448

The success story of Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX and a fantastic future

In late October 2001, Elon Musk arrived in Moscow to buy an intercontinental ballistic missile. He arrived with Jim Cantrell, a sort of international space technician, and Adeo Ressi, his best friend from Pennsylvania. Although Musk had tens of millions in the bank, he tried to get a cheaper rocket. They planned to buy a decommissioned missile, not a new one. Musk thought it would be a great vehicle to send a plant or a few mice to Mars.

Ressi, a lanky eccentric, had long believed that his best friend was crazy or slightly moved, and put sticks in the wheels of the project. He bombarded Musk with references to videos of Russian, European and American rocket explosions. He was constantly bringing Musk’s friends together to talk him out of wasting money. But it didn't work. Musk confidently continued to finance the grand space spectacle and put a lot of effort into it. So Ressie had to go with Musk to Russia to follow Musk with good intentions.

Adeo took me aside and said, Elon is doing something crazy. A philanthropic gesture? It's crazy, Cantrell says. - He was seriously concerned.

The group agreed to meet with several companies such as Lavochkin’s NGO, which made Mars and Venus probes for the Russian Federal Space Agency, and Kosmotras, a commercial rocket launch organization with an office in Moscow. All meetings were held almost the same, in the best Russian traditions. Russian representatives of space companies, often skipping breakfast, like to schedule a meeting at 11 a.m. in the office with a small breakfast, eyewitnesses recall. Then there's a little chat for an hour or more while visitors are treated to sandwiches, sausages and, of course, vodka (let's not forget - it was 2001). After lunch there was a smoke break and coffee. And after all the tables had been cleared, a company representative would turn to Musk and ask, "So what purchase are you interested in?" The nervous tension would be less if the Russians took Musk more seriously. But they saw him as a newcomer who had just arrived in space and didn't take his bravado.

“One of their chief designers didn’t care about Elon and me because he thought we were stupid,” Cantrell said. Musk's team returned empty-handed.

In February 2002, the group returned to Russia, capturing Mike Griffin, who had worked at the CIA’s In-Q-Tel Venture Division and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and had just left Orbital Sciences, a satellite and spacecraft manufacturer. Now Musk wanted to take not one but three missiles and armed himself with a suitcase full of money. They met with representatives of Kosmotras in a beautiful and rich pre-revolutionary building in the suburbs of Moscow. The vodka toasts began with “For Space!” and “For America!”, and after a little wave, Musk asked directly how much the rocket would cost. Eight million dollars each, they said. Musk offered eight million for two. "They sat down and looked at him," Cantrell says, "and said something like "Boy." Nope. They also hinted that he had no money.” At this point, Musk decided that the Russians were either not serious about business negotiations, or wanted to squeeze the millionaire’s money to the maximum. He interrupted the meeting.

Overseas negotiators got out in the snow and blizzard of Moscow winter, caught a taxi and headed straight to the airport. The Russian missiles were the only ones that fit Musk’s budget, but they were too hard to work with. "The road was long," Cantrell recalls. We sat in silence watching Russian snowflakes fall into the snow. A gloomy mood persisted all the way to the plane until a cart of drinks pulled up. "The mood is always up when you take off from Moscow," Cantrell says. It’s like, ‘Oh my God, I did it.’ So Griffin and I took a drink and went nuts.” Musk sat in a row across from him and typed something on his computer. “We thought, ‘Here’s a jackass, what can he do now?’” At this point, Musk turned around and showed the table he had created.

"Hey, guys," he said, "I think we can build this rocket ourselves."

Just a few months ago, in June 2001, Musk turned thirty. "I'm not a child prodigy boy anymore," he told his wife and college sweetheart, Justine, either seriously or jokingly. Musk emigrated from South Africa in 1988 and made millions at two companies, Zip2 and PayPal. Now he was expected to act as a typical rich dotcom major and brew another web service. But Musk wanted more. As a child, he dreamed of spaceships and travel, greedily devouring Heinlein, Asimov and Douglas Adams. Most people would have had a triumph in Silicon Valley. But for Musk, it was just a stepping stone.

The change in his attitude and thinking was evident to friends, including a group of PayPal executives who gathered in Las Vegas one weekend to celebrate the recent sale. “We were hanging out at some Hard Rock Cafe house while Elon was reading some murky Soviet-era rocket science textbook, all shabby and seemingly bought on eBay,” said Kevin Hartz, one of PayPal’s early investors. He studied it and spoke openly about space travel and how the world would change.

Elon and Justine decided to move south to start a family and start a new chapter of their lives in Los Angeles. Unlike many seedlings from Southern California, they were made of technology. The mild, fitting weather made it ideal for the aviation industry, which had been there since the 1920s when Lockheed Martin opened a store in Hollywood. It was followed by Howard Hughes, the US Air Force, NASA, Boeing and others. Although Musk’s space plans were vague at the time, he was confident that he would find the right people for the space industry and persuade them to join his new venture.

Musk began with the collapse of the Mars Society, a unique collection of space enthusiasts who gathered to explore and explore the Red Planet. Each member of the society was raised 500 bucks to gather in the house of one of the honorary members of the Mars Society. What surprised Robert Zubrin, the head of the group, was the response of someone named Elon Musk, who was not invited by any member of the society.

“He gave us a check for $5,000,” Zubrin said. - Everyone paid attention to it.

Zubrin invited Musk for coffee before lunch and told him about a research center that the society had built in the Arctic to replicate the conditions of Mars, and about an experiment called the Translife Mission, during which a team of mice were to go into orbit. Mice had to give birth to babies under a gravity of one-third the size of Earth’s — like on Mars.

When it came time for lunch, Zubrin seated Musk in a place of honor next to himself, directed by James Cameron and Carol Stoker, a NASA planetary scientist. Musk was thrilled.

“He was much more active than other millionaires,” recalls Zubrin. He didn’t know much about space, but he had a scientific mindset. He wanted to know exactly what was planned for Mars and what the consequences might be.” Almost immediately, Musk joined the Mars Society and took a seat on the board. He donated an extra $100,000 to fund a research station in the desert.

Musk's friends at the time were not fully confident in Musk's mental health. He contracted malaria while on holiday in Africa and lost a lot of weight in the fight against it. Musk is only 185 centimeters tall, but he usually seems taller. He's broad-shouldered, tight-knit, stocky. True, the new version of the Mask, although slightly exhausted, but planned to do something important in his life.

“He said, logically, you have to move forward in the direction of the sun, but I have no idea how to make money from it,” said George Zachary, an investor and close friend of Musk. He started talking about space, and I thought he was talking about real offices and homes. In fact, Musk began to think about plans far beyond the plans of the Mars Society. Instead of sending mice into Earth orbit, Musk decided to send them to Mars.

"He asked if I thought it was crazy?" says Zachary. And I asked if the mice would come back. Because if they don't, most people will think it's crazy. Musk said that the mice will not only visit Mars, but will also return and bring offspring.

Musk built a network of space experts and gathered the best of them in a series of salons - sometimes at the Renaissance Hotel at Los Angeles Airport, sometimes at Sheratin in Palo Alto. Musk had no formal business plan. He mostly wanted to help them develop the idea of sending mice to Mars, or at least come up with something comparable. Musk hoped to demonstrate a beautiful gesture to humanity – to do something that would catch the world’s attention, make people think about Mars again, and reflect on human potential. There were also scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Cameron was, was Griffin. No one on the planet knew more about how to launch something into space than Griffin, and he advised Musk. He will be working with NASA in four years.

