267

The paradox of solutions: Why We Make Stupid Decisions After Long Thinking

How much time you spend analyzing the situation and finding a solution is not a guarantee of success.

Imagine this situation: you are sitting in front of a computer for the third hour, analyzing all possible solutions to an important problem. You have compiled lists of pros and cons, studied statistics, consulted with experts. And you end up making a decision that turns out to be catastrophically wrong a week later. Familiar? Welcome to the world of decision-making paradox, where more time to think is not equal to better results.

A Harvard Business School study found that people who made intuitive decisions in 30 seconds were 73% more satisfied with the outcome than those who spent more than an hour on analysis.

Anatomy of Analytical Paralysis

When too much analysis leads to bad decisions, psychologists call analytical paralysis or the paradox of choice. Barry Schwartz, in his famous book The Paradox of Choice, proved that increasing the number of options does not make us happier, but rather paralyzes the ability to make effective choices.

Our brains have evolved to make quick decisions in critical situations. When a saber-toothed tiger runs at you, you don’t have time to make decision tables. But in today's world, we apply this rapid-response system to complex problems that require analysis, while at the same time trying to analyze simple questions that are better solved intuitively.

Why More Information Means Worst Decisions

Information overload

When we are faced with an excess of information, our brain begins to work like an overloaded processor. Each new fact creates additional connections and opportunities for analysis, but at the same time reduces the quality of processing of each individual element.

Researchers from Stanford found that people who were offered a choice of 24 types of jam bought 10 times less than those who were offered only 6 options. At the same time, those who still made a purchase from a large range were more likely to regret the choice made.

The anchoring effect and cognitive distortions

The longer we think, the more we experience cognitive distortion. The first information we receive (the anchoring effect) begins to dictate the direction of all subsequent analysis. We unknowingly search for facts to support our initial impression, ignoring conflicting data.

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel laureate in economics, explains in Think Slow... Decide Fast that our system of analytical thinking (System 2) gets tired easily and begins to delegate decisions to an intuitive system (System 1), but at the same time creates the illusion of careful analysis.

The Neurobiology of Rethinking

Modern studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging show that with prolonged deliberation, activity in the prefrontal cortex (responsible for rational thinking) gradually decreases, and activity in the limbic system (emotional brain) increases. This means that by thinking that we are becoming more rational, we are actually becoming more emotional.

The paradox is that the more we think about a solution, the less we actually think. The brain begins to work in the “autopilot” mode, creating the illusion of deep analysis.

Real-life stories

Steve Jobs was known for his quick, intuitive decisions. When the iPhone team spent months arguing about what material to use for the screen, Jobs chose glass in five minutes just by holding samples in his hands. This choice was revolutionary for the entire industry.

The opposite example is Blackberry. Management has spent years analyzing the smartphone market, studying competitors, and planning strategy. The result is that they completely missed the touchscreen revolution and lost the lead.

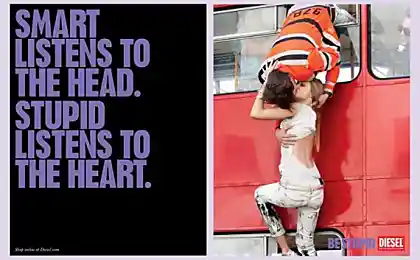

“The best decisions are often made not with the head but with the heart. Intuition is millions of years of evolution compressed at one moment of understanding. ?

Practical strategies for effective decision-making

Method 10-10-10

Ask yourself: How will I feel about this decision in 10 minutes, 10 months and 10 years? This method helps to weed out emotional reactions and focus on long-term consequences.

Two-list rule

Make two lists: “What I know exactly” and “What I assume.” It often turns out that there are many more items in the second list, and this helps to make a decision based on facts rather than speculation.

The reverse thinking technique

Imagine that you have already made every possible decision and it has failed. What were the reasons for the failure? This will help identify the hidden risks and weaknesses of each option.

Set time limits for making decisions. For everyday decisions – no more than 5 minutes, for important personal decisions – no more than an hour, for critical business decisions – no more than a week.

When to Trust Intuition

Research shows that intuition is especially effective in areas where you have a lot of experience. Doctors with many years of experience often make correct diagnoses on a whim because their subconscious processes thousands of previously seen cases.

Intuition works best in the following situations:

When you have significant experience in the field

When choosing between emotionally colored options (partner, residence, career)

Under temporary pressure conditions

When too much analysis can lead to decision paralysis

Technology of fast solutions

Amazon uses the principle of “one way, two ways.” Decisions of one path (irreversible) require careful analysis, and decisions of two paths (reversible) are made quickly. Jeff Bezos argued that most decisions fall into the second category, but people treat them as the first.

Before you start analyzing any problem, ask yourself, “Is this the solution of one path or two paths?” If it can be canceled or adjusted, take it quickly and adjust as you go.

Conclusion: The Art of Quick Decisions

The paradox of the modern world is that we have access to vast amounts of information, but that doesn't make our solutions any better. Conversely, information overload often leads to analytical paralysis and poor choices.

The key to effective decision-making lies not in the amount of information analyzed, but in the ability to determine what type of decision is in front of you and choose the appropriate strategy. Sometimes the best decision is the one made quickly, based on experience and intuition.

Remember, there is no perfect solution. A good decision made on time is always better than a perfect decision made too late.

Glossary

Analytical paralysis A state in which an excess of analysis and information leads to an inability to make a decision or an ineffective decision.

The paradox of choice A psychological phenomenon in which an increase in the number of choices reduces satisfaction from a decision.

The anchoring effect Cognitive distortion, in which the first information received (anchor) overly influences subsequent judgments and decisions.

System 1 and System 2 Daniel Kahneman’s concept describes two modes of thinking: fast intuitive (System 1) and slow analytical (System 2).

Prefrontal cortex The area of the brain responsible for executive function, planning, decision-making and impulse control.

limbic system A group of brain structures responsible for emotions, motivation, memory and behavioral responses.

Cognitive distortions Systematic errors in thinking that affect decision-making and judgment.

10 Common Psychological Masks and What Feelings We Hide Behind Them

How to see the essence of people. When a person kicks out a trait, it means he hides the opposite from you.