657

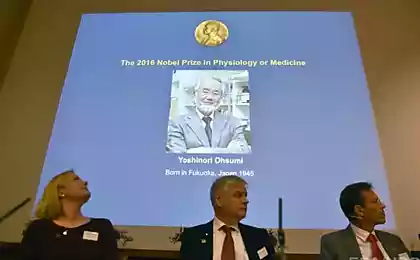

joseph brodsky. Nobel lecture

For the person private and particular this life a social role preferred, for a person who have come to this preference is quite far — and in particular from the homeland, for it is better to be the latest failure in democracy than a Martyr or a master of thoughts in despotism, — to appear suddenly on this platform — a big embarrassment and a challenge.

Forty million five hundred thirty five thousand two hundred fifty six

The feeling is compounded not so much by the thought of those who stood here before me, as the memory of those that honor had passed, who could not apply what is called "Urbi et Orbi" from this podium and whose total silence as it seeks and finds in you output.

The only thing that can reconcile you to such a position, is the simple consideration, that for reasons primarily stylistic-the writer can't speak for the writer — especially a poet for the poet; what if there had been at this podium Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Robert frost, Anna Akhmatova, Winston ODEN, they would not help speak for themselves, and perhaps also would feel uncomfortable.

The shadows disturb me constantly, they are disturbing me today. In any case, they do not encourage me to eloquence. In my better moments, I deem myself their sum total, though invariably inferior to any one of them individually. For it to be better than them on paper is impossible; it is impossible to be better than them in life, and it is their life, no matter how tragic and bitter they were, making me often — probably more often than I should — regret the passing of time. If the light exists — and to deny them the possibility of eternal life, and I'm not more able than to forget about their existence in this — if the light exists, they hope, will forgive me and quality what I am going to Express: in the end, not the behavior on the podium dignity of our profession is measured.

I have mentioned only five of those whose work and whose fate I care about, at least by the fact that, without them, I would as a person and as a writer would be worth little: in any case I would not be standing here today. Them, these shadow -better: light sources — lamps? stars'? — it was, of course, more than five, and all of them are doom to absolute dumbness. Their number is substantial in the life of any conscious man of letters; in my case it is doubled, thanks to the two cultures to which I am fated to belong. Does not facilitate business as well and the thought of his contemporaries and fellow writers in both cultures, poets and writers whose talent I value above its own and that, if they are on this podium, would have long since got down to business, because they have more to say to the world than I do.

So I would like some comments — perhaps discordant, inconsistent and may confuse you with its incoherence. However, the amount of time given to me to collect my thoughts, and my profession will protect me, I hope, at least in part from accusations of randomness. People in my profession rarely claims to systematic thinking; at worst, it claims system. But he is, as a rule, borrowed from environment, from the public device, from studying philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to achieve an even and constant purpose than the creative processes that use the process of writing. The poems in Akhmatova's words, indeed, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable.

II

If art teaches anything (to the artist, in the first place), it is particular human existence. Being the most ancient — and most literal form of private enterprise, it wittingly or unwittingly encourages in a person is his feeling of individuality, uniqueness, individually — transforming it from a social animal into a personality. Lot can be divided: bread, bed, belief, beloved — but not a poem, say, Rainer Maria Rilke.

Works of art, literature in particular and the poem in particular are turning to man tete-a-tete, entering with him into direct, without intermediaries, relationships.That's what I dislike art in General, literature especially, and poetry in particular, adherents of the common good, masters of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. Because there's art, where read the poem, they discover on the site of the expected agreement and consensus — indifference and discordant, on a place of determination to action is the lack of attention and disgust. In other words, in the toe, which the zealots of the common good and masters of the masses tend to operate, art enters a "point-to-point-comma-minus", transforming each toe in if not always attractive, but the human face.

Great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, characterized her as possessing an "uncommon visage". The acquisition of this uncommon expression is, apparently, the meaning of individual existence, because of this we are prepared mealsnot as it were, genetically. Regardless of whether the person is a writer or reader, the task is to live your own, not imposed or prescribed from the outside, even the most noble-looking life. Because each of us is only one, and we know how it all ends. It would be dosadno to spend this one chance at repeating a strange appearance, the experience of others, for a tautology — the more a shame that the heralds of historical necessity, at whose instigation the man on the tautology that is willing to accept, in the coffin with him will not lie and will not say thank you.

