266

The mystery of the Tarim mummies

Tarim mummies are an incomprehensible mystery of the ancient world and one of the most important archaeological finds of the XX century. These surprisingly well-preserved human remains were discovered in the arid salt sands of the Takla Makan Desert, which is part of the Tarim Basin in western China.

Discovered in those distant parts of the body dated a long time: 1800 BC – 400 AD. However, what struck scientists most was that the mummies had features of the Caucasian race. Apparently, in Western China lived tribes that mysteriously disappeared 2000 years ago.

The discoverer of mummies – Swedish scientist Sven Hedin in the early XX century. was engaged in the general history of the Silk Road – a network of ancient roads that once led from China to Turkey and further to Europe. The bodies were taken to European museums for further study, but the lack of equipment and funding meant they were soon forgotten.

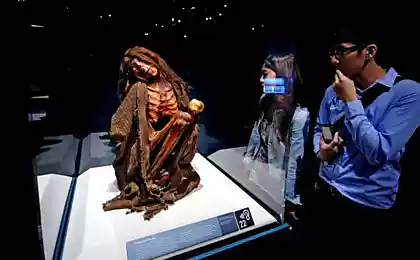

In 1978, Chinese archaeologist Wang Binghua discovered 113 mummified bodies in the Kizilchok burial ground, or Red Hill, in northeastern central Asian province of Xinyang. Most of the bodies were later transported to the Urumki Museum. Over the past 25 years, Chinese and Central Asian archaeologists have excavated and carried out extensive research in the area, uncovering more than 300 mummies.

In 1987, Victor Mair, a professor of Chinese and Indo-Iranian literature and religion at the University of Pennsylvania, led a group of tourists around the Urumka Museum and, approaching the mummies found by Wang Binghua, was surprised to find that they were all dressed in dark purple woollen clothing and felt shoes and had signs of a Caucasian race: brown or blond hair, elongated noses and skulls, slim bodies and large deep-set eyes.

The political situation in China at the time prevented Mayr from investigating these amazing finds, and in 1993 he returned with a group of Italian geneticists working on the study of the ice man. The scientists went to Red Hill, where Wang Binghua excavated, to exhume mummies reburied due to lack of space in the Urumk Museum. Analysis of the DNA samples confirmed that the mummies were Caucasoids, after which Mayr said that most likely the oldest mummies were representatives of the first white settlers in the Tarim River basin.

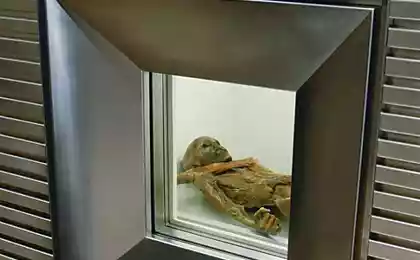

The oldest mummy found in Western China was nicknamed Loulan Beauty: this well-preserved body was found by Chinese archaeologists in 1980 near the ancient city of Loulan, in the northeastern part of the Takla Makan desert. A woman 5 feet 2 inches tall, who died at the age of 40 about 4,800 years ago, had features characteristic of the Caucasian race (including a protruding nose, high cheekbones, light brown hair that was collected and hidden under a felt headdress).

The body was wrapped in a wool shroud, leather boots on its feet, and next to it in the tomb lay a comb and an elegant straw basket with wheat grains. The next expedition to Loulan region, organized in 2003 by the Archaeological Institute of Xinyang Province, made a number of important new discoveries. The excavations were carried out 110 feet from the ancient city of Loulan, in a burial ground that was a 25-foot-tall mound of sand. Not far from the center of the mound, a rather interesting find was discovered - another stunning female mummy.

She lay in a coffin shaped like a boat wrapped in a wool blanket, in a felt cap on her head and leather shoes on her legs. Near the body were: painted red face mask, bracelet jade stone, leather bag, wool loincloth and ephedra sticks. Ephedra is a medicinal plant, shrub, used by the inhabitants of Iran in Zoroastrian rituals. Therefore, there may be some connection between these regions.

Later in the basin of the Tarim river managed to find another group of mummies - the bodies of a man, three women and a child - called Cherch mummies. Four adult bodies date back to 1000 BC. Their clothes were made in the same tones, and red or blue cords were tied around their heads, apparently indicating close kinship. The man from the burial, or Cherch man, more than 6 feet tall, died at the age of 50. He had long, light brown, braided hair, a thin beard and many tattoos on his face.

