1059

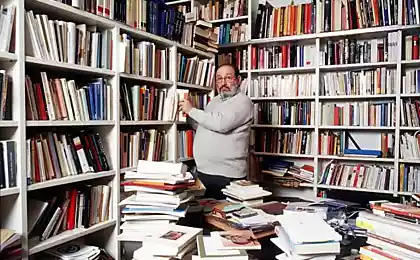

"To say almost the same thing": Umberto Eco on translation difficulties

The translation cannot convey all shades of meaning and stylistic peculiarities of the original. Translator to remain faithful to the author's text, always have to sacrifice something. According to Umberto Eco, translation, therefore, is always only the result of the negotiations, but in any case not the result of authorial or editorial ultimatum.

Two million eight hundred fifty two thousand one hundred twenty two

vilaser.se/

Excerpt from the book the Italian philosopher "to Say almost the same thing," in which he reflects on the compromise nature of translation, indistinguishable from the standpoint of pure theory.

What do you mean "translate"? The first answer, and, moreover, reassuring, could be this: to say the same thing in another language. However, we experienced considerable difficulties in trying to establish what it means to "say the same", and clearly recognize that in the course of operations such as paraphrase, definition, explanation, restatement, not to mention the alleged synonymous substitutions. Second, holding before him the text to be translated, we don't know what that is. Finally, in some cases, it is doubtful even the meaning of a word to say.

We do not intend to emphasize the Central position of the translation problem in many philosophical discussions and, therefore, will not be taken for search of the answer to the question of whether there is a kind of Thing in his "Iliad" or "Night song of a shepherd, wandering in Asia"* (the Thing-in-Itself, which seemingly needs to Shine or flashing out and over the top of any language into which they are translated), or, on the contrary, it is impossible to reach, despite all the efforts, which will resort to another language. Fly so high we can not afford, and in later pages we shall often come down lower.

Put in the English novel, a character says: it's raining cats and dogs. Bad is the translator, who, thinking that says the same thing, translate it literally: "it's raining dogs and cats" (piove cani e gatti). This should be translated "it's raining" (piove and piove cantinelle or saute Dio la manda). But what if it's a fantastic novel, and wrote him an adherent of the so-called "portiansky" science*, and it tells how the rain really is pouring cats and dogs? Then you need to translate literally. Consonant. What if this character goes to see Dr. Freud to tell him that experiencing unexplained maniacal fear of cats and dogs, which, as it seems, become particularly dangerous when it rains? To translate again, you need to be literally, but lost a certain shade of meaning: this Cat Person is also concerned about idiomatic expressions.

To say almost the same thing is a procedure which takes place under the sign peregovorov if in the Italian novel character, saying that it's raining cats and dogs, is a student at the Berlitz school*, not able to resist the temptation to decorate his speech with anglicisms labored? If translated literally, ignorant Italian reader would not understand that this character uses the anglicism. But if then this Italian novel will need to be translated in English, how to transfer this habit to usadate his speech with anglicisms? Do we have to change the nationality of the hero and make him an Englishman, the right and left rolling italianissimi, or the London workers, to no avail demonstrating an Oxford accent? It would be an inexcusable liberty. But if the phrase it's raining cats and dogs speaks English character of the French novel? How to translate it into English? See how hard it is to say, what is that which must be transmitted through text, and how difficult it is to pass it.

This is the meaning of the following chapters: to try to understand how, even knowing that the same is never said, you can say almost the same thing.

In Genet (Genette 1982) rightly compares the translation with the palimpsest, i.e. a parchment from which "scraped" off of the original inscription to put on a different, but old writing still shines through the new, and it can be read. As for this "almost", Petrilli (Petrilli 2001) titled a collection of articles on translation: Lo stesso altro ("same different").

In this approach, the problem is not so much in the concept of the same and not so much in concept the same as in the concept that almost*. How loose is almost? It all depends on point of view: the Earth is almost the same as Mars because both planets revolve around the Sun and both are spherical. But the Earth may be almost the same as any other planet orbiting some other solar system; it is almost the same as the Sun itself, since we are talking about celestial bodies; it is almost the same as the crystal ball of the fortune teller, like a ball or orange.

To establish the limits of flexibility, extensibility, this almost requires some criteria, which are pre-negotiated. To say almost the same thing is a procedure which, as we shall see below, is marked by negotiations.

* A large number of examples is explained not only by didactic considerations. It is necessary to translate General thoughts on translation (or even number of reflections of a normative nature) go to the local analysis given in the power of persuasion that the transfers are related to the texts, and each text poses problems, from each other great. Cm. about this: Calabresi 2000.

Texts for translation studies often did not satisfy me because in them the richness of theoretical reasoning is not reliable clothed in the armor examples. Of course, this applies not to all books or essays on this subject, and I think, for example, about how the wealth of examples collected in the book George Steiner's "After Babel" (Steiner 1975). But in many other cases, I have a suspicion that the theorist of translation itself is never translated, and because talking about what you don't have direct experience*.

Once Giuseppe Francescato dropped the remark (paraphrasing from memory): to study the phenomenon of bilingualism, and therefore, to gather enough experience about the formation of dual language competence, need hour after hour, day after day to observe the behavior of the child who is forced to have a dual linguistic motivation.

This experience can be acquired only: (1) linguists, (2) having a spouse of another nationality and / or living abroad, (3) having children and (4) is able to regularly monitor their children from the very first moments of their linguistic behavior. To comply with all these requirements is not always possible, and that is why the study of bilingualism was slow to develop.

I ask myself the following question: perhaps, in order to develop a theory of translation, it is necessary not only to consider the many examples of translation, but to produce at least one of the following three experiments: to compare the translations made by others, to translate and to be translated (or, even better, be translated, working with their own interpreter)?

To engage in theoretical reflection on the translation process, it is useful to have it active or passive opetatud one would notice that it is not necessary to be a poet to develop a sensible theory of poetry, and it is possible to evaluate a text written in a foreign language, even though this language is mainly passive. However, this objection is only true to a certain extent. In fact, even those who never wrote poetry, has experience of their own language and could at least once in your life to try (and always try) to write odinnadtsatiklassnikov, a rhyme, a metaphor to depict a particular object or event. And one who has only a passive knowledge of a foreign language, at least, tested by experience, how difficult is it to build a collapsible phrase. It also seems to me that the critic-the critic who can't draw, capable of (and why) to note the complexity inherent in any form of visual image; similarly, a critic and musicologist, with a weak voice, can direct experience to understand what skills you need to expertly take a high note.

So I think of it like to engage in theoretical reflection on the translation process, it is useful to have it active or passive experience. On the other hand, when there is no theory of translation did not exist, that is, from St. Jerome to the XX century, the only interesting observations on this subject were made by those who translated it myself, and quite aware of the hermeneutic difficulties experienced by St. Augustine, intending to argue about the correct translation, but while possessing a weak knowledge of foreign languages (Hebrew he did not know at all, but Greek is very weak).

In recent decades there has been a lot of works on translation theory, including because of increased number of research centres, courses and departments dedicated to this issue, as well as schools of translation and interpretation. The reasons for the growth of interest in translation are numerous, but they converge: on the one hand, this phenomenon of globalization, increasingly closer to each other as whole groups and individual representatives of the human race, speaking different languages, then the development of interest in semiotics, thanks to which the concept of translation becomes Central, even if it is not expressed directly (recall the discussion about the meaning of the statement, which must "survive" the transition from one language to another), and finally, the proliferation of computer science, inducing many to attempt the creation and further development of models of artificial translation (translational problem becomes crucial — not so much in the first half of the XX century and was later developed such theories of the structure of language (or speakers of languages), which focused on the phenomenon of the impossibility of radical translation. It's a tough nut to crack and the theorists who are developing these theories, be aware of the fact that people transfer, and for thousands of years.

Sixty five million three hundred fifty two thousand four hundred forty four

Vulgate — an honorific title appended to the Latin translation of the Holy Scriptures. The first Biblia Vulgata was written by a teacher of the Church by Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus.

Perhaps they are poorly translated and do here, you might think about the discussions, all the while disturbing the environment of the scholars, tend to constantly criticize previous translations of the sacred texts. However, no matter how insolvent and failed or translations, where the texts of the old and New Testaments came to billions of believers who speak different languages, in this relay from one language to another, from one Vulgate to another large part of humanity was in agreement regarding the basic facts and events referred to in any of these texts, from the Ten commandments to the sermon on the mount, from the stories about Moses to the Passion of Christ, and I would like to say regarding spirit, which animates these texts.

The translation is based on a sort of negotiation, because they are such a basic process in which, in order to obtain something, reject something gregoropoulos, even when legal almost categorically affirms the thesis about the impossibility of translation, in practice we are always faced with the paradox of Achille and the tortoise: theoretically, Achilles will never overtake the tortoise, but in reality, as taught by experience, he overtake her. Put, the theory is inspired by the purity, without which experience could do; however, an interesting problem is how and what the experience can do without it. Hence the idea that translation is based on a sort of negotiation, because they are such a basic process in which, in order to obtain something, abandon something else; and, ultimately, Contracting parties should emerge from this process with a sense of reasonable and mutual satisfaction, mindful of the Golden rule, according to which it is impossible to have it all.

Here one might ask, what are the Contracting parties in this negotiation process. A lot of them, even if sometimes they lack initiative: on the one hand, there is the source with their Autonomous rights, and sometimes the shape of the empirical the author (still alive) and his possible claims to control, as well as all the culture in which this text is born; on the other hand, there is the text of arrival and the culture in which it appears, with the system's expectations of his prospective readers, and sometimes even with the publishing industry, foreseeing the different criteria of translation in matter, which creates the text: for strict philological series or for a collection of entertaining books. The publisher may even require that the translated detective novel in Russian was removed diacritical marks are used when transferring character names to make it easier for readers to identify and remember them. The interpreter acts as the person conducting the negotiations between the actual or potential parties to such negotiations prior Express consent of the parties is not always expected.

However, some implicit negotiations take place in the covenants about accuracy, and they are different for readers who undertake the history books, and for those who read the novels: in force of the agreement, existing for thousands of years, the latter can provide a temporary exemption from the obligation to Express incredulity. published

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: theoryandpractice.ru

Two million eight hundred fifty two thousand one hundred twenty two

vilaser.se/

Excerpt from the book the Italian philosopher "to Say almost the same thing," in which he reflects on the compromise nature of translation, indistinguishable from the standpoint of pure theory.

What do you mean "translate"? The first answer, and, moreover, reassuring, could be this: to say the same thing in another language. However, we experienced considerable difficulties in trying to establish what it means to "say the same", and clearly recognize that in the course of operations such as paraphrase, definition, explanation, restatement, not to mention the alleged synonymous substitutions. Second, holding before him the text to be translated, we don't know what that is. Finally, in some cases, it is doubtful even the meaning of a word to say.

We do not intend to emphasize the Central position of the translation problem in many philosophical discussions and, therefore, will not be taken for search of the answer to the question of whether there is a kind of Thing in his "Iliad" or "Night song of a shepherd, wandering in Asia"* (the Thing-in-Itself, which seemingly needs to Shine or flashing out and over the top of any language into which they are translated), or, on the contrary, it is impossible to reach, despite all the efforts, which will resort to another language. Fly so high we can not afford, and in later pages we shall often come down lower.

Put in the English novel, a character says: it's raining cats and dogs. Bad is the translator, who, thinking that says the same thing, translate it literally: "it's raining dogs and cats" (piove cani e gatti). This should be translated "it's raining" (piove and piove cantinelle or saute Dio la manda). But what if it's a fantastic novel, and wrote him an adherent of the so-called "portiansky" science*, and it tells how the rain really is pouring cats and dogs? Then you need to translate literally. Consonant. What if this character goes to see Dr. Freud to tell him that experiencing unexplained maniacal fear of cats and dogs, which, as it seems, become particularly dangerous when it rains? To translate again, you need to be literally, but lost a certain shade of meaning: this Cat Person is also concerned about idiomatic expressions.

To say almost the same thing is a procedure which takes place under the sign peregovorov if in the Italian novel character, saying that it's raining cats and dogs, is a student at the Berlitz school*, not able to resist the temptation to decorate his speech with anglicisms labored? If translated literally, ignorant Italian reader would not understand that this character uses the anglicism. But if then this Italian novel will need to be translated in English, how to transfer this habit to usadate his speech with anglicisms? Do we have to change the nationality of the hero and make him an Englishman, the right and left rolling italianissimi, or the London workers, to no avail demonstrating an Oxford accent? It would be an inexcusable liberty. But if the phrase it's raining cats and dogs speaks English character of the French novel? How to translate it into English? See how hard it is to say, what is that which must be transmitted through text, and how difficult it is to pass it.

This is the meaning of the following chapters: to try to understand how, even knowing that the same is never said, you can say almost the same thing.

In Genet (Genette 1982) rightly compares the translation with the palimpsest, i.e. a parchment from which "scraped" off of the original inscription to put on a different, but old writing still shines through the new, and it can be read. As for this "almost", Petrilli (Petrilli 2001) titled a collection of articles on translation: Lo stesso altro ("same different").

In this approach, the problem is not so much in the concept of the same and not so much in concept the same as in the concept that almost*. How loose is almost? It all depends on point of view: the Earth is almost the same as Mars because both planets revolve around the Sun and both are spherical. But the Earth may be almost the same as any other planet orbiting some other solar system; it is almost the same as the Sun itself, since we are talking about celestial bodies; it is almost the same as the crystal ball of the fortune teller, like a ball or orange.

To establish the limits of flexibility, extensibility, this almost requires some criteria, which are pre-negotiated. To say almost the same thing is a procedure which, as we shall see below, is marked by negotiations.

* A large number of examples is explained not only by didactic considerations. It is necessary to translate General thoughts on translation (or even number of reflections of a normative nature) go to the local analysis given in the power of persuasion that the transfers are related to the texts, and each text poses problems, from each other great. Cm. about this: Calabresi 2000.

Texts for translation studies often did not satisfy me because in them the richness of theoretical reasoning is not reliable clothed in the armor examples. Of course, this applies not to all books or essays on this subject, and I think, for example, about how the wealth of examples collected in the book George Steiner's "After Babel" (Steiner 1975). But in many other cases, I have a suspicion that the theorist of translation itself is never translated, and because talking about what you don't have direct experience*.

Once Giuseppe Francescato dropped the remark (paraphrasing from memory): to study the phenomenon of bilingualism, and therefore, to gather enough experience about the formation of dual language competence, need hour after hour, day after day to observe the behavior of the child who is forced to have a dual linguistic motivation.

This experience can be acquired only: (1) linguists, (2) having a spouse of another nationality and / or living abroad, (3) having children and (4) is able to regularly monitor their children from the very first moments of their linguistic behavior. To comply with all these requirements is not always possible, and that is why the study of bilingualism was slow to develop.

I ask myself the following question: perhaps, in order to develop a theory of translation, it is necessary not only to consider the many examples of translation, but to produce at least one of the following three experiments: to compare the translations made by others, to translate and to be translated (or, even better, be translated, working with their own interpreter)?

To engage in theoretical reflection on the translation process, it is useful to have it active or passive opetatud one would notice that it is not necessary to be a poet to develop a sensible theory of poetry, and it is possible to evaluate a text written in a foreign language, even though this language is mainly passive. However, this objection is only true to a certain extent. In fact, even those who never wrote poetry, has experience of their own language and could at least once in your life to try (and always try) to write odinnadtsatiklassnikov, a rhyme, a metaphor to depict a particular object or event. And one who has only a passive knowledge of a foreign language, at least, tested by experience, how difficult is it to build a collapsible phrase. It also seems to me that the critic-the critic who can't draw, capable of (and why) to note the complexity inherent in any form of visual image; similarly, a critic and musicologist, with a weak voice, can direct experience to understand what skills you need to expertly take a high note.