Language and, presumably, literature are things that are more ancient and inevitable, more durable than any form of social organization. Anger, irony or indifference, expressed by literature toward the state is essentially the reaction constant, or better to say endless, in relation to the provisional, limited. At least until the government allows itself to interfere in the Affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere in the Affairs of the state. Political system, form of social organization, as any system does, is, by definition, a form of past time is trying to impose itself on the present (and often future), and people whose profession is language, — the last who can afford to forget it. Real danger for a writer is not only the possibility (and often reality) of persecution by the state, as the opportunity to be mesmerized by his state, monstrous or undergoing changes for the better — but always temporary -outlines.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics-not to mention its aesthetics-are always "yesterday"; language, literature are always "today" and often — especially in the case of the Orthodoxy of one or another system — even "tomorrow". One of the merits of literature is that it helps people to clarify the time of its existence, to distinguish yourself in the crowd as the precursors, and the like, to avoid tautology, that is fate, otherwise known under the honorary title "victim of history".

Art in General and literature in particular, remarkable, and different from the life that is always running repeats.In everyday life you can tell the same anecdote three times and three times, prompting laughter, to be the soul of society. In the art this form of behavior is called "cliché". Art is a recoilless weapon, and its development is not determined by the individuality of the artist, but the dynamics and logic of the material, previous history of funds that require to find (or suggest) every time a qualitatively new aesthetic solution. With its own genealogy, dynamics, logic and future, art is not synonymous, but, at best, parallel stories, and the way his existence is creation every time a new aesthetic reality. That is why it is often found "ahead of progress", ahead of history, whose main instrument is not clarified whether the us Marx? — it is a cliche.

Today, extremely common with the claim that the writer, in particular a poet, should make use of in their works the language of the street, the language of the crowd. For all his apparent democratic and tangible and practical advantages for a writer, this assertion is absurd and is an attempt to subordinate art, in this case, literature, and history. Only if we decided that the "sapiens" should stop in its development, the literature should speak the language of the people. Otherwise, people should speak the language of literature. Every new aesthetic reality clarifies for a man's ethical reality. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; the concept of "good" and "bad" concepts are primarily aesthetic, anticipating the category of "good" and "evil". In ethics is not "everything is permitted" because the aesthetics are not "everything is permitted" because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger or, on the contrary, reaching out to him, rejects it or runs it, does so instinctively, making an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Aesthetic choice is always individual, and aesthetic experience is always the experience private. Every new aesthetic reality makes man, its perejivaesh, face even more private, and particular this taking sometimes the form of literary (or some other) taste, can in itself be, if not guarantee, then at least a form of defense against enslavement. For a man of taste, particularly literary, less susceptible to the refrains and the rhythmical incantations peculiar to any version of political demagogy. It's not so much that virtue is not a guarantee of a masterpiece, but in the fact that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist. The richer the aesthetic experience of the individual, the sounder his taste, the sharper his moral focus, the freer — though perhaps not happier.

In this rather applied than a Platonic sense that we should understand the words of Dostoevsky, that "beauty will save the world", or the saying of Matthew Arnold that "we will save the poetry".

The world will likely save will not succeed, but the individual is always possible.Aesthetic sense in man has developed very rapidly, because, not even fully realizing what he is and what he really needed, people usually instinctively knows that he does not like and that he is not satisfied. In the anthropological sense, again, man being is an aesthetic creature before he is an ethical. So art, in particular literature, not a by-product of our species ' development, but exactly the opposite. If what distinguishes us from other members of the animal Kingdom is speech, then literature, and specifically poetry, as the highest form of literature, represents, roughly speaking, our species goal.

I am far from the idea of compulsory training in prosody and composition; however, the division of people into intellectuals and all the rest seems to me unacceptable. Morally, the division is like the division of society into rich and poor; but, if the existence of social inequality is still conceivable some purely physical, material study, for intellectual inequality these are impossible. What-what, and in this sense, the equality guaranteed to us by nature. It is not about education but about the education of speech, the slightest imprecision in which may trigger the invasion of human life is about choice. The existence of literature implies the existence at the level of literature — and not only moral, but also lexically. If a piece of music still leaves man the choice between the passive role of listener and active performer, a work of literature — of art, in the words of Montale, hopelessly semantic — dooms him to a role performer.

In this role, person should appear, I think it would be more likely than any other. Moreover, it seems to me that this role is the result of population explosion and related to the increasing atomization of society, i.e. with increasing isolation of the individual becomes more and more inevitable. I don't think I know more about life than any man my age, but I think that the companion book is more reliable than a friend or lover. A novel or a poem is not a monologue but a conversation of the writer with the reader — conversation, I repeat, extremely private, excluding all others, if you will, mutually misanthropic. At the time of this conversation a writer is equal to reader, as well, and Vice versa, regardless of whether he is a great writer or not. Equality is the equality of consciousness, and it remains with you for life in the form of a memory, vague or distinct, and sooner or later, one way or inappropriate, determines the behavior of the individual. That's what I mean, speaking about the role of the artist, the more natural that a novel or poem is a product of mutual loneliness of the writer and the reader.

