288

What it means to do the right thing and why it is so difficult

The Crossroads of Ethical Decisions: Visualizing Moral Choices in the Modern World

In the personal values of any person there are truths and errors, virtues and vices - none of these elements can be completely eliminated. Moral complexity is an integral part of human existence, and finding the right thing becomes one of life’s greatest challenges.

The Paradox of Ethical Choice: Why It’s So Hard to Determine the Right One

Every day we face dozens of decisions. Most of them are taken automatically, based on formed habits and attitudes. However, when it comes to meaningful ethical choices, many of us experience what psychologists call a moral dilemma. Moral dilemmas arise when different values, principles, or obligations collide, and there is no unequivocally right solution.

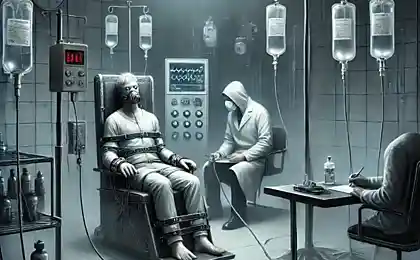

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle spoke of virtue as the “golden mean” between extremes. For example, courage is the middle ground between recklessness and cowardice. But where exactly is that middle ground? For different people and in different situations, it can be different. Current research in neuroethics shows that our brains activate different neural circuits when faced with moral dilemmas, often leading to internal conflict.

The main reasons for the complexity of ethical choice:

- Conflict of values When equally important principles require opposite actions

- Incomplete information Inability to foresee all the consequences of your actions

- Cultural and social context What is right in one culture can be condemned in another.

- Emotional influence Our emotions can distort our rational assessment of the situation.

- Cognitive distortions Systematic errors in thinking that affect our perception

Contemporary research in moral psychology conducted by Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues demonstrates that moral judgments are often the result not of rational analysis, but of rapid intuitive reactions, which we then try to justify logically. This concept is known as “intuitive ethics” or “moral intuition.”

Neuroethics: Visualizing brain activity in moral decision-making

Cognitive distortions and ethical choices

Psychologists identify dozens of cognitive biases that influence our decisions. These mental filters are often invisible to us, but can radically affect our ability to make ethically informed decisions.

Key cognitive biases affecting moral choices:

- Confirmation distortion The tendency to seek and interpret information to confirm existing beliefs

- Halo effect transfer of a positive impression of one quality of a person to his personality as a whole

- Fundamental attribution error The tendency to explain the behavior of other people by their personality traits, ignoring situational factors

- Homeland swamp effect Preference for “ours” and bias against “aliens”

- Hyperbolic depreciation Overestimating immediate benefits and underestimating long-term consequences

According to a study published in the journal Psychological Science, people are more likely to forgive themselves moral misconduct than others, demonstrating a so-called “double standard of morality.” This cognitive distortion is called “egocentric blindness” and manifests itself in the fact that we find excuses for our own unethical actions, but judge the actions of other people more strictly.

“It is easy to see a mote in another’s eye, but not to see a log in your own.” This ancient wisdom accurately describes our moral selectivity.

Five Steps to Conscious Ethical Choices

Despite all the challenges, there are practical strategies that can help us make better ethical decisions. These approaches do not guarantee the “right” choice, but they can minimize the influence of prejudice and become more aware of one’s own values.

1. Practice Moral Reflection

Set aside time regularly to reflect on your actions and their alignment with your core values. Ask yourself: “What drives my decisions?”, “Do my actions correspond to who I want to be?”, “How would I appreciate such an act if another person did it?”

2. Develop empathy.

Try to look at the situation from the point of view of all parties involved. Studies show that people with developed empathy make more balanced ethical decisions. Perspective techniques – mentally putting yourself in the other person’s shoes – can greatly expand your understanding of a situation.

3. Use ethical frameworks

When faced with complex moral dilemmas, it is useful to apply classical ethical approaches: deontology (evaluation of actions in terms of duties and rights), utilitarianism (estimation of consequences for the maximum good), ethics of virtue (orientation on character and personal qualities).

4. Consult with moral authorities

Discuss complex ethical decisions with people whose values and judgments you respect. Dialogue often helps to see aspects of a problem that you may not have noticed.

5. Remember to look from the outside.

Ask yourself, “How would I feel if my actions were on the front page of the paper?” This thought experiment, proposed by philosopher Immanuel Kant, helps to assess the universality of our ethical principles.