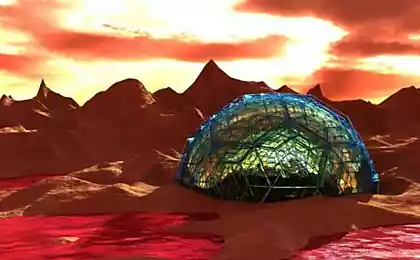

Experts were thrilled to have another rich guy who wants to fund something interesting in space. They were happy to discuss the possibilities and benefits of sending mice upstairs. But the conversation turned to another project, the Oasis of Mars. According to this scenario, Musk would buy a rocket and launch a robotic greenhouse on Mars, a plant-growing chamber that would open and take root in Martian regolith, or soil, and then set off in a lush color to produce Mars’ first oxygen. Much to Musk’s delight, the plan seemed feasible and promising.

Musk wanted the space greenhouse to be able to send videos back to Earth so people could watch the plants grow. The group also discussed the possibility of collecting kits from students across the country who want to grow their own plants and figure out, for example, that a Martian flower will grow twice as tall as its terrestrial relative over the same time period. Musk’s enthusiasm began to inspire a group of experts, many of whom were cynical about something new about space. There were engineering problems that needed to be solved. Taking Martian soil into a greenhouse looked not only physically challenging, but also problematic, as the soil could be toxic. For a while, scientists have discussed growing a plant in a nutrient gel, but it already looked like a hoax. Even optimistic moments are stuck in the unknown. One scientist found several tenacious mustard seeds and decided that they could survive the features of the Martian field.

"It wouldn't be nice if the plant died," says Dave Bearden, a space industry veteran who attended the meeting. Then you will have a dead garden on Mars.

Most of the space experts worried about the budget Musk. After the salons, it seemed that Musk was willing to spend 20-30 million dollars on all this, and everyone knew that just launching a rocket would eat all the money. But Musk had his own plans. He studied books he borrowed from Cantrell and others. There were "Elements of Rocket Propulsion", "Fundamentals of Astrodynamics", "Aerothermodynamics of Gas Turbine" and "Rocket Propulsion". According to Musk’s calculations, he could reduce the cost of an affordable rocket launch by building a small racket that can deliver small satellites and payload into space. Space Exploration Techologies, or SpaceX, was founded in June 2002. The beginning of the journey to Mars was laid.

SpaceX’s first headquarters is located in the old 1310 East Grand Avenue warehouse in El Segundo, a suburb of Los Angeles. There were 75,000 square meters of open space and several porches that allowed Musk to drive his silver McLaren F1 straight to the office. It was a hangar-like building with dusty floors and curved ceilings. Musk approached one of the cargo docks, raised the gate and unloaded the equipment on his own. Tables were scattered throughout the factory, so computer scientists and engineers designing machines could sit next to welders and locksmiths bringing these machines to life. For the aerospace industry, this was a bold decision. Ordinary aerospace companies separate engineers and machinists by thousands of kilometers.

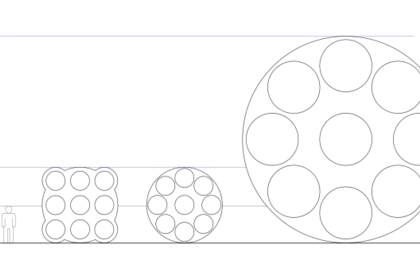

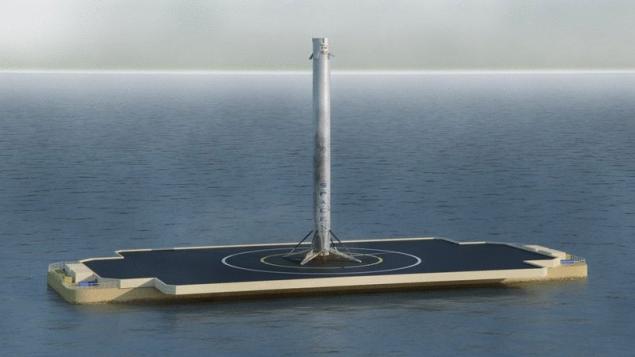

SpaceX planned to do things differently. Instead of assembling parts by thousands of suppliers, a company should build as many machines as possible. This includes both a mobile launch pad and rocket engines, which is incredible. Wherever possible, SpaceX should be faster, cheaper and better than its competitors. It was supposed to launch a lot of rockets every month, receive money every month, and not depend on government money or major suppliers. SpaceX's first rocket was called the Falcon 1, after the "Millennial Falcon" from Star Wars. And at a time when launching 250 kilograms of payload into orbit cost $30 million, Musk promised that the Falcon 1 would be able to lift 750 kilograms for $6.9 million.

The proposed timetable for the aerospace industry’s upheaval was ridiculously short. One of SpaceX's first presentations promised the first completed engine by May 2003, a second engine by June, a rocket hull by July and a full assembly by August. The launch pad was supposed to be ready by September, and the first launch of the rocket will take place, they say, in November 2003, 15 months after the creation of the company. The trip to Mars was supposed to take place in ten years. "Elon has always been an optimist," says Kevin Brogan, an early SpaceX employee. That is the best word to describe him. He can lie about when everything should be ready. He will choose the most aggressive term possible, confident that everything will go according to plan, and then fit everyone, believing that everyone should work even faster.”

Musk looked for young and active people, personally called the best students of aerospace institutes and hired them on the phone. "I thought it was a phone divorce," says Michael Colonno, whom Musk contacted while a Stanford student. I didn’t believe for a minute that he had a rocket company. But when students searched for Musk’s name online, hiring them at SpaceX became incredibly easy. After hearing about SpaceX’s ambitions, top engineers from Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Orbital Sciences also flowed into the upstart company.

For the first year at SpaceX, one or two new employees joined each week. Brogan became employee number 23 and came from TRW, an aerospace company that failed to form, where he was hampered by various internal policies, preventing him from working. “I called it a country club. Nobody did anything.” Brogan started working for SpaceX a day after the interview. He was told to stagger around the office and find a computer. "Then I had to go to Fry's store, get everything I needed, and then to Staples for a chair."

One of the first projects was the construction of a gas generator, such a small rocket engine that produces hot gas to power pumps. Tom Mueller, another TRW veteran, Tim Buzza, a defector from Boeing, and several other young engineers assembled a generator in Los Angeles, then packed it in a pickup truck and drove it to Mojave for testing. The Mojave Desert was 100 kilometers from Los Angeles and later became the center of aerospace companies like Scaled Composites and XCOR.

The SpaceX team borrowed the test bench from XCOR, its dimensions were ideal for a gas generator. The first launch took place at 11am and lasted 90 seconds. The generator worked, but released a black cloud that settled directly above the airport tower. In the days that followed, SpaceX engineers perfected a procedure that allowed them to run many tests a day - an unheard-of practice at the airport - and got the right gas generator after a couple of weeks of work.

