188

Watching and Punishing: John Ronson on Bullying in the Digital World

John Ronson’s new book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, explores the phenomenon of online bullying and our attitude toward shame. Ronson himself recently became a victim of an information bot. In the process, the journalist was struck by how vindictive comments he received from users about the story. Why does social media easily turn us into wardens? We have translated a few quotes from this book.

At the dawn of Twitter, no one was ever bullied. We lived like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and yes, we probably talked a lot. A friend of mine once said, “Facebook is a place where you lie to your friends, and on Twitter you tell them the truth.” Tweeting with nice people I didn’t know, I was able to get through some hard times in my own home. But then we became proud that now with an easy hand we can cheat even millionaires like Rupert Murdoch and Donald Trump. They started Twitter accounts, and we started monitoring their misconduct around the clock. Or rather, not even for misdeeds, but for their reservations. We were overwhelmed with rage at the fact that other people sometimes carry some kind of nonsense. And often our rage was completely out of proportion to the delirium they were carrying. But in attacking another Twitter offender, we felt not as journalists or critics, but as those with the power and right to punish. So in those days when there was no one to punish, the soul was empty.

I was deeply struck by the brutality with which people demanded that John Lehrer apologize after the scandal over the falsification of quotes in his book. But these people were not some infinitely distant crowd for me. I used to be a part of it, too. I was blithely bullying online for about a year. Do I remember those who were my online victims? Hardly. Truth be told, I have very bleak memories of what they did to deserve my wrath.

It turned out that the concept of “group madness” was invented in France by a doctor named Gustave Le Bon. He believed that when people fall into a group, they completely lose control of themselves. Our will evaporates. And at that point, we can direct our anger at anyone, like Justin Sacco, who tweeted badly about HIV in Africa.

As you know, in France, quite early began to treat the crowd with caution. In 1853, when Le Bon was 12 years old, Napoleon III ordered the town planner Hausmann to demolish the Parisian medieval nooks and build wide boulevards in their place to easier control the flow of people. But his idea did not work, and in 1871 the uprising began.

Le Bon was very worried and sympathetic to the French ruling elite (which, incidentally, had little sympathy for Le Bon himself) and was extremely glad when the army struck the rebels and killed 25,000 people. Could he have scientifically proven that the uprising had no objective basis and was merely a mass insanity? Perhaps such a theory could become a pass to the upper world for him, because this was exactly what they wanted to hear.

Every time I told someone I was writing a book about shame, many people asked me to write about why today’s young people had lost shame. A famous architect told me that. And one radio host also suggested that all this is due to the loss of religion. Of course, I can understand where these thoughts come from. But today, if the news reports that a priest has been to a prostitute, it's hardly going to bother anyone. Many people put a lot of effort into making sure that men can come out clean from a variety of sex scandals. Shame and shame have not disappeared from society. It's just shameful to do other things now. It is becoming increasingly difficult to predict which ones.

Because the decision about what's shameful and what's not is made by the Twitter crowd. It's where we decide who hears the destruction and doesn't ask the legal system for advice. This fact makes us unpredictable and dangerous.

Psychiatrist James Gilligan spent his life studying how shame corrodes the inner world of prisoners. In the 1970s, there was an outbreak of violence in American prisons: suicides and murders in the walls of the colonies sharply increased. Gilligan was sent to study this phenomenon. In almost every conversation, the inmates told him they had long felt dead. Shame – aggravated by the disdainful attitude of the guards – ate them so much that they no longer had any emotions. And so they started cutting themselves or others. To see if they're capable of any more feelings.

In 1991, James Gilligan began collaborating with Harvard University, attracting professors to give free lectures in prisons. After all, what can help people regain their dignity, but education? At the same time there was a campaign of Governor William Weld. At a press conference, journalists asked him how he felt about Gilligan’s initiative. Oeld replied: “We should stop with this project — we should not give prisoners free higher education. Otherwise, those people who do not have enough money for it will commit crimes to attend university courses for free.” Needless to say, that's where Gilligan's educational program ended?

In the early 1990s, search engines sorted information only by the number of times the keywords were searched for on a given page. For example, if I scored my name on AltaVista or HotBot, the first line would pop up a page where my name would just be repeated a million times. (This would be my favorite site, but I think it would have a few other fans.)

And then two Stanford students -- Larry Page and Sergey Brin -- came up with a different concept. They decided it was time to make a new search engine that would rank websites by their popularity. If someone links to your page, you get points. After all, a reference is like a quote is a sign of respect. They named their new system PageRank after Larry Page.

Today, there are agencies that restore the “honor” of customers who were bullied on the Internet. They are creating new profiles for victims on Twitter, LinkedIn and Tumblr, because these sites have an innate high PageRank rating. The algorithm throws them up as the most popular. But the problem with Google is that the algorithm is constantly changing. It seems that preference is given to old sites or, conversely, new ones – and everything in the middle (over 12 weeks) is poorly indexed.

Most of all, clients of such agencies are afraid of reversion. For them, there is nothing scarier in the world than seeing links to good resources roll back to the second page, and the first resurfaces the old horror.

Once upon a time there was a saying on the Internet that as soon as you compare something to Nazism in an argument, you immediately lose the argument. Perhaps the same can be said about the Stasi, the secret police in the GDR.

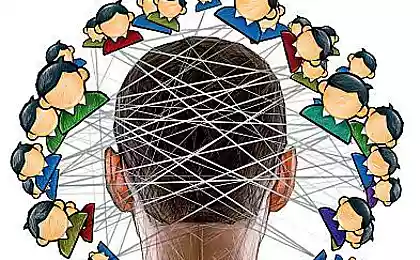

The horror of the Stasi was not only that there was physical violence. The main goal of the Stasi was to create the largest network of guards over each other in the history of mankind. And perhaps this example can teach us something about modern digital society.

In 2003, 14 years after the destruction of the Stasi and three years before the invention of Twitter, Anna Funder wrote the book Stasiland.

Of course, no secret agent intercepted Justin Sacco's thoughts. She tweeted them herself, naively believing that Twitter is a safe place to tell strangers the truth about yourself. And this idealistic experiment ended pretty badly for her.

Funder was able to interview a former Stasi official whose job was to recruit new whistleblowers. Funder tried to ask him why people agreed to work for the Stasi, when they were so poorly paid for it, and there were so many jobs. Most people said yes simply because they wanted to feel important, because every week the Stasi listened to their stories about their neighbors.

I was struck by the condescension with which a former secret police officer spoke of his informants. Perhaps the same can be said about Twitter users. Social media gives voice to previously voiceless people - that's egalitarianism at its best. But the conclusion that psychologists came to when they studied the success of the Stasi recruiters was, “People went to work as informants because they just wanted to make sure their neighbors were doing the right thing.”

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru

At the dawn of Twitter, no one was ever bullied. We lived like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and yes, we probably talked a lot. A friend of mine once said, “Facebook is a place where you lie to your friends, and on Twitter you tell them the truth.” Tweeting with nice people I didn’t know, I was able to get through some hard times in my own home. But then we became proud that now with an easy hand we can cheat even millionaires like Rupert Murdoch and Donald Trump. They started Twitter accounts, and we started monitoring their misconduct around the clock. Or rather, not even for misdeeds, but for their reservations. We were overwhelmed with rage at the fact that other people sometimes carry some kind of nonsense. And often our rage was completely out of proportion to the delirium they were carrying. But in attacking another Twitter offender, we felt not as journalists or critics, but as those with the power and right to punish. So in those days when there was no one to punish, the soul was empty.

I was deeply struck by the brutality with which people demanded that John Lehrer apologize after the scandal over the falsification of quotes in his book. But these people were not some infinitely distant crowd for me. I used to be a part of it, too. I was blithely bullying online for about a year. Do I remember those who were my online victims? Hardly. Truth be told, I have very bleak memories of what they did to deserve my wrath.

It turned out that the concept of “group madness” was invented in France by a doctor named Gustave Le Bon. He believed that when people fall into a group, they completely lose control of themselves. Our will evaporates. And at that point, we can direct our anger at anyone, like Justin Sacco, who tweeted badly about HIV in Africa.

As you know, in France, quite early began to treat the crowd with caution. In 1853, when Le Bon was 12 years old, Napoleon III ordered the town planner Hausmann to demolish the Parisian medieval nooks and build wide boulevards in their place to easier control the flow of people. But his idea did not work, and in 1871 the uprising began.

Le Bon was very worried and sympathetic to the French ruling elite (which, incidentally, had little sympathy for Le Bon himself) and was extremely glad when the army struck the rebels and killed 25,000 people. Could he have scientifically proven that the uprising had no objective basis and was merely a mass insanity? Perhaps such a theory could become a pass to the upper world for him, because this was exactly what they wanted to hear.

Every time I told someone I was writing a book about shame, many people asked me to write about why today’s young people had lost shame. A famous architect told me that. And one radio host also suggested that all this is due to the loss of religion. Of course, I can understand where these thoughts come from. But today, if the news reports that a priest has been to a prostitute, it's hardly going to bother anyone. Many people put a lot of effort into making sure that men can come out clean from a variety of sex scandals. Shame and shame have not disappeared from society. It's just shameful to do other things now. It is becoming increasingly difficult to predict which ones.

Because the decision about what's shameful and what's not is made by the Twitter crowd. It's where we decide who hears the destruction and doesn't ask the legal system for advice. This fact makes us unpredictable and dangerous.

Psychiatrist James Gilligan spent his life studying how shame corrodes the inner world of prisoners. In the 1970s, there was an outbreak of violence in American prisons: suicides and murders in the walls of the colonies sharply increased. Gilligan was sent to study this phenomenon. In almost every conversation, the inmates told him they had long felt dead. Shame – aggravated by the disdainful attitude of the guards – ate them so much that they no longer had any emotions. And so they started cutting themselves or others. To see if they're capable of any more feelings.

In 1991, James Gilligan began collaborating with Harvard University, attracting professors to give free lectures in prisons. After all, what can help people regain their dignity, but education? At the same time there was a campaign of Governor William Weld. At a press conference, journalists asked him how he felt about Gilligan’s initiative. Oeld replied: “We should stop with this project — we should not give prisoners free higher education. Otherwise, those people who do not have enough money for it will commit crimes to attend university courses for free.” Needless to say, that's where Gilligan's educational program ended?

In the early 1990s, search engines sorted information only by the number of times the keywords were searched for on a given page. For example, if I scored my name on AltaVista or HotBot, the first line would pop up a page where my name would just be repeated a million times. (This would be my favorite site, but I think it would have a few other fans.)

And then two Stanford students -- Larry Page and Sergey Brin -- came up with a different concept. They decided it was time to make a new search engine that would rank websites by their popularity. If someone links to your page, you get points. After all, a reference is like a quote is a sign of respect. They named their new system PageRank after Larry Page.

Today, there are agencies that restore the “honor” of customers who were bullied on the Internet. They are creating new profiles for victims on Twitter, LinkedIn and Tumblr, because these sites have an innate high PageRank rating. The algorithm throws them up as the most popular. But the problem with Google is that the algorithm is constantly changing. It seems that preference is given to old sites or, conversely, new ones – and everything in the middle (over 12 weeks) is poorly indexed.

Most of all, clients of such agencies are afraid of reversion. For them, there is nothing scarier in the world than seeing links to good resources roll back to the second page, and the first resurfaces the old horror.

Once upon a time there was a saying on the Internet that as soon as you compare something to Nazism in an argument, you immediately lose the argument. Perhaps the same can be said about the Stasi, the secret police in the GDR.

The horror of the Stasi was not only that there was physical violence. The main goal of the Stasi was to create the largest network of guards over each other in the history of mankind. And perhaps this example can teach us something about modern digital society.

In 2003, 14 years after the destruction of the Stasi and three years before the invention of Twitter, Anna Funder wrote the book Stasiland.

Of course, no secret agent intercepted Justin Sacco's thoughts. She tweeted them herself, naively believing that Twitter is a safe place to tell strangers the truth about yourself. And this idealistic experiment ended pretty badly for her.

Funder was able to interview a former Stasi official whose job was to recruit new whistleblowers. Funder tried to ask him why people agreed to work for the Stasi, when they were so poorly paid for it, and there were so many jobs. Most people said yes simply because they wanted to feel important, because every week the Stasi listened to their stories about their neighbors.

I was struck by the condescension with which a former secret police officer spoke of his informants. Perhaps the same can be said about Twitter users. Social media gives voice to previously voiceless people - that's egalitarianism at its best. But the conclusion that psychologists came to when they studied the success of the Stasi recruiters was, “People went to work as informants because they just wanted to make sure their neighbors were doing the right thing.”

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: theoryandpractice.ru