Neuroscientist Sam Harris, in his work The Moral Landscape, proposes to consider ethical choices in terms of the well-being of conscious beings. According to his approach, actions that promote prosperity and well-being are morally correct, and actions that increase suffering are wrong. While this approach has its limitations, it offers a practical basis for ethical reflection.

Balance of Ethical Systems: Visualizing the Interconnection of Different Moral Concepts

Practical recommendations for overcoming moral dilemmas

Specific life hacks for ethical decision-making:

- Pre-codification method Define your principles in advance for different types of situations until you are emotionally influenced.

- Technique "in 5 years" Ask yourself if this decision will make a difference in 5 years and how you will feel about it.

- Journal of Ethical Solutions Keep records of your moral choices and their consequences to learn from experience

- The three-chair method Imagine three perspectives: your own, another person, and a neutral observer.

- Reputation rule Make only those decisions that will not destroy your trust if they become known to others.

- Method of moral mathematics Decompose the complex solution into components and rate each on a scale from -10 to +10

- The principle of least regret Choose the action you least regret, even if it’s not perfect.

Studies show that moral fatigue is a real psychological phenomenon. Constant ethical decision-making depletes our cognitive resources, which can lead to “moral disconnection” – a condition where a person temporarily loses the ability to make ethically based decisions. To avoid this, it is important to practice self-care and consciously restore your psychological resources.

Signs of moral fatigue:

- A constant sense of internal conflict

- Cynicism and Declining Empathy

- Simplifying complex moral situations

- Postponing important decisions

- Emotional exhaustion when thinking about values

Why ‘Imperfect’ Decisions Are Sometimes Necessary

The pursuit of moral perfection can paradoxically lead to ethical problems. Psychologists call this phenomenon “moral perfectionism.” In the real world, we are often forced to choose not between absolute good and evil, but between different compromises, each with its own flaws.

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin argued in his work on value pluralism that many fundamental values are incompatible with each other and cannot be fully realized simultaneously. For example, freedom often conflicts with security, justice with mercy, and the individual with the public good. This means that finding the “perfect” solution may be conceptually impossible.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing.” - Edmund Burke.

Accepting the imperfection of our moral decisions is an important step toward ethical maturity. This does not mean moral relativism or abandonment of principles. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of the complexity of the world and a willingness to act even when the perfect solution is not available.

Research on psychological resilience suggests that people who are able to accept moral complexity and ambiguity are less prone to black-and-white thinking and more successful at resolving ethical conflicts. They also exhibit greater psychological flexibility and lower levels of moral stress.

Conclusion: Towards ethical wisdom

Doing the right thing is difficult not only because of external circumstances, but also because of the fundamental nature of morality, which often involves balancing conflicting values. There are truths and errors, virtues and vices, and none of these elements can be completely eliminated.

Ethical wisdom consists not in seeking absolute answers, but in developing the capacity for moral reflection, empathy, and informed decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. We can strive for moral growth by acknowledging our imperfections and constantly working to broaden our ethical horizon.

Rather than looking for a universal moral algorithm that applies to all situations, it is more productive to develop ethical intuition—the ability to recognize and respond to moral aspects of a situation accordingly. It requires practice, reflection and openness to different perspectives.

And remember, the very fact that you think about the rightness of your actions is already a step in the right direction. Moral sensitivity is a muscle that strengthens with every conscious ethical choice.

Glossary

A moral dilemma

A situation in which a person must choose between two or more actions, each of which has morally undesirable consequences or contradicts important ethical principles.

Deontology

Ethical theory, according to which the morality of an action is determined by its compliance with certain duties, rules or principles, regardless of the consequences.

Utilitarianism

The ethical theory that right is the action that leads to the greatest happiness or good for the greatest number of people.

Virtue ethics

An approach to ethics that emphasizes the role of character and virtues, rather than rules or consequences, in determining the moral value of an action.

Cognitive distortion

A systematic error in thinking that affects judgments and decisions, often acting beyond conscious awareness.

Moral perfectionism

Striving for absolute moral perfection, which can lead to inaction or excessive self-criticism due to the inability to achieve ideal results.

Value pluralism

A philosophical concept that holds that there are many fundamental values that may be incompatible with each other and defy a single hierarchy or system.

Moral intuition

A rapid, automatic emotional response to moral situations that precedes conscious reasoning.

Neuroethics

An interdisciplinary field studying the neurobiological foundations of moral judgment and ethical behavior.

Moral fatigue

A psychological state of exhaustion resulting from the constant making of complex ethical decisions that can reduce the capacity for moral judgment.

11 situations that cause feelings of guilt, and how to cope with them

6 habits that will help you stop reacting to problems