is one of us was able to do some recording.

Away from the city close to the village, consisting of a three-storey wooden houses, there was a big assembly camp so large that its outskirts were lost over the horizon. Tents and prisoners ... A week passed with good summer weather, Russian and American canned bread. After a morning calls of 150 to 200 prisoners were separated from the rest. We sat on the trucks. None of us knew where we were going. The path lay in the north-west. The last kilometers we drove through a birch forest on the dam. After a two-hour somewhere trip (or longer?), We were the target.

Forest camp consisted of three or four wooden barracks, located partly on the ground level. The door was located low on the level of a few steps down. Over the last hut he lived in the German camp commandant from East Prussia were the premises of tailors and shoemakers, doctor's office and a separate barracks for patients. The whole area is barely larger than a football pitch, was fenced with barbed wire. Intended to protect a little more comfortable wooden barracks. In the territory also has a booth to watch and a small kitchen. This place was for the next few months, and perhaps years, to become our new home. At the prompt return home it was unlikely.

In barakak stretched along the central aisle two rows of wooden double-decker bunks. Upon completion of the registration procedure difficult (we did not have with our soldiers' books), we placed on the benches filled with straw mattresses. Located on the top tier might get lucky. He was able to look out into the glazed window size like 25 x 25 centimeters.

Exactly at 6:00 was the rise. Then all ran to the washbasin. At an altitude of about 1, 70 meter starts tin gutter, smotrirovanny on wooden support. The water level went down about belly. In the months when there was no frost, the upper reservoir was filled with water. For washing had to turn a simple valve, after which the water poured or dripped on his head and upper body. After this procedure was repeated daily roll call on the parade ground. At exactly 7:00, we walked to the logging endless birch forests surrounding the camp. I can not remember that I had to cut some other tree, except for birch.

At the site we were waiting for our "bosses", civil civilian overseers. They distribute tools: saws and axes. Create groups of three: two prisoners felled tree, and a third collects leaves and unnecessary branches in one pile, and then burn. Particularly in wet weather it was a whole art. Of course, each prisoner was lighter. Along with a spoon, it's probably the most important thing in captivity. But using such a simple object consisting of flint, wick and a piece of iron could ignite sodden from the rain tree is often only after hours of effort. Incineration of wood applied to the daily rate. The norm itself consisted of two meters of felled wood stacked in a pile. Each wooden stump had to be two meters long and a minimum of 10 centimeters in diameter. With such primitive tools like blunt saws and axes, often consisting of only a few common pieces of iron welded together, could hardly fulfill a norm.

After the work pile tree climb "chiefs" and loaded into open trucks. In the afternoon the work was interrupted for half an hour. We were given watery cabbage soup. Those who could perform normal (due to hard work and malnutrition succeeded only slightly) was obtained in the evening in addition to the usual ration of 200 grams of wet bread, however good taste, a tablespoon of sugar and Zhmenya tobacco, and even porridge straight to cover the pan. One "calming": the power of our guards were not much better.

Winter 1945/46 biennium. It was very hard. We stopped up in clothes and boots wads of cotton wool. We cut down trees and put them in a staple to the moment when the temperature did not drop below 20 degrees below zero Celsius. If it gets cold, all the prisoners were in the camp.

One or two times a month have awakened at night. We got up from our straw mattresses, and drove the truck to the station, to which was about 10 kilometers. We saw a huge mountain forests. It was our fallen trees. Wood had to be loaded in covered wagons and sent in Tushino near Moscow. Mountain forests inspire us to a state of depression and fear. We had to bring the mountain to move. It was our job. What we still hold out? How long it will last? This night seemed endless to us. And when the day cars were fully loaded. The work was tedious. Two men carried on the shoulders of six-foot tree trunk to the car and then just pushes it without a lift in the open door of the car. Two particularly strong prisoners piled wood inside the car in staple. The car was filled. The turn of the next car. We covered the spotlight on a high pole. It was kind of surreal: the shadows of the tree trunks and the prisoners crawling like some fantastic wingless creatures. When falling to the ground the first rays of the sun, we walked back to the camp. This whole day has been for us the weekend.

