370

Components of success: innate, invented and acquired

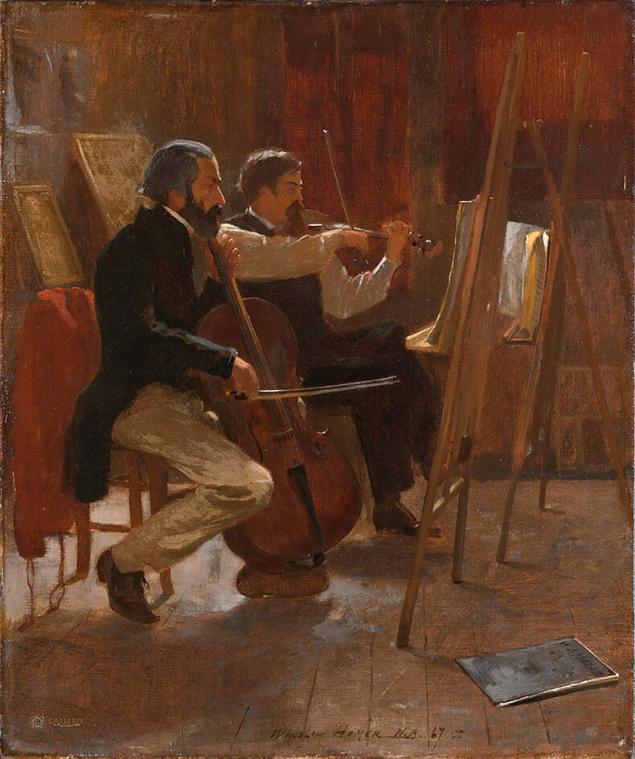

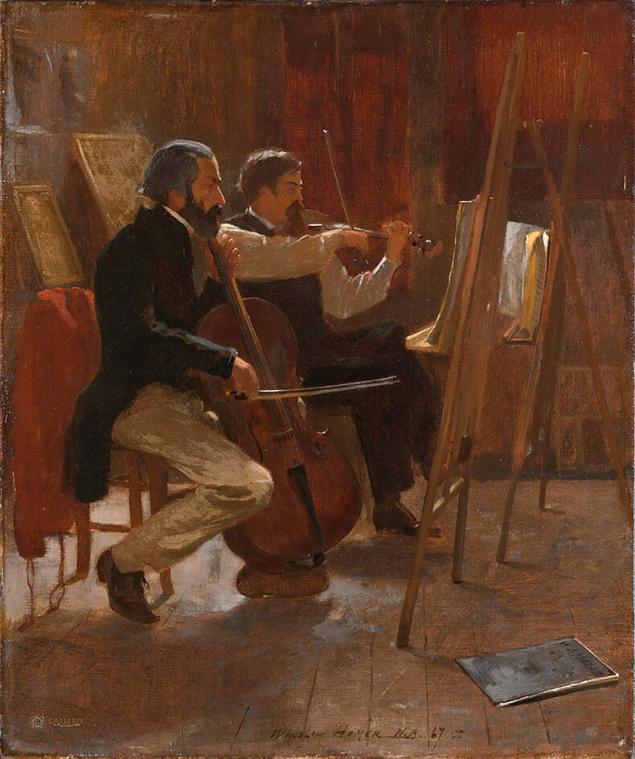

In 2000, Professor Gary McPherson of the University of Melbourne asked children between 7 and 9 years old who had just entered music school some interesting questions. He wanted to find out what factors influence successful music learning – what makes the right motivation?

The children were asked, “How long are you going to play the instrument you choose?” After just 9 months, there was a noticeable difference between the two: those who were going to change the instrument after a few years, or who didn’t take learning music seriously at all, performed worse, regardless of the time they devoted to their studies. The best performers were those who had strong expectations for music, who were generally more engaged and farther advanced than the rest.

The expectations and values children put into learning proved to be a better predictor of their success than any set of initial abilities or the number of hours spent in class.

The study was repeated after 3 years and again after 10 years. Much has changed, but the main results remain the same. Increased practice and innate abilities alone were not enough to explain the success of some and the failure of others.

