468

How functional our DNA

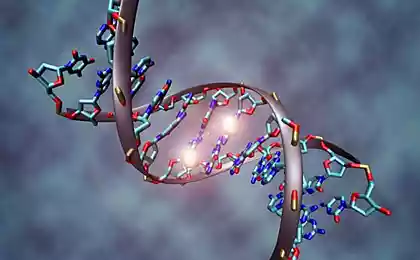

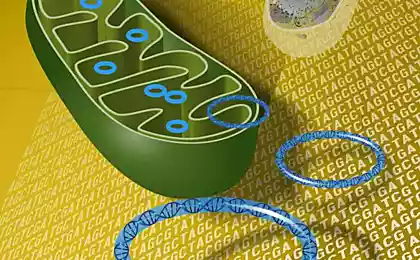

The human genome consists of six billion DNA segments. But how many of them actually doing something important? Two years ago, the ENCODE scientists came to the conclusion that a large part of the DNA, 80%, functioning as expected. Since then, everything has changed.

Initial assessment immediately picked up by the media and attracted public attention, genetics called the results "absurd". The latest study conducted by Dr. Gerton Lunteren from Oxford University, showed that only 8.2% of human DNA is functional.

The transition from 80 to 8.2 percent seems extreme and you might wonder how two studies could come to such different results? Scientist at the University of Melbourne Charles Robin explains that the difference lies in the definition of the term "functional".

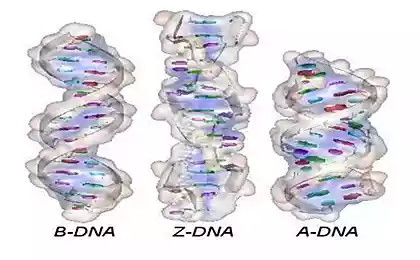

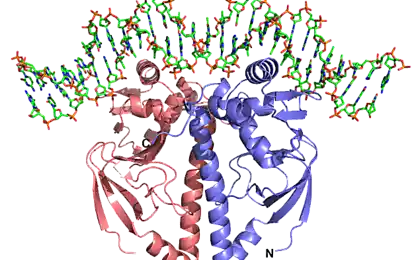

ENCODE identified the functionality as "biochemical function" — that is, if a segment of DNA associated with specific proteins, it will be "biochemically functional", even if has no effect on the phenotype of the individual.

Of course, this vision functionality has led to the fact that 80% of DNA is "functional". Nevertheless, many scientists do not agree with this definition.

Dr. Robin suggested the term "functionality" to refer to DNA segments, which, when damaged, can lead to harmful effects; thus, these stretches of DNA will be crucial for development. The same definition was used by Lunter and his colleagues in a recent study.

To test this, genetics can deliberately remove segments of DNA and to study the implications. However, there are obvious ethical limitations to test this on humans. Instead, the research team studied Lunter violations generated by evolution, to assess which stretches of DNA are functional. In fact, those sequences that have remained unchanged or well-preserved, likely functional, whereas the areas without features are constantly evolving over time, without any restrictions.

Scientists have studied a number of species with different level of genetic differences from humans. The functional part of the genome has changed during evolution together with the evolution of species, which led to a phenotypic revolution, which, in turn, led to the fact that man does not look like a mouse, for example. Lunter and his colleagues calculated the differences between the human genome and the genomes of species at different stages of evolution and came to the assessment at 8.2%.

"This figure was 8.2% — not surprising, says Robin. — This was to be expected based on previous studies. The great thing about this work, however, is quantitative methods, which give us a clear answer."

The results will not only have serious consequences for research in the field of genetics, but will also be important for other areas such as medical research. Using a mouse model, and knowing the differences in functional genes between mice and humans, scientists can better understand why people react not like mouse during medical tests.

The next step for scientists will be to determine the functions of these important 8.2% of DNA. As for the remaining 91.8% of the DNA, but it seems mostly useless. Although among this set of segments can be coded interesting elements of the work of DNA in General.

Source: hi-news.ru

Unique moments caught in a frame

It is important to know the cases of contra— indications of medicinal herbs