443

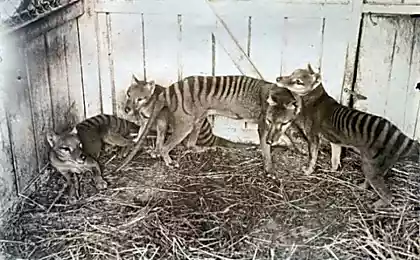

Man again accused in the extermination of the mammoths

Time the extinction of mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths coincides with the time of occurrence in their area of the person, says researcher Chris Sand.

In the disappearance of mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths, to blame people, says Chris Sands (Chris Sandom), co-founder of Wild Business Ltd., recently completed his doctoral thesis at Aarhus University (Denmark). A study published in the June issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Currently, there are three hypotheses about why at the end of the Pleistocene, about 12 thousand years ago, many extinct large mammals (they lived on all continents except Antarctica). According to one version, in large fauna destroyed by the people, on the other – these animals became extinct because of climate change. Some researchers believe that mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths became extinct due to some catastrophe, perhaps because of a meteorite.

The latter hypothesis has less likely reason: while we have no direct evidence of any major catastrophe that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene. Proponents of the theory that mammoths wiped out the man, point to the so-called kill-sites – places of the slaughter and butchering of animals, including extinct. Such monuments are known in different regions of the world. However, adherents of the "climate" version say that the slaughter is too small to say that man played a decisive role in the extermination of large mammals.

A group of researchers led by Chris Sangamam analyzed a large amount of information from different regions of the world. They compared the time of the disappearance of 177 mammals (considered only animals, reconstructed, and whose weight exceeded 10 kg) over time, the appearance of man in their habitats, as well as information about climate change. The study covered the time period between 132 thousand years ago (last interglacial) and 1 thousand years ago. Archaeologists and paleontologists have considered the information received not only in the scale of individual continents, but within individual countries as well as in cases when it had considered the territory of big States within small regions (e.g. States in the USA).

The analysis of this voluminous information allowed the authors to conclude that the disappearance of large mammals is more closely correlated with human migration than climate change. "Facts really give a good reason to assume that people were the defining factor," says Chris Sands.

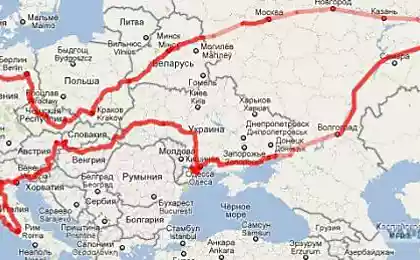

The small scale and the rate of extinction of animals recorded by archaeologists and paleontologists in Tropical Africa (sub-Saharan Africa, that is part of the continent South of the Sahara). The next region on these parameters – Eurasia. In America and in Australia, the extermination of large mammals was the most intense.

This corresponds to the hypothesis on the decisive role of human factor in the disappearance of mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths, says Chris Sands. Large animals in Tropical Africa lived in the same neighborhood with the people and their ancestors for a long time. Mammals of these regions were familiar with the methods of ancient hunters. When people outside of Africa, they began to hunt animals, to which such treatment was not used. Therefore, the rate and magnitude of species extinction in America and Australia are the biggest – part of the world these people inhabited later than other.

Strong relationship between animal extinction and climate change, the researchers found. Climate change could have on the process of indirect influence – they determined the migration paths of a person.

Climate change, of course, have a strong effect on animals. But climate variations are not always sentence – animals may modify or restrict the habitat to find habitat that will allow them to survive. Probably people dropped this adaptation process, says Chris Sands. "That was the last straw. They didn't know how to cope with the emergence of a new predator," concludes the researcher.

Source: nkj.ru

In the disappearance of mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths, to blame people, says Chris Sands (Chris Sandom), co-founder of Wild Business Ltd., recently completed his doctoral thesis at Aarhus University (Denmark). A study published in the June issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Currently, there are three hypotheses about why at the end of the Pleistocene, about 12 thousand years ago, many extinct large mammals (they lived on all continents except Antarctica). According to one version, in large fauna destroyed by the people, on the other – these animals became extinct because of climate change. Some researchers believe that mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths became extinct due to some catastrophe, perhaps because of a meteorite.

The latter hypothesis has less likely reason: while we have no direct evidence of any major catastrophe that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene. Proponents of the theory that mammoths wiped out the man, point to the so-called kill-sites – places of the slaughter and butchering of animals, including extinct. Such monuments are known in different regions of the world. However, adherents of the "climate" version say that the slaughter is too small to say that man played a decisive role in the extermination of large mammals.

A group of researchers led by Chris Sangamam analyzed a large amount of information from different regions of the world. They compared the time of the disappearance of 177 mammals (considered only animals, reconstructed, and whose weight exceeded 10 kg) over time, the appearance of man in their habitats, as well as information about climate change. The study covered the time period between 132 thousand years ago (last interglacial) and 1 thousand years ago. Archaeologists and paleontologists have considered the information received not only in the scale of individual continents, but within individual countries as well as in cases when it had considered the territory of big States within small regions (e.g. States in the USA).

The analysis of this voluminous information allowed the authors to conclude that the disappearance of large mammals is more closely correlated with human migration than climate change. "Facts really give a good reason to assume that people were the defining factor," says Chris Sands.

The small scale and the rate of extinction of animals recorded by archaeologists and paleontologists in Tropical Africa (sub-Saharan Africa, that is part of the continent South of the Sahara). The next region on these parameters – Eurasia. In America and in Australia, the extermination of large mammals was the most intense.

This corresponds to the hypothesis on the decisive role of human factor in the disappearance of mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths, says Chris Sands. Large animals in Tropical Africa lived in the same neighborhood with the people and their ancestors for a long time. Mammals of these regions were familiar with the methods of ancient hunters. When people outside of Africa, they began to hunt animals, to which such treatment was not used. Therefore, the rate and magnitude of species extinction in America and Australia are the biggest – part of the world these people inhabited later than other.

Strong relationship between animal extinction and climate change, the researchers found. Climate change could have on the process of indirect influence – they determined the migration paths of a person.

Climate change, of course, have a strong effect on animals. But climate variations are not always sentence – animals may modify or restrict the habitat to find habitat that will allow them to survive. Probably people dropped this adaptation process, says Chris Sands. "That was the last straw. They didn't know how to cope with the emergence of a new predator," concludes the researcher.

Source: nkj.ru

Set a world record in creating the solar supercritical steam

10 facts about the benefits and harms of chewing gum