The SpaceX team made several trips to Mojave and other locations, including a testbed at Edwards Air Force Base in Southern California and another in Mississippi. During this tour, SpaceX engineers visited a 300-acre test site in McGregor, Texas. It's left over from fellow billionaire Andrew Beal, who winded down his aerospace startup after pouring millions into a massive test site. SpaceX engineers fell in love with the place - and a three-story concrete stand - and persuaded Musk to buy it.

Jeremy Hallman, a young engineer, soon found himself living in Texas. Hallman embodies an example of the recruits Musk needed: he earned an aerospace engineer degree from the University of Iowa and a master’s degree in astronautics from the University of Southern California. He spent several years as a test engineer at Boeing, working with engines, rockets and spacecraft. At 23, Hallman was young, single and ready to devote any part of his life to working for SpaceX. He was second on Mueller's team.

Müller developed several three-dimensional computer models of the two engines he wanted to build. The Merlin was to be the Falcon 1 first-stage engine to tear the rocket off the ground, and the Kestrel was to be the small second-stage engine to drive it in space. Together, Hallman and Mueller have determined which parts SpaceX will build at the Los Angeles factory and which will try to buy. In the case of purchase parts, Hallman had to go to different machine shops and clarify the timing and delivery plans of the equipment. Quite often, sellers have told Hallman that SpaceX's timeline is pretty tight. Others were more agile and tried to adapt existing products to SpaceX’s needs, rather than building something from scratch. Hallman also found that ingenuity did a good job. He found, in particular, that if you replace several seals on the valves of car washers, they can be used with rocket fuel.

In addition to building its own engines, fuselages and capsules, SpaceX has developed its own motherboards and chips, vibration detection sensors, flight computers and solar panels. In the case of radio, SpaceX engineers have found that they can reduce the weight of the device by 20%. The overall savings were incredible, with the price of industrial-grade equipment used by aerospace companies dropping from $50,000 to $100,000 to $5,000 per SpaceX unit.

Even while working on Falcon 1, Musk planned to build something big, a Big Falcon Rocket. It would have the largest rocket engine in history. Musk’s focus on “bigger and faster” has amused and surprised some SpaceX suppliers, who have occasionally helped the company, such as Barber-Nichols, a Colorado manufacturer of turbopumps for rocket engines and other aerospace equipment. Bob Linden, an employee at Barber-Nichols, recalls those days.

"Elon showed up with Tom Mueller and started telling us that he was meant to launch things into space at a low cost and help us become spacefaring humans," he says. We weren't sure if Elon should be taken seriously. They started asking for the impossible. They needed a turbo pump that could be built in less than a year for less than $1 million. Boeing typically does such projects for five years and $100 million. Tom asked us to do our best, and we built it in 13 months. He was relentless.

After SpaceX built its first engine in a factory in California, Hallman loaded it with other equipment in a U-Haul trailer, hooked it to a white Hummer. H2 and drove from Los Angeles to the test site in Texas. Among the rattlesnakes, ants, insulation and incinerating heat, a group of engineers delivered the prototype engine to its place, filled it with liquid oxygen and kerosene, hid in a bunker behind an earthshaft and warmed it up for 0.1 seconds. The bad news was that it was a hell of a job. The good news was that nothing exploded. (This will happen later, and engineers will have a term for this case: Rapid unscheduled disassembly, RUD, rapid unplanned disassembly.) After the first successful burn, employees consecrated the site by drinking a $1,200 bottle of Remi Martin left over from a SpaceX initiation party from paper cups.

Over the next few years, the road from California to the test site will become known as the Texas Cattle Haul (literally the Texas Cattle Way). Engineers had to work 10 consecutive days in Texas, return to California for the weekend and then back. To ease the burden of travel, Musk sometimes allowed him to take his private jet. “It accommodated six,” Mueller says. “Seven, if someone sits in the toilet, it happens all the time.”

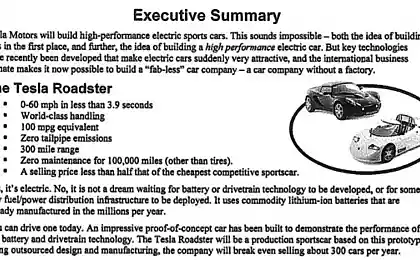

Tesla Motors Musk, of course, wasn’t just building rockets. In 2003, a year after he launched SpaceX, Musk co-founded Tesla Motors, which planned to sell sports electric cars. Musk has long dreamed of a good electric car, and although he has already invested $100 million in SpaceX, he has had to invest another $70 million in Tesla and become the company’s CEO. This decision almost ruined both companies.

While preparing for the filming of Iron Man in early 2007, director John Favreau rented a Los Angeles complex that was once owned by Hughes Aircraft, an aerospace and defense contractor founded 80 years ago by Howard Hughes. This facility had a series of interconnected hangars and served as the production base for the film. He also provided Robert Downey Jr., who played the role of Tony Stark, the creator of Iron Man, with plenty of inspiration. Downey looked with nostalgia at one of the large hangars, brought to an emergency condition. Not long ago, this building served as home to big ideas from a big man who shook the industry and wilfully did his thing.

Downey has heard of a man like Howard Hughes who will build his own industrial complex fifteen kilometers from the filming site of Iron Man. Instead of imagining what Hughes' life might have been like, Downey was given the opportunity to plunge into a more realistic environment. In March 2007, he visited SpaceX’s El Segundo headquarters and received an individual tour from Musk. "It's not easy to surprise me, but this place and this guy were amazing," Downey said.

In Downey’s eyes, the SpaceX factory looked like a giant, exotic hardware store. Everywhere there were enthusiastic employees working with an assortment of cars. Young white-collar engineers worked with blue-collar assembly line workers, and all seemed to share a genuine fascination with what they were doing. “The company was like an active startup,” Downey said. After the initial tour, Downey left, pleased with SpaceX's resemblance to Hughes' former factory.

The men took a walk, sat down in Musk's office and had lunch. Downey noted that Musk was not a foul-smelling, fussy and busy coder. Downey felt that Musk was one of those eccentric directors who could work with people in the factory. When Downey returned to the office where he was working on the film, he asked Favreau to place a Tesla Roadster in Tony Stark's studio. "After meeting Elon and his performance for me, I decided I would need his presence in the workshop," Downey says. - They became contemporaries. Elon was one of the people Tony used to hang out and have fun with, or even suddenly go into the wild jungle to drink potions with shamans. Musk later made a cameo appearance in Iron Man 2.

Musk has enjoyed his promotion. Together with Justine, they bought a house in Bel Air. Their neighbors were Quincy Jones and Joy Francis, creator of the Girls Gone Wild video. Musk and several former PayPal employees produced "Thank You for Smoking" and used Musk's plane in the film. Not being a coutile, Musk was involved in Hollywood nightlife and his social scene. "We had a household staff of five; by day the house turned into a workplace," Justine wrote in an article for Marie Claire. We entered the black tie club and got the best tables at the elite Hollywood nightclubs where Paris Hilton and Leonardo DiCaprio hung out. When Google co-founder Larry Page married Richard Branson’s personal Caribbean island, we were there entertaining ourselves in a villa with John Cusack and watching beautiful women curl around Bono.

Justine Musk next to the house in Bel Air they shared with Elon

By this time, SpaceX already looked like a real aerospace company. She built and tested her engines and finished the full hull of the rocket. All Musk needed was to send it all up in the sky and see what happened.

