HOW to learn anything — 2 model of skill acquisition

Bashny.Net

Bashny.Net

The science of how to learn new things, could be one of the major applied disciplines of modernity. Each of us throughout life mastering many skills and abilities. No matter how different these skills are from making the cake and a Google search prior to the execution of Beethoven's sonatas and writing scientific articles — at their core lies a set of common principles. Understanding these principles would make the training more intuitive and painless process.

Psychology approaches to the formulation of these principles since its founding. Ebbinghaus curve, which shows the speed with which new material is forgotten, was opened in 1885 as one of the first such laws. Today we know the mechanisms of learning a lot more, though still not enough.

Model of skill acquisition will not only help to understand how the process of learning, but also to more effectively plan their own classes, to avoid unnecessary hardships and get the best result in less amount of time.However, they will not give you the most important — both regular and deliberate practice. This part of the work will have to be done yourself.

1. The main principles of teaching and training: how to learn anything in just 20 hours

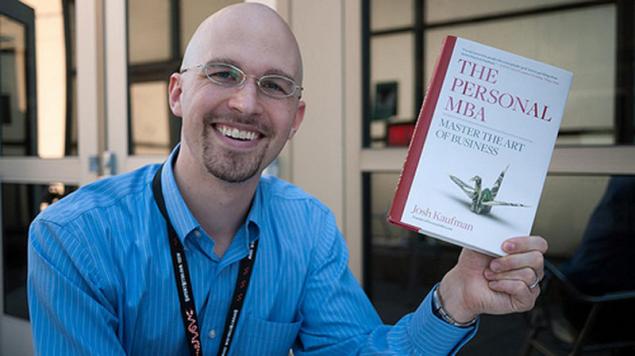

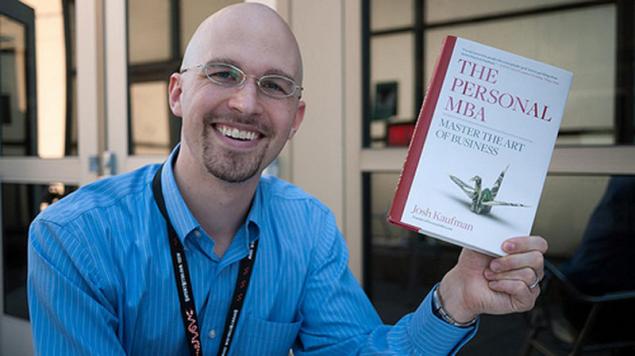

In his book "the First 20 hours", Josh Kaufman, bestselling author of "be your own MBA" offers a model of learning with which to master any skill in just 20 hours of concentrated practice. If you have to carve out hours and minutes in your schedule, and you want to leave time to rest, but also to learn something new, this model may be useful to you.

In acquiring any skill is possible to distinguish 4 main stages:

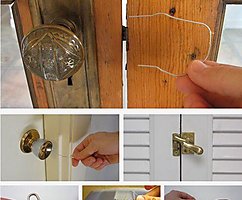

1. Break the skill into small elements.

2. Consistently study each of these elements;

3. To remove all obstacles and distractions, impeding learning;

4. Engage in regular exercise key elements of the skill.

If you want to learn to play the guitar, or yoga, is unlikely to immediately try to portray a jazz improvisation or to sit in the Lotus position. Start with a base position of the hands, acting out of simple scales and chords. Select the specific piece that you want to learn to play for the next 20 days and exercise every day for 1 hour. But first it is useful to become acquainted with literature: theoretical knowledge is important, because they allow you to purchase and fix our ideas about the practice.

These classes will not make you a musician but fun game you will be able to very soon — and maybe even take it to others. There is a belief that a good command of any skill requires many years of concentrated practice. What can you learn in 20 hours, if professionals gain the necessary experience your whole life? Indeed, to become an expert in some area, you will need much more time. Many studies conducted in various professional fields — from players and musicians to doctors and researchers show that these professionals are only after about 10 thousand hours of concentrated practice, and it is about 6 years of lessons and 5 hours a day. Yes and it is too favorable prognosis. What psychologist Anders Ericsson called "deliberate practice" (deliberate practice) requires a huge concentration of effort. Musicians, for example, can do really a conscious practice only about half a day. This format assumes that you are fully focused on what you are doing and get feedback from their actions — that is, unable to see what you do well and what is not. This is a hard thing to do.

In the book Kaufman there are two basic lists:

Here is the first, which describes the main principles of rapid skill acquisition:

1.Choose an attractive project.

2.Focus on any one skill.

3.Define the target skill level.

4.Break the skill into elements.

5.Prepare everything needed for training.

6.Remove obstacles to practice.

7.Highlight special time for practice.

8.Create fast feedback loops.

9.Engage in scheduled, short intense intervals.

10.Pay attention to quantity and speed.

Each of these principles may be crucial.Not selecting the desired level of skill or interesting for you project, you run the risk of aimlessly spend their time without learning anything specific. Without regular exercise you will be forced to go back to basics. Without feedback you will not be able to correct and improve their actions. And so on and so forth.

The second list is a list of principles of effective teaching, which also consists of 10 items. Training is different from practice, but it is no less important. Before proceeding to the actual practice, it is helpful to keep your efforts and to make a preliminary exploration. So you can learn how people coped with the same problems to you, save your time and give yourself less reason to give up in despair, when something will fail. Here is the list:

1. Learn the skill in question, and the associated region.

2. Admit that you don't understand.

3. Identify mental models and mental clues.

4. Imagine the opposite result desired.

5. Talk to the people doing it to know what to expect.

6. Eliminate from your environment all distractions.

7. To remember use spaced repetition and reinforcement.

8. Create support structures (i.e., templates used to build each lesson) and checklists.

9. Formulate and verify predictions.

10. Respect your body.

Mental models are ways to handle the problems that you face in any specific area. A scientist will think in terms of concepts, programmer — variables, and algorithms, the musician — music intervals, and music. Mastering any skill often requires the development of a whole separate language. Even if in this case you will not move beyond the level of a three year old child, it would be a great progress.

If you are already doing, practicing some skill, these principles are likely to be intuitive for you. But understanding only comes when you are faced with errors. This list need it in order to protect themselves from an excessive number of such errors, which ultimately can discourage any desire to learn.

Kaufman describes how two dozen of these principles make even the most, at first glance, difficult quite feasible:

"Just every day I had allocated about an hour for class favorites, but this was reasonable. Skills at first seemed an absolute mystery in a few days or even hours became clear. Each skill required little theoretical preparation, and about 20 hours of focused, deliberate practice" -from the book "the First 20 hours"

2. From novice to expert: six levels of skill

One of the most famous models of skill acquisition was developed in the early 1980-ies by brothers Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus of the University of California at Berkeley.

This model, first described in the article "Five-stage model of mental activities involved in the targeted acquisition of skills" and today is often found in scientific and popular literature.

The important thing is that it can provide is understanding the stage at which you currently are. Nurses was formerly only a tool for the realization of the decisions of the doctor. The Dreyfus model showed that the profession needed a greater level of autonomy. According to the augmented model Dreyfus, the acquisition of any skill is divided into six stages:

For advanced situational rule: in one situation one good, the other better to use more. Intermediate knows how to make not one cake, but several, and he would not prepare vanilla cake as well as chocolate. This is a good step in the direction of competence.

Competent sees not so much a rule, but rather their underlying principles and models. He begins to rely more on their own ideas and experience rather than a set of instructions. At this level you are more relaxed and have the flexibility to adapt to the situation. Here begins the area of personal responsibility for the outcome area, which many never reach.

Activities specialist to a lesser extent are based on principles and more on the sense of intuition. Specialist know how to act at the right time, and its choice is often correct. In place of many disparate parts begins to appear a single entity, "calculation and rational analysis as if melting before our eyes".

Expert in your field is even more intuitive: it just does — and it works. If it be asked why he took a decision, it can be difficult to formulate a response — it seems so obvious. And it is not arrogance, which is more common at the beginner level, namely a deep knowledge of the skill, mastered almost a reflex. This requires many days and months of practice: the experience of the expert "is so great that each specific situation immediately dictates to him on an intuitive level, the required actions".

The master is the expert who not only knows intuitively what and how to do it, but doing it in their own style. Each wizard features a deep personality. Until this point few people realize. Each master usually is a celebrity and a notable authority in your field. If you see the wizard, most likely, will understand it immediately: this man is completely immersed in his work.

I must say that the boundaries between these levels and moving between them there is no clear gradation. In addition, moving up the ladder does not always mean something good. For example, the expert is not always a good teacher, but a person who is at the previous stage, may feel in this role more comfortable.

The Dreyfus model was created based on the study of aviabiletov and players and is based on some philosophical premises-related phenomenology (one of the brothers Dreyfus later even became the author of a famous monograph on the works of Heidegger). Hence its most significant limitations: too much emphasis on intuition and too little meaningful improvement.

But intuition is not always deserves to be relied upon.As shown by the more recent work of psychologists-behaviorists — first and foremost, the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, author of the famous book "Think slowly... decide quickly" — intuition applies where there are stable rules and laws. It is important for doctors, chess players, or taxi drivers, but not for equity analysts. When the context becomes unpredictable, or too complex, it is better to abandon intuition and use clear algorithms. Alas, the human ability is not unlimited. Whatever experience you have, mistakes you still will have to make.

Two models of skill acquisition, which we have described in this material complement each other. Josh Kaufman has offered accessible and clear principles that simplify the training and make regular exercise more effective. If you keep handy this model, the rapid acquisition of a new skill will no longer seem so difficult and scary undertaking.

The Dreyfus model allows you to look at it from the other side. It will help to determine at what level of skill you are now and what you'll need for the next steps. Specific advice she gives, but tells potential prospects and knocks overconfidence. Before you can call yourself a competent specialist in any field, it would be useful to think about what this means. published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: newtonew.com/overview/two-models-of-skill-acquisition

Psychology approaches to the formulation of these principles since its founding. Ebbinghaus curve, which shows the speed with which new material is forgotten, was opened in 1885 as one of the first such laws. Today we know the mechanisms of learning a lot more, though still not enough.

Model of skill acquisition will not only help to understand how the process of learning, but also to more effectively plan their own classes, to avoid unnecessary hardships and get the best result in less amount of time.However, they will not give you the most important — both regular and deliberate practice. This part of the work will have to be done yourself.

1. The main principles of teaching and training: how to learn anything in just 20 hours

In his book "the First 20 hours", Josh Kaufman, bestselling author of "be your own MBA" offers a model of learning with which to master any skill in just 20 hours of concentrated practice. If you have to carve out hours and minutes in your schedule, and you want to leave time to rest, but also to learn something new, this model may be useful to you.

In acquiring any skill is possible to distinguish 4 main stages:

1. Break the skill into small elements.

2. Consistently study each of these elements;

3. To remove all obstacles and distractions, impeding learning;

4. Engage in regular exercise key elements of the skill.

If you want to learn to play the guitar, or yoga, is unlikely to immediately try to portray a jazz improvisation or to sit in the Lotus position. Start with a base position of the hands, acting out of simple scales and chords. Select the specific piece that you want to learn to play for the next 20 days and exercise every day for 1 hour. But first it is useful to become acquainted with literature: theoretical knowledge is important, because they allow you to purchase and fix our ideas about the practice.

These classes will not make you a musician but fun game you will be able to very soon — and maybe even take it to others. There is a belief that a good command of any skill requires many years of concentrated practice. What can you learn in 20 hours, if professionals gain the necessary experience your whole life? Indeed, to become an expert in some area, you will need much more time. Many studies conducted in various professional fields — from players and musicians to doctors and researchers show that these professionals are only after about 10 thousand hours of concentrated practice, and it is about 6 years of lessons and 5 hours a day. Yes and it is too favorable prognosis. What psychologist Anders Ericsson called "deliberate practice" (deliberate practice) requires a huge concentration of effort. Musicians, for example, can do really a conscious practice only about half a day. This format assumes that you are fully focused on what you are doing and get feedback from their actions — that is, unable to see what you do well and what is not. This is a hard thing to do.

In the book Kaufman there are two basic lists:

Here is the first, which describes the main principles of rapid skill acquisition:

1.Choose an attractive project.

2.Focus on any one skill.

3.Define the target skill level.

4.Break the skill into elements.

5.Prepare everything needed for training.

6.Remove obstacles to practice.

7.Highlight special time for practice.

8.Create fast feedback loops.

9.Engage in scheduled, short intense intervals.

10.Pay attention to quantity and speed.

Each of these principles may be crucial.Not selecting the desired level of skill or interesting for you project, you run the risk of aimlessly spend their time without learning anything specific. Without regular exercise you will be forced to go back to basics. Without feedback you will not be able to correct and improve their actions. And so on and so forth.

The second list is a list of principles of effective teaching, which also consists of 10 items. Training is different from practice, but it is no less important. Before proceeding to the actual practice, it is helpful to keep your efforts and to make a preliminary exploration. So you can learn how people coped with the same problems to you, save your time and give yourself less reason to give up in despair, when something will fail. Here is the list:

1. Learn the skill in question, and the associated region.

2. Admit that you don't understand.

3. Identify mental models and mental clues.

4. Imagine the opposite result desired.

5. Talk to the people doing it to know what to expect.

6. Eliminate from your environment all distractions.

7. To remember use spaced repetition and reinforcement.

8. Create support structures (i.e., templates used to build each lesson) and checklists.

9. Formulate and verify predictions.

10. Respect your body.

Mental models are ways to handle the problems that you face in any specific area. A scientist will think in terms of concepts, programmer — variables, and algorithms, the musician — music intervals, and music. Mastering any skill often requires the development of a whole separate language. Even if in this case you will not move beyond the level of a three year old child, it would be a great progress.

If you are already doing, practicing some skill, these principles are likely to be intuitive for you. But understanding only comes when you are faced with errors. This list need it in order to protect themselves from an excessive number of such errors, which ultimately can discourage any desire to learn.

Kaufman describes how two dozen of these principles make even the most, at first glance, difficult quite feasible:

"Just every day I had allocated about an hour for class favorites, but this was reasonable. Skills at first seemed an absolute mystery in a few days or even hours became clear. Each skill required little theoretical preparation, and about 20 hours of focused, deliberate practice" -from the book "the First 20 hours"

2. From novice to expert: six levels of skill

One of the most famous models of skill acquisition was developed in the early 1980-ies by brothers Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus of the University of California at Berkeley.

This model, first described in the article "Five-stage model of mental activities involved in the targeted acquisition of skills" and today is often found in scientific and popular literature.

The important thing is that it can provide is understanding the stage at which you currently are. Nurses was formerly only a tool for the realization of the decisions of the doctor. The Dreyfus model showed that the profession needed a greater level of autonomy. According to the augmented model Dreyfus, the acquisition of any skill is divided into six stages:

- Beginner

- Continuing

- Competent

- Specialist

- Expert

- Master

For advanced situational rule: in one situation one good, the other better to use more. Intermediate knows how to make not one cake, but several, and he would not prepare vanilla cake as well as chocolate. This is a good step in the direction of competence.

Competent sees not so much a rule, but rather their underlying principles and models. He begins to rely more on their own ideas and experience rather than a set of instructions. At this level you are more relaxed and have the flexibility to adapt to the situation. Here begins the area of personal responsibility for the outcome area, which many never reach.

Activities specialist to a lesser extent are based on principles and more on the sense of intuition. Specialist know how to act at the right time, and its choice is often correct. In place of many disparate parts begins to appear a single entity, "calculation and rational analysis as if melting before our eyes".

Expert in your field is even more intuitive: it just does — and it works. If it be asked why he took a decision, it can be difficult to formulate a response — it seems so obvious. And it is not arrogance, which is more common at the beginner level, namely a deep knowledge of the skill, mastered almost a reflex. This requires many days and months of practice: the experience of the expert "is so great that each specific situation immediately dictates to him on an intuitive level, the required actions".

The master is the expert who not only knows intuitively what and how to do it, but doing it in their own style. Each wizard features a deep personality. Until this point few people realize. Each master usually is a celebrity and a notable authority in your field. If you see the wizard, most likely, will understand it immediately: this man is completely immersed in his work.

I must say that the boundaries between these levels and moving between them there is no clear gradation. In addition, moving up the ladder does not always mean something good. For example, the expert is not always a good teacher, but a person who is at the previous stage, may feel in this role more comfortable.

The Dreyfus model was created based on the study of aviabiletov and players and is based on some philosophical premises-related phenomenology (one of the brothers Dreyfus later even became the author of a famous monograph on the works of Heidegger). Hence its most significant limitations: too much emphasis on intuition and too little meaningful improvement.

But intuition is not always deserves to be relied upon.As shown by the more recent work of psychologists-behaviorists — first and foremost, the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, author of the famous book "Think slowly... decide quickly" — intuition applies where there are stable rules and laws. It is important for doctors, chess players, or taxi drivers, but not for equity analysts. When the context becomes unpredictable, or too complex, it is better to abandon intuition and use clear algorithms. Alas, the human ability is not unlimited. Whatever experience you have, mistakes you still will have to make.

Two models of skill acquisition, which we have described in this material complement each other. Josh Kaufman has offered accessible and clear principles that simplify the training and make regular exercise more effective. If you keep handy this model, the rapid acquisition of a new skill will no longer seem so difficult and scary undertaking.

The Dreyfus model allows you to look at it from the other side. It will help to determine at what level of skill you are now and what you'll need for the next steps. Specific advice she gives, but tells potential prospects and knocks overconfidence. Before you can call yourself a competent specialist in any field, it would be useful to think about what this means. published

Author: Oleg Bocharnikov

P. S. And remember, only by changing their consumption — together we change the world! ©

Source: newtonew.com/overview/two-models-of-skill-acquisition

Tags

See also

How to learn to behave the way you would like to

How to teach a child to count

TATIANA CHERNIGOV "BRAIN LEARNING HOW TO TEACH"

How to teach a parrot to talk

How to learn to get up alarm clock

How to learn to get up early

The secret of studying anything from the genius of Einstein ... As I had not thought of this before ?!

How to learn how to catch up?

How to learn how to quarrel

How to teach children Thanks