545

Shocking photo — collectors of the village of coal Bokapahari, India

In Bokapahari, India, thousands of people live in the thick of a near coal mines. They earn about $2 a day selling coal, stolen from the state mines.

The government has spent millions to build new apartments for them, but residents are still here.

1.The miners return home after a long day of work in coal mines in the village of Bokapahari, India. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

2.Coal fire is raging just below the surface of the earth, making it too hot to walk barefoot. From crack release harmful gases in and around the home. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal).

3.The children dug the coal from the mine. The Central government has spent $ 5 million to build 2400 new apartments in the house for the residents of Bokapahari. But residents say that they can't earn a living if they get 8 miles to live in a new complex. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

4.Moreover, residents complain that the new apartments with 11-foot rooms, with bathroom and kitchen, too small for families, which often consist of 6-10 people. Photo residents dig coal from the mines. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

5.The government has set a priority on the recovery of rural areas in India. Billions of dollars are being invested in economic development and work to improve the grim living conditions of hundreds of millions of citizens. But many of the government's ambitious plans to assist the most vulnerable segments of the population fail because they were not well thought out and executed. The photo on the right Jalo Bhuia, who works in the mines of Jharia. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

6.The residents returned with baskets of coal back to their village. The representatives of "Bharat Coking Coal" claim that the labour is a violation and endangers their lives. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

7.Collectors of coal in Bokapahari say that the real reason for relocation — the government wants to move them to the poorer mine. In the photo people say about the problems with dust and pollution in Kujama Basti, a village a few miles from Bokapahari. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

8.Government officials insist that safety is their first goal, although they recognize that to fulfill the plan on mining a million tons of coal in Bokapahari.(Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

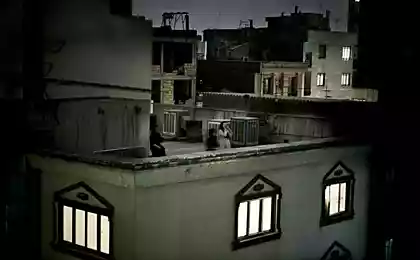

9.People gathered to share work over the last few days. Jharia and the nearest village Bokapahari lie in the coal basin in the form of a turtle, covering an area of 450 sq km It is one of the largest coal reserves of India.(Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

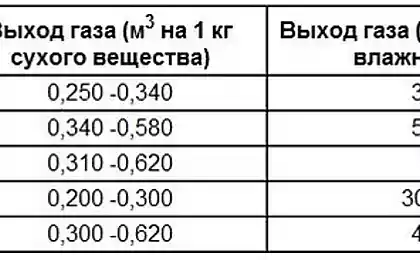

10.Today, more than 70% of the electricity thanks to coal India gets fuel. The government is trying to increase coal production to rid of the acute shortage of energy in the factories and in their growing cities. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

11.The Indian government has started the resettlement of rural inhabitants from the danger zone after a series of disasters in which people, houses and sections of the road neojidanno disappeared under the ground. In 1996, several houses in the area collapsed within two hours. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

12.By 1999, local and national government officials had developed a plan for moving people, roads and train lines under threat of extinction as a result of fires. In the photo a villager sits on the corner.Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

13.Nothing happened until 2007. when construction began on the first residential complex for rural residents. 2400 apartments were ready a year ago in the first of the five villages planned for resettlement. Last year the Federal government appropriated about $ 2 billion to move 97000 families who live on the edge of the burning mines. Railway lines and roads should be shifted and the fires in the area extinguished once and for all. Govinda Bhuia, left and Arbeen Bhuia, right to work in the mines of Jharia. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

14.Ajay Singh, Director On the development and rehabilitation of Jharia, head of the resettlement plan, said that pereselenie villages — the hardest job with which he was faced during his 15-year career employee of the Indian administration. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

источник:photo-finish.ru

Source: /users/1077

The government has spent millions to build new apartments for them, but residents are still here.

1.The miners return home after a long day of work in coal mines in the village of Bokapahari, India. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

2.Coal fire is raging just below the surface of the earth, making it too hot to walk barefoot. From crack release harmful gases in and around the home. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal).

3.The children dug the coal from the mine. The Central government has spent $ 5 million to build 2400 new apartments in the house for the residents of Bokapahari. But residents say that they can't earn a living if they get 8 miles to live in a new complex. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

4.Moreover, residents complain that the new apartments with 11-foot rooms, with bathroom and kitchen, too small for families, which often consist of 6-10 people. Photo residents dig coal from the mines. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

5.The government has set a priority on the recovery of rural areas in India. Billions of dollars are being invested in economic development and work to improve the grim living conditions of hundreds of millions of citizens. But many of the government's ambitious plans to assist the most vulnerable segments of the population fail because they were not well thought out and executed. The photo on the right Jalo Bhuia, who works in the mines of Jharia. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

6.The residents returned with baskets of coal back to their village. The representatives of "Bharat Coking Coal" claim that the labour is a violation and endangers their lives. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

7.Collectors of coal in Bokapahari say that the real reason for relocation — the government wants to move them to the poorer mine. In the photo people say about the problems with dust and pollution in Kujama Basti, a village a few miles from Bokapahari. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

8.Government officials insist that safety is their first goal, although they recognize that to fulfill the plan on mining a million tons of coal in Bokapahari.(Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

9.People gathered to share work over the last few days. Jharia and the nearest village Bokapahari lie in the coal basin in the form of a turtle, covering an area of 450 sq km It is one of the largest coal reserves of India.(Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

10.Today, more than 70% of the electricity thanks to coal India gets fuel. The government is trying to increase coal production to rid of the acute shortage of energy in the factories and in their growing cities. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

11.The Indian government has started the resettlement of rural inhabitants from the danger zone after a series of disasters in which people, houses and sections of the road neojidanno disappeared under the ground. In 1996, several houses in the area collapsed within two hours. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

12.By 1999, local and national government officials had developed a plan for moving people, roads and train lines under threat of extinction as a result of fires. In the photo a villager sits on the corner.Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

13.Nothing happened until 2007. when construction began on the first residential complex for rural residents. 2400 apartments were ready a year ago in the first of the five villages planned for resettlement. Last year the Federal government appropriated about $ 2 billion to move 97000 families who live on the edge of the burning mines. Railway lines and roads should be shifted and the fires in the area extinguished once and for all. Govinda Bhuia, left and Arbeen Bhuia, right to work in the mines of Jharia. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

14.Ajay Singh, Director On the development and rehabilitation of Jharia, head of the resettlement plan, said that pereselenie villages — the hardest job with which he was faced during his 15-year career employee of the Indian administration. (Sanjit Das/Panos for The Wall Street Journal)

источник:photo-finish.ru

Source: /users/1077

The stone in the interior — decor ideas

Teach your children to Be Happy in life — a few simple truths