Under normal circumstances, SpaceX could launch rockets from nearby Vandenberg Air Force Base. It had several launch sites to choose from, but none of the current tenants - neither Boeing, nor Lockheed, nor even the Air Force - were interested in helping the internet entrepreneur get into space. Locked up locally, SpaceX decided to try Kwajalein Island — or Kwaj — the largest island on the atoll between Guam and Hawaii, part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The U.S. Army used it for many years as a missile range. Gwynne Shotwell, then vice president of business development for SpaceX, found the colonel's name on the site and emailed him. Three weeks later, she received a call from the Army saying she would welcome SpaceX to the islands.

To get to Kwaja, SpaceX workers flew Musk's plane or commercial flights through Hawaii. The main accommodations were two-bedroom rooms, more like dormitories than hotel rooms, with prominent military desks and painting. Within months, a small team of people brushed the nearby island of Omelek to create a launch pad, and turned a large trailer into offices. The work took place in conditions of terrible humidity and in the sun, whose love could easily fry the skin through a T-shirt. The SpaceX team started at dawn, around 7am, and worked until 7pm.

“One or two people decided they were going to cook and made steaks and potatoes and pasta,” Hallman said. We had movies and a DVD player, and some even managed to fish in the docks. For many engineers, it was both a torture and a magical experience. “At Boeing, you’d be comfortable, but it shouldn’t be at SpaceX,” says Walter Sims, a SpaceX technical expert who took the time to get a diver certification right there on Quadge. We were all stars on that island. It was a pretty cheerful place.”

Time and time again, the missile was rolled onto the launch pad and placed vertically for a couple of days, so that during technical and safety checks, engineers identified new problems. As soon as possible, engineers returned the rocket to the hangar to protect it from the salt air. The teams, which had been working separately for months at SpaceX’s factory — on engines, avionics, software — had come together on the island to become a single, interdisciplinary entity.

Finally, on March 24, 2006, engineers fixed enough joints to start. The Falcon 1 stood on its square launch pad and smoked. Then he rushed to the sky and began to decrease in the great blue of the sky. At the control center on the island, Musk sat and watched the action in shorts, flip-flops and a T-shirt. Then, after 25 seconds, the Merlin engine caught fire and the car, which was flying straight, began to spin and fall. The Falcon 1 crashed right into the launch pad. The wreckage flew a hundred meters around, and the cargo bay broke through the roof of the SpaceX machine case and fell almost intact. Some engineers had to arm themselves with scuba diving equipment and catch the wreckage by assembling them into two large boxes.

After the rocket hit, there were quite a few men drinking in a bar on the main island. Musk wanted to take off again in the next six months, but to build a new car, it would take a huge amount of work. Musk has publicly vowed to build a working rocket, but people at the company and beyond have brainwashed the conclusion that SpaceX can only allow one try. However, if the financial situation and unnerved Musk, he almost never showed it to employees. “Elon has done a great job taking the burden of his worries off people,” says Branden Spikes, head of IT at SpaceX. He never underestimated the importance of success, but it wasn’t “if we fail, that’s it.” He was always optimistic.”

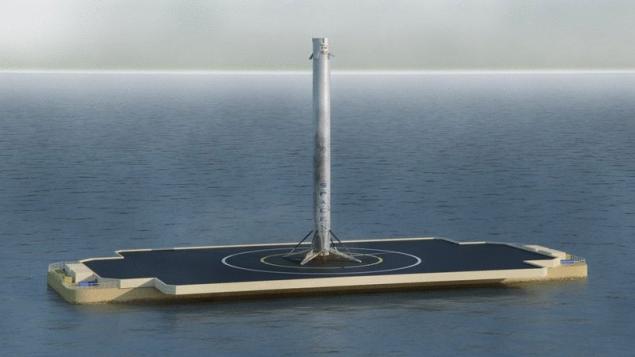

Meanwhile, SpaceX has assembled another team of engineers to work on a new Falcon 9 project, a nine-engine rocket that could be a possible replacement for the decommissioned shuttles. It will be years before SpaceX successfully launches them into space, but Musk was already aiming for expensive contracts with NASA.

In mid-2008, SpaceX prepared its fourth rocket for launch. Usually, the hull of the Falcon 1 went to Kwaj by barge. And while it may have sounded like a feverish decision, this time Musk and his engineers were too excited to wait for a long journey across the ocean. Musk rented a military cargo plane to take the missile hull from Los Angeles to Hawaii and then to Kwaj. The idea was fine if engineers hadn't forgotten what a pressure plane could do to a rocket body that was less than eight inches thick. When the plane went to Hawaii, strange sounds came from the cargo hold. "I looked back, expecting to see the scary thing," says Bulent Altan, the former head of SpaceX avionics. I told the pilot to get up and he started. The rocket crackled from high air pressure like an empty plastic bottle.

Altan realized that the SpaceX team on the plane had about 30 minutes to fix the problem before landing. They took out their pocket knives and cut the shrink film that covered the rocket. Then they found a set of tools on the plane and used the keys to turn a few nuts on the rocket so that its internal pressure balanced the pressure on the plane. After landing, the engineers contacted senior management and told what had happened. It was three in the morning in Los Angeles, and one of the executives decided to break the news to Musk.

At first glance, it would take three months to repair the rocket. The hull bent in several places, the internal partitions of the fuel tank, preventing the fuel from hanging out, broke. Musk ordered the team to move on to Kwaj and sent a team of repairmen with repair parts in pursuit. Two weeks later, the rocket was repaired. “It’s like you’re stuck in a foxhole,” Altan said. - You can't go out and miss the crawler behind you.

SpaceX's fourth and possibly final launch took place on September 28, 2008. SpaceX employees have been working tirelessly for months to bring this moment closer. They abandoned their families and were in exile at their tiny hot post - sometimes without the right food - for days on end, waiting for the launch window and coping with the cancellations that followed.

In the afternoon, the SpaceX team put the Falcon 1 in the launch position. The rocket stood tall as a bizarre artifact from the future, amid palm trees swaying nearby, and a small number of clouds crossed the impressive blue sky. By this point, SpaceX had turned every launch into an internet action, so people around the world were watching the company's actions. This time, the Falcon 1 was not loaded with real cargo: neither the company, nor the military, nor NASA wanted to see anything else disappear in an explosion at sea, so the rocket was loaded with a hundred kilograms of fake load.

Back in Los Angeles, Musk tried to distract himself from the mounting pressure by walking around Disneyland with his brother Kimbal and his children, but at 4pm he had to return to the SpaceX control center in Los Angeles to see it for himself. When the rocket roared and rushed upwards, the headquarters of SpaceX heard hoarse shouts of employees. Each successive step - clearing the island, checking the engines - was met with screaming and whistling. When the first stage fell off, the second flew for another 90 seconds, and staff drowned the webcast with their enthusiastic scream. "Fine," someone said. The Kestrel engine caught fire red and started its six-minute burn. “When the second stage burned out, I was finally able to breathe again and my knees stopped shaking,” said James McLory, a SpaceX engineer.

The fairing opened at the three-minute mark and fell to the ground. And after nine minutes of its journey, Falcon 1 also finished as planned. Six years later — four and a half years more than Musk had planned — the first privately-built liquid-fuel rocket reached orbit.

"Everyone cried," Kimbal says. It was one of the most emotional experiences of my life. Musk left the control center and went to the factory floor. "Well, it was damn amazing," he said. As the saying goes, “The fourth time is magical.”

However, the afterglow quickly disappeared. SpaceX, like Musk’s other company, Tesla, has faced a severe cash shortage. SpaceX needed to support the Falcon 9, as well as the construction of the Dragon capsule, which would one day carry cargo and then people to the International Space Station. Each project cost more than a billion dollars to complete, but SpaceX tried to build both machines simultaneously for a fraction of the cost. The company increased the pace of hiring and moved to a larger headquarters. SpaceX had planned a commercial launch of the satellite into orbit for the Malaysian government, but that launch and payment would not be until mid-2009. In parallel, SpaceX was just trying to pay the salary. It was when the company figured out how to put a rocket into space that it was on the verge of collapse.

And yet, as bad as they were, financial woes couldn't match the tragedy of Musk's personal life. Shortly after moving to Los Angeles, Musk lost his 10-week-old son, Alexander Nevada, to sudden infant death syndrome. “I don’t know why I want to talk about very sad things,” Musk said. - It's bad for the future. If you have other kids and commitments, immersing yourself in sadness won’t work well for everyone around you. I don’t know what to do in such situations.” Musk and Justine had five more sons — twins and triplets — but their relationship soured in 2008, and Musk filed for divorce.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: hi-news.ru

Ressi, a lanky eccentric, had long believed that his best friend was crazy or slightly moved, and put sticks in the wheels of the project. He bombarded Musk with references to videos of Russian, European and American rocket explosions. He was constantly bringing Musk’s friends together to talk him out of wasting money. But it didn't work. Musk confidently continued to finance the grand space spectacle and put a lot of effort into it. So Ressie had to go with Musk to Russia to follow Musk with good intentions.

Adeo took me aside and said, Elon is doing something crazy. A philanthropic gesture? It's crazy, Cantrell says. - He was seriously concerned.

The group agreed to meet with several companies such as Lavochkin’s NGO, which made Mars and Venus probes for the Russian Federal Space Agency, and Kosmotras, a commercial rocket launch organization with an office in Moscow. All meetings were held almost the same, in the best Russian traditions. Russian representatives of space companies, often skipping breakfast, like to schedule a meeting at 11 a.m. in the office with a small breakfast, eyewitnesses recall. Then there's a little chat for an hour or more while visitors are treated to sandwiches, sausages and, of course, vodka (let's not forget - it was 2001). After lunch there was a smoke break and coffee. And after all the tables had been cleared, a company representative would turn to Musk and ask, "So what purchase are you interested in?" The nervous tension would be less if the Russians took Musk more seriously. But they saw him as a newcomer who had just arrived in space and didn't take his bravado.

“One of their chief designers didn’t care about Elon and me because he thought we were stupid,” Cantrell said. Musk's team returned empty-handed.

In February 2002, the group returned to Russia, capturing Mike Griffin, who had worked at the CIA’s In-Q-Tel Venture Division and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and had just left Orbital Sciences, a satellite and spacecraft manufacturer. Now Musk wanted to take not one but three missiles and armed himself with a suitcase full of money. They met with representatives of Kosmotras in a beautiful and rich pre-revolutionary building in the suburbs of Moscow. The vodka toasts began with “For Space!” and “For America!”, and after a little wave, Musk asked directly how much the rocket would cost. Eight million dollars each, they said. Musk offered eight million for two. "They sat down and looked at him," Cantrell says, "and said something like "Boy." Nope. They also hinted that he had no money.” At this point, Musk decided that the Russians were either not serious about business negotiations, or wanted to squeeze the millionaire’s money to the maximum. He interrupted the meeting.

Overseas negotiators got out in the snow and blizzard of Moscow winter, caught a taxi and headed straight to the airport. The Russian missiles were the only ones that fit Musk’s budget, but they were too hard to work with. "The road was long," Cantrell recalls. We sat in silence watching Russian snowflakes fall into the snow. A gloomy mood persisted all the way to the plane until a cart of drinks pulled up. "The mood is always up when you take off from Moscow," Cantrell says. It’s like, ‘Oh my God, I did it.’ So Griffin and I took a drink and went nuts.” Musk sat in a row across from him and typed something on his computer. “We thought, ‘Here’s a jackass, what can he do now?’” At this point, Musk turned around and showed the table he had created.

"Hey, guys," he said, "I think we can build this rocket ourselves."

Just a few months ago, in June 2001, Musk turned thirty. "I'm not a child prodigy boy anymore," he told his wife and college sweetheart, Justine, either seriously or jokingly. Musk emigrated from South Africa in 1988 and made millions at two companies, Zip2 and PayPal. Now he was expected to act as a typical rich dotcom major and brew another web service. But Musk wanted more. As a child, he dreamed of spaceships and travel, greedily devouring Heinlein, Asimov and Douglas Adams. Most people would have had a triumph in Silicon Valley. But for Musk, it was just a stepping stone.

The change in his attitude and thinking was evident to friends, including a group of PayPal executives who gathered in Las Vegas one weekend to celebrate the recent sale. “We were hanging out at some Hard Rock Cafe house while Elon was reading some murky Soviet-era rocket science textbook, all shabby and seemingly bought on eBay,” said Kevin Hartz, one of PayPal’s early investors. He studied it and spoke openly about space travel and how the world would change.

Elon and Justine decided to move south to start a family and start a new chapter of their lives in Los Angeles. Unlike many seedlings from Southern California, they were made of technology. The mild, fitting weather made it ideal for the aviation industry, which had been there since the 1920s when Lockheed Martin opened a store in Hollywood. It was followed by Howard Hughes, the US Air Force, NASA, Boeing and others. Although Musk’s space plans were vague at the time, he was confident that he would find the right people for the space industry and persuade them to join his new venture.

Musk began with the collapse of the Mars Society, a unique collection of space enthusiasts who gathered to explore and explore the Red Planet. Each member of the society was raised 500 bucks to gather in the house of one of the honorary members of the Mars Society. What surprised Robert Zubrin, the head of the group, was the response of someone named Elon Musk, who was not invited by any member of the society.

“He gave us a check for $5,000,” Zubrin said. - Everyone paid attention to it.

Zubrin invited Musk for coffee before lunch and told him about a research center that the society had built in the Arctic to replicate the conditions of Mars, and about an experiment called the Translife Mission, during which a team of mice were to go into orbit. Mice had to give birth to babies under a gravity of one-third the size of Earth’s — like on Mars.

When it came time for lunch, Zubrin seated Musk in a place of honor next to himself, directed by James Cameron and Carol Stoker, a NASA planetary scientist. Musk was thrilled.

“He was much more active than other millionaires,” recalls Zubrin. He didn’t know much about space, but he had a scientific mindset. He wanted to know exactly what was planned for Mars and what the consequences might be.” Almost immediately, Musk joined the Mars Society and took a seat on the board. He donated an extra $100,000 to fund a research station in the desert.

Musk's friends at the time were not fully confident in Musk's mental health. He contracted malaria while on holiday in Africa and lost a lot of weight in the fight against it. Musk is only 185 centimeters tall, but he usually seems taller. He's broad-shouldered, tight-knit, stocky. True, the new version of the Mask, although slightly exhausted, but planned to do something important in his life.

“He said, logically, you have to move forward in the direction of the sun, but I have no idea how to make money from it,” said George Zachary, an investor and close friend of Musk. He started talking about space, and I thought he was talking about real offices and homes. In fact, Musk began to think about plans far beyond the plans of the Mars Society. Instead of sending mice into Earth orbit, Musk decided to send them to Mars.

"He asked if I thought it was crazy?" says Zachary. And I asked if the mice would come back. Because if they don't, most people will think it's crazy. Musk said that the mice will not only visit Mars, but will also return and bring offspring.

Musk built a network of space experts and gathered the best of them in a series of salons - sometimes at the Renaissance Hotel at Los Angeles Airport, sometimes at Sheratin in Palo Alto. Musk had no formal business plan. He mostly wanted to help them develop the idea of sending mice to Mars, or at least come up with something comparable. Musk hoped to demonstrate a beautiful gesture to humanity – to do something that would catch the world’s attention, make people think about Mars again, and reflect on human potential. There were also scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Cameron was, was Griffin. No one on the planet knew more about how to launch something into space than Griffin, and he advised Musk. He will be working with NASA in four years.

Experts were thrilled to have another rich guy who wants to fund something interesting in space. They were happy to discuss the possibilities and benefits of sending mice upstairs. But the conversation turned to another project, the Oasis of Mars. According to this scenario, Musk would buy a rocket and launch a robotic greenhouse on Mars, a plant-growing chamber that would open and take root in Martian regolith, or soil, and then set off in a lush color to produce Mars’ first oxygen. Much to Musk’s delight, the plan seemed feasible and promising.

Musk wanted the space greenhouse to be able to send videos back to Earth so people could watch the plants grow. The group also discussed the possibility of collecting kits from students across the country who want to grow their own plants and figure out, for example, that a Martian flower will grow twice as tall as its terrestrial relative over the same time period. Musk’s enthusiasm began to inspire a group of experts, many of whom were cynical about something new about space. There were engineering problems that needed to be solved. Taking Martian soil into a greenhouse looked not only physically challenging, but also problematic, as the soil could be toxic. For a while, scientists have discussed growing a plant in a nutrient gel, but it already looked like a hoax. Even optimistic moments are stuck in the unknown. One scientist found several tenacious mustard seeds and decided that they could survive the features of the Martian field.

"It wouldn't be nice if the plant died," says Dave Bearden, a space industry veteran who attended the meeting. Then you will have a dead garden on Mars.

Most of the space experts worried about the budget Musk. After the salons, it seemed that Musk was willing to spend 20-30 million dollars on all this, and everyone knew that just launching a rocket would eat all the money. But Musk had his own plans. He studied books he borrowed from Cantrell and others. There were "Elements of Rocket Propulsion", "Fundamentals of Astrodynamics", "Aerothermodynamics of Gas Turbine" and "Rocket Propulsion". According to Musk’s calculations, he could reduce the cost of an affordable rocket launch by building a small racket that can deliver small satellites and payload into space. Space Exploration Techologies, or SpaceX, was founded in June 2002. The beginning of the journey to Mars was laid.

SpaceX’s first headquarters is located in the old 1310 East Grand Avenue warehouse in El Segundo, a suburb of Los Angeles. There were 75,000 square meters of open space and several porches that allowed Musk to drive his silver McLaren F1 straight to the office. It was a hangar-like building with dusty floors and curved ceilings. Musk approached one of the cargo docks, raised the gate and unloaded the equipment on his own. Tables were scattered throughout the factory, so computer scientists and engineers designing machines could sit next to welders and locksmiths bringing these machines to life. For the aerospace industry, this was a bold decision. Ordinary aerospace companies separate engineers and machinists by thousands of kilometers.

SpaceX planned to do things differently. Instead of assembling parts by thousands of suppliers, a company should build as many machines as possible. This includes both a mobile launch pad and rocket engines, which is incredible. Wherever possible, SpaceX should be faster, cheaper and better than its competitors. It was supposed to launch a lot of rockets every month, receive money every month, and not depend on government money or major suppliers. SpaceX's first rocket was called the Falcon 1, after the "Millennial Falcon" from Star Wars. And at a time when launching 250 kilograms of payload into orbit cost $30 million, Musk promised that the Falcon 1 would be able to lift 750 kilograms for $6.9 million.

The proposed timetable for the aerospace industry’s upheaval was ridiculously short. One of SpaceX's first presentations promised the first completed engine by May 2003, a second engine by June, a rocket hull by July and a full assembly by August. The launch pad was supposed to be ready by September, and the first launch of the rocket will take place, they say, in November 2003, 15 months after the creation of the company. The trip to Mars was supposed to take place in ten years. "Elon has always been an optimist," says Kevin Brogan, an early SpaceX employee. That is the best word to describe him. He can lie about when everything should be ready. He will choose the most aggressive term possible, confident that everything will go according to plan, and then fit everyone, believing that everyone should work even faster.”

Musk looked for young and active people, personally called the best students of aerospace institutes and hired them on the phone. "I thought it was a phone divorce," says Michael Colonno, whom Musk contacted while a Stanford student. I didn’t believe for a minute that he had a rocket company. But when students searched for Musk’s name online, hiring them at SpaceX became incredibly easy. After hearing about SpaceX’s ambitions, top engineers from Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Orbital Sciences also flowed into the upstart company.

For the first year at SpaceX, one or two new employees joined each week. Brogan became employee number 23 and came from TRW, an aerospace company that failed to form, where he was hampered by various internal policies, preventing him from working. “I called it a country club. Nobody did anything.” Brogan started working for SpaceX a day after the interview. He was told to stagger around the office and find a computer. "Then I had to go to Fry's store, get everything I needed, and then to Staples for a chair."

One of the first projects was the construction of a gas generator, such a small rocket engine that produces hot gas to power pumps. Tom Mueller, another TRW veteran, Tim Buzza, a defector from Boeing, and several other young engineers assembled a generator in Los Angeles, then packed it in a pickup truck and drove it to Mojave for testing. The Mojave Desert was 100 kilometers from Los Angeles and later became the center of aerospace companies like Scaled Composites and XCOR.

The SpaceX team borrowed the test bench from XCOR, its dimensions were ideal for a gas generator. The first launch took place at 11am and lasted 90 seconds. The generator worked, but released a black cloud that settled directly above the airport tower. In the days that followed, SpaceX engineers perfected a procedure that allowed them to run many tests a day - an unheard-of practice at the airport - and got the right gas generator after a couple of weeks of work.

The SpaceX team made several trips to Mojave and other locations, including a testbed at Edwards Air Force Base in Southern California and another in Mississippi. During this tour, SpaceX engineers visited a 300-acre test site in McGregor, Texas. It's left over from fellow billionaire Andrew Beal, who winded down his aerospace startup after pouring millions into a massive test site. SpaceX engineers fell in love with the place - and a three-story concrete stand - and persuaded Musk to buy it.

Jeremy Hallman, a young engineer, soon found himself living in Texas. Hallman embodies an example of the recruits Musk needed: he earned an aerospace engineer degree from the University of Iowa and a master’s degree in astronautics from the University of Southern California. He spent several years as a test engineer at Boeing, working with engines, rockets and spacecraft. At 23, Hallman was young, single and ready to devote any part of his life to working for SpaceX. He was second on Mueller's team.

Müller developed several three-dimensional computer models of the two engines he wanted to build. The Merlin was to be the Falcon 1 first-stage engine to tear the rocket off the ground, and the Kestrel was to be the small second-stage engine to drive it in space. Together, Hallman and Mueller have determined which parts SpaceX will build at the Los Angeles factory and which will try to buy. In the case of purchase parts, Hallman had to go to different machine shops and clarify the timing and delivery plans of the equipment. Quite often, sellers have told Hallman that SpaceX's timeline is pretty tight. Others were more agile and tried to adapt existing products to SpaceX’s needs, rather than building something from scratch. Hallman also found that ingenuity did a good job. He found, in particular, that if you replace several seals on the valves of car washers, they can be used with rocket fuel.

In addition to building its own engines, fuselages and capsules, SpaceX has developed its own motherboards and chips, vibration detection sensors, flight computers and solar panels. In the case of radio, SpaceX engineers have found that they can reduce the weight of the device by 20%. The overall savings were incredible, with the price of industrial-grade equipment used by aerospace companies dropping from $50,000 to $100,000 to $5,000 per SpaceX unit.

Even while working on Falcon 1, Musk planned to build something big, a Big Falcon Rocket. It would have the largest rocket engine in history. Musk’s focus on “bigger and faster” has amused and surprised some SpaceX suppliers, who have occasionally helped the company, such as Barber-Nichols, a Colorado manufacturer of turbopumps for rocket engines and other aerospace equipment. Bob Linden, an employee at Barber-Nichols, recalls those days.

"Elon showed up with Tom Mueller and started telling us that he was meant to launch things into space at a low cost and help us become spacefaring humans," he says. We weren't sure if Elon should be taken seriously. They started asking for the impossible. They needed a turbo pump that could be built in less than a year for less than $1 million. Boeing typically does such projects for five years and $100 million. Tom asked us to do our best, and we built it in 13 months. He was relentless.

After SpaceX built its first engine in a factory in California, Hallman loaded it with other equipment in a U-Haul trailer, hooked it to a white Hummer. H2 and drove from Los Angeles to the test site in Texas. Among the rattlesnakes, ants, insulation and incinerating heat, a group of engineers delivered the prototype engine to its place, filled it with liquid oxygen and kerosene, hid in a bunker behind an earthshaft and warmed it up for 0.1 seconds. The bad news was that it was a hell of a job. The good news was that nothing exploded. (This will happen later, and engineers will have a term for this case: Rapid unscheduled disassembly, RUD, rapid unplanned disassembly.) After the first successful burn, employees consecrated the site by drinking a $1,200 bottle of Remi Martin left over from a SpaceX initiation party from paper cups.

Over the next few years, the road from California to the test site will become known as the Texas Cattle Haul (literally the Texas Cattle Way). Engineers had to work 10 consecutive days in Texas, return to California for the weekend and then back. To ease the burden of travel, Musk sometimes allowed him to take his private jet. “It accommodated six,” Mueller says. “Seven, if someone sits in the toilet, it happens all the time.”

Tesla Motors Musk, of course, wasn’t just building rockets. In 2003, a year after he launched SpaceX, Musk co-founded Tesla Motors, which planned to sell sports electric cars. Musk has long dreamed of a good electric car, and although he has already invested $100 million in SpaceX, he has had to invest another $70 million in Tesla and become the company’s CEO. This decision almost ruined both companies.

While preparing for the filming of Iron Man in early 2007, director John Favreau rented a Los Angeles complex that was once owned by Hughes Aircraft, an aerospace and defense contractor founded 80 years ago by Howard Hughes. This facility had a series of interconnected hangars and served as the production base for the film. He also provided Robert Downey Jr., who played the role of Tony Stark, the creator of Iron Man, with plenty of inspiration. Downey looked with nostalgia at one of the large hangars, brought to an emergency condition. Not long ago, this building served as home to big ideas from a big man who shook the industry and wilfully did his thing.

Downey has heard of a man like Howard Hughes who will build his own industrial complex fifteen kilometers from the filming site of Iron Man. Instead of imagining what Hughes' life might have been like, Downey was given the opportunity to plunge into a more realistic environment. In March 2007, he visited SpaceX’s El Segundo headquarters and received an individual tour from Musk. "It's not easy to surprise me, but this place and this guy were amazing," Downey said.

In Downey’s eyes, the SpaceX factory looked like a giant, exotic hardware store. Everywhere there were enthusiastic employees working with an assortment of cars. Young white-collar engineers worked with blue-collar assembly line workers, and all seemed to share a genuine fascination with what they were doing. “The company was like an active startup,” Downey said. After the initial tour, Downey left, pleased with SpaceX's resemblance to Hughes' former factory.

The men took a walk, sat down in Musk's office and had lunch. Downey noted that Musk was not a foul-smelling, fussy and busy coder. Downey felt that Musk was one of those eccentric directors who could work with people in the factory. When Downey returned to the office where he was working on the film, he asked Favreau to place a Tesla Roadster in Tony Stark's studio. "After meeting Elon and his performance for me, I decided I would need his presence in the workshop," Downey says. - They became contemporaries. Elon was one of the people Tony used to hang out and have fun with, or even suddenly go into the wild jungle to drink potions with shamans. Musk later made a cameo appearance in Iron Man 2.

Musk has enjoyed his promotion. Together with Justine, they bought a house in Bel Air. Their neighbors were Quincy Jones and Joy Francis, creator of the Girls Gone Wild video. Musk and several former PayPal employees produced "Thank You for Smoking" and used Musk's plane in the film. Not being a coutile, Musk was involved in Hollywood nightlife and his social scene. "We had a household staff of five; by day the house turned into a workplace," Justine wrote in an article for Marie Claire. We entered the black tie club and got the best tables at the elite Hollywood nightclubs where Paris Hilton and Leonardo DiCaprio hung out. When Google co-founder Larry Page married Richard Branson’s personal Caribbean island, we were there entertaining ourselves in a villa with John Cusack and watching beautiful women curl around Bono.

Justine Musk next to the house in Bel Air they shared with Elon

By this time, SpaceX already looked like a real aerospace company. She built and tested her engines and finished the full hull of the rocket. All Musk needed was to send it all up in the sky and see what happened.

Under normal circumstances, SpaceX could launch rockets from nearby Vandenberg Air Force Base. It had several launch sites to choose from, but none of the current tenants - neither Boeing, nor Lockheed, nor even the Air Force - were interested in helping the internet entrepreneur get into space. Locked up locally, SpaceX decided to try Kwajalein Island — or Kwaj — the largest island on the atoll between Guam and Hawaii, part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The U.S. Army used it for many years as a missile range. Gwynne Shotwell, then vice president of business development for SpaceX, found the colonel's name on the site and emailed him. Three weeks later, she received a call from the Army saying she would welcome SpaceX to the islands.