In the history of our species in the history of Homo sapiens, the book is an anthropological development, similar essentially to the invention of the wheel. Arisen in order to give us an idea not only about our origins, but about what "sapiens" is capable of this, the book is a means of moving in space experience with the speed of a turn of the page. Moving this in turn, as any movement, turns into a flight from the common denominator, from attempts to force the denominator of this line, not rising earlier above the waist, our heart, our mind, our imagination. The flight is the flight in the direction of "uncommon visage" in the direction of the numerator, in the direction of individual in the direction of particular. Regardless of whose image and likeness we are created, we are already five billion, and other future other than outlined art, the person does not have. In the opposite case, we expect the past — primarily political, with all its mass by the police charms.

In any case, a situation in which art in General and literature in particular is the heritage (the prerogative) of a minority appears to me unhealthy and dangerous.

I'm not calling for the replacement state library -although the thought of this many times I visited — but I have no doubt that we choose our rulers based on their reading experience and not the basis of their political programs on the ground there would be less grief.I think that the potential ruler of our destinies would have to ask is not primarily about how he imagines the course of foreign policy and how it relates to Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoevsky. If only one fact that the daily bread of literature is the human variety and ugliness, it, literature, proves to be a reliable antidote to any known and future — attempts total, a mass approach to solving the problems of human existence. As the system of moral, at least insurance, it is much more effective than one or the other belief system or philosophical doctrine.

Because there may not be laws protecting us from ourselves, no criminal code does not provide punishment for crimes against literature. And among these most serious crimes is not censorship, etc., not the legend books the fire. There is a crime more serious is the neglect of the books, not the reading. For that crime, a person pays with his whole life; if the offender is a nation, it pays with its history. Living in the country in which I live, I first was ready to believe that there is a balance between material well-being of man and his literary ignorance; this keeps you from me, however, the history of the country where I was born and raised. For reduced to causation at least to a crude formula, the Russian tragedy is precisely the tragedy of a society in which literature turned out to be the prerogative of the minority: the famous Russian intelligentsia.

I don't want to dwell on the subject, do not want to darken this evening with thoughts of the tens of millions of lives, ruined millions, for what happened in Russia in the first half of the twentieth century occurred prior to the introduction of automatic weapons — in the name of political doctrine, the failure of which already lies in the fact that it requires human sacrifice for its realization.

I can only say that not from experience, alas, but only theoretically, I believe that for a person, having read Dickens, to shoot his own kind in the name of any of the ideas more difficult than for a person who has never read Dickens.And I'm talking about reading Dickens, Stendhal, Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, Melville, etc., i.e. literature, not literacy, not about education. Competent, educated man could, or that political treatise reading, to kill their own kind and even experience the delight of persuasion. Lenin was literate, Stalin was literate, Hitler also; Mao Zedong, he even wrote poems; the list of their victims, however, far exceeds the list read.

However, before moving on to poetry, I would like to add that the Russian experience could reasonably be regarded as a warning if only because the social structure of the West in General is still similar to what existed in Russia until 1917. (This, incidentally, explains the popularity of Russian psychological novel of the nineteenth century in the West and the comparative failure of the modern Russian prose. The social relations prevailing in Russia in the XX century are represented, apparently, the reader is no less outlandish than the names of the characters, preventing him from identifying with them.) The number of political parties, for example, on the eve of the October revolution of 1917 in Russia there were certainly not less than exists today in the US or the UK. In other words, dispassionate might notice that in a certain sense the nineteenth century in the West is still ongoing. In Russia it was over; and if I say that it ended in tragedy, it is primarily because of the number of casualties, which resulted in the onset of social and historical change. This tragedy killed is not a hero — dies choir.

III

Although the person whose mother tongue is Russian to speak about political evil is as natural as digestion, I would like now to change the subject. The discourses about the obvious that they corrupt the mind of its ease, its easy to gain a sense of rightness. This is their temptation, similar in its nature to the temptation of a social reformer, begets this evil. The awareness of this temptation and repulsion from him, to a certain extent responsible for the fate of many of my contemporaries, not to mention the colleagues responsible for the literature, podeh feathers emerged. It, that literature was not a flight from history nor a muffling of memory, as it may seem from the outside. "How can one write music after Auschwitz?"asks Adorno, and people familiar with Russian history can repeat the same issue by changing the name of the camp to repeat it, perhaps with more even right, because the number of people perished in Stalin's camps, far exceeds the number of perished in German. "And how after Auschwitz can you eat lunch?"said it once that the American poet mark strand. The generation to which I belong, at least, was able to compose this music.