One January night in 1946 I particularly etched in my memory. Frost was so strong that after the operation not start the engines of trucks. We had to walk on ice 10 or 12 kilometers from the camp. The full moon lit us. A group of 50-60 prisoners trudged, stumbling. People are increasingly moving away from one another. I could not distinguish the man in front. I thought it was the end. Until now, I do not know, I still managed to reach the camp.

Lesopoval. Day after day. Endless Winter. More and more prisoners feel mentally depressed. Salvation was recorded in the "trip." So we called the work in nearby farms and state farms. Hoe and shovel, we picked out of the frozen ground potatoes or beets. Many could not collect. But still collected evolved into a pan and heated. Instead of water used by the melting snow. Our guard was eating cooked with us. Nothing is thrown away. Cleaning gathered in secret from inspectors at the entrance to the camp swept the territory and after obtaining the evening bread and sugar pozharivalis in the barracks on the two red-hot iron stove. It was a kind of "carnival" food in the dark. Most of the prisoners at that time were already asleep. And we sat, soaking exhausted bodies like a warm sweet syrup.

When I look at the elapsed time from the height of past years, I can say that I have never and nowhere, in any place of the USSR did not notice such thing as hatred of the Germans. It is amazing. After all, we were German prisoners, representatives of the people, who for centuries twice plunged Russia into war. The second war was unprecedented in terms of violence, terror and crime. If there were signs of any charges, they never were "collective", addressed to all the German people.

In early May 1946, I worked in a group of 30 prisoners of war from our camp in one of the farms. Long, strong, has recently grown tree trunks, intended for the construction of houses had to be loaded on trucks cooked. And then it happened. The tree trunk was carried on the shoulders. I was on the "wrong" side. When loading the barrel into the back of the truck, my head was squeezed between two trunks. I was lying unconscious in the back of the machine. From the ears, mouth and nose bleeding. The truck took me back to the camp. At this point, my memory rejected. Then I remembered nothing.

The camp doctor, an Austrian, was a Nazi. This all knew. He did not have the necessary medicines and dressing materials. His only tools were nail scissors. The doctor said immediately: "fracture of the skull base.

Source:

Letters former German prisoners of war.

I belong to the generation that experienced the Second World War. In July 1943, I became a soldier of the Wehrmacht, but because of the long training came to the German-Soviet front only in January 1945, which at that time was held on the territory of East Prussia. Then the German troops had had no chance in resisting the Soviet army. March 26, 1945 I was in Soviet captivity. I was in the camps in Kohli-Jarve in Estonia, in Vinogradov at Moscow, he worked in a coal mine in Stalinogorsk (today - Novomoskovsk).

Continued under the cut ...

We were always treated as human beings. We were able to leisure centers, medical care was provided to us. November 2, 1949, after 4, 5 years of captivity, I was released, he was released physically and spiritually healthy. I know that unlike my experience in Soviet captivity, Soviet prisoners of war in Germany, lived very differently. Hitler treated the majority of Soviet prisoners of war is very cruel. For a cultural nation, as always, are the Germans, with so many famous poets, composers and scholars, such treatment was inhumane and shameful act. After returning home, many former Soviet prisoners of war waiting for compensation from Germany, but did not wait. This is particularly outrageous! I hope that my modest donation I made a small contribution to mitigating this moral injury.

Hans Moezer

Fifty years ago, on 21 April 1945, during fierce fighting over Berlin, I fell into Soviet captivity. This date and the attendant circumstances were for my subsequent life of paramount importance. Today, after half a century, I look back now as a historian: the subject of this view in the past has been myself.