To get to Kwaja, SpaceX workers flew Musk's plane or commercial flights through Hawaii. The main accommodations were two-bedroom rooms, more like dormitories than hotel rooms, with prominent military desks and painting. Within months, a small team of people brushed the nearby island of Omelek to create a launch pad, and turned a large trailer into offices. The work took place in conditions of terrible humidity and in the sun, whose love could easily fry the skin through a T-shirt. The SpaceX team started at dawn, around 7am, and worked until 7pm.

“One or two people decided they were going to cook and made steaks and potatoes and pasta,” Hallman said. We had movies and a DVD player, and some even managed to fish in the docks. For many engineers, it was both a torture and a magical experience. “At Boeing, you’d be comfortable, but it shouldn’t be at SpaceX,” says Walter Sims, a SpaceX technical expert who took the time to get a diver certification right there on Quadge. We were all stars on that island. It was a pretty cheerful place.”

Time and time again, the missile was rolled onto the launch pad and placed vertically for a couple of days, so that during technical and safety checks, engineers identified new problems. As soon as possible, engineers returned the rocket to the hangar to protect it from the salt air. The teams, which had been working separately for months at SpaceX’s factory — on engines, avionics, software — had come together on the island to become a single, interdisciplinary entity.

Finally, on March 24, 2006, engineers fixed enough joints to start. The Falcon 1 stood on its square launch pad and smoked. Then he rushed to the sky and began to decrease in the great blue of the sky. At the control center on the island, Musk sat and watched the action in shorts, flip-flops and a T-shirt. Then, after 25 seconds, the Merlin engine caught fire and the car, which was flying straight, began to spin and fall. The Falcon 1 crashed right into the launch pad. The wreckage flew a hundred meters around, and the cargo bay broke through the roof of the SpaceX machine case and fell almost intact. Some engineers had to arm themselves with scuba diving equipment and catch the wreckage by assembling them into two large boxes.

After the rocket hit, there were quite a few men drinking in a bar on the main island. Musk wanted to take off again in the next six months, but to build a new car, it would take a huge amount of work. Musk has publicly vowed to build a working rocket, but people at the company and beyond have brainwashed the conclusion that SpaceX can only allow one try. However, if the financial situation and unnerved Musk, he almost never showed it to employees. “Elon has done a great job taking the burden of his worries off people,” says Branden Spikes, head of IT at SpaceX. He never underestimated the importance of success, but it wasn’t “if we fail, that’s it.” He was always optimistic.”

Meanwhile, SpaceX has assembled another team of engineers to work on a new Falcon 9 project, a nine-engine rocket that could be a possible replacement for the decommissioned shuttles. It will be years before SpaceX successfully launches them into space, but Musk was already aiming for expensive contracts with NASA.

In mid-2008, SpaceX prepared its fourth rocket for launch. Usually, the hull of the Falcon 1 went to Kwaj by barge. And while it may have sounded like a feverish decision, this time Musk and his engineers were too excited to wait for a long journey across the ocean. Musk rented a military cargo plane to take the missile hull from Los Angeles to Hawaii and then to Kwaj. The idea was fine if engineers hadn't forgotten what a pressure plane could do to a rocket body that was less than eight inches thick. When the plane went to Hawaii, strange sounds came from the cargo hold. "I looked back, expecting to see the scary thing," says Bulent Altan, the former head of SpaceX avionics. I told the pilot to get up and he started. The rocket crackled from high air pressure like an empty plastic bottle.

Altan realized that the SpaceX team on the plane had about 30 minutes to fix the problem before landing. They took out their pocket knives and cut the shrink film that covered the rocket. Then they found a set of tools on the plane and used the keys to turn a few nuts on the rocket so that its internal pressure balanced the pressure on the plane. After landing, the engineers contacted senior management and told what had happened. It was three in the morning in Los Angeles, and one of the executives decided to break the news to Musk.

At first glance, it would take three months to repair the rocket. The hull bent in several places, the internal partitions of the fuel tank, preventing the fuel from hanging out, broke. Musk ordered the team to move on to Kwaj and sent a team of repairmen with repair parts in pursuit. Two weeks later, the rocket was repaired. “It’s like you’re stuck in a foxhole,” Altan said. - You can't go out and miss the crawler behind you.

SpaceX's fourth and possibly final launch took place on September 28, 2008. SpaceX employees have been working tirelessly for months to bring this moment closer. They abandoned their families and were in exile at their tiny hot post - sometimes without the right food - for days on end, waiting for the launch window and coping with the cancellations that followed.

In the afternoon, the SpaceX team put the Falcon 1 in the launch position. The rocket stood tall as a bizarre artifact from the future, amid palm trees swaying nearby, and a small number of clouds crossed the impressive blue sky. By this point, SpaceX had turned every launch into an internet action, so people around the world were watching the company's actions. This time, the Falcon 1 was not loaded with real cargo: neither the company, nor the military, nor NASA wanted to see anything else disappear in an explosion at sea, so the rocket was loaded with a hundred kilograms of fake load.

Back in Los Angeles, Musk tried to distract himself from the mounting pressure by walking around Disneyland with his brother Kimbal and his children, but at 4pm he had to return to the SpaceX control center in Los Angeles to see it for himself. When the rocket roared and rushed upwards, the headquarters of SpaceX heard hoarse shouts of employees. Each successive step - clearing the island, checking the engines - was met with screaming and whistling. When the first stage fell off, the second flew for another 90 seconds, and staff drowned the webcast with their enthusiastic scream. "Fine," someone said. The Kestrel engine caught fire red and started its six-minute burn. “When the second stage burned out, I was finally able to breathe again and my knees stopped shaking,” said James McLory, a SpaceX engineer.

The fairing opened at the three-minute mark and fell to the ground. And after nine minutes of its journey, Falcon 1 also finished as planned. Six years later — four and a half years more than Musk had planned — the first privately-built liquid-fuel rocket reached orbit.

"Everyone cried," Kimbal says. It was one of the most emotional experiences of my life. Musk left the control center and went to the factory floor. "Well, it was damn amazing," he said. As the saying goes, “The fourth time is magical.”

However, the afterglow quickly disappeared. SpaceX, like Musk’s other company, Tesla, has faced a severe cash shortage. SpaceX needed to support the Falcon 9, as well as the construction of the Dragon capsule, which would one day carry cargo and then people to the International Space Station. Each project cost more than a billion dollars to complete, but SpaceX tried to build both machines simultaneously for a fraction of the cost. The company increased the pace of hiring and moved to a larger headquarters. SpaceX had planned a commercial launch of the satellite into orbit for the Malaysian government, but that launch and payment would not be until mid-2009. In parallel, SpaceX was just trying to pay the salary. It was when the company figured out how to put a rocket into space that it was on the verge of collapse.

And yet, as bad as they were, financial woes couldn't match the tragedy of Musk's personal life. Shortly after moving to Los Angeles, Musk lost his 10-week-old son, Alexander Nevada, to sudden infant death syndrome. “I don’t know why I want to talk about very sad things,” Musk said. - It's bad for the future. If you have other kids and commitments, immersing yourself in sadness won’t work well for everyone around you. I don’t know what to do in such situations.” Musk and Justine had five more sons — twins and triplets — but their relationship soured in 2008, and Musk filed for divorce.

P.S. And remember, just by changing your consciousness – together we change the world!

Source: hi-news.ru

Sugar – fuel for the growth of cancer cells

How to discover a creative person or for the suppression of internal bores