To succeed not only in music, but in any other occupation, you need to make it part of your identity.

That’s not the only answer to what makes us successful. People have tried to answer it in many different ways. If we used to talk about the fate and blessing of the gods, now we are talking about talent, innate abilities, social environment or genetic predisposition. But even if you add up all these factors, it will not be enough to fully explain.

We will need to take a broader look at what we call talent if we do not want to squeeze the vast field of human skills and abilities into a Procrustean bed of narrow definitions.

Why we overestimate intelligence

One of the largest and longest-running studies of giftedness was launched in 1921 at Stanford University. Its creator and main ideologist Lewis Terman was born in 1877 in a large farm family in the eastern United States. Dr. B. R. Hegenhan, in his book Introduction to the History of Psychology, says that when Lewis was 9 years old, his family was visited by a phrenologist. Having felt the protrusions and curves on the boy’s skull, he predicted that Lewis would have a great future.

Terman became one of the most famous psychologists of the twentieth century and greatly influenced our perception of innate abilities and intelligence. Thanks to his efforts, we all know what IQ tests are. And sometimes we even give their results great importance.

Lewis Terman in his Stanford office.

Terman was their hot propagandist. There is nothing more important in a person than his IQ (except perhaps his moral values). It is the measure of intelligence that determines (according to Terman’s early beliefs) who will become the elite, the source of new ideas and positive transformation, and who will become a potential burden to the rest of society.

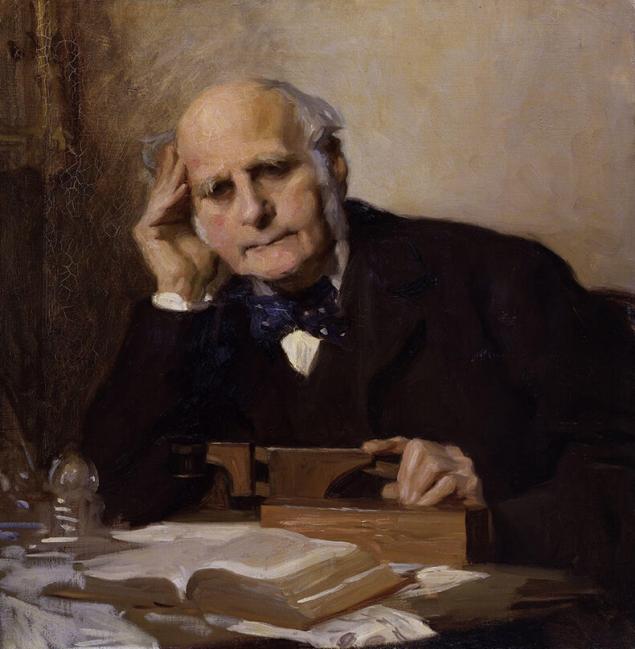

Terman was largely based on the ideas of Francis Galton, one of the founders of psychometrics. In 1883, Galton wrote a book, “Inquiry into human abilities and their development”, in which he explained the difference in human development by hereditary factors.

Intelligence in the understanding of Terman is the ability to abstract thinking, the ability to operate abstract concepts. To prove the importance of high intelligence with objective data, he collected more than 1,500 children across the United States with IQ scores above 135. From that moment his famous study of giftedness began. At first, Terman only wanted to replicate and expand on one of his earlier scientific projects, and in the end, the research took his whole life and even went beyond it.

People with high IQs were, on average, healthier, wealthier, more successful in school and work than their less intelligent counterparts. For a while, it seemed that IQ could indeed be described as a factor that determines outstanding achievement: by adulthood, Terman’s group had “produced thousands of scientific articles, 60 documentaries, 33 novels, 375 short stories, 230 patents, as well as numerous television and radio broadcasts, works of art and music.”

What were the results? For us, they may sound like a complete banality, but they brought Terman some serious surprises.

But he soon became disillusioned with his beliefs and found that intelligence, which can be measured by tests, was very weakly correlated with success. The life path of his wards was completely different. And none of the cohort of termites (as the participants in the study called themselves) could achieve anything truly remarkable.

