147

How to stop being rude and start building strong social ties

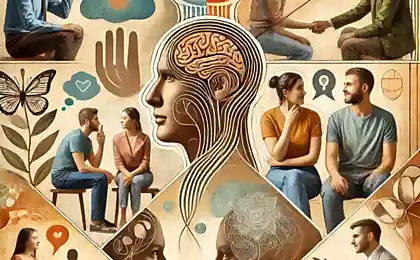

Invisible barriers to communication: why good people sometimes seem rude and how to fix it

Imagine a situation where you genuinely want to be a good person, but notice how people distance themselves from you after talking. Perhaps the problem is not your intentions, but the invisible communication barriers we unknowingly create. Modern communication psychology reveals amazing mechanisms of how our behavior affects the perception of others.

The Anatomy of Unconscious Brutality: When Good Intentions Turn Against Us

Roughness in the modern sense is not only direct aggression or outright rudeness. It is a complex social phenomenon involving nonverbal cues, subtle violations of personal boundaries and unconscious disregard for the emotional needs of the interlocutor. Research in social psychology shows that up to 70% of negative feelings about a person are formed not because of what they say, but because of how they do it.

Hidden signs of communication rudeness:

Monologic syndrome Turning dialogue into a one-way flow of information about yourself

Emotional blindness Inability to read nonverbal signals of discomfort

Temporary aggression Disrespect for someone else’s time and schedule

Boundaries of violation Ignoring personal space and privacy

The psychology of self-centered communication: why we become the main characters of other people's stories

One of the most common forms of unconscious rudeness is the capture of communication space. When a person constantly translates a conversation to himself, he unconsciously tells others: “My life is more important than yours, my experiences are more significant than yours.” Neuropsychological studies show that this behavior activates in the brain of the interlocutor the areas responsible for social rejection.

The Curious Explorer Technique

Before each conversation, ask yourself, “What amazing information can I learn from this person?” This simple mental attitude transforms your perception from “tell me about myself” to “learn about another.” The result is naturally arising questions and a sincere interest in the interlocutor.

The Architecture of Personal Boundaries: The Art of Respect for the Unseen

Personal boundaries are the invisible but real territory of the human psyche. Their violation is perceived on a subconscious level as aggression, even if it is committed for the best of intentions. Anthropological studies show that cultures with a high level of social trust are distinguished by a subtle understanding and respect for personal boundaries.

True politeness lies not in knowing the rules of etiquette, but in the ability to intuitively feel the limits of another person’s comfort and never violate them.

Practical strategies for respecting borders:

Preliminary consent technique: “Can I ask your opinion on...” instead of asking a direct question?

Emotional sensing method: Monitoring facial expressions to determine comfort levels

Progressive deepening strategy: Moving from superficial to more personal topics only when there is mutual interest

The Chemistry of Humor: When Laughter Becomes a Weapon

Humor is a powerful social tool that can both unite and divide people. Neurophysiological studies show that a bad joke activates the same centers in the brain as physical pain. Ironically and sarcastically, these forms of humor require a high level of trust.

The golden rules of safe humor:

Irony instead of ridicule: It is better to laugh at yourself than at others.

Situational humor: Jokes about what is happening around are safer than personal ones

Universality test: If you can tell a joke to a grandmother and a five-year-old, it’s safe.

The art of compliments: between flattery and sincerity

The right compliment is to acknowledge the efforts of man, not the givens of nature. Psychological research suggests that compliments about innate qualities can create discomfort, especially in a professional environment. An effective compliment is always specific, sincere, and concerns what a person has chosen or achieved consciously.

Advice as a gift or a burden: The psychology of unsolicited mentoring

One of the most subtle forms of communication rudeness is to give advice to those who have not asked for it. This behavior is subconsciously perceived as an assertion of intellectual superiority. Modern therapeutic practice shows that people are much more likely to need emotional support than practical solutions.

"Therapeutic question" technique

Instead of giving immediate advice, say, “Do you want me to just listen, or do you need options?” This simple question demonstrates respect for the autonomy of the individual and his right to determine for himself what kind of help he needs.

The Philosophy of Gratitude: The Transformative Power of Recognition

Gratitude is not just politeness, it is an acknowledgement of another person’s worth. Neuropsychological studies show that the regular expression of gratitude changes the structure of the brain, making us more empathic and socially attractive. It’s especially important to give thanks for what seems “taken for granted.”

Adaptive Communication: The Art of Social Chameleonism

The ability to adapt to different social contexts is not hypocrisy, but the highest form of social intelligence. Anthropological studies show that the most successful communicators intuitively feel the energy of the group and adapt to it, while maintaining authenticity.

Principles of social adaptation:

Observation before action: The first 5 minutes in a new group - time to study the dynamics

Energy mirroring: Correspondence to the pace and intensity of group communication

Flexibility in formality: Ability to switch between formal and informal style

Time as a currency of respect

In the modern world, time has become the most valuable resource. Disrespect for someone else’s time is perceived as one of the most serious forms of social rudeness. Studies show that chronic lateness can destroy relationships even more than open conflicts.

Emotional Regulation: From Reactivity to Mindfulness

The ability to control your emotional reactions is a key skill in mature communication. Neurobiological studies show that there is a critical gap of 6 seconds between the emergence of an emotion and our response to it - it is in this time window that we can choose a conscious response instead of an automatic response.

There is space between stimulus and response. In this space lies our freedom of choice. And on this choice depends our growth and happiness.

The Art of Apology: The Alchemy of Trust Restoration

The right apology is not just an admission of error, it is a demonstration of emotional maturity and willingness to change. Modern psychology identifies five components of an effective apology: acknowledging responsibility, expressing regret, demonstrating an understanding of the consequences, promising change, and asking for forgiveness.

The structure of the transformative apology:

1. Specificity: Sorry to interrupt you during the presentation.

2. Empathy: “I understand that this might have embarrassed you in front of your colleagues.”

3. Obligation: “Next time I’ll pause or write down my question.”

Conclusion: The Path to Authentic Charisma

True charisma comes not from a desire to impress, but from a genuine interest in others. When we stop being the center of our universe and begin to see value in each person, our communication naturally becomes warmer, more respectful and more engaging. These are not manipulation techniques, but the path to true humanity.

Remember, perfection in communication is unattainable, but the desire to understand and respect other people makes us better every day. Every conversation is an opportunity to create a bridge between two worlds, between two unique human experiences. And in this building of bridges lies the true magic of human communication.

Glossary of terms

Empathy. The ability to understand and share the emotional states of others, putting yourself in their place.

Nonverbal communication Transmission of information through gestures, facial expressions, posture, tone of voice and other non-verbal signals.

Personal boundaries The psychological and physical limits a person sets to protect their comfort and safety.

Social intelligence The ability to understand social situations, read emotional cues, and interact effectively with others.

Active hearing Communication technique, in which the listener is fully focused on the interlocutor, asks clarifying questions and demonstrates understanding.

Emotional regulation The ability to manage your emotional reactions and choose appropriate responses in different situations.

Communication barriers Obstacles to communication that interfere with the effective transmission and understanding of information between people.