By the day of my captivity I had just celebrated his seventeenth birthday. Through Labor Front, we were called to the Wehrmacht, and ranked as the 12th Army, the so-called "Army of Ghosts". After April 16, 1945 the Soviet Army launched "Operation" Berlin "," we are literally thrown to the front.

The capture was for me and my young comrades a strong shock to this situation because we were completely unprepared. And nothing about Russia and Russian we knew nothing. This shock was also because so heavy that only once for the Soviet front line, we realized the severity of the losses suffered by our group. Out of a hundred people joined the fight in the morning, before noon, killing more than half. These experiences are painful memories in my life.

This was followed by the formation of trains with prisoners of war, who had taken us - with numerous intermediate stations - deep into the Soviet Union, on the Volga. The country needs German prisoners in the labor force, as was inactive during the war plants had to resume work. In Saratov, the beautiful city on the high bank of the Volga, again earned a sawmill, and in the "cement city" Volsky also located on the high bank of the river, I spent more than a year.

Our labor camp belonged to the cement factory "Bolshevik". Work at the plant has been for me, untrained eighteen-year senior high school student, unusually severe. German "kamerady" thus does not always help. People just needed to survive, to live to be sent home. In this endeavor German prisoners in the camp have developed their own, often cruel laws.

In February 1947, with me there was an accident at the quarry, after which I was no longer able to work. Six months later, I returned home disabled in Germany.

This is only the outer side of the case. During his stay in Saratov and Volsk then the conditions were very difficult. These conditions are often described in the publications of the German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union: the hunger and work. For me the big role played also the factor of climate change. In the summer, is on the Volga an unusually hot, I had to shovel cement plant from the red-hot furnace slag; in winter, when it is extremely cold, I was working in a quarry on the night shift.

I would like, before you take stock of my stay in the Soviet camp, described here is still something of experienced in captivity. And there were many impressions. I will cite only a few of them.

First - this is nature, majestic Volga along which every day we marched from the camp to the factory. Impressions of this vast river, the mother of Russian rivers are difficult to describe. One summer, when after the spring tide the river is widely rolled their waters, our Russian guards allowed us to jump into the river to wash the cement dust. Of course, the "officers" acted against the rules at the same time; but they, too, were human, we exchanged cigarettes, and they were a little older than me.

In October, we began the winter storms, and by mid-month paralyzed river ice cover. On the frozen river paved road, even trucks could move from one bank to another. And then, in mid-April, after six months of captivity, the ice, the Volga flowed freely again: the terrible roar broke the ice, and the river returns to its old channel. Our Russian guards were overjoyed: "The river is flowing again!" New year's time began.

The second part of the memories - is the relationship with the Soviet people. I have already described as humane were our guards. I can give you other examples of compassion, for example, one nurse in the fierce cold every morning, standing at the gates of the camp. Who did not have enough clothing to guard allowed winter to stay in the camp, despite the protests of the camp authorities. Or a Jewish doctor in the hospital that saved the life of more than one German, although they came as enemies. Finally, an elderly woman who during a lunch break at the station in Volsk, shyly give us pickles from his bucket. For us it was a real feast. Later, before you move, she went and crossed in front of each of us. Rus-mother, I have met in the late Stalinism, in 1946, on the Volga River.

When today, fifty years after my capture, I try to sum up, we find that captivity turned my life completely in a different direction, and defined my professional career.

His experience as a young man in Russia would not let me, and after his return to Germany. I had a choice - to dislodge from memory stolen my youth and never think of the Soviet Union, or to analyze all the experiences and thereby bring some biographical balance. I chose the second, infinitely more difficult path, not least under the influence of the supervisor of my doctoral work Paul Johansen.

As stated at the beginning, this hard way I look now. I ponder the achievements and stating the following: for decades in my lectures I tried to convey to my students' critical rethinking of experience to give a lively response. The closest disciples, I could help more qualified in their doctoral work and exams. Finally, I tied with Russian colleagues, especially in St. Petersburg, prolonged contact, which eventually grew into a lasting friendship.