He wore a purple-red robe, and next to him lay at least 10 headgear of various styles. Like the Cherch man, one of the female mummies had many tattoos on his face. The 6ft-tall woman with light brown hair braided in two long braids was dressed in a red dress and white deer leather boots.

With adults buried three-month-old child with a blue felt cap on his head, whose eyes were covered with blue stones. Near the baby’s body was a bowl of cow horn and a feeding bottle made from the udder of a sheep. The family died of an epidemic.

Most of all, archaeologists were struck by the amazing preservation, brightness of colors and European type of clothing on these people. Dr. Elizabeth Barber, a professor of linguistics and archaeology at Western College in Los Angeles, conducted a detailed study of textiles found in the Tarim River basin and found striking similarities to the Celtic tartan used in northwestern Europe. The researcher put forward a version that the material found in the tombs of Tarim mummies and European tartan have a common origin. According to existing evidence, it appeared in the Caucasus Mountains at least 5,000 years ago.

Among the numerous garments, 15 graves of Chinese mummies were found: robes, caps, skirts, cloaks, tartan trousers and striped wool stockings. In the burial ground of Subishi, located in the northern part of the Silk Road, three female mummies were found, dating from 500-400 BC, in very high caps speckled, for which they were nicknamed the witches of Subishi.

Who were these Europeans and what were they doing in China? The range of finds is so wide, and their dating covers such a long period of time that the existence of one tribe is out of the question. They appear to be members of several groups of migrations that have moved eastward from various territories for thousands of years or more.

In some sources, there are mentions of residents of the Tarim River basin (the territory where the mummies were found), which may be the key to solving the origin of at least some of the mummies. In the Chinese sources of the first millennium BC. e. refers to a group of “white people with long hair”, who were called bai. They lived on China’s northwestern borders, and the Chinese apparently bought jade from them.

It is known that Yuezhi lived on this territory, which in 645 BC mentioned the Chinese author Guan Zhong. Yuezhi supplied the Chinese jade, which they mined in the nearby mountains of Yuzhi (Gansu province). After the devastating raids of nomadic tribes of the Huns, most of the Yuezhi moved to Transoxiana (a part of Central Asia covering the lands of modern Uzbekistan and southwestern Kazakhstan), and later to northern India, where they created the Kushan Empire. Portraits of Yuezhi kings on coins have led some researchers to the idea that they could be people of the Caucasian type.

Another people inhabiting these lands were the Tohars, Western tribes speaking Indo-European languages (a language group that includes most European, Indian and Iranian languages). Some scholars believe that the Yuezhi and Tohars are essentially the same tribes, called differently.

However, to date, this version has not been confirmed by the facts. The area in western China where the Caucasoid mummies were found, namely the northeastern part of the Tarim River basin and the lands located east of it near Lake Lobnor, correspond to the area of distribution of Tocharian languages in the future. Chinese sources say that the Tochars had blond or red hair and blue eyes, and frescoes of the IX century in Buddhist caves located in the basin of the Tarim River depict people with pronounced features of the Caucasoid race.

It is known that after the attack of the Huns, the Tohars did not leave the basin of the Tarim River, and later borrowed Buddhism from the population of North India. Tokharian culture existed at least until the eighth century, until they were assimilated with the Turkic tribes of Uighurs who came from the eastern Asian steppes.

Although no Tocharian texts have ever been found in the Tarim River basin with mummies, one place of residence and Tocharian drawings depicting people of the Caucasian race indicate with high probability that at least some mummified inhabitants of this region were ancestors of the Tocharians.

Did all these people cross Europe and half of Asia to settle in the arid desert of western China? Judging by the remains of textiles, the origin of which is associated with the Caucasian tartan from the south of Russia, and the data of linguistics, which indicate that the Indo-European languages originate in the same region, migration began from the region of the Caucasus Mountains in ancient times.

Dr. Elizabeth Barber hypothesized two waves of migration that began on the northwestern coast of the Black Sea, the supposed ancestral home of the Indo-European population. The first migration was the Western migration, which resulted in the emergence of the Celtic and other European civilizations. Another migration is associated with the ancestors of the Tocharians, who moved east to Central Asia and settled in the Tarim River basin. Thus, the Tarim mummified finds challenge the theory of the isolated development of Western and Eastern civilization.

B. Hawton.

Source: /users/1