This generation — the generation born just when the crematoria of Auschwitz were working at full capacity, when Stalin was at the Zenith of the divine, the absolute, nature itself, seemed to be sanctioned by the authorities, appeared in the world, apparently, to continue what, theoretically, should be interrupted in those crematoria and in an unmarked mass graves of Stalin's archipelago. The fact that not all was lost, at least in Russia, is in no small measure a credit to my generation, and I'm proud of him belonging to no lesser extent than the fact that I'm standing here today. And the fact that I'm standing here today is recognition of the achievements of this generation to culture; Recalling Mandelstam, I would add, to world culture. Looking back, I can say that we started out on empty -or on frightening its emptiness and intuitively rather than consciously, we aspired precisely to the recreation of the effect of continuity of culture, to the restoration of its forms and tropes, toward filling its few surviving, and often totally compromised, forms, with our own new to us or seemed to be, up to date content.

There was probably another way of further deformation, the poetics of ruins and debris, minimalism, choked breath. If we refused, not because he seemed to us by semidramatic, or because we were extremely animated with the idea of preserving the hereditary nobility known forms of culture, is tantamount in our minds to forms of human dignity. We refused it, because the choice really wasn't ours, and the choice of culture — and this choice, again, was aesthetic, not moral. Of course, the man is more natural to talk about yourself not as an instrument of culture, but, on the contrary, as its Creator and custodian. But if I now claim the opposite, that it's not because there's a certain charm in the paraphrasing at the end of the twentieth century, the Dam of Lord Shaftesbury, Schelling, or NOVALIS, but because someone who, as the poet always knows that what in the vernacular is called the voice of a Muse, is, in fact, the dictate of language; what language is his tool and he tool of language to continue its existence. Language, however, even if you imagine it as a kind of animate creature (which would only be fair) — to the ethical choice is not capable of.

The man is writing a poem for various reasons: to win the heart of the beloved to Express their attitude to surrounding reality, whether it's landscape or the state, to capture the state of mind in which he is to leave — how he's thinking at this minute — mark on the ground. He resorts to this form — the poem — for reasons most likely unconsciously-mimetic: black vertical clot of words in the middle of a white sheet of paper, apparently, reminds man about his own position in the world, about the proportion of prostranstvakh his body. But regardless of the reasons, on which he takes up the pen and regardless of the effect produced by what emerges from his pen, on his audience, no matter how big or small it may be, is an immediate consequence of this enterprise is the sensation of coming in direct contact with the language, or rather the feeling of the immediate confluence with the dependence on it, from what it has expressed, written, performed.

This dependence is absolute, despotic; but it unshackles as well. For, while always older than the writer, language still possesses the colossal centrifugal energy imparted to it by its temporal potential — that is, all lying ahead of time. And this potential is determined not so much by the quantitative part of the nation that speaks it, although this, too, as the quality of the poem written in it. Suffice it to recall the authors of Greek or Roman antiquity, it is enough to recall Dante. Created today in Russian or English, for example, guarantees the existence of these languages over the next Millennium.

Poet, I repeat, is the means of existence of language.Or, as the great Auden, he is the one whom the language lives. Not me, these lines are writing, you will not, in their reading, but the language in which they were written and in which you read them will remain not only because the language is more durable than humans, but because it was better adapted to the mutation.

Writing a poem, however, writes it not because he hopes for posthumous fame, although often he hopes that his poem will survive, though not for long. Writing a poem writes it because the language prompts, or simply dictates, the next line.

Beginning of the poem, the poet usually does not know how it will end, and sometimes be very surprised at what happened, because often turns out better than he expected, often his thought goes further than he expects. This is the moment when the future of language interferes with their present.There are, as we know, three modes of cognition: analytical, intuitive and the method that was used by the biblical prophets, revelation. Difference of poetry from other forms of literature in that it uses all three (tending mostly to the second and third), because all three are given in the language; and sometimes with one word, one rhyme writing a poem could get where no one before him did not happen, and further, perhaps, than he himself would have wished. One who writes a poem writes it above all because verse — extraordinary accelerator of consciousness, of thinking, of comprehending the universe. Having experienced this acceleration once, a man no longer able to refuse to repeat the experience, he falls into dependency on this process, as fall into dependency on drugs or alcohol. People in similar language, I believe, and called a poet.published

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: syg.ma/@natasha-melnichenko/iosif-brodskii-nobielievskaia-liektsiia

Forty million five hundred thirty five thousand two hundred fifty six

The feeling is compounded not so much by the thought of those who stood here before me, as the memory of those that honor had passed, who could not apply what is called "Urbi et Orbi" from this podium and whose total silence as it seeks and finds in you output.