Klaus Mayer

May 8, 1945 surrendered the remnants of the German 18th Army in Courland cauldron in Latvia. It was the long-awaited day. Our small 100 Wadden transmitter was designed to negotiate with the Red Army on the terms of surrender. All the weapons, equipment, transportation, radioavtomobili themselves radostantsii were, according to the Prussian carefully assembled in one place, in places surrounded by pine trees. Two days is not nothing happened. Then came the Soviet officers and carried us in two-story buildings. We spent the night in the cramped quarters on straw mattresses. Early in the morning of 11 May, we were built on hundreds, consider how old the distribution of their companies. It began foot march into captivity.

A Red Army soldier in front, one behind. So we walked in the direction of Riga to huge prefabricated camps prepared by the Red Army. There the officers were separated from ordinary soldiers. Guard searched taken with things. We were allowed to leave some underwear, socks, blankets, crockery and cutlery folding. Nothing more.

From Riga we walked unto the day is the endless march to the east, to the former Soviet-Latvian border in the direction Dunaburg. After each march we arrived at the next camp. The ritual was repeated: a search of personal belongings, distribution of food and night's sleep. On arrival at Dunaburg we were loaded into boxcars. The food was good: bread and American canned meat «Corned Beef». We went to the southeast. Those koto thought that we are going home, was surprised. After many days we arrived at Moscow's Baltic Station. Sotya truck, we proezali the city. It was already dark. Food Is one of us was able to do some recording.

Away from the city close to the village, consisting of a three-storey wooden houses, there was a big assembly camp so large that its outskirts were lost over the horizon. Tents and prisoners ... A week passed with good summer weather, Russian and American canned bread. After a morning calls of 150 to 200 prisoners were separated from the rest. We sat on the trucks. None of us knew where we were going. The path lay in the north-west. The last kilometers we drove through a birch forest on the dam. After a two-hour somewhere trip (or longer?), We were the target.

Forest camp consisted of three or four wooden barracks, located partly on the ground level. The door was located low on the level of a few steps down. Over the last hut he lived in the German camp commandant from East Prussia were the premises of tailors and shoemakers, doctor's office and a separate barracks for patients. The whole area is barely larger than a football pitch, was fenced with barbed wire. Intended to protect a little more comfortable wooden barracks. In the territory also has a booth to watch and a small kitchen. This place was for the next few months, and perhaps years, to become our new home. At the prompt return home it was unlikely.

In barakak stretched along the central aisle two rows of wooden double-decker bunks. Upon completion of the registration procedure difficult (we did not have with our soldiers' books), we placed on the benches filled with straw mattresses. Located on the top tier might get lucky. He was able to look out into the glazed window size like 25 x 25 centimeters.

Exactly at 6:00 was the rise. Then all ran to the washbasin. At an altitude of about 1, 70 meter starts tin gutter, smotrirovanny on wooden support. The water level went down about belly. In the months when there was no frost, the upper reservoir was filled with water. For washing had to turn a simple valve, after which the water poured or dripped on his head and upper body. After this procedure was repeated daily roll call on the parade ground. At exactly 7:00, we walked to the logging endless birch forests surrounding the camp. I can not remember that I had to cut some other tree, except for birch.

At the site we were waiting for our "bosses", civil civilian overseers. They distribute tools: saws and axes. Create groups of three: two prisoners felled tree, and a third collects leaves and unnecessary branches in one pile, and then burn. Particularly in wet weather it was a whole art. Of course, each prisoner was lighter. Along with a spoon, it's probably the most important thing in captivity. But using such a simple object consisting of flint, wick and a piece of iron could ignite sodden from the rain tree is often only after hours of effort. Incineration of wood applied to the daily rate. The norm itself consisted of two meters of felled wood stacked in a pile. Each wooden stump had to be two meters long and a minimum of 10 centimeters in diameter. With such primitive tools like blunt saws and axes, often consisting of only a few common pieces of iron welded together, could hardly fulfill a norm.

