197

Dunning-Kruger effect: Why does the knower underestimate himself and the ignorant overestimate himself?

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: The Paradox of Perceiving Your Own Ability

Icon of Saints Dunning and Kruger, protectors and patrons of all experts, gurus and authorities.

Have you ever noticed how beginners are often overwhelmed with enthusiasm and confidence, while real experts approach their field with caution and doubt? This phenomenon is not accidental - it has a scientific explanation, the name of which is the Dunning-Kruger effect. Discovered at the end of the twentieth century, this psychological paradox reveals a surprising pattern: the less a person knows, the more competent he considers himself, and vice versa.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with a low level of competence in a particular field tend to overestimate their abilities, while experts, on the contrary, underestimate their skills or overestimate the complexity of tasks for others.

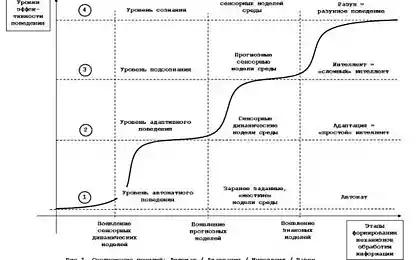

Visualizing the Dunning-Kruger Effect Curve: The Path from the Illusion of Competence to True Mastery

The story of discovery: how the bank robbery led to a scientific breakthrough

In 1995, MacArthur Wheeler, not the most prominent criminal, robbed two banks in Pittsburgh in broad daylight without making any attempt to hide his identity. When he was arrested that same evening - police easily identified him from surveillance footage - he was genuinely surprised. "But I smeared lemon juice!" he exclaimed.

Wheeler was convinced that the lemon juice used as invisible ink would make his face invisible to cameras. He even tested his theory by photographing himself with a Polaroid camera after applying the juice. The fact that his face was barely visible in the picture (probably due to improper use of the camera) only reinforced his misconception.

This story interested psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger from Cornell University. In 1999, they published their findings in a paper titled Inept and Unsuspecting: How Difficulty Recognizing Your Incompetence Leads to Higher Self-Esteem.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: An In-depth Analysis

Dunning-Kruger effect curve

In the early stages of mastering the skill, a person quickly reaches a “peak of self-confidence” or “mountains of stupidity.” With the accumulation of experience and knowledge, there is an awareness of the complexity of the field - the "valley of despair" comes. Further training leads to a gradual increase in confidence based on real competence, which is reflected in the plateau of stability and the subsequent slope of education.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is based on two key psychological phenomena:

- The double burden of incompetence People with low skills not only make bad decisions, but also lack the metacognitive abilities necessary to become aware of their mistakes.

- The curse of knowledge Experts often forget how difficult learning was for them and assume that others have similar basic knowledge and understanding.

A visual metaphor for “mountains of stupidity” – the first peak of self-confidence with minimal knowledge

Why do incompetent people overestimate themselves?

Studies show several reasons why people with low skills tend to have high self-esteem:

- Lack of understanding of standards of excellence in this field

- Inability to distinguish between your own work and high quality work

- The tendency to evaluate one’s abilities based on subjective feelings of effort rather than objective results

- Cognitive confirmation bias – the tendency to notice information that confirms existing beliefs

- Social mechanisms to support self-esteem and fear of admitting incompetence

Studies show that the Dunning-Kruger effect is not associated with intelligence or IQ. It manifests itself in people with any level of intelligence and refers more to metacognition - the ability to evaluate their own knowledge and skills. Even highly intelligent people can be exposed to this effect in areas in which they are not experts.

Why do experts underestimate themselves?

Highly skilled professionals often show the opposite trend:

- Deep understanding of the complexity of the subject and all the nuances to consider

- Awareness of the boundaries of one’s own knowledge and the existence of “known unknowns”

- The tendency to compare yourself to other experts rather than to the average

- Assuming that tasks that seem simple to them are just as easy for others (cognitive projection error)

- Impostor Syndrome - Fear of being exposed as a 'fraudster' despite obvious achievements

This cognitive phenomenon penetrates into all spheres of human activity:

In a professional environment

Imagine the situation: in an interview, an inexperienced candidate exudes confidence and promises to solve all the problems of the company, while a truly qualified specialist honestly admits the limitations of his knowledge. Who is more likely to be chosen by an untrained interviewer? Such mechanisms often distort staff selection, promotion and project allocation.

Practical recommendations for HR professionals

- Use standardized skills tests instead of self-assessment

- Pay attention to candidates who recognize gaps in their knowledge

- Conduct practical tasks that demonstrate real skills

- Ask for concrete examples from experience instead of abstract statements about competence.