The only thing that can reconcile you to such a position, is the simple consideration, that for reasons primarily stylistic-the writer can't speak for the writer — especially a poet for the poet; what if there had been at this podium Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Robert frost, Anna Akhmatova, Winston ODEN, they would not help speak for themselves, and perhaps also would feel uncomfortable.

The shadows disturb me constantly, they are disturbing me today. In any case, they do not encourage me to eloquence. In my better moments, I deem myself their sum total, though invariably inferior to any one of them individually. For it to be better than them on paper is impossible; it is impossible to be better than them in life, and it is their life, no matter how tragic and bitter they were, making me often — probably more often than I should — regret the passing of time. If the light exists — and to deny them the possibility of eternal life, and I'm not more able than to forget about their existence in this — if the light exists, they hope, will forgive me and quality what I am going to Express: in the end, not the behavior on the podium dignity of our profession is measured.

I have mentioned only five of those whose work and whose fate I care about, at least by the fact that, without them, I would as a person and as a writer would be worth little: in any case I would not be standing here today. Them, these shadow -better: light sources — lamps? stars'? — it was, of course, more than five, and all of them are doom to absolute dumbness. Their number is substantial in the life of any conscious man of letters; in my case it is doubled, thanks to the two cultures to which I am fated to belong. Does not facilitate business as well and the thought of his contemporaries and fellow writers in both cultures, poets and writers whose talent I value above its own and that, if they are on this podium, would have long since got down to business, because they have more to say to the world than I do.

So I would like some comments — perhaps discordant, inconsistent and may confuse you with its incoherence. However, the amount of time given to me to collect my thoughts, and my profession will protect me, I hope, at least in part from accusations of randomness. People in my profession rarely claims to systematic thinking; at worst, it claims system. But he is, as a rule, borrowed from environment, from the public device, from studying philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to achieve an even and constant purpose than the creative processes that use the process of writing. The poems in Akhmatova's words, indeed, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable.

II

If art teaches anything (to the artist, in the first place), it is particular human existence. Being the most ancient — and most literal form of private enterprise, it wittingly or unwittingly encourages in a person is his feeling of individuality, uniqueness, individually — transforming it from a social animal into a personality. Lot can be divided: bread, bed, belief, beloved — but not a poem, say, Rainer Maria Rilke.

Works of art, literature in particular and the poem in particular are turning to man tete-a-tete, entering with him into direct, without intermediaries, relationships.That's what I dislike art in General, literature especially, and poetry in particular, adherents of the common good, masters of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. Because there's art, where read the poem, they discover on the site of the expected agreement and consensus — indifference and discordant, on a place of determination to action is the lack of attention and disgust. In other words, in the toe, which the zealots of the common good and masters of the masses tend to operate, art enters a "point-to-point-comma-minus", transforming each toe in if not always attractive, but the human face.

Great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, characterized her as possessing an "uncommon visage". The acquisition of this uncommon expression is, apparently, the meaning of individual existence, because of this we are prepared mealsnot as it were, genetically. Regardless of whether the person is a writer or reader, the task is to live your own, not imposed or prescribed from the outside, even the most noble-looking life. Because each of us is only one, and we know how it all ends. It would be dosadno to spend this one chance at repeating a strange appearance, the experience of others, for a tautology — the more a shame that the heralds of historical necessity, at whose instigation the man on the tautology that is willing to accept, in the coffin with him will not lie and will not say thank you.

Language and, presumably, literature are things that are more ancient and inevitable, more durable than any form of social organization. Anger, irony or indifference, expressed by literature toward the state is essentially the reaction constant, or better to say endless, in relation to the provisional, limited. At least until the government allows itself to interfere in the Affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere in the Affairs of the state. Political system, form of social organization, as any system does, is, by definition, a form of past time is trying to impose itself on the present (and often future), and people whose profession is language, — the last who can afford to forget it. Real danger for a writer is not only the possibility (and often reality) of persecution by the state, as the opportunity to be mesmerized by his state, monstrous or undergoing changes for the better — but always temporary -outlines.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics-not to mention its aesthetics-are always "yesterday"; language, literature are always "today" and often — especially in the case of the Orthodoxy of one or another system — even "tomorrow". One of the merits of literature is that it helps people to clarify the time of its existence, to distinguish yourself in the crowd as the precursors, and the like, to avoid tautology, that is fate, otherwise known under the honorary title "victim of history".