After the work pile tree climb "chiefs" and loaded into open trucks. In the afternoon the work was interrupted for half an hour. We were given watery cabbage soup. Those who could perform normal (due to hard work and malnutrition succeeded only slightly) was obtained in the evening in addition to the usual ration of 200 grams of wet bread, however good taste, a tablespoon of sugar and Zhmenya tobacco, and even porridge straight to cover the pan. One "calming": the power of our guards were not much better.

Winter 1945/46 biennium. It was very hard. We stopped up in clothes and boots wads of cotton wool. We cut down trees and put them in a staple to the moment when the temperature did not drop below 20 degrees below zero Celsius. If it gets cold, all the prisoners were in the camp.

One or two times a month have awakened at night. We got up from our straw mattresses, and drove the truck to the station, to which was about 10 kilometers. We saw a huge mountain forests. It was our fallen trees. Wood had to be loaded in covered wagons and sent in Tushino near Moscow. Mountain forests inspire us to a state of depression and fear. We had to bring the mountain to move. It was our job. What we still hold out? How long it will last? This night seemed endless to us. And when the day cars were fully loaded. The work was tedious. Two men carried on the shoulders of six-foot tree trunk to the car and then just pushes it without a lift in the open door of the car. Two particularly strong prisoners piled wood inside the car in staple. The car was filled. The turn of the next car. We covered the spotlight on a high pole. It was kind of surreal: the shadows of the tree trunks and the prisoners crawling like some fantastic wingless creatures. When falling to the ground the first rays of the sun, we walked back to the camp. This whole day has been for us the weekend.

One January night in 1946 I particularly etched in my memory. Frost was so strong that after the operation not start the engines of trucks. We had to walk on ice 10 or 12 kilometers from the camp. The full moon lit us. A group of 50-60 prisoners trudged, stumbling. People are increasingly moving away from one another. I could not distinguish the man in front. I thought it was the end. Until now, I do not know, I still managed to reach the camp.

Lesopoval. Day after day. Endless Winter. More and more prisoners feel mentally depressed. Salvation was recorded in the "trip." So we called the work in nearby farms and state farms. Hoe and shovel, we picked out of the frozen ground potatoes or beets. Many could not collect. But still collected evolved into a pan and heated. Instead of water used by the melting snow. Our guard was eating cooked with us. Nothing is thrown away. Cleaning gathered in secret from inspectors at the entrance to the camp swept the territory and after obtaining the evening bread and sugar pozharivalis in the barracks on the two red-hot iron stove. It was a kind of "carnival" food in the dark. Most of the prisoners at that time were already asleep. And we sat, soaking exhausted bodies like a warm sweet syrup.

When I look at the elapsed time from the height of past years, I can say that I have never and nowhere, in any place of the USSR did not notice such thing as hatred of the Germans. It is amazing. After all, we were German prisoners, representatives of the people, who for centuries twice plunged Russia into war. The second war was unprecedented in terms of violence, terror and crime. If there were signs of any charges, they never were "collective", addressed to all the German people.

In early May 1946, I worked in a group of 30 prisoners of war from our camp in one of the farms. Long, strong, has recently grown tree trunks, intended for the construction of houses had to be loaded on trucks cooked. And then it happened. The tree trunk was carried on the shoulders. I was on the "wrong" side. When loading the barrel into the back of the truck, my head was squeezed between two trunks. I was lying unconscious in the back of the machine. From the ears, mouth and nose bleeding. The truck took me back to the camp. At this point, my memory rejected. Then I remembered nothing.

The camp doctor, an Austrian, was a Nazi. This all knew. He did not have the necessary medicines and dressing materials. His only tools were nail scissors. The doctor said immediately: "fracture of the skull base.

Source: