190

Bach's Fugi: Music that awakens the brain

If you want to stimulate the mind, turn on Bach.

In the world of classical music, Johann Sebastian Bach holds a special place. His fugues are not only the pinnacle of musical art, but also a powerful brain stimulation tool. Scientific research in recent decades shows that complex polyphonic works, such as Bach's fugues, activate many areas of the brain, improving memory, attention and emotional state. This article dives into the amazing world of the intersection of music and neuroscience, revealing how Bach's fugues can become a workout for your mind.

Imagine sitting in a cozy room listening to the intricate interweaving of Fugue melodies in C minor (BWV 847) from The Well-Tempered Clavier. Your brain comes alive, your neurons synchronize with rhythms and harmonies, creating a real symphony of activity.

What are fugues?

Fugue is a complex musical form in which multiple melodic lines, or "voices," interact to develop one basic theme: the subject. Each voice comes in successively, intertwining with the others, creating a rich and layered musical fabric. Bach fugi, such as those in the Well-Tempered Clavier, are distinguished by mathematical precision and emotional depth. For example, Fugue in A-flat major (BWV 862) demonstrates how Bach masterfully combines logic and feeling.

This complexity is not only mesmerizing, it also forces the brain to actively work by processing multiple melodies at once, which research shows improves cognitive function.

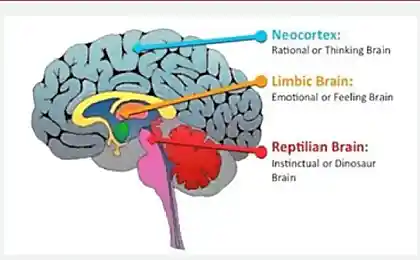

How does music affect the brain?

Music is one of the most powerful stimulants of the brain, involving several of its areas at once: the auditory cortex, the hippocampus (memory), the amygdala (emotions), the motor cortex and the reward system that secretes dopamine. According to Harvard Medical School, music stimulates emotions, memory, and even motor function, even if you’re just listening. Bach fugi, due to their polyphonic structure, are particularly effective for such multifaceted exposure.

Interestingly, even when listening passively, music activates the motor cortex, as noted by the iMotions Neuroscience Blog. This explains why, listening to the rhythmic Orchestra Suite No. 2 in B minor, Badineri (BWV 1067), you want to move or tap your foot.

Why are Bach's fugues special?

The complexity of Bach fugues makes them a unique tool for brain stimulation. A study by Zatorre et al. (1998) showed that polyphonic music activates the right temporal and frontal regions of the brain associated with spatial thinking and working memory. This confirms that fugues such as Fugue in C minor (BWV 847) require the brain to work hard.

Another study by Dean and Bailes (2015) found that major fugues, such as those in the Well-Tempered Clavier, are associated with joy and energy, while minor fugues are associated with melancholy. This demonstrates how Bach, through music, “talks” to our brains in the language of emotion.

Performing fugues such as Fugue in A-flat major (BWV 862) further enhances cognitive benefits. As the music blogger notes, playing fugues stimulates neurotransmitters, helping in cognitive development and recovery from injuries.

Neuroplasticity and music

Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to rebuild itself, forming new neural connections. Music that requires auditory, motor and cognitive skills is ideal for enhancing it. A 2024 review from the National Institutes of Health highlights that music contributes to the adaptive reorganization of brain networks, which may be useful for recovery from injury or neurodegenerative diseases.

Interestingly, Bach's music is even used to stimulate the brain in infants. The study, cited in Karen Pape, MD, shows that repetitive sequences, such as Jesus, Human Joy (BWV 147), help develop the brain and support recovery in children with neurological problems.

The game against listening: increasing the effect

Listening to Bach's fugues already stimulates the brain, but playing them offers additional benefits by leveraging motor skills and a deep understanding of structure. As the music blogger notes, learning fugues like Fugue in C minor (BWV 847) improves memory, attention and analytical abilities.

Playing musical instruments is also associated with improved spatial thinking and language skills, making learning fugues particularly valuable.

Practical recommendations

How to use Bach fugues to stimulate the brain?

- Active listening: Listen carefully as you monitor different voices. Try, for example, to recognize the subject in Fugue in D minor (BWV 851).

- Regular activation: Make Bach's music a part of your day - while working, relaxing or traveling.

- Combination with tasks: Listen to Aria from Orchestra Suite No. 3 (BWV 1068) while reading or solving concentration problems.

- Learning the game: If possible, start learning fugues on an instrument. Even simple works, such as Fugue in C minor (BWV 847), will give a cognitive effect.

Conclusion: Symphony for the brain

Bach fugi are not only musical masterpieces, but also a powerful tool for training the brain. They activate thinking, improve memory, stimulate emotions and promote neuroplasticity. The story of Anna, a young pianist who, after a hand injury, returned to performing Fugue in A-flat major (BWV 862), shows how music can support recovery and cognitive growth.

Turn on Bach. Let your brain play in unison with genius.

Listen to a selection of Bach's works on YouTube.

List of Bach compositions from the video

BWV 147: Jesu, Joy of Man's DesiringBWV 147-Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068: II. Air on the G StringBWV 1068Metamorphose String Orchestra, Pavel LyubomudrovBach-Gounod - Ave Maria, CG 89a-Metamorphose String Orchestra, Pavel LyubomudrovCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: I. PréludeBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: II. AllemandeBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: III. CouranteBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007:IV. SarabandeBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: V. Menuett I — Menuett IIBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: VI. GigueBWV 1007Massimiliano MartinelliCantata BWV 156: Arioso (Arr. for Two Cellos)BWV 156Mr & Mrs CelloOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: I. Overture. LentamenteBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: II. RondeauBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: III. SarbandeBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: IV. BourréeBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: V. DoubleBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: VI. MinuettoBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas BlauOrchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067: VII. BadinerieBWV 1067Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina, Giuseppe Lanzetta, Andreas Blau

Glossary

Fugue

A musical composition in which one or more themes develop in several voices, harmoniously intertwining.

polyphony

Music with two or more independent melodic lines sounding simultaneously.

Neuroplasticity

The ability of the brain to form new neural connections for adaptation and learning.

PET (Positron emission tomography)

An imaging technique used to study functional processes in the body.

fMRI (Functional magnetic resonance imaging)

A technique to measure brain activity through changes in blood flow.

dopamine

A neurotransmitter associated with motivation, movement, and reward systems.

Why technology and comfort don’t make us happy

Leaflets Kiev: an effective way to express yourself in the capital