Art in General and literature in particular, remarkable, and different from the life that is always running repeats.In everyday life you can tell the same anecdote three times and three times, prompting laughter, to be the soul of society. In the art this form of behavior is called "cliché". Art is a recoilless weapon, and its development is not determined by the individuality of the artist, but the dynamics and logic of the material, previous history of funds that require to find (or suggest) every time a qualitatively new aesthetic solution. With its own genealogy, dynamics, logic and future, art is not synonymous, but, at best, parallel stories, and the way his existence is creation every time a new aesthetic reality. That is why it is often found "ahead of progress", ahead of history, whose main instrument is not clarified whether the us Marx? — it is a cliche.

Today, extremely common with the claim that the writer, in particular a poet, should make use of in their works the language of the street, the language of the crowd. For all his apparent democratic and tangible and practical advantages for a writer, this assertion is absurd and is an attempt to subordinate art, in this case, literature, and history. Only if we decided that the "sapiens" should stop in its development, the literature should speak the language of the people. Otherwise, people should speak the language of literature. Every new aesthetic reality clarifies for a man's ethical reality. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; the concept of "good" and "bad" concepts are primarily aesthetic, anticipating the category of "good" and "evil". In ethics is not "everything is permitted" because the aesthetics are not "everything is permitted" because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger or, on the contrary, reaching out to him, rejects it or runs it, does so instinctively, making an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Aesthetic choice is always individual, and aesthetic experience is always the experience private. Every new aesthetic reality makes man, its perejivaesh, face even more private, and particular this taking sometimes the form of literary (or some other) taste, can in itself be, if not guarantee, then at least a form of defense against enslavement. For a man of taste, particularly literary, less susceptible to the refrains and the rhythmical incantations peculiar to any version of political demagogy. It's not so much that virtue is not a guarantee of a masterpiece, but in the fact that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist. The richer the aesthetic experience of the individual, the sounder his taste, the sharper his moral focus, the freer — though perhaps not happier.

In this rather applied than a Platonic sense that we should understand the words of Dostoevsky, that "beauty will save the world", or the saying of Matthew Arnold that "we will save the poetry".

The world will likely save will not succeed, but the individual is always possible.Aesthetic sense in man has developed very rapidly, because, not even fully realizing what he is and what he really needed, people usually instinctively knows that he does not like and that he is not satisfied. In the anthropological sense, again, man being is an aesthetic creature before he is an ethical. So art, in particular literature, not a by-product of our species ' development, but exactly the opposite. If what distinguishes us from other members of the animal Kingdom is speech, then literature, and specifically poetry, as the highest form of literature, represents, roughly speaking, our species goal.

I am far from the idea of compulsory training in prosody and composition; however, the division of people into intellectuals and all the rest seems to me unacceptable. Morally, the division is like the division of society into rich and poor; but, if the existence of social inequality is still conceivable some purely physical, material study, for intellectual inequality these are impossible. What-what, and in this sense, the equality guaranteed to us by nature. It is not about education but about the education of speech, the slightest imprecision in which may trigger the invasion of human life is about choice. The existence of literature implies the existence at the level of literature — and not only moral, but also lexically. If a piece of music still leaves man the choice between the passive role of listener and active performer, a work of literature — of art, in the words of Montale, hopelessly semantic — dooms him to a role performer.

In this role, person should appear, I think it would be more likely than any other. Moreover, it seems to me that this role is the result of population explosion and related to the increasing atomization of society, i.e. with increasing isolation of the individual becomes more and more inevitable. I don't think I know more about life than any man my age, but I think that the companion book is more reliable than a friend or lover. A novel or a poem is not a monologue but a conversation of the writer with the reader — conversation, I repeat, extremely private, excluding all others, if you will, mutually misanthropic. At the time of this conversation a writer is equal to reader, as well, and Vice versa, regardless of whether he is a great writer or not. Equality is the equality of consciousness, and it remains with you for life in the form of a memory, vague or distinct, and sooner or later, one way or inappropriate, determines the behavior of the individual. That's what I mean, speaking about the role of the artist, the more natural that a novel or poem is a product of mutual loneliness of the writer and the reader.