So I think of it like to engage in theoretical reflection on the translation process, it is useful to have it active or passive experience. On the other hand, when there is no theory of translation did not exist, that is, from St. Jerome to the XX century, the only interesting observations on this subject were made by those who translated it myself, and quite aware of the hermeneutic difficulties experienced by St. Augustine, intending to argue about the correct translation, but while possessing a weak knowledge of foreign languages (Hebrew he did not know at all, but Greek is very weak).

In recent decades there has been a lot of works on translation theory, including because of increased number of research centres, courses and departments dedicated to this issue, as well as schools of translation and interpretation. The reasons for the growth of interest in translation are numerous, but they converge: on the one hand, this phenomenon of globalization, increasingly closer to each other as whole groups and individual representatives of the human race, speaking different languages, then the development of interest in semiotics, thanks to which the concept of translation becomes Central, even if it is not expressed directly (recall the discussion about the meaning of the statement, which must "survive" the transition from one language to another), and finally, the proliferation of computer science, inducing many to attempt the creation and further development of models of artificial translation (translational problem becomes crucial — not so much in the first half of the XX century and was later developed such theories of the structure of language (or speakers of languages), which focused on the phenomenon of the impossibility of radical translation. It's a tough nut to crack and the theorists who are developing these theories, be aware of the fact that people transfer, and for thousands of years.

Sixty five million three hundred fifty two thousand four hundred forty four

Vulgate — an honorific title appended to the Latin translation of the Holy Scriptures. The first Biblia Vulgata was written by a teacher of the Church by Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus.

Perhaps they are poorly translated and do here, you might think about the discussions, all the while disturbing the environment of the scholars, tend to constantly criticize previous translations of the sacred texts. However, no matter how insolvent and failed or translations, where the texts of the old and New Testaments came to billions of believers who speak different languages, in this relay from one language to another, from one Vulgate to another large part of humanity was in agreement regarding the basic facts and events referred to in any of these texts, from the Ten commandments to the sermon on the mount, from the stories about Moses to the Passion of Christ, and I would like to say regarding spirit, which animates these texts.

The translation is based on a sort of negotiation, because they are such a basic process in which, in order to obtain something, reject something gregoropoulos, even when legal almost categorically affirms the thesis about the impossibility of translation, in practice we are always faced with the paradox of Achille and the tortoise: theoretically, Achilles will never overtake the tortoise, but in reality, as taught by experience, he overtake her. Put, the theory is inspired by the purity, without which experience could do; however, an interesting problem is how and what the experience can do without it. Hence the idea that translation is based on a sort of negotiation, because they are such a basic process in which, in order to obtain something, abandon something else; and, ultimately, Contracting parties should emerge from this process with a sense of reasonable and mutual satisfaction, mindful of the Golden rule, according to which it is impossible to have it all.

Here one might ask, what are the Contracting parties in this negotiation process. A lot of them, even if sometimes they lack initiative: on the one hand, there is the source with their Autonomous rights, and sometimes the shape of the empirical the author (still alive) and his possible claims to control, as well as all the culture in which this text is born; on the other hand, there is the text of arrival and the culture in which it appears, with the system's expectations of his prospective readers, and sometimes even with the publishing industry, foreseeing the different criteria of translation in matter, which creates the text: for strict philological series or for a collection of entertaining books. The publisher may even require that the translated detective novel in Russian was removed diacritical marks are used when transferring character names to make it easier for readers to identify and remember them. The interpreter acts as the person conducting the negotiations between the actual or potential parties to such negotiations prior Express consent of the parties is not always expected.

However, some implicit negotiations take place in the covenants about accuracy, and they are different for readers who undertake the history books, and for those who read the novels: in force of the agreement, existing for thousands of years, the latter can provide a temporary exemption from the obligation to Express incredulity. published

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: theoryandpractice.ru