225

Pushkin's jewelry

Maria Alexandrovna Gartung Pushkin, the eldest daughter of Pushkin, was born on the night of May 18-19, 1832. On June 7, the girl was baptized in the Sergievsky Cathedral of All Artillery. She received her name in honor of the late grandmother of Alexander Sergeyevich - Maria Alekseevna Hannibal.

In infancy, the girl was not in good health and was often ill. Pushkin was very concerned. “Does Mary speak?” Does he? What teeth? What is my toothless Puskin? he wrote to his wife, and immediately added: “These are my teeth!”

In a letter to Princess Vyazemskaya, the poet pretended to lament: “My wife had the awkwardness of allowing a small lithography from my person.”

558583.

Masha was the only one of the poet’s children who had at least vague memories of his father – when he died, she was in her fifth year, the brothers and sister Natasha were very young.

Pushkin's daughter Maria spent the early years of her childhood in the Polotny Plant, in the village volley - she was taken away from St. Petersburg when she was five years old. Natalia Nikolaevna wore mourning and therefore went to her family estate, away from the light and bustle.

Pushkin's eldest daughter She received a home education and at the age of 9 she was fluent in speaking, reading and writing French and German, playing music and playing chess. Upon returning to the capital (in 1839), Marie and her brothers were seriously engaged in several teachers recommended by friends of her father.

Marie made great progress in chess, drawing and needlework, learning foreign languages. The eldest daughter of the poet ardently loved Russian literature, had extraordinary abilities, played the piano well.

Everyone who met Maria Alexandrovna noted that she was very friendly and easy to handle, unusually beautiful. “The rare beauty of her mother mixed in her with the exoticism of her father, although her facial features may have been somewhat large for a woman,” he wrote.

Pushkin’s biographer Pyotr Ivanovich Bartenev wrote about Maria that “grown up, she took beauty from her beautiful mother, and from her resemblance to her father she retained that sincere heartfelt laughter, which was said to be as fascinating to Pushkin as his poems.”

In December 1852, after graduating from the Institute, Pushkin was granted the highest honors in the maid of honor and was under the Empress Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Emperor Alexander II.

Despite the increased attention to her from the cavaliers, Maria Alexandrovna married late, at twenty-eight years old. Her husband was Major General Leonid Hartung, who managed the imperial stud factories in Tula and Moscow.

After the death of his father in 1859, he inherited the estate in Tula province. Having taken possession, Leonid Nikolayevich was engaged in the redevelopment and reconstruction of the estate in the village of Fedyashevo: he smashed the estate park and made a dam with a pond on the Fedyashevka river - the pond around the estate in a picturesque semicircle, and his sleeve went into the park.

And now the two-storey house is striking in size: on the first floor there were rooms for servants and guests, Gartung’s office, a huge library and a fireplace, and on the second – 11 large halls! There is an opinion (however, not confirmed by documentation) that this two-storey house was built by Maria Alexandrovna herself.

Their ancestral nest, where musical evenings and “tea balls” were often held, becomes famous in the district. At one of the balls in 1861 with Maria Alexandrovna met Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy.

There is a lot of evidence that the writer gave his heroine Anna Karenina the peculiar features of Maria Pushkina, her original beauty. He himself admitted this: in the draft version of his Anna Karenina, the main character bore the name of Anastasia (Nana), and her surname was Pushkin.

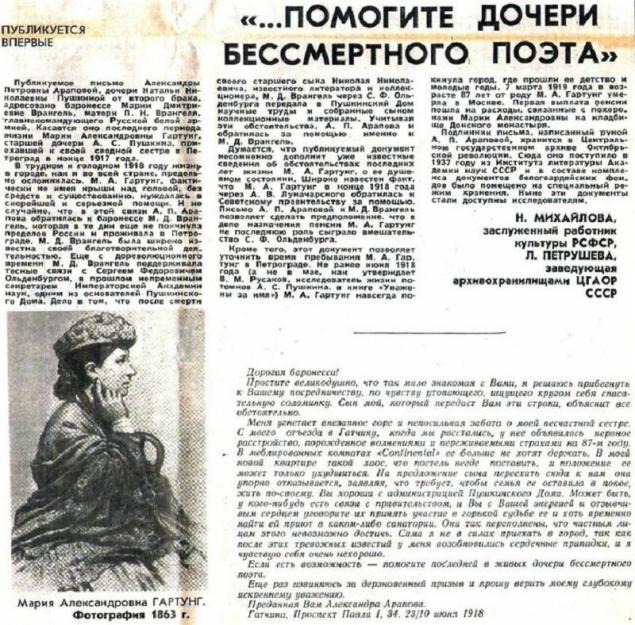

In the exposition of the State Museum of Leo Tolstoy in the section dedicated to the novel “Anna Karenina”, there is a portrait of M. A. Hartung, made by I. K. Makarov in 1860. It depicts Maria Alexandrovna with a pearl necklace inherited from her mother, and a garland of panty eyes in her hair.

But as Tolstoy describes Anna Karenina in the novel: On her head, in black hair, her own without admixture, there was a small garland of panty eyes and the same one on the black ribbon belt between white lace. Her hair was invisible. Were noticeable only, decorating it, these willful short rings of curly hair, always protruding on the back of the head and temples. On the sharpened strong neck was a string of pearls.”

Their marriage ended tragically after 17 years. In 1877, General Hartung was unjustly accused of stealing bills of exchange and other securities by a certain Zanftleben, an interest-bearer whose duties as executor were assumed by Hartung.

In an effort to avoid embarrassment, the general shot himself in the courthouse. Hartung wrote, “I swear by Almighty God that I have not stolen anything and forgive my enemies.” The jury found Gartung guilty, but he did not care.

Posthumously, Leonid Nikolayevich was fully acquitted, and his good name was restored. Her husband’s suicide was a terrible blow to Mary. She sold the estate and moved to Moscow. Maria Alexandrovna never married again.

Mary had no means of subsistence. She sent a request for help to Emperor Alexander II, and help was immediately provided. She was assigned a pension of 240 rubles a year and only by the centenary of her father the amount was rounded up to 300 rubles a year.

In 1899, to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s birth, a city library-reading room was created in Moscow, which was solemnly opened on May 2, 1900. Maria Alexandrovna was her guardian until 1910, when her age and ill health forced her to give up her job.

The Moscow City Library named after A. S. Pushkin is located on Elokhov Square, in an ancient manor of the XVIII century. Above the main staircase is a large portrait of M. A. Hartung.

Maria Alexandrovna, the only child of Pushkin, lived to see the October Revolution. The Soviet government condemned her to starvation, recalling her noble origin, her service as a maid of honor at the court of the Empress, and in general all the “noble merits”.

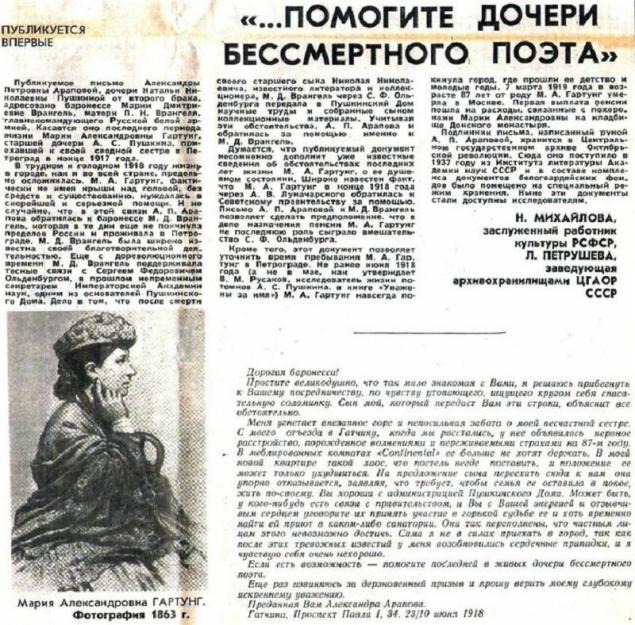

Her sister Anna Arapova (daughter of Natalia Nikolaevna from her second marriage to Lansky) appealed for help to her friend Baroness Wrangel with a request not to abandon the daughter of the great poet, the last surviving heiress of Pushkin. Baroness Wrangel, known for her charity, wrote a letter to Lunacharsky.

The People’s Commissar of Education sent to Maria Alexandrovna an employee of the People’s Commissariat of Information to find out “the degree of her need.” Lenin personally signed the pension document for Pushkin’s beloved daughter, but only a few days before the death of Maria Alexandrovna. She died of starvation in Moscow on February 22 (March 7), 1919.

The People’s Commissariat of Social Security, “taking into account the merits of the poet Pushkin before Russian fiction,” appointed a pension, but the first amount went to the funeral of Maria Alexandrovna. She never received her “Soviet” pension, and her modest house in Dog Lane was demolished when the New Arbat was being built. The grave of Pushkina is located in the cemetery of the Don monastery.

Shortly before her death, Maria Alexandrovna had a habit of sitting for a long time at the monument to Pushkin in Moscow. Some, seeing her, slowed down or turned around. They did not quite understand what a tall woman does, head to toe in black, wrapped in a veil, in any weather at the monument to Pushkin on Tversky Boulevard. The poet Nikolai Dorizo dedicated lines to her:

“She comes here every day.

And on Tverskoy Boulevard motionless.

Sitting in old age, and old years

They talk to her for a long time.

Memories of an old handkerchief

She's warmed by her bent shoulders.

She comes here all the time.

With a cloves of scarlet in a wrinkled hand,

Pushkin's daughter is Maria's favorite.

"How's Mashka?" he wrote about her in letters.

She'll put a flower on granite.

Then he'll sit quietly.

What took so long, so cherished

Is he talking to a great father?

In all of Russia, only she knows.

A lonely old lady,

How sweet and hot they were sometimes

These are Pushkin's bronze hands.

She's getting up. It's time to go to my apartment.

Leaving. Dissolving in the crowd

Slowly, silently, namelessly.

If you are interested in the difficult fates of our famous compatriots, pay attention to the article about Elena Petrovna Blavatsky, a mysterious and brilliant Russian woman who laid the foundations of the Theosophical movement.

“100 years is an unseemly lot, but I still want to live ...” – said the famous singer Isabella Yuryeva. She was a symbol of the era, charmed men with her beauty, and conquered millions of hearts with her voice. "Site" He will tell you about the fate of this beautiful woman.

In infancy, the girl was not in good health and was often ill. Pushkin was very concerned. “Does Mary speak?” Does he? What teeth? What is my toothless Puskin? he wrote to his wife, and immediately added: “These are my teeth!”

In a letter to Princess Vyazemskaya, the poet pretended to lament: “My wife had the awkwardness of allowing a small lithography from my person.”

558583.

Masha was the only one of the poet’s children who had at least vague memories of his father – when he died, she was in her fifth year, the brothers and sister Natasha were very young.

Pushkin's daughter Maria spent the early years of her childhood in the Polotny Plant, in the village volley - she was taken away from St. Petersburg when she was five years old. Natalia Nikolaevna wore mourning and therefore went to her family estate, away from the light and bustle.

Pushkin's eldest daughter She received a home education and at the age of 9 she was fluent in speaking, reading and writing French and German, playing music and playing chess. Upon returning to the capital (in 1839), Marie and her brothers were seriously engaged in several teachers recommended by friends of her father.

Marie made great progress in chess, drawing and needlework, learning foreign languages. The eldest daughter of the poet ardently loved Russian literature, had extraordinary abilities, played the piano well.

Everyone who met Maria Alexandrovna noted that she was very friendly and easy to handle, unusually beautiful. “The rare beauty of her mother mixed in her with the exoticism of her father, although her facial features may have been somewhat large for a woman,” he wrote.

Pushkin’s biographer Pyotr Ivanovich Bartenev wrote about Maria that “grown up, she took beauty from her beautiful mother, and from her resemblance to her father she retained that sincere heartfelt laughter, which was said to be as fascinating to Pushkin as his poems.”

In December 1852, after graduating from the Institute, Pushkin was granted the highest honors in the maid of honor and was under the Empress Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Emperor Alexander II.

Despite the increased attention to her from the cavaliers, Maria Alexandrovna married late, at twenty-eight years old. Her husband was Major General Leonid Hartung, who managed the imperial stud factories in Tula and Moscow.

After the death of his father in 1859, he inherited the estate in Tula province. Having taken possession, Leonid Nikolayevich was engaged in the redevelopment and reconstruction of the estate in the village of Fedyashevo: he smashed the estate park and made a dam with a pond on the Fedyashevka river - the pond around the estate in a picturesque semicircle, and his sleeve went into the park.

And now the two-storey house is striking in size: on the first floor there were rooms for servants and guests, Gartung’s office, a huge library and a fireplace, and on the second – 11 large halls! There is an opinion (however, not confirmed by documentation) that this two-storey house was built by Maria Alexandrovna herself.

Their ancestral nest, where musical evenings and “tea balls” were often held, becomes famous in the district. At one of the balls in 1861 with Maria Alexandrovna met Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy.

There is a lot of evidence that the writer gave his heroine Anna Karenina the peculiar features of Maria Pushkina, her original beauty. He himself admitted this: in the draft version of his Anna Karenina, the main character bore the name of Anastasia (Nana), and her surname was Pushkin.

