142

The Diligence Trap: What You Are Doing Wrong

After a grueling day at work, you sat down on the couch or sat down on the bar chair: in the end, you worked your hours, dealt with the to-do list, and made some effort. In such moments of satisfaction, you are entitled to some complacency, right? Oliver Berkman, a regular columnist on the psychology of The Guardian, thinks otherwise. Here’s his article explaining why it’s wrong to rely on fatigue to evaluate your performance.

I'm afraid I'll ruin this martini for you, but I will. We often confuse the feeling of effort with the actual results. For anyone working in the creative field, this mismatch carries the risk of wasting time and effort on imitating activities rather than on work that is actually taken into account.

Psychologists have long noticed a phenomenon known as the “illusion of work.” In assessing the work done by other people, we are likely to say that we are only interested in how quickly and well they did it. But in fact, we want to feel that they have done their best for us.

Behavioral economics expert Dan Ariely told the story of a locksmith who noticed this pattern: the better the quality of his work became, the less customers left for tea and the more often they complained about prices. Each task took so little time or effort that people seemed to be deceived, although it is obvious that high speed is an advantage of the locksmith, not a disadvantage.

In 2011, researchers Ryan Buell and Michael Norton of Harvard Business School found that users of the site preferred to wait longer for the final issue to search for air travel options - provided they could observe a detailed display of the progress of the unloading results on the monitor. This was perceived by them as a clear proof that the service “works hard” – combing the database of each airline.

Mason Kerry, in his 2013 book Daily Rituals, described the working modes of artists and writers. It turns out that almost none of them spend more than four to five hours a day on their own creative tasks.

This might just be a quirk of consumer behavior, were it not for the fact that we apply the same distorted standards to ourselves. Call it a “diligence trap”: it is menacingly easy to feel that the 10-hour workday you spent burying yourself in an email or sitting on your phone was worth more than the two hours spent in concentration or intense reflection, after which you devoted the rest of the day to leisure.

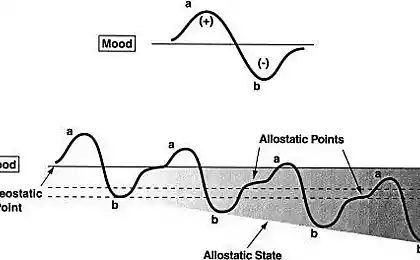

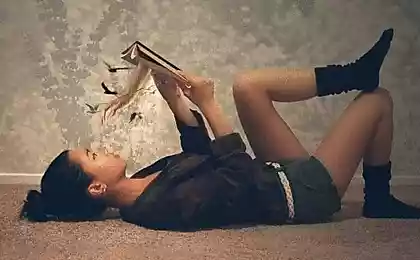

But any writer, designer, or web developer will tell you that the biggest payoff comes from those two hours of concentration, both in terms of profit and fulfillment. In fact, meaningful work does not always lead to exhaustion – on the contrary, a few hours of immersion in thought can cheer you up.

Avoiding the “diligence trap” is doubly difficult, because our culture is aggressively imposing on us the deceptive idea that, in the end, perseverance is all that matters.

Since childhood, parents and teachers hammer into our heads the idea of the benefits of diligence and the need to “do everything possible.” Many productivity-enhancing theories encourage a mindset that can be described as “do and strike off the list.” Practitioners of this approach are so busy clarifying their tasks and keeping records of their performance that they do not have time to wonder whether they are giving themselves the right tasks.

If you judge your performance by relying on fatigue, you may be mistaken. Too many employers continue to impose on their employees the idea that the best path to promotion is through effort, which usually translates into long hours. But in fact, if you do your job brilliantly and leave at 15:00 a.m. every day, a really good boss wouldn’t mind. By the same logic, you do not have to recall all the efforts made, arguing your request for a promotion.

Why should a result-focused boss care about your efforts? In America and Northern Europe, the zeal trap is probably rooted in Protestant work ethic, the old Calvinist idea that only those who work hard will go to heaven. Alas, to achieve a paradise of creativity, you need to practice a different approach - to prioritize the implementation of the necessary tasks, not their number.

The popular advice that the most important tasks should be done first is probably still the best. Thus, if you then immerse yourself in the “stormy activity”, you will still rationally spend your main energy resources.