The history of IQ testing in a sense repeated the fate of phrenology.

It is a more sophisticated but equally unsuccessful attempt to measure a complex and shaky entity like intelligence with a single set of predetermined attributes.

Terman’s approach to the definition of intelligence, which is still consciously or unconsciously reproduced in learning and educational practice, can be called substantial. More appealing today is his alternative, presented, for example, by Howard Gardner with his concept of “multiple intelligence,” which he first described in 1983 in The Structure of Mind.

According to his definition, intelligence is “the ability to solve problems or create products due to specific cultural characteristics or social environment.”

According to Gardner, intelligence is not some stable substance that can be measured in numbers; it is a quality that is inextricably linked to practice, the social environment, and its cultural characteristics.

Even if there are some innate qualities that determine intelligence, it is impossible to imagine them in isolation from upbringing and environment. The individual pygmies of the Mbuti tribe in the Republic of Congo are probably no dumber than an American middle-class official, but they were born and raised in so different conditions that even the most ardent admirers of psychometrics will hardly think of comparing their abilities and building hierarchies.

Talent cannot be discovered, but it can be invented.

High IQ alone cannot be the cause of outstanding achievement in life. This, in general, can not be proved by references to research, a few examples would suffice. Try to think of people with abnormally high IQ scores – you’re unlikely to be able to do that. They are good at solving problems, memorizing information, and sometimes learning languages, but they have not yet distinguished themselves by any special achievements.

What then determines success? The answer, which is deeply rooted in our mythology and culture, is that it's talent, genius, extraordinary ability, hidden somewhere in the back of our personality.

Talent, if genuine, is discovered in early childhood, and the rest of life becomes the road to its full disclosure and realization.

The earlier the talent shows up, the better.

In popular culture, talent is always marked by some sign, a magical halo: for example, a scar in the form of lightning.

At the junction of these representations, the image of the prodigy appears. In his classic book Mythologies, Roland Barth analyzed the image of Minu Drouet, a poet who became famous for her poems at the age of eight.

... before us is still an inexhaustible myth about genius. Classics once said that genius is patience. Today, however, genius consists in getting ahead of time, writing at eight what is normally written at twenty-five. It’s a quantitative question of time — you just have to evolve a little faster than others. Therefore, childhood is a privileged area of genius.

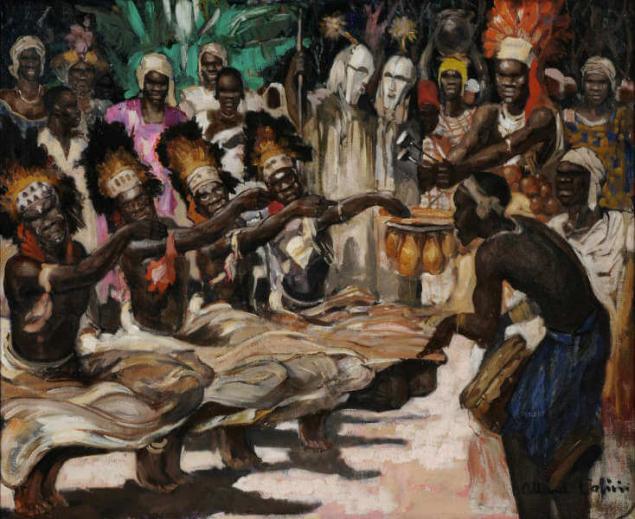

The word “talent” has magical connotations. In many cultures, witchcraft was considered an innate ability hidden from prying eyes. Here I would like to give another example - this time associated with the African people Azande, which is magnificently described by the British anthropologist Evans-Prichard.

Azanda believes that the power of magic is contained in a substance or organ that resides in the body of a sorcerer. This ability is inherited, but may not occur:

It can remain dormant, “cold,” as the azande put it, throughout his life, and a man can hardly be considered a sorcerer if his magical power has never functioned. Therefore, in the face of this fact, the azande tend to consider witchcraft as an individual feature, despite the fact that it is associated with blood kinship.