In the exposition of the State Museum of Leo Tolstoy in the section dedicated to the novel “Anna Karenina”, there is a portrait of M. A. Hartung, made by I. K. Makarov in 1860. It depicts Maria Alexandrovna with a pearl necklace inherited from her mother, and a garland of panty eyes in her hair.

But as Tolstoy describes Anna Karenina in the novel: On her head, in black hair, her own without admixture, there was a small garland of panty eyes and the same one on the black ribbon belt between white lace. Her hair was invisible. Were noticeable only, decorating it, these willful short rings of curly hair, always protruding on the back of the head and temples. On the sharpened strong neck was a string of pearls.”

Their marriage ended tragically after 17 years. In 1877, General Hartung was unjustly accused of stealing bills of exchange and other securities by a certain Zanftleben, an interest-bearer whose duties as executor were assumed by Hartung.

In an effort to avoid embarrassment, the general shot himself in the courthouse. Hartung wrote, “I swear by Almighty God that I have not stolen anything and forgive my enemies.” The jury found Gartung guilty, but he did not care.

Posthumously, Leonid Nikolayevich was fully acquitted, and his good name was restored. Her husband’s suicide was a terrible blow to Mary. She sold the estate and moved to Moscow. Maria Alexandrovna never married again.

Mary had no means of subsistence. She sent a request for help to Emperor Alexander II, and help was immediately provided. She was assigned a pension of 240 rubles a year and only by the centenary of her father the amount was rounded up to 300 rubles a year.

In 1899, to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s birth, a city library-reading room was created in Moscow, which was solemnly opened on May 2, 1900. Maria Alexandrovna was her guardian until 1910, when her age and ill health forced her to give up her job.

The Moscow City Library named after A. S. Pushkin is located on Elokhov Square, in an ancient manor of the XVIII century. Above the main staircase is a large portrait of M. A. Hartung.

Maria Alexandrovna, the only child of Pushkin, lived to see the October Revolution. The Soviet government condemned her to starvation, recalling her noble origin, her service as a maid of honor at the court of the Empress, and in general all the “noble merits”.

Her sister Anna Arapova (daughter of Natalia Nikolaevna from her second marriage to Lansky) appealed for help to her friend Baroness Wrangel with a request not to abandon the daughter of the great poet, the last surviving heiress of Pushkin. Baroness Wrangel, known for her charity, wrote a letter to Lunacharsky.

The People’s Commissar of Education sent to Maria Alexandrovna an employee of the People’s Commissariat of Information to find out “the degree of her need.” Lenin personally signed the pension document for Pushkin’s beloved daughter, but only a few days before the death of Maria Alexandrovna. She died of starvation in Moscow on February 22 (March 7), 1919.

The People’s Commissariat of Social Security, “taking into account the merits of the poet Pushkin before Russian fiction,” appointed a pension, but the first amount went to the funeral of Maria Alexandrovna. She never received her “Soviet” pension, and her modest house in Dog Lane was demolished when the New Arbat was being built. The grave of Pushkina is located in the cemetery of the Don monastery.

Shortly before her death, Maria Alexandrovna had a habit of sitting for a long time at the monument to Pushkin in Moscow. Some, seeing her, slowed down or turned around. They did not quite understand what a tall woman does, head to toe in black, wrapped in a veil, in any weather at the monument to Pushkin on Tversky Boulevard. The poet Nikolai Dorizo dedicated lines to her:

“She comes here every day.

And on Tverskoy Boulevard motionless.

Sitting in old age, and old years

They talk to her for a long time.

Memories of an old handkerchief

She's warmed by her bent shoulders.

She comes here all the time.

With a cloves of scarlet in a wrinkled hand,

Pushkin's daughter is Maria's favorite.

"How's Mashka?" he wrote about her in letters.

She'll put a flower on granite.

Then he'll sit quietly.

What took so long, so cherished

Is he talking to a great father?

In all of Russia, only she knows.

A lonely old lady,

How sweet and hot they were sometimes

These are Pushkin's bronze hands.

She's getting up. It's time to go to my apartment.

Leaving. Dissolving in the crowd

Slowly, silently, namelessly.

If you are interested in the difficult fates of our famous compatriots, pay attention to the article about Elena Petrovna Blavatsky, a mysterious and brilliant Russian woman who laid the foundations of the Theosophical movement.

“100 years is an unseemly lot, but I still want to live ...” – said the famous singer Isabella Yuryeva. She was a symbol of the era, charmed men with her beauty, and conquered millions of hearts with her voice. "Site" He will tell you about the fate of this beautiful woman.

Nyudomania: 10 ideas of stylish manicure in calm tones Not just beige and pink!

Cheat sheet for caring moms! Remember, keep it.