In the history of our species in the history of Homo sapiens, the book is an anthropological development, similar essentially to the invention of the wheel. Arisen in order to give us an idea not only about our origins, but about what "sapiens" is capable of this, the book is a means of moving in space experience with the speed of a turn of the page. Moving this in turn, as any movement, turns into a flight from the common denominator, from attempts to force the denominator of this line, not rising earlier above the waist, our heart, our mind, our imagination. The flight is the flight in the direction of "uncommon visage" in the direction of the numerator, in the direction of individual in the direction of particular. Regardless of whose image and likeness we are created, we are already five billion, and other future other than outlined art, the person does not have. In the opposite case, we expect the past — primarily political, with all its mass by the police charms.

In any case, a situation in which art in General and literature in particular is the heritage (the prerogative) of a minority appears to me unhealthy and dangerous.

I'm not calling for the replacement state library -although the thought of this many times I visited — but I have no doubt that we choose our rulers based on their reading experience and not the basis of their political programs on the ground there would be less grief.I think that the potential ruler of our destinies would have to ask is not primarily about how he imagines the course of foreign policy and how it relates to Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoevsky. If only one fact that the daily bread of literature is the human variety and ugliness, it, literature, proves to be a reliable antidote to any known and future — attempts total, a mass approach to solving the problems of human existence. As the system of moral, at least insurance, it is much more effective than one or the other belief system or philosophical doctrine.

Because there may not be laws protecting us from ourselves, no criminal code does not provide punishment for crimes against literature. And among these most serious crimes is not censorship, etc., not the legend books the fire. There is a crime more serious is the neglect of the books, not the reading. For that crime, a person pays with his whole life; if the offender is a nation, it pays with its history. Living in the country in which I live, I first was ready to believe that there is a balance between material well-being of man and his literary ignorance; this keeps you from me, however, the history of the country where I was born and raised. For reduced to causation at least to a crude formula, the Russian tragedy is precisely the tragedy of a society in which literature turned out to be the prerogative of the minority: the famous Russian intelligentsia.

I don't want to dwell on the subject, do not want to darken this evening with thoughts of the tens of millions of lives, ruined millions, for what happened in Russia in the first half of the twentieth century occurred prior to the introduction of automatic weapons — in the name of political doctrine, the failure of which already lies in the fact that it requires human sacrifice for its realization.

I can only say that not from experience, alas, but only theoretically, I believe that for a person, having read Dickens, to shoot his own kind in the name of any of the ideas more difficult than for a person who has never read Dickens.And I'm talking about reading Dickens, Stendhal, Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, Melville, etc., i.e. literature, not literacy, not about education. Competent, educated man could, or that political treatise reading, to kill their own kind and even experience the delight of persuasion. Lenin was literate, Stalin was literate, Hitler also; Mao Zedong, he even wrote poems; the list of their victims, however, far exceeds the list read.

However, before moving on to poetry, I would like to add that the Russian experience could reasonably be regarded as a warning if only because the social structure of the West in General is still similar to what existed in Russia until 1917. (This, incidentally, explains the popularity of Russian psychological novel of the nineteenth century in the West and the comparative failure of the modern Russian prose. The social relations prevailing in Russia in the XX century are represented, apparently, the reader is no less outlandish than the names of the characters, preventing him from identifying with them.) The number of political parties, for example, on the eve of the October revolution of 1917 in Russia there were certainly not less than exists today in the US or the UK. In other words, dispassionate might notice that in a certain sense the nineteenth century in the West is still ongoing. In Russia it was over; and if I say that it ended in tragedy, it is primarily because of the number of casualties, which resulted in the onset of social and historical change. This tragedy killed is not a hero — dies choir.

III

Although the person whose mother tongue is Russian to speak about political evil is as natural as digestion, I would like now to change the subject. The discourses about the obvious that they corrupt the mind of its ease, its easy to gain a sense of rightness. This is their temptation, similar in its nature to the temptation of a social reformer, begets this evil. The awareness of this temptation and repulsion from him, to a certain extent responsible for the fate of many of my contemporaries, not to mention the colleagues responsible for the literature, podeh feathers emerged. It, that literature was not a flight from history nor a muffling of memory, as it may seem from the outside. "How can one write music after Auschwitz?"asks Adorno, and people familiar with Russian history can repeat the same issue by changing the name of the camp to repeat it, perhaps with more even right, because the number of people perished in Stalin's camps, far exceeds the number of perished in German. "And how after Auschwitz can you eat lunch?"said it once that the American poet mark strand. The generation to which I belong, at least, was able to compose this music.