Education and science

Students in the early stages of learning often overestimate their understanding of the material. A 2006 study at the University of Michigan found that students who scored the lowest on the exam overrated their score by 30%, while top students underestimated their achievement by 15%.

The scientific community is not immune to this effect: young researchers may be more categorical in their findings, while experienced scientists are more likely to use cautious formulations and point out the limitations of their research.

In politics and public debate

Political debate is particularly affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect. People with superficial knowledge of complex economic, social, or geopolitical issues often express the most radical and categorical opinions. A 2018 study published in the journal Political Psychology found that people least familiar with the geography of certain regions were most likely to support military interventions in those regions.

The Contrast Between Expert Caution and Novice Confidence in Complex Data Analysis

How to overcome the Dunning-Kruger effect?

Realizing the existence of this cognitive distortion is the first step to overcoming it. Here are practical strategies for dealing with this phenomenon:

Strategies for Personal Growth

- Cultivate intellectual humility Recognize the limits of your knowledge and be open to criticism

- Practice metacognition Regularly analyze your own thought processes and the basis for your beliefs.

- Look for feedback. Especially from people with extensive experience in the field you are interested in.

- Ask questions. Curiosity and willingness to learn are the best defense against overconfidence

- Use the principle of “consider facts that contradict your opinion” It helps correct beliefs and reduces cognitive distortions

For managers and teachers

If you work with people and are responsible for their development, pay attention to the following approaches:

- Create a safe environment where acknowledging ignorance and error is not punished, but encouraged.

- Provide concrete and constructive feedback instead of general assessments

- Show examples of expert thinking and decision-making

- Use confidence calibration – teach people to express confidence in their responses as a percentage and compare those estimates to actual accuracy

Ask yourself, “How would I explain this concept to a child?” or “Would I be able to write a detailed essay on this topic now without additional sources?” If you find it difficult to put a topic in plain language, it may indicate that there are gaps in your understanding, despite a subjective sense of competence.

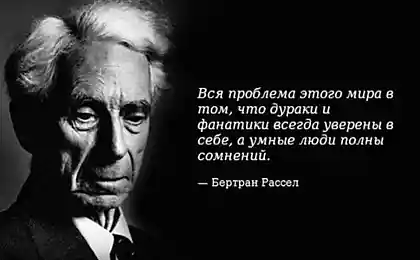

“Real wisdom consists in knowing that you know nothing.” - Socrates. This quote, uttered more than 2,400 years ago, surprisingly accurately describes the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Conclusion: Balance between Confidence and Humility

The Dunning-Kruger effect reveals the paradoxical nature of human cognition: not only do we not know many things, we often do not realize the extent of our ignorance. This phenomenon demonstrates why epistemic modesty—a quality that real experts often possess—is a sign of intellectual maturity.

The optimal approach is to find a balance between the healthy confidence required for action and achievement and the intellectual humility that leaves room for constant learning and adjustment of one’s perceptions. Awareness of the Dunning-Kruger effect in one’s own life is the first step towards a more objective assessment of one’s abilities and more effective learning.

Ultimately, understanding this psychological phenomenon helps us to become not only more competent, but also wiser, reminiscent of an ancient truth: the more we know, the more clearly we realize how much remains to be learned.

Glossary of terms

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

Cognitive bias, in which people with a low level of competence in a particular field overestimate their abilities, and experts, on the contrary, tend to underestimate their level of skill or overestimate the complexity of tasks for others.

Metacognition (metacognition)

Thinking is the ability to analyze one’s own cognitive processes, to realize the limits of one’s knowledge and understanding. Includes skills in planning, monitoring and evaluating your own learning and thought processes.

Cognitive Distortion of Confirmation

The tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms existing beliefs or hypotheses while ignoring conflicting data.

Impostor syndrome

A psychological phenomenon in which a person is unable to recognize their achievements and experiences a constant fear of being exposed as a “fraudster”, despite obvious evidence of competence.

Calibration of confidence

The ability to accurately relate subjective confidence in the correctness of judgments with their actual accuracy. A well-calibrated person is 90% sure of only those judgments that are true about 90% of the time.

Epistemic modesty

The intellectual virtue of being aware of the limitations of one’s knowledge and of the willingness to revise one’s beliefs in the light of new data. It is characterized by openness, openness to criticism and willingness to learn.

9 Academician Amosov Tips: A Path to Health and Longevity

Song designed to make it easier to fall asleep: "Weightless" by Marconi Union