If the work environment allows, try to radically reduce your working hours for the sake of the experiment: this limitation will allow you to allocate priorities more efficiently.

Throughout the day, you can set electronic reminders that will prompt you to switch to something else. And most importantly, remember that working to wear out or planning every minute is not a reliable indicator that the day was productive. Or, to put it more cheerfully, the path to creative self-actualization can take a lot less energy than you think. published

Author: Elena Kochetkova P.S. And remember, just by changing our consumption, we change the world together! © Join us on Facebook , VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: theoryandpractice.ru/posts/12715-work-hard

I'm afraid I'll ruin this martini for you, but I will. We often confuse the feeling of effort with the actual results. For anyone working in the creative field, this mismatch carries the risk of wasting time and effort on imitating activities rather than on work that is actually taken into account.

Psychologists have long noticed a phenomenon known as the “illusion of work.” In assessing the work done by other people, we are likely to say that we are only interested in how quickly and well they did it. But in fact, we want to feel that they have done their best for us.

Behavioral economics expert Dan Ariely told the story of a locksmith who noticed this pattern: the better the quality of his work became, the less customers left for tea and the more often they complained about prices. Each task took so little time or effort that people seemed to be deceived, although it is obvious that high speed is an advantage of the locksmith, not a disadvantage.

In 2011, researchers Ryan Buell and Michael Norton of Harvard Business School found that users of the site preferred to wait longer for the final issue to search for air travel options - provided they could observe a detailed display of the progress of the unloading results on the monitor. This was perceived by them as a clear proof that the service “works hard” – combing the database of each airline.

Mason Kerry, in his 2013 book Daily Rituals, described the working modes of artists and writers. It turns out that almost none of them spend more than four to five hours a day on their own creative tasks.

This might just be a quirk of consumer behavior, were it not for the fact that we apply the same distorted standards to ourselves. Call it a “diligence trap”: it is menacingly easy to feel that the 10-hour workday you spent burying yourself in an email or sitting on your phone was worth more than the two hours spent in concentration or intense reflection, after which you devoted the rest of the day to leisure.

But any writer, designer, or web developer will tell you that the biggest payoff comes from those two hours of concentration, both in terms of profit and fulfillment. In fact, meaningful work does not always lead to exhaustion – on the contrary, a few hours of immersion in thought can cheer you up.

Avoiding the “diligence trap” is doubly difficult, because our culture is aggressively imposing on us the deceptive idea that, in the end, perseverance is all that matters.

Since childhood, parents and teachers hammer into our heads the idea of the benefits of diligence and the need to “do everything possible.” Many productivity-enhancing theories encourage a mindset that can be described as “do and strike off the list.” Practitioners of this approach are so busy clarifying their tasks and keeping records of their performance that they do not have time to wonder whether they are giving themselves the right tasks.

If you judge your performance by relying on fatigue, you may be mistaken. Too many employers continue to impose on their employees the idea that the best path to promotion is through effort, which usually translates into long hours. But in fact, if you do your job brilliantly and leave at 15:00 a.m. every day, a really good boss wouldn’t mind. By the same logic, you do not have to recall all the efforts made, arguing your request for a promotion.

Why should a result-focused boss care about your efforts? In America and Northern Europe, the zeal trap is probably rooted in Protestant work ethic, the old Calvinist idea that only those who work hard will go to heaven. Alas, to achieve a paradise of creativity, you need to practice a different approach - to prioritize the implementation of the necessary tasks, not their number.

The popular advice that the most important tasks should be done first is probably still the best. Thus, if you then immerse yourself in the “stormy activity”, you will still rationally spend your main energy resources.

If the work environment allows, try to radically reduce your working hours for the sake of the experiment: this limitation will allow you to allocate priorities more efficiently.

Throughout the day, you can set electronic reminders that will prompt you to switch to something else. And most importantly, remember that working to wear out or planning every minute is not a reliable indicator that the day was productive. Or, to put it more cheerfully, the path to creative self-actualization can take a lot less energy than you think. published

Author: Elena Kochetkova P.S. And remember, just by changing our consumption, we change the world together! © Join us on Facebook , VKontakte, Odnoklassniki

Source: theoryandpractice.ru/posts/12715-work-hard