This generation — the generation born just when the crematoria of Auschwitz were working at full capacity, when Stalin was at the Zenith of the divine, the absolute, nature itself, seemed to be sanctioned by the authorities, appeared in the world, apparently, to continue what, theoretically, should be interrupted in those crematoria and in an unmarked mass graves of Stalin's archipelago. The fact that not all was lost, at least in Russia, is in no small measure a credit to my generation, and I'm proud of him belonging to no lesser extent than the fact that I'm standing here today. And the fact that I'm standing here today is recognition of the achievements of this generation to culture; Recalling Mandelstam, I would add, to world culture. Looking back, I can say that we started out on empty -or on frightening its emptiness and intuitively rather than consciously, we aspired precisely to the recreation of the effect of continuity of culture, to the restoration of its forms and tropes, toward filling its few surviving, and often totally compromised, forms, with our own new to us or seemed to be, up to date content.

There was probably another way of further deformation, the poetics of ruins and debris, minimalism, choked breath. If we refused, not because he seemed to us by semidramatic, or because we were extremely animated with the idea of preserving the hereditary nobility known forms of culture, is tantamount in our minds to forms of human dignity. We refused it, because the choice really wasn't ours, and the choice of culture — and this choice, again, was aesthetic, not moral. Of course, the man is more natural to talk about yourself not as an instrument of culture, but, on the contrary, as its Creator and custodian. But if I now claim the opposite, that it's not because there's a certain charm in the paraphrasing at the end of the twentieth century, the Dam of Lord Shaftesbury, Schelling, or NOVALIS, but because someone who, as the poet always knows that what in the vernacular is called the voice of a Muse, is, in fact, the dictate of language; what language is his tool and he tool of language to continue its existence. Language, however, even if you imagine it as a kind of animate creature (which would only be fair) — to the ethical choice is not capable of.

The man is writing a poem for various reasons: to win the heart of the beloved to Express their attitude to surrounding reality, whether it's landscape or the state, to capture the state of mind in which he is to leave — how he's thinking at this minute — mark on the ground. He resorts to this form — the poem — for reasons most likely unconsciously-mimetic: black vertical clot of words in the middle of a white sheet of paper, apparently, reminds man about his own position in the world, about the proportion of prostranstvakh his body. But regardless of the reasons, on which he takes up the pen and regardless of the effect produced by what emerges from his pen, on his audience, no matter how big or small it may be, is an immediate consequence of this enterprise is the sensation of coming in direct contact with the language, or rather the feeling of the immediate confluence with the dependence on it, from what it has expressed, written, performed.

This dependence is absolute, despotic; but it unshackles as well. For, while always older than the writer, language still possesses the colossal centrifugal energy imparted to it by its temporal potential — that is, all lying ahead of time. And this potential is determined not so much by the quantitative part of the nation that speaks it, although this, too, as the quality of the poem written in it. Suffice it to recall the authors of Greek or Roman antiquity, it is enough to recall Dante. Created today in Russian or English, for example, guarantees the existence of these languages over the next Millennium.

Poet, I repeat, is the means of existence of language.Or, as the great Auden, he is the one whom the language lives. Not me, these lines are writing, you will not, in their reading, but the language in which they were written and in which you read them will remain not only because the language is more durable than humans, but because it was better adapted to the mutation.

Writing a poem, however, writes it not because he hopes for posthumous fame, although often he hopes that his poem will survive, though not for long. Writing a poem writes it because the language prompts, or simply dictates, the next line.

Beginning of the poem, the poet usually does not know how it will end, and sometimes be very surprised at what happened, because often turns out better than he expected, often his thought goes further than he expects. This is the moment when the future of language interferes with their present.There are, as we know, three modes of cognition: analytical, intuitive and the method that was used by the biblical prophets, revelation. Difference of poetry from other forms of literature in that it uses all three (tending mostly to the second and third), because all three are given in the language; and sometimes with one word, one rhyme writing a poem could get where no one before him did not happen, and further, perhaps, than he himself would have wished. One who writes a poem writes it above all because verse — extraordinary accelerator of consciousness, of thinking, of comprehending the universe. Having experienced this acceleration once, a man no longer able to refuse to repeat the experience, he falls into dependency on this process, as fall into dependency on drugs or alcohol. People in similar language, I believe, and called a poet.published

P. S. And remember, just changing your mind — together we change the world! ©

Source: syg.ma/@natasha-melnichenko/iosif-brodskii-nobielievskaia-liektsiia

The purslane: a unique nutritional and medicinal properties

Okinawa world's center of longevity: there are 319 centennial people