Talent (or what we mean by that word) is very similar. And like the magic of the azande, it exists only in our imaginations.

Ritual dances with masks in the Songue tribe (Republic of Congo). Fernand Allard l'Olivier.

Of course, no one is going to deny the presence of an innate predisposition to certain occupations. But in order for them to manifest themselves, a suitable environment and practice are needed. Conscious practice. And maybe at least 10 years of continuous work on yourself.

Mindful Practice: The Truth and Myth of 10,000 Hours

The concept of conscious practice was introduced into scientific circulation by the Swedish psychologist Anders Eriksson from the University of Florida. His first (and later famous) research was conducted in 1993 at the Berlin Academy of Music.

What distinguishes an outstanding musician from a mediocre one? The response of Eriksson and colleagues is practice, practice again, more practice. But it is not the number of hours that matters. There's something more important.

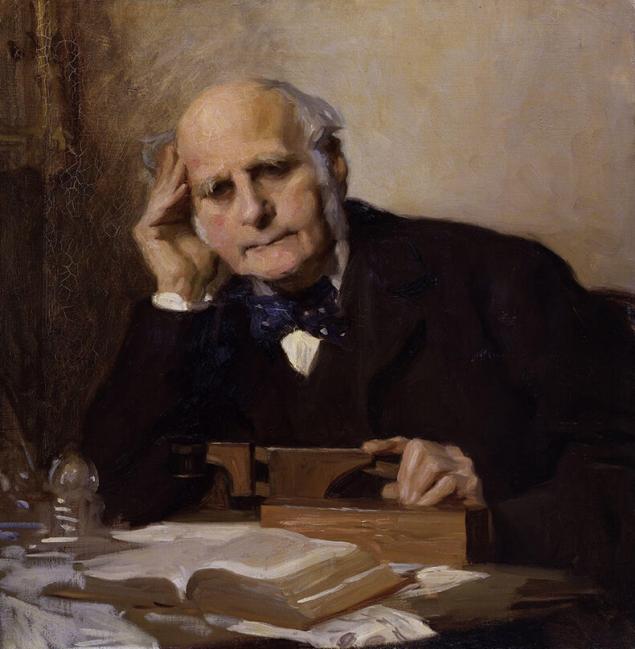

Francis Galton, whom we have already mentioned in connection with Terman’s research, in his book The Inheritance of Talent. Laws and Consequences, which he wrote in 1869, asserted that man can improve his skills and abilities only to a certain limit, which "cannot be overcome even by further education and improvement."

Francis Galton at work. Charles Wellington Furse, 1954.

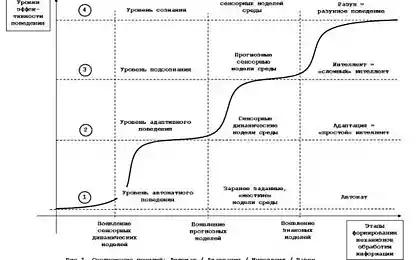

When we learn something, learn new skills, we go through several stages. At first, it is difficult: you have to learn a lot of new things, change familiar patterns of behavior, navigate the chaos of unfamiliar terms and definitions. Then we learn a set of rules that we can do more or less calmly and not worry about things going wrong. This is the Galton Wall. We bring our skills to automaticity and stop.

Ericsson showed that the best musicians were those who did not just do more, but did it consciously. The term “conscious practice” has 3 components: (a) focus on the technique, (b) focus on the goal and (c) get a stable and immediate response to their actions.

“Mechanical repetitions are useless,” Eriksson wrote, “there is a need to change the technique to get closer to the goal.”

But to achieve truly noticeable results, you need to constantly balance on the edge of your comfort zone.

For musicians, conscious practice will be playing the instrument alone with an emphasis on honing the technique and playing out the smallest details of each work; for writers – working with the word, the structure of the text, editing and editing the written “outline”, for teachers – something third, for doctors – the fourth, etc. It is important that this practice be meaningful.

Each skill should be broken down into many small parts and work with each of them, attentively listening to yourself and to the reaction to your actions.

Each skill should be broken down into many small parts and work with each of them, attentively listening to yourself and to the reaction to your actions.

For a journalist, for example, comments on his articles should become a necessary part of conscious practice. For the teacher - the reaction of the class; understanding, inspiration or confusion of each of the students.

Another takeaway from Ericsson’s work that has received much more attention is the so-called 10,000-hour rule.

In fact, this is just an average, which in itself means little. Malcolm Gladwell, who has the dubious merit of popularizing this “rule,” writes bluntly in his book Geniuses and Outsiders that 10,000 hours is “the magic number of the greatest skill.” He does not even mention conscious practice.

The 10,000-hour rule, circulated in the popular press and online, prompted a response from Eriksson: in 2012, he published a text entitled “Why it is dangerous to delegate education to journalists.” Practice is important, but there are no hours after which you will automatically become a world-class specialist. Duration of work is weakly correlated with success - and this applies to any occupation.

Practice, as well as innate abilities, is only one of the indicators that together affect the result.

The McPherson musicians we started with showed that success is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We achieve great results if we believe that it is important to us. To advance in any occupation, we need teachers who help us move out of our comfort zone, overcome automation, and consciously improve our skills.

Therefore, the main thing to learn is to perceive each failure not as a failure, but as an incentive to move on.

When teachers aren’t around, we’ll need meta-learning tools: knowing how to learn on your own so you don’t get stuck.

Success is ultimately a story we tell ourselves. How successful this story will turn out is determined not only by us. Just as a writer depends on the language in which he writes, so each of us depends on the environment. But the plot and style of the story still remains on the conscience of the writer. published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

You might be interested.

Brian Tracy: Start your day right

10 random decisions that led to non-random victories

Source: newtonew.com/discussions/what-makes-a-success

The children were asked, “How long are you going to play the instrument you choose?” After just 9 months, there was a noticeable difference between the two: those who were going to change the instrument after a few years, or who didn’t take learning music seriously at all, performed worse, regardless of the time they devoted to their studies. The best performers were those who had strong expectations for music, who were generally more engaged and farther advanced than the rest.

The expectations and values children put into learning proved to be a better predictor of their success than any set of initial abilities or the number of hours spent in class.

The study was repeated after 3 years and again after 10 years. Much has changed, but the main results remain the same. Increased practice and innate abilities alone were not enough to explain the success of some and the failure of others.

To succeed not only in music, but in any other occupation, you need to make it part of your identity.

That’s not the only answer to what makes us successful. People have tried to answer it in many different ways. If we used to talk about the fate and blessing of the gods, now we are talking about talent, innate abilities, social environment or genetic predisposition. But even if you add up all these factors, it will not be enough to fully explain.

We will need to take a broader look at what we call talent if we do not want to squeeze the vast field of human skills and abilities into a Procrustean bed of narrow definitions.

Why we overestimate intelligence

One of the largest and longest-running studies of giftedness was launched in 1921 at Stanford University. Its creator and main ideologist Lewis Terman was born in 1877 in a large farm family in the eastern United States. Dr. B. R. Hegenhan, in his book Introduction to the History of Psychology, says that when Lewis was 9 years old, his family was visited by a phrenologist. Having felt the protrusions and curves on the boy’s skull, he predicted that Lewis would have a great future.

Terman became one of the most famous psychologists of the twentieth century and greatly influenced our perception of innate abilities and intelligence. Thanks to his efforts, we all know what IQ tests are. And sometimes we even give their results great importance.

Lewis Terman in his Stanford office.

Terman was their hot propagandist. There is nothing more important in a person than his IQ (except perhaps his moral values). It is the measure of intelligence that determines (according to Terman’s early beliefs) who will become the elite, the source of new ideas and positive transformation, and who will become a potential burden to the rest of society.

Terman was largely based on the ideas of Francis Galton, one of the founders of psychometrics. In 1883, Galton wrote a book, “Inquiry into human abilities and their development”, in which he explained the difference in human development by hereditary factors.

Intelligence in the understanding of Terman is the ability to abstract thinking, the ability to operate abstract concepts. To prove the importance of high intelligence with objective data, he collected more than 1,500 children across the United States with IQ scores above 135. From that moment his famous study of giftedness began. At first, Terman only wanted to replicate and expand on one of his earlier scientific projects, and in the end, the research took his whole life and even went beyond it.

People with high IQs were, on average, healthier, wealthier, more successful in school and work than their less intelligent counterparts. For a while, it seemed that IQ could indeed be described as a factor that determines outstanding achievement: by adulthood, Terman’s group had “produced thousands of scientific articles, 60 documentaries, 33 novels, 375 short stories, 230 patents, as well as numerous television and radio broadcasts, works of art and music.”

What were the results? For us, they may sound like a complete banality, but they brought Terman some serious surprises.

But he soon became disillusioned with his beliefs and found that intelligence, which can be measured by tests, was very weakly correlated with success. The life path of his wards was completely different. And none of the cohort of termites (as the participants in the study called themselves) could achieve anything truly remarkable.

The history of IQ testing in a sense repeated the fate of phrenology.

It is a more sophisticated but equally unsuccessful attempt to measure a complex and shaky entity like intelligence with a single set of predetermined attributes.

Terman’s approach to the definition of intelligence, which is still consciously or unconsciously reproduced in learning and educational practice, can be called substantial. More appealing today is his alternative, presented, for example, by Howard Gardner with his concept of “multiple intelligence,” which he first described in 1983 in The Structure of Mind.

According to his definition, intelligence is “the ability to solve problems or create products due to specific cultural characteristics or social environment.”

According to Gardner, intelligence is not some stable substance that can be measured in numbers; it is a quality that is inextricably linked to practice, the social environment, and its cultural characteristics.

Even if there are some innate qualities that determine intelligence, it is impossible to imagine them in isolation from upbringing and environment. The individual pygmies of the Mbuti tribe in the Republic of Congo are probably no dumber than an American middle-class official, but they were born and raised in so different conditions that even the most ardent admirers of psychometrics will hardly think of comparing their abilities and building hierarchies.

Talent cannot be discovered, but it can be invented.

High IQ alone cannot be the cause of outstanding achievement in life. This, in general, can not be proved by references to research, a few examples would suffice. Try to think of people with abnormally high IQ scores – you’re unlikely to be able to do that. They are good at solving problems, memorizing information, and sometimes learning languages, but they have not yet distinguished themselves by any special achievements.

What then determines success? The answer, which is deeply rooted in our mythology and culture, is that it's talent, genius, extraordinary ability, hidden somewhere in the back of our personality.

Talent, if genuine, is discovered in early childhood, and the rest of life becomes the road to its full disclosure and realization.

The earlier the talent shows up, the better.

In popular culture, talent is always marked by some sign, a magical halo: for example, a scar in the form of lightning.

At the junction of these representations, the image of the prodigy appears. In his classic book Mythologies, Roland Barth analyzed the image of Minu Drouet, a poet who became famous for her poems at the age of eight.

... before us is still an inexhaustible myth about genius. Classics once said that genius is patience. Today, however, genius consists in getting ahead of time, writing at eight what is normally written at twenty-five. It’s a quantitative question of time — you just have to evolve a little faster than others. Therefore, childhood is a privileged area of genius.

The word “talent” has magical connotations. In many cultures, witchcraft was considered an innate ability hidden from prying eyes. Here I would like to give another example - this time associated with the African people Azande, which is magnificently described by the British anthropologist Evans-Prichard.

Azanda believes that the power of magic is contained in a substance or organ that resides in the body of a sorcerer. This ability is inherited, but may not occur:

It can remain dormant, “cold,” as the azande put it, throughout his life, and a man can hardly be considered a sorcerer if his magical power has never functioned. Therefore, in the face of this fact, the azande tend to consider witchcraft as an individual feature, despite the fact that it is associated with blood kinship.

Talent (or what we mean by that word) is very similar. And like the magic of the azande, it exists only in our imaginations.

Ritual dances with masks in the Songue tribe (Republic of Congo). Fernand Allard l'Olivier.

Of course, no one is going to deny the presence of an innate predisposition to certain occupations. But in order for them to manifest themselves, a suitable environment and practice are needed. Conscious practice. And maybe at least 10 years of continuous work on yourself.

Mindful Practice: The Truth and Myth of 10,000 Hours

The concept of conscious practice was introduced into scientific circulation by the Swedish psychologist Anders Eriksson from the University of Florida. His first (and later famous) research was conducted in 1993 at the Berlin Academy of Music.

What distinguishes an outstanding musician from a mediocre one? The response of Eriksson and colleagues is practice, practice again, more practice. But it is not the number of hours that matters. There's something more important.

Francis Galton, whom we have already mentioned in connection with Terman’s research, in his book The Inheritance of Talent. Laws and Consequences, which he wrote in 1869, asserted that man can improve his skills and abilities only to a certain limit, which "cannot be overcome even by further education and improvement."

Francis Galton at work. Charles Wellington Furse, 1954.

When we learn something, learn new skills, we go through several stages. At first, it is difficult: you have to learn a lot of new things, change familiar patterns of behavior, navigate the chaos of unfamiliar terms and definitions. Then we learn a set of rules that we can do more or less calmly and not worry about things going wrong. This is the Galton Wall. We bring our skills to automaticity and stop.

Ericsson showed that the best musicians were those who did not just do more, but did it consciously. The term “conscious practice” has 3 components: (a) focus on the technique, (b) focus on the goal and (c) get a stable and immediate response to their actions.

“Mechanical repetitions are useless,” Eriksson wrote, “there is a need to change the technique to get closer to the goal.”

But to achieve truly noticeable results, you need to constantly balance on the edge of your comfort zone.

For musicians, conscious practice will be playing the instrument alone with an emphasis on honing the technique and playing out the smallest details of each work; for writers – working with the word, the structure of the text, editing and editing the written “outline”, for teachers – something third, for doctors – the fourth, etc. It is important that this practice be meaningful.

Each skill should be broken down into many small parts and work with each of them, attentively listening to yourself and to the reaction to your actions.

Each skill should be broken down into many small parts and work with each of them, attentively listening to yourself and to the reaction to your actions.

For a journalist, for example, comments on his articles should become a necessary part of conscious practice. For the teacher - the reaction of the class; understanding, inspiration or confusion of each of the students.

Another takeaway from Ericsson’s work that has received much more attention is the so-called 10,000-hour rule.

In fact, this is just an average, which in itself means little. Malcolm Gladwell, who has the dubious merit of popularizing this “rule,” writes bluntly in his book Geniuses and Outsiders that 10,000 hours is “the magic number of the greatest skill.” He does not even mention conscious practice.

The 10,000-hour rule, circulated in the popular press and online, prompted a response from Eriksson: in 2012, he published a text entitled “Why it is dangerous to delegate education to journalists.” Practice is important, but there are no hours after which you will automatically become a world-class specialist. Duration of work is weakly correlated with success - and this applies to any occupation.

Practice, as well as innate abilities, is only one of the indicators that together affect the result.

The McPherson musicians we started with showed that success is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We achieve great results if we believe that it is important to us. To advance in any occupation, we need teachers who help us move out of our comfort zone, overcome automation, and consciously improve our skills.

Therefore, the main thing to learn is to perceive each failure not as a failure, but as an incentive to move on.

When teachers aren’t around, we’ll need meta-learning tools: knowing how to learn on your own so you don’t get stuck.

Success is ultimately a story we tell ourselves. How successful this story will turn out is determined not only by us. Just as a writer depends on the language in which he writes, so each of us depends on the environment. But the plot and style of the story still remains on the conscience of the writer. published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

You might be interested.

Brian Tracy: Start your day right

10 random decisions that led to non-random victories

Source: newtonew.com/discussions/what-makes-a-success

Without tablet and computer: game for kids 4-6 years

15 super ideas